The first song I was ever obsessed with was Suzanne Vega’s ‘Marlene on the Wall’. It was on a compilation CD called Simply Acoustic that I’d found somewhere in the house. I’d listen to it over and over again on the CD player in my room. What I loved about this song was its narrative possibility. The protagonist triangulates her love affairs under the watchful eye of ‘Marlene’ looking down at her from the wall. My child’s mind made up all kinds of stories about this. Marlene could be an older sister, a mentor, maybe the lover of one of the men that passed through the life of her. Marlene seemed cold. She was not a jealous lover, she didn’t act out. Anything advised by Marlene is provisional, ‘what she might have told me’. I imagined her having very thick eyeliner.

For a long while, Marlene was a kind of angel to me. I saw her wherever I saw people on the wall. A Picasso print of a woman drinking coffee on a balcony. I haven’t been able to source this painting except to remember there was long dark wavy hair, the colours purple and yellow, coffee. I remember thinking it looked a little like my mother. It’s not something we kept when we had to clear her flat this summer. Maybe I took a picture, but I don’t want to look for it. Marlene showed up in my dreams. Marlene was there in my imaginary stories. I could never tell if she was the protagonist of a life or someone to whom things were done. She seemed to encapsulate a distant sexual maturity while also representing ‘the impossible’ and so, the untouchable.

