I am coming to the end of the Glasgow Uni Creative Writing Society’s ‘Flash Fiction February’ Challenge. The aim is to write one piece of flash fiction a day, following prompts that are posted on the blog. The best thing I have probably achieved since I wrote my 10,000 word ‘The Quest’ story (complete with self-made Photoshop image and realistic fire effects) aged eleven is successfully averaging at least 700 words a day for a whole month (some days writing 700, other days moving upwards of 1300…). The reward is not just having a little portfolio of stories to go back and edit in the summer, but the habit of discipline that’s been earned. I have learned that I need the motivation of ‘completing something’, and that sharing one’s work and discussing it with others helps to feel better about writing. There is also the satisfaction of word count. If I averaged at least 700 a day, then that’s at least 19,600 for all of February. If I doubled my word count and did that for two months, I’d have a respectable 80,000 word novel. It’s an encouraging fact. Even if the content is sometimes pretty crap, I have something to work with! I just have to keep up the daily habit. It’s a bit like crack, only not so addictive, and cheaper. And, well, you have to work for its effects.

One of my fascinations is with the daily routines of successful writers. Not necessarily just literary authors, but philosophers, artists, journalists – even mathematicians. Anyone who gives up a significant chunk of their day to solitary writing, creating or just working. There is a fabulous blog called ‘Daily Routines’ which is the ultimate procrastination: putting off work by reading about how others work. It’s refreshing to see that not everyone needs a wee dram or French cocktail to get the imagination flowing, though it seems to be a recurring theme. As well as the time of day and the choice of stimulant, I’m a little bit obsessed with peoples’ medium: the effects of the pen, pencil or keyboard; how one’s writing implement impacts upon their style, speed and even argument.

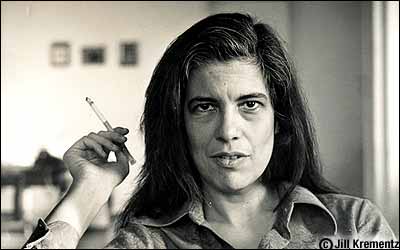

For instance, Susan Sontag on her writing routine:

I write with a felt-tip pen, or sometimes a pencil, on yellow or white legal pads, that fetish of American writers. I like the slowness of writing by hand. Then I type it up and scrawl all over that. And keep on retyping it, each time making corrections both by hand and directly on the typewriter, until I don’t see how to make it any better. Up to five years ago, that was it. Since then there is a computer in my life. After the second or third draft it goes into the computer, so I don’t retype the whole manuscript anymore, but continue to revise by hand on a succession of hard-copy drafts from the computer.

[…]

I write in spurts. I write when I have to because the pressure builds up and I feel enough confidence that something has matured in my head and I can write it down. But once something is really under way, I don’t want to do anything else. I don’t go out, much of the time I forget to eat, I sleep very little. It’s a very undisciplined way of working and makes me not very prolific. But I’m too interested in many other things.

One day I want to write a big essay looking at how writing style changes according to how you get the words on the page (I even bought a beautiful typewriter to test that out). I love the idea that Sontag uses layers and layers in her writing and editing: the process of writing on top of writing, of scrawling and scoring out like the palimpsest diary Cathy in Wuthering Heights creates on the margins of a bible. Like Heidegger with his under-erasure being.

I also find it fascinating how people can study and write with music playing around them. I used to be a lover of total silence: a pure space in which I find the need to fill up the void with words. Now I can sometimes do with a bit of ambient sound: coffee shop clattering, birdsong, falling rain and so on. It makes a difference whether you are in the actual space (writing in a real garden or a coffee shop, for instance) or in the hyperreal zone of generated sounds (there are excellent Youtube sources of ambient sound, from whale-song to fire crackling in a grate). One will distract me to write about immediate details, the other soothes you into a weird creative ‘roll’ where you can pour out your words or nonsense like code streaming out in hyperspace. OK, I’m being self-indulgent.

And indeed, there is a self-indulgent aestheticisim to all of this: the endless procrastination involved in selecting the correct font for a piece, the need to rearrange one’s desk or shuffle books or change your pen or whatever it is. Yet there is something more important here that relates to publishing itself and the way literature often gets sucked into a commercial vacuum (think of the likes of the Brownings’ letters or Shakespeare’s sonnets which get beautifully repackaged in time for Valentine’s Day) . The original text is beautified by the paratext, and what is left is perhaps more of a consumer object than a discourse of words and sentences. There is an emphasis on white space, the chic luxury of thick paper and the gaps between printed letters. James Fenton said that, ‘what happened to poetry in the twentieth century was that it began to be written for the page’. But what is this page? Is it the sublime landscape of print paper stretching out its possibilities of unblemished whiteness? Or perhaps the virtual page: the ever-changing Internet archive that risks the dreaded 404, this page is missing; that risks alteration and collaboration and manipulation – and is this not a good thing? It is poetry changing, in transition; undergoing the morphological process of the human into cyborg. An automated computer voice reading aloud, staggering over the dashes and tildas and sharps, the onomatopoeia and enjambment like a child having a crack at reading Derrida. Il n’ya pas hors text: there is nothing outside the text/there is no outside-text (he writes in Of Grammatology). When somebody reads aloud I imagine the words before me, drawing out of the page like butterflies coming to life; I can’t help it, it’s the way I learned to play with poetry. The world I like is the enclosed, shy space between the black ink and the reader’s eyes, the moving lips so silent.

