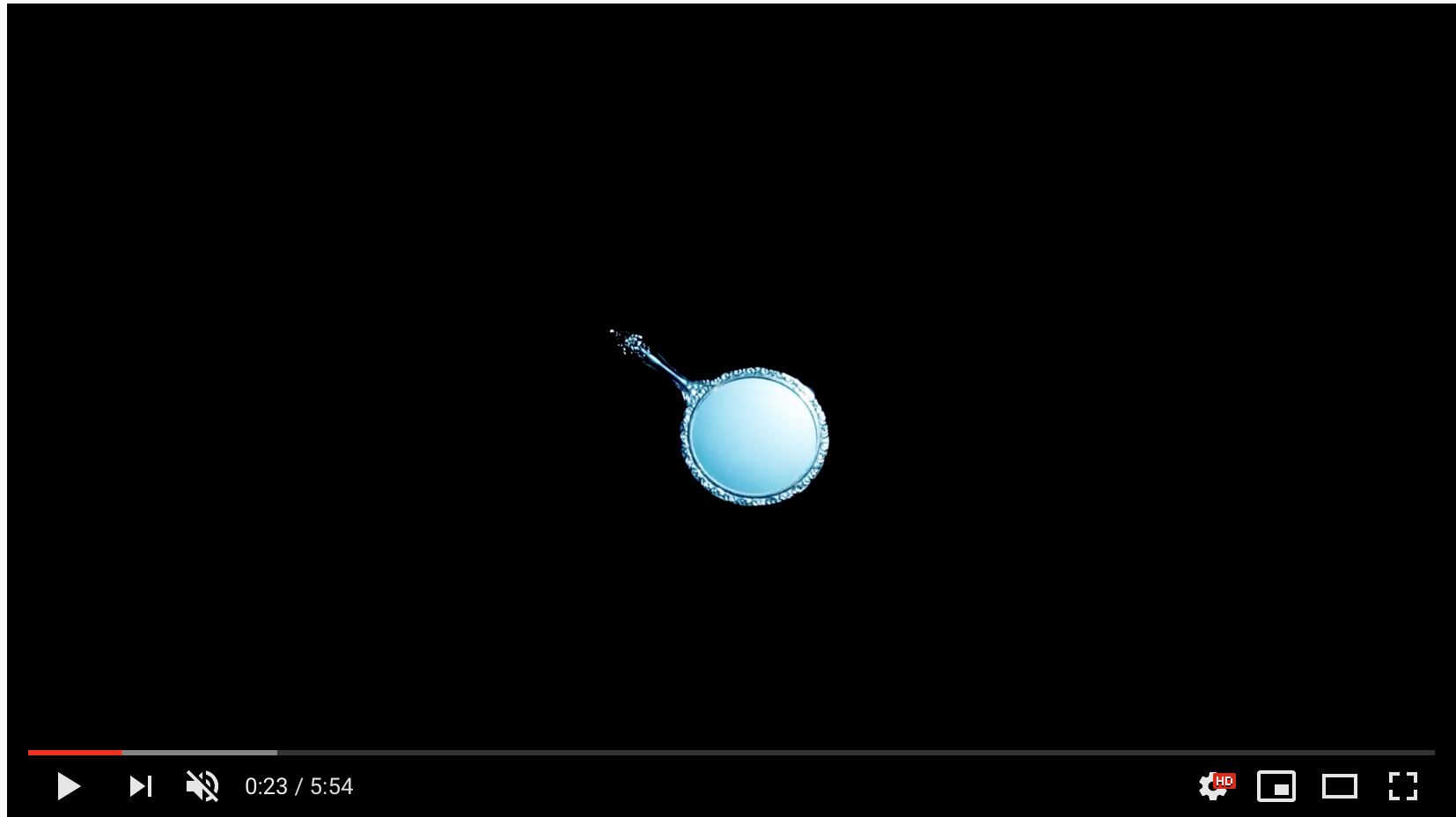

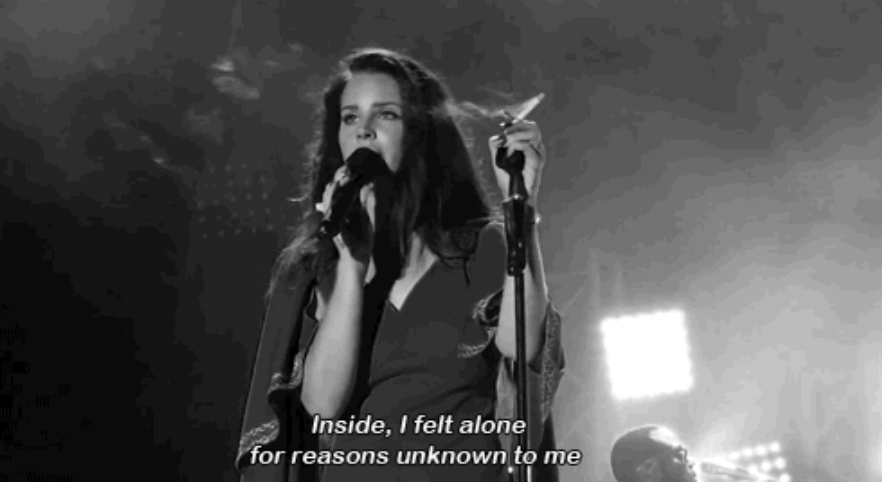

There is a scenario in which the jukebox is equivalent to the poet and some elaborate analogy is to be made between intertextuality and the limited catalogue whose selectional form produces play. The scenario only survives in video. It needs this urge of duration, not to mention the tenderness of a touch. Where fingers brush keys like notes, there is something to add to the story. A social space in demand of ambience; on flickering alongside off. When Lana is alone on stage, hands stuffed into a bomber jacket, singing ‘Fuck it, I love you’, swaying almost nervously, I want to think about what she is doing there and who she is speaking to and from where she is speaking. She is not really speaking but singing. The lone girl on the stage is the open mic dreamer, with nothing but lines. She is scattered across june-dreams of multiple personality: ‘The I which speaks out from only one place is simultaneously everyone’s everywhere; it’s the linguistic mother of rarity but is always also aggressively democratic’ (Riley 2000: 57-58). We mother our solipsism with words but in doing so there’s an opening. So to say fuck it and state the interruption with syncope, sincerity. Lana Del Rey was born on the cusp of Gemini and Cancer season, which more than explains that statement: ‘Fuck it, I love you’. With her sails to the wind. To say it over and smooth into plural refrain, you could even say chorus. For a chorus wants to be shared. It is a commodious mother, fed by the keys of the jukebox baby. There is a constant reversal of nourishing; the democracy of lyric utterance, the milky feed that streams.

Denise Riley argues that any ‘initial “I love you” is barely possible to enunciate without its implicit—however unwilled—claim for reciprocation’ (2000: 23). But what is reciprocation in a song? Is it just the urge to be sung with? And this ‘fuck it’, the pervasive millennial injunction to just be, to move on, as the tag which erases the expectant price of the utterance? Riley argues that I love you ‘must at once circulate as coinage within the