*

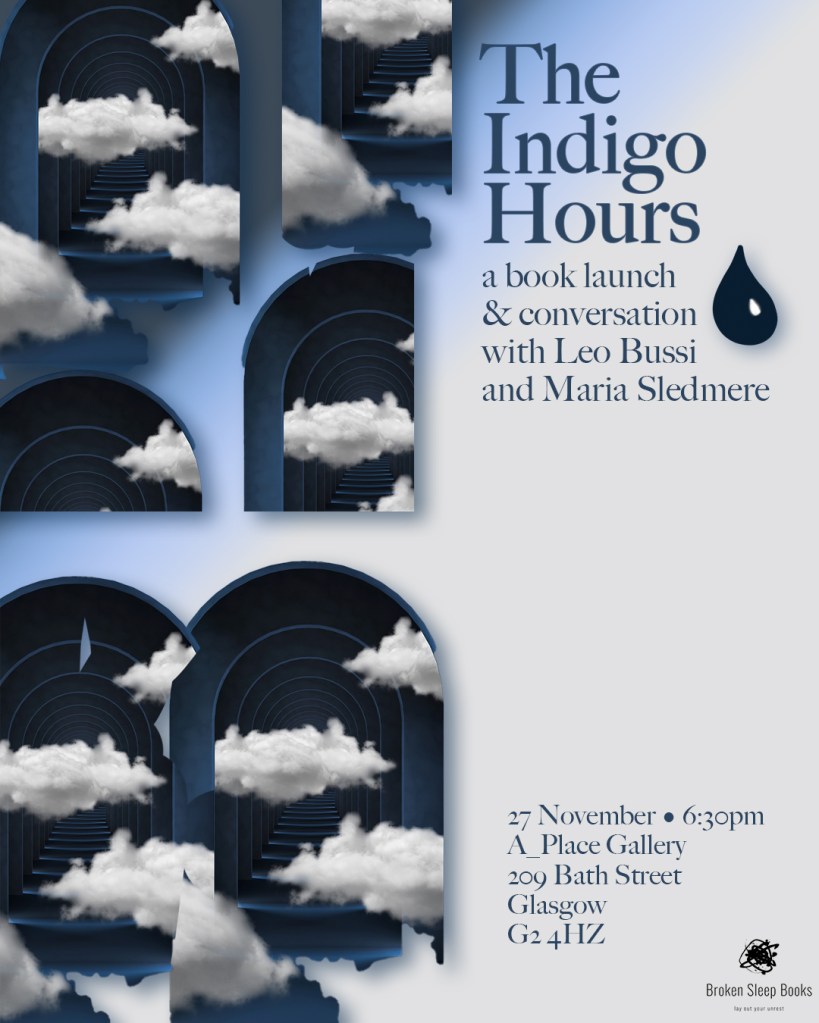

I see 2018 as an apex year in my life. I remember dazzling summer nights, two kingfishers, kissing in the midst of cinders, hiding, my phone pinging constantly, no homework, sparkle emoji. This was the year I wrote the novella that Broken Sleep are publishing next week. I started writing The Indigo Hours partly in solidarity with a close friend who was writing a novella for her Masters degree. I was a year out from my MLitt and waiting to start a PhD. I don’t think we shared any work in progress; we just swapped manuscripts when we’d got to the end. I don’t remember writing this book. I don’t remember if I wrote it on my phone, a library computer, the Chromebook in the restaurant I worked at. Maybe it bounced between these locales. Maybe the bouncing was painful. It involved data loss. When I meditated today the AI-generated female voice said ‘find a point in your breath and this will be your anchor’. The point in my breath is a ‘flashing’ spot in my chest. It is an anxiety motor. It cannot be my heart because it is too centred. But of course it is my heart. Sometimes I think I have a second smaller heart lodged in my sternum, where I used to get an ache from purging. This heart is blue, a mottled and gold-streaked blue, and it is rare like the blue version of the rose, my middle name. Semi-precious.

I wanted to tell this story about two people kissing illicitly in a garden, surrounded by white poppies and mystery. I wanted to write about the indigo hour of midsummer dawn, when you are up all night with someone, the breath before a comedown, before it’s all over. I wanted to write about a relationship that felt like that and whose dramaturgy was always the dawn. I wanted to write about something that was ending over and over again, and the ending wasn’t the point. There was a life and people drifted in and out of it. I wanted to write about arousal and attention, sentiment and giving up.

The summer before The Indigo Hours took shape, I was writing a thesis about the curatorial novel, about object-oriented ontology. I was interested in what Ben Lerner says about fiction staging encounters with other art forms. For that to be embodied and taking place in a credible present. I was interested in the refrain of unseasonable warmth that haunts his novel 10:04, the way the narrator might have these hotspots of medial feeling owing to places in New York City where he received such and such a text. I was reading a lot of books that take place in the disintegration of some kind of love affair — Joanna Walsh’s Break.up and Lydia Davis’ The End of the Story (also loaned by the novella-writing friend). I don’t remember the plots of these books at all but I see them essentially as ‘novels that walk around, receiving and metabolising messages’.

Turning to write myself, I wanted to create a fictional world in the aperture of indigo, the special hours of Scottish nights in June and July where it never really gets dark — there remains this blueish glow to the sky. I knew these hours to be indigo because I didn’t really know what indigo looked like, only that it was some kind of shade of blue and everyone seemed to disagree about how light or dark it was. A morning and eveningness, a not quite. More like a mineral or texture.