Like the ‘fluttering stranger’ that Coleridge observes as a child at school in ‘Frost at Midnight’, words in poetry become strange: there is an uneasiness to them that we cannot quite place. Verbs, adjectives and nouns are not what our teachers told us. You cannot fix them to a blackboard, and anyway chalk crumbles. While butterflies might be pinned down and classified by their colours, words are dependent on each other for meaning. So signification sifts in swirls of dreamy reading, and the mind makes connections. The imagination stirs and sometimes forgets them. Footnotes adorn the margins and confuse us, as they perhaps do in Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, where we are driven into warmer but often more perplexing territory, as Coleridge’s gloss is less an academic explanation, and more a multiplicity of voices. At once, he joins in the action, ‘Like vessel, like crew!’ – yes, ‘her skin was white as leprosy’ – and we too catch this virus, moving between microbes of words that open and mutate through the strangest imagery. We shift between and through things with Coleridge’s metonymy, as in the gloss: ‘[a]nd its ribs are seen as bars on the face of the setting sun’. What are we to make of this being, ‘a Death’: an embodied spirit whose translucency both stirs and disturbs and amuses us, all at once? Aesthetics and meaning all blur into one.

With Romanticism what we often get is the journey, the progression through space, selves and substance, and through visual experiences: the sublime, picturesque and the beautiful. Not to mention the ugliness of Frankenstein’s monster, mirrored in Mary Shelley’s own monstrously patchworked collation of tropes and terrors and texts (imagine being raised on Milton but growing up like Rousseau – being both Satan and a noble savage – now that is Otherness embodied, surely?). We follow Wordsworth up Snowdon and along the Alps in his glorious Prelude, with the seamless switch between interior musings and the expansive, golden panoramic shot that reveals the gaping ice and mountains, the tracks the subject’s wandering thinness:

The unfettered clouds and region of the heavens,

Tumult and peace, the darkness and the light,

Were all like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree,

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of eternity,

Of first, and last, and midst, and without end.

(Wordsworth, Book VI of The Thirteen-book Prelude, lines 566-572).

Where nature itself merges into one terrifying being, where opposites uncannily forgo their differences to become ‘features | of the same face’ and still the sweet ‘blossoms upon one tree’, we are in a sublime landscape, and then in the pastoral garden. The subject stamps himself upon the mountains, as the mountains are stamped upon him; we recall, with the help of the OED, the varied meanings of the term ‘character’: as both noun (a literary figure of self/person; a sign or symbol used in writing, print, computing; a code; the properties of a substance) and verb (‘to distinguish by particular marks, signs, or features’). Wordsworth’s figure is the self encoded in the text, the lonesome Romantic imprinted in his white sublime of Snowdon, going deep into the very properties of the rock itself. All is viscous, melting subject into object. All is, as Timothy Morton so aptly puts it, a mesh: where there can be nothing ‘out there’, as we are all a set of strangenesses, part of an existence that is always coexistence; and yet we are not simply part of a holistic collective, but connected in our differences, in our mutations that separate, stick and undo us. There are those clouds which seem ‘unfettered’ and yet even they cannot rise above the poet’s vision, the tacky link of aesthetic projection that takes nature from unified cliché to a space of wilderness in which things move between abstraction and reification, and humans move with them in the ambiguous space between – like those viruses that multiply and mutate, ‘first, and last, and midst, and without end’.

This dangerous, homogenised idea of ‘landscape’ can be undone by thinking of it textually: as a palimpsest too of sorts, where human language adds layers to our understanding, alters our relationship with nonhuman things of the living and non-living. In writing and reading ‘nature poetry’, we are reconfiguring our place in the mesh; just as a drop of colour upon a single Paint pixel shifts the impression of the whole picture.

While Romanticism takes us on these messy forays into psyches and space, in the twentieth century we have, as Fenton has suggested, the poem as object: the poem as visual play on the page. The attempt to make the poem an object, to get to the very basics of objects. Think of Ezra Pound’s Imagism: ‘The apparition of these faces in a crowd; | Petals on a wet, black bough’ (‘In a Station of the Metro’). Think of William Carlos Williams’s notorious modernist poem, ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’, in which Williams’s poetics bring the object into stark and colourful being, like an object being rendered on some kind of graphic design program. Assonance coats our visual impressions so that we can almost taste what we see, the wheelbarrow ‘glazed with rain’. On the page, the poem too is a spilling of rain, of long lines dripping into single words, of basic objects hardening, forming. The ‘red wheel | barrow’; the ‘white | chickens’.

There is also the lovely aestheticism of the fin de siècle: the beautiful margins and separation of art and text in the The Yellow Book, and of course Husymans’s jewel-encrusted tortoise, which eventually dies from the weight of its ridiculous embellishments. Does a text too collapse under the weight of its stylistic ornamentation? The fashion for minimalism perhaps gives way to this assumption, and yet what about the explosive textuality of Finnegans Wake, Gravity’s Rainbow; anything by Henry James, or for that matter, Angela Carter? Art for art’s sake is not a dip into vacuity, but is necessarily a political statement, a textual position, after all. An attempt to escape the shading blinds of ideology. You might write a dissertation on the politics of purple prose; you might float buoyantly along the clear river of Wikipedia readings.

And now I have lost my place in the forest and cannot find the light again. Birds tweet shrilly and their song is like stars tinkling and various shades of darkness hang in blue drapes from the bowers of pine trees. If I look around I see the jewel of every dew drop glisten and I know that it is twilight. I am looking for something particular: that silent speck of a presence; that which evades me every time I turn over each new leaf. Only I know that I cannot see, cannot see the gathering of these particles; the light is fading and soon the day will close its drapes.

These are just words after all, and who would cling to them?

Some further words:

Derrida, Jacques, 1967. Of Grammatology.

Edgar, Simon, ‘Landscape as Story’, Available at: http://www.lucentgroup.co.uk/the-landscape-as-story.html

Morton, Timothy, 2010. The Ecological Thought.

Huysmans, J. K. 1884. À rebours.