relentless economy of utterance as exchange’ (2000: 24), but in a pop song it bears the leaden weight of so many prior expressions. The irony is that to cut through that with a simple fuck it, Lana can attain something like sincerity in the very pop mode whose lineage of commercialised love would surely undermine her feeling. Fuck it, in spite of saying I love you I really do. The pop song becomes this space for the staged epiphany of repeated assurance, I really do. It is a softcore admission of the self in its burning limit.

‘Fuck it I love you’ is soaked in lights, but they’re fading. ‘I like to see everything in neon’, is the line that opens the song. To see everything in neon is to fluoresce what is haunted and gone. I think of Sia dragging rainbow dust down her tearful cheeks in the video for ‘The Greatest’ — tragedy’s shimmer as fugitive mark on the body. Lana offers herself up as sugar dust, cliché in honour of Doris Day: ‘Dream a little dream of me / Make me into something sweet’; she acknowledges ‘dancing to a pop song’, but it’s not clear if this is her or the character or the one she loves. ‘Turn the radio on’ could be a reflection or an imperative. The reader is hailed between these positions of love and the loved and the effect is saturating, warm, delirious. Separation is that ‘it’, the spacing. In the video, we watch Lana painting and then suddenly she’s surfing with the aurora borealis in the background. She’s on a swing, her jean shorts caressed by the camera, she’s the sexualised pop icon again. She’s on a surfboard, green-screened, young. She’s choosing a shade of yellow from the palette, singing ‘Killing me slowly’. What is this ‘it’, killing her slowly:

I’ll return to the unknown part of myself and when I am born shall speak of “he” or “she.” For now, what sustains me is the “that” that is an “it.” To create a being out of oneself is very serious. I am creating myself. And walking in complete darkness in search of ourselves is what we do. It hurts. […] a thing is born that is. Is itself. It is hard as a dry stone. But the core is soft and alive, perishable, perilous it. Life of elementary matter.