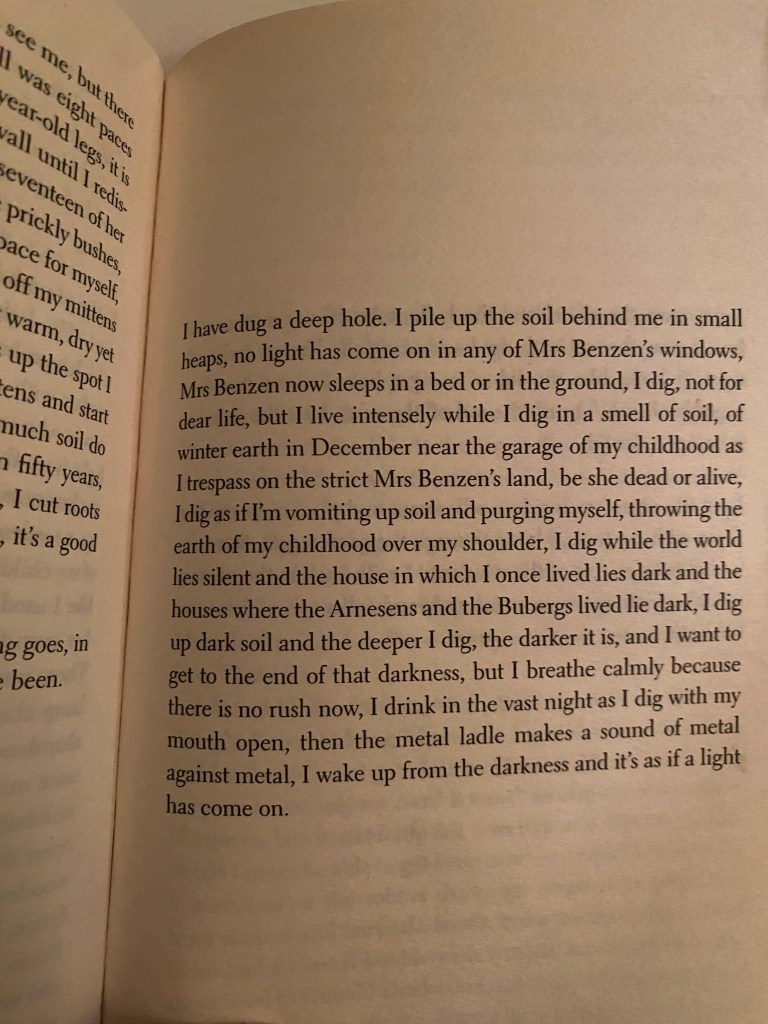

How deep in the woods to go to get this indigo. How deep in love did we go, or in druggy reverie. It all felt so subjective, translucent. The love I was writing about was already belated, collaged and distributed unevenly through various places, fantasies and timelines. What could I say about it? This love that made an ‘I’ into both subject and object. That distorted the closure we had been raised on to believe was love’s destiny. It was an ambient intimacy, then. It was in medias res, ongoing. The midtone of indigo. In the process of editing the raggedy manuscript (what I referred to, in an email to the poet Callie Gardner, as ‘the trashy wee thing’) a couple years later, I discovered the phenomenon of indigo children. Since then I have learned more about what it means to be an indigo from the writer Laynie Browne. I relate this to a phenomenon of emotional & intellectual hyper-attentiveness my ex and I used to refer to as ‘shine’, also to a feeling of hyper-empathy and sensitivity not just to the mood of a room but to the mood of anything more-than-human. If you are capable of shine, if you are inclined to indigo, your presence might follow a gradient opacity. In Committed: On Meaning and Madwomen, Suzanne Scanlon has a chapter ‘Melting’ which talks about what it feels like to have ‘no glue’ and no security: ‘You could melt into another person, or melt into a place like this [a psychiatric hospital]’. This melting is akin to what Stephen King calls ‘the shining’ or what others call ‘sensitivity, insecurity, shyness. Fragility’ (Scanlon). I’m interested in how to put that kind of melting character on the page. What would her voice sound like?

A vessel, a leaky container…a watercolour palette smudging ceaselessly in stroke after stroke…Being an indigo is a lonely experience but one that lights up at the world. Pure indigo has a high melting point; when heated, it will eventually decompose or sublimate. For some people, reading indigo must surely be excruciating. For others, it is true. I think indigos come from elsewhere, they remember other times, their memories mutate and take form in their dreams, they bear an awful gift, they don’t belong to any fixed thing. What could be their future, is it possible. It doesn’t have to be something that makes you special. There is a kind of love that makes you indigo, opens you. For a lot of my life and even now, I walk around like an animal or an open wound. These are cheap metaphors. It is more that I walk around like the weather. No, I walk around like indigo. I freeze-dry experiences into crystals and exhale them on the page. I can’t say whether this produces realism; it’s very smudged.

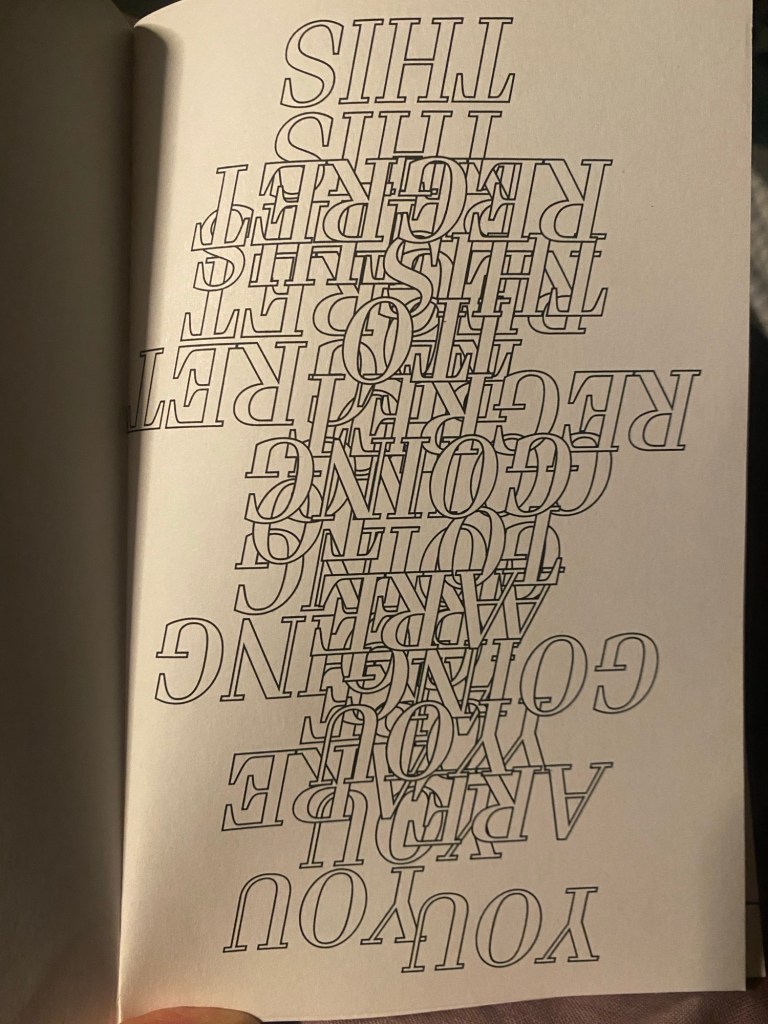

Trying to put Marlene on the page was an act of transmutation. I read Timothy Morton on beauty’s perception as an act of ‘attunement’. I wondered if my attempt at fiction was really just an attempt at sensing beauty. But there is a lot of horrible stuff in this book. A lot takes place in the shadows. A lot of the scenes are decontextualised and in a sense ‘free-floating’. We don’t get heightened climaxes and denouements so much as vignettes melting into one another. In Reading Machines: Ambient Writing and the Poetics of Atmospheric Media, Alec Mapes-Frances talks about the ambient poetics of Lisa Robertson and Tan Lin as a ‘vaporisation of the lyric subject or self’. I saw Marlene as a soluble force more than as a coherent character, a stable subject. Marlene was a problem to be solved; she was able to be dissolved. I needed the temporal mode of fiction to play this out over time, place and encounter. Ambience refers to the surroundings of something, the environment, a kind of base existence (there is light, it is blue; there is this mood; the room is cool) tinted with some accompaniment, encompassing. Can we plot ambience the way we might plot time? This was something I was concerned with when writing the book.

My friend Stuart read an early version of the manuscript and said something about it being constructed around several pillars or towers. I think he was referring to place, as it stands in the story. The central (unnamed) city, Berlin and the prairie. I imagined these towers as constructed of fragile pixels. A little data moshed and crumbling. The movement through the story might be closer to a dérive or distracted wandering (I imagine readers skipping over, revisiting, forging microloops as I did in the writing). Insofar as I can remember writing the book (which I cannot) I was doing so in order to ‘read’ a relationship. This took place in a series of loops and compressions. Similar things said, the same mistakes, rotations of closeness and distance. My towers were constructed to make something semi-permanent of a very dissolving time. Aaron Kent’s cover for the book invites you to choose from various alcoves and passageways, or drift onwards into mise-en-abyme. All the while, in the company of clouds. I recently rewatched season 2 of Twin Peaks and the finale, in which Agent Cooper slips in and out of red curtains while seeking Annie, or answers, resonates. Disorientation. Passing through thresholds. Trying to save your love from evil. And what if it was not one love, but a concatenation of shadows?

Evil was also the ravages of shame and depression, the doubling of seeing the dark in yourself. Or, depression was a particularly sensitivity to evil. I get into these loops about it. There is so much evil in the world. For much of my life, I have not felt like a person. There are clouds drifting in that part of my soul that is supposed to feel warm and full. “I am okay” etc. I am like a child, lily-padding over the clouds. The same child that needed Marlene to guide me. I experienced love as something annihilating and so bright. The blue-heart anchoring pain in my chest. Hawk tells Cooper that if you go into the Black Lodge ‘with imperfect courage, it will utterly annihilate your soul’. What does it mean to give your narrator courage? I wanted her to have the courage of suffering and to see that in others. To suffer what would never work out. A constellation of burst blood vessels around the eyes. To have the strength to look in them, for that look to be a holding place, then a continental shelf, then nothing.