(Lispector 2014: 39)

I want slyly to argue that this is a kind of anthropocene existentialism. Recognition of the self as this ‘hard’, ‘dry stone’ thing of geologic mattering, reflexive species. This is what it is to be ‘Human’ right now. And yet the agential spark within, the ‘core’ that is being alive in a world where we have deposited those sedimentary layers. Creating ourselves in the stone, often with the tarnish of the very products we chose and developed to beautify, excoriate and cleanse ourselves, to remain forever young. So there is this oscillating temporality at work between desired infinity and the trace of our fugitive place on earth. The very earth minerals that would ruin humanity, mine our bodies of endless labour. But to go back to the song, with its idea of a gradual dying. I want to call this something like anthropocene softcore: the unnamed presence of species being within Lispector’s slender novel from the early seventies, or the Mamas and the Papas brand of late-sixties ‘sunshine pop’ whose solarity derives from the perishability of that energy, utopian commons, cascade of flowers — that serotonin glow of selves in streams and streams.

Lana’s anthropocene poetics are not of the hardline, direct call to action. You would not say of her cultural presence, eco-warrior or nature goddess. You would not brand her Miss Anthropocene in a kind of demonic marketing gimmick. You would say most often she is a siren, per se, leisurely supplicating us towards death on the rocks. Desirous flow. This is anthropocene softcore. This is what it is to challenge the act of self-description itself, and in doing so questioning those generalisations that arise from the ‘we’ of humankind, not to mention the ‘I’ of pop’s delectable, mainstream lyric. Alchemically, Clarice Lispector and Lana make of these malleable pronouns the ‘perilous it’. The it, the feeling, the speaking self which is nothing much more than a bundle of affects, sensations, atoms. To be cast over and crested by the wave. Significant that ‘Fuck it I love you’ ends with the rising bubbles of this wave, the one that spills us through the fourth wall and into the studio. This song slams together pop’s saccharine mythos of California as dreamland, a late-summer song as the former was written, surely, for autumn. California: ‘it’s just a state of mind’. She could be talking about the self or the state, or the state of the self.

What happens next? The shot drifts over the cliffs, the coast, to a strip of palms and a distant view of the LA skyline. That shining love in the previous track is replaced by a minor key, a glimpse of the jukebox whose songs include The Eagles, Bon Iver, The National. Artists whose Americana is the melancholy of generations moved from political despair to something like the glitch of the times as a basic fact of intimacy. One of the Bon Iver songs shown in the video is ‘22 (OVER S∞∞N)’, and if that title was not rife with implicit apocalypse, what is, what is. A stammering into language, pitch-shifting the fragile space of utterance. There’s a spiritual glimpse to the sky and the infinite quality of the stars:

There I find you marked in constellation (two, two)

There isn’t ceiling in our garden

And then I draw an ear on you

So I can speak into the silence

It might be over soon (two, do, two, do, two)

(Bon Iver, ‘22 (OVER S∞∞N)’)

I don’t know what the maths is doing. I don’t want to know that the song ‘was inspired in part by Bon Iver mainman Justin Vernon’s unsuccessful attempt to find himself during a vacation’. I am however interested in the hubris within this term ‘vacation’ at all. Do we now live in a world where you can take ‘time out’? There is nothing of the world we know that could be switched off. There is no ‘away’ of complete erasure or original presence. Deconstruction caught up with our living. Vernon describing this song as a gesture towards what might end of his emptiness could just as easily be flipped: its relief is equal to a mortal sense of loss. The impending erasures. It ‘does’ or acts the accretional event of extinction that is speaking into the silence, to those who could not speak back.

Fragments and snatches: the neon green lining Lana’s eyes, the aurora borealis, the neon green palm in the club where she sings alone. A season by yourself. The love of the couple together surfing is cardboard, Hollywood. It is a trembling symbol. It is almost ridicule.