A foothold, even. For someone climbing the tower, trying to get to the kissable moment again and again. For the tower to be a text. I go to the tower, I spiral in stairwells, I see a prairie stretching farther and farther, I get so thirsty.

*

Are such towers architectures of refuge or incarceration? Here’s a passage from Hélène Cixous’ Hyperdream, a novel about grief, love, friendships, telephones and mother-daughter relationships (I will never not be obsessed with):

We don’t stop killing ourselves. We die one another here and there my beloved and I, it’s an obsession, it’s an exorcism, it’s a feint, what we are feigning I have no idea is it a sin a maneuver a vaccination the taming of a python the fixing-up of the cage, it’s an inclination, we don’t stop rubbing up against our towers touching our lips to them

Haunting the novel is this allusion to 9/11, but the towers as totems seem also to be something else, much more imaginary: ‘I saw it shimmer in my thoughts’, Cixous says of her ‘dearly beloved originary tower’. In an early document for The Indigo Hours I had this epigraph I haven’t since been able to locate from Morton, something about beauty being a homeopathic dose of death. I see my love go out the wrong door, I see a certain look, a turning back. Towers of collapsing sand. I see Marlene on the wall. Marlene from a tower. Marlene as the mother-tower, no, the sister. All my life I have said, who is she? She whose name means ‘star of the sea’. I rap at the door of Montaigne’s library tower. It survived a fire.

The homeopathic dose of beauty, like Cixous’ vaccination, prepares us for exquisite loss (and so soaring, to tower over). In a way, The Indigo Hours quite simply plots the disintegration of a what is now called a situationship. But really it is a book about everything happening in one plane, each shifting tense another groove of growing older. Growing into the old you were before. Essaying through this experience via encounters with art — everything from installations to Lana Del Rey (on whose early albums the narrator delivers protracted sermons — this being a book loosely about finding meaning in the spiritual emptiness of the 2010s). No, it is a book about things and time and pleasure.

Only recently did I look up the meaning of the song ‘Marlene on the Wall’. Apparently Marlene was the German actress, Marlene Dietrich, whose heavy gaze looks down from a poster. Maybe this is why my protagonist so frequently visits Berlin. Vega talks about writing the song for Dietrich after turning on the TV one night, her ‘beautiful face in close-up’. ‘Marlene on the Wall’ is a coming-of-age song, it’s also about power and violence, beauty and changing. There’s a butchershop but also a rose tattoo. I saw the song as an eternal love story with destruction as its anchor point. ‘Even if I am in love with you’ being the parenthesis through which to begin the working backwards of what Joanna Walsh calls the ‘fresh and terrible’. If I carried around that song I also carried the ghost-image of Marlene’s televised face in monochrome. How alien those brows, the beauty of another time. When I read fiction, when I edit fiction, when I approach a story, so often my question is ‘so what?’ I am looking not for answers, but for experience. Fingerprints.

Vega’s opening: ‘Even if I am in love with you / All this to say, what’s it to you?’ could be the central premise of The Indigo Hours. So for this book to be ambient is to be deeply interested in the ‘it’. Of love, of the being-in, of melting into the world, being washed continuously in its blood, its indigo, its chlorinated swimming pools. To look for explanation is one of many reasons for fiction. If Marlene peeled off the wall, I saw her growing along some trellis as a rare blue flower, a wallflower but livid and shedding, changing. I would write to water her, I would coax my clouds for a little rain.

Blurbing The Indigo Hours, Amy Grandvoinet (brilliant critic of Surrealist & avant-garde psychogeographies) writes generously of ‘a languageful love pulsing constant’. A blue heart plucked and buried in the book, behind some cloudy curtain. This heart is sequined to the rhythm of life. If there is a cadence to the book it is love and love’s chaos sewn into patchwork. Marlene returns to Berlin to see her friend. She sees an old friend and cannot bear to reach him because there is this substance between them. She paraphrases T. S. Eliot’s ‘Burnt Norton’, she almost leaps the mirror fence. There are indigo seeds in these stories. I hope whoever reads it finds their own pulsing constant.

You can order the book from the publisher here. It is out on the 31st October.