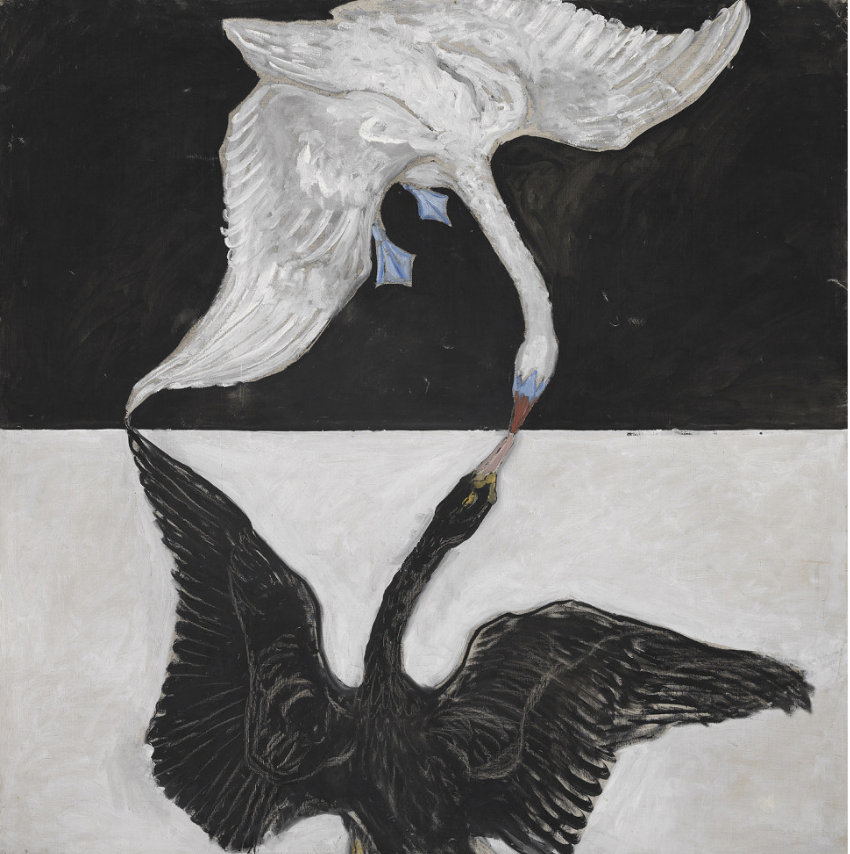

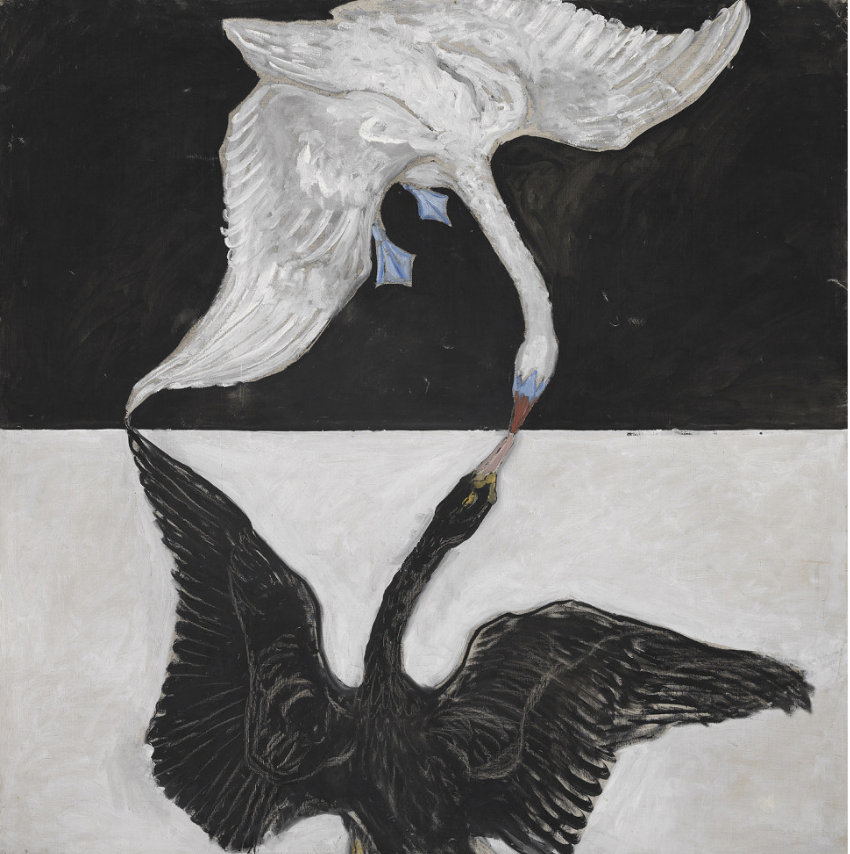

What is Justin Vernon looking for in the constellation? When he sings ‘two two’ I think of Hilma af Klint’s nose-touching swans, or the hours of the day chipped at the edge — two of them stolen by tragic event. I think of a mic check, two, two, ch, ch. Click. Near-enough-presence of speech. A white swan on black background; a black swan on white background. Flip. The swans are geometry, signets of signature, they move towards abstraction. Growth. I love them. Fuck it I love them. The way they are just it. Inversions of colour and a monochrome mood splashed with cornflower blue, the tiny excess we can treasure. It is the cornflower blue, the little webbed feet, which make the swan in question unique. So we can care for it, figuratively as it swells through grey-white waters of memory. The swans we have lost in our shit. Royal iterations freed from belonging. This painting is from af Klint’s series Paintings for the Temple, works derived from spiritual communication. The abstraction of the swan / renders us stark in frame / for we were Lana or Leda / before we were animal. Sufjan Stevens’ ‘Seven Swans’: ‘All of the trees were in light’, ‘a sign in the sky’; ‘My father burned into coal’. And all of our sadness was carbon neutral before this. We plunge into whatever remains of the water, its plasticky thickness.

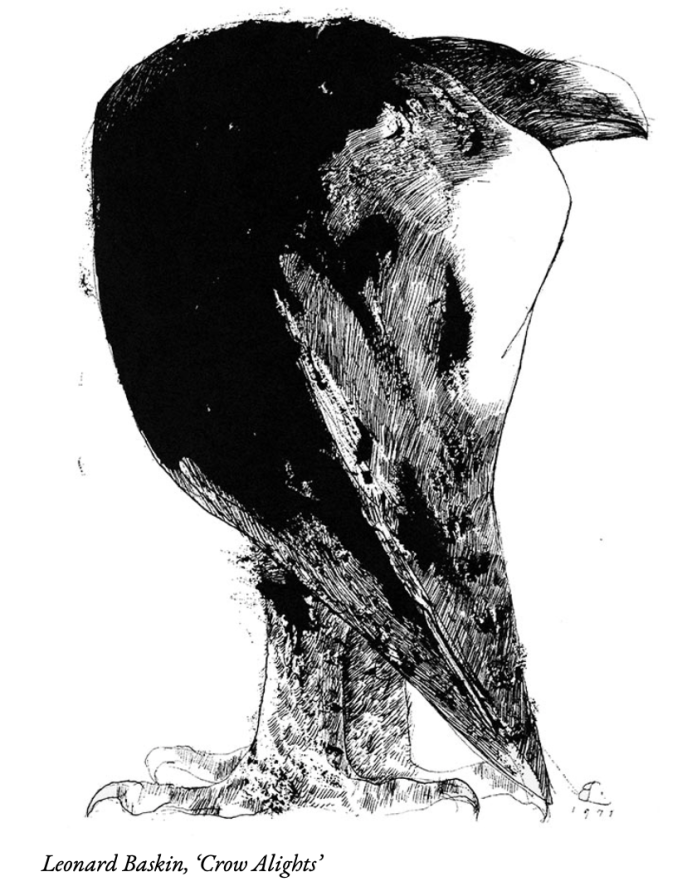

I keep pausing the video as it transitions. ‘Fuck it I love you’ twinned with ‘The greatest’. When The National sing ‘It’s a terrible love and I’m walking with spiders’, what exactly is the ‘quiet company’ of the ‘it’? It could just as well be spiders. Maybe it’s the web itself, the web between the human and the more than human, the gossamer moment where metaphoric articulation becomes more than feeling and gleams material. ‘It’s a terrible love that I’m walking with spiders’ — what is the grammatical transition done by that ‘that’ and who is to blame. Walking with spiders might just be that love. Transitional, subject/object logic is reversed in this song: ‘Wait til the past?’ is sung, then ‘It takes an ocean not to break’ when surely the ocean itself would break you. Soon the ‘terrible love’ is a substance, something ‘I’m walking in’ — to feel it is an act of immersion. It is to let that wave crest over, the ‘lyric auto-explosion’ (Moten 2017: 3) of the wave that would break you.

In ‘The Greatest’, Cat Power sings of former ambition now cast to nostalgic regret. There is a sense of time slowing to delay, laconic strings, relaxed drums, the balladic sleep of a once-held fault. It is a parade slowing down in the rain. To say ‘Once I wanted to be’ is to hold this question of ‘the greatest’ as a generalised desire itself. The hunger we lose in time, whose primary colours soften. I hold to that precious, cornflower blue of a swan’s foot. ‘Two fists of solid rock / With brains that could explain / Any feeling’. This solid rock that would box you into the future, that would harden the edges of self. A thing is born, as Clarice puts it, ‘hard as as dry stone’. This is the thing born ‘that is’. To exist is to be this hard thing, protein ligament, to kick out in lines; but then in time there is the plasmatic self inside that, like some fatty animal byproduct, sticks to the others it loves, it needs, it leaks. Gelatinous, softly sticky love. The ‘it’ that needs saving. Anthropocene softcore; soapy inside of all geologic agency. Who we are and what we regret. The turning of the outside-in, the inside-out. Kathleen Jamie, in Sightlines, asks: ‘What is it that we’re just not seeing?’ (2012: 37).

A sightline is a hypothetical line, from someone’s eye to what is seen. Is it clear or blurred, bad or good? Anthropos recedes in its very own scene as the ocean continues and we howl in the dark like a lossy-compressed version of species. We are the sirens and wolves. We are at the great concert of the Earth. We have to resist what Bernard Stiegler calls the ‘proletarianization of the senses’ (2017); we have to find longform ballads of what’s happening, pass them down the line, resist the short-circuiting of thought that occurs between screens and machines. We have to send letters back to our consciousness, our elders and children. This is the work of lyric. It could be the work of dance. I think of Zelda Fitzgerald’s protagonist, Alabama, learning to be a ballerina too late in her life: ‘Her body was so full of static from the constant whip of her work that she could get no clear communication with herself. She said to herself that human beings have no right to fail’ (2001: 180). Alabama barely eats; her energy is all the zeal of will. The dance of lyric as reduction, lack, as static and chased success whose collapse lands as Alabama will eventually do on the event of inevitable break. Grapefruit squeezed on the gritty turmeric shot of the future. And a brake, a screech. And yet we write, we cast out limbs and materials, we work towards this loss; we imbibe it.

This is an ugly type of writing in which the outside is always imagined from the inside. Horizons are fictional and buildings are barred. I have no sightlines. I’m fucking cutting the corners of someone else’s desire. All paths are the continuation of a pre-existing line. This is a city from which I send myself postcards wherein I wish I was here. Flying letters. Words stolen from myself. I refuse to recognise that I have not composed them unintentionally

(Bolland 2019: 78).

The videos for Lana’s ‘Fuck it I love you’ and ‘The greatest’ swerve between inside and outside. We find ourselves in rooms we don’t remember entering. Writing the anthropocene has an ugly, masturbatory quality of fucking yourself with the rush of elaborate doom. Okay, so. Constructing fortresses of lines which would make a valiant destination. When I listen to Lana, I’m accessing shortcuts to ‘someone else’s desire’ which is the opening up of presence. ‘This is a city’; ‘I wish I was here’. I have never been to LA. We plagiarise our very own diaries to get back that sense of the once-intentional, the greatest declaration on Earth. That we were here, and we loved. She wrote that lit, forgot. The papers curled up and rolled away in a sultry air that was summer, 2012. The year of failed apocalypse, the year Lana released her debut album, Born to Die. We saw her campaign of fashion smoking through plexiglass bus shelters. Remember all ‘horizons are fictional’: they tell a narrative, they bleed and tilt and set like ice. Towards them we stupidly drift: the lived throb of our softcore skins, our hungers and rhythms.

Drifting in colour like H.D.’s Leda, the rape of the land and the body and bodies engendering bodies. Worlds ending around us. And so I could say, but this is just one song, a phrase, a white woman of fame lamenting her world. But this self-conscious cinematics is a gesture towards the western world itself as this haunted, tragic protagonist: ‘The culture is lit and if this is it, I had a ball / I guess that I’m burned out after all’ (‘The greatest’). So you could say, anthropocene softcore speaks to the lyric I in its state of orphaned exception, which in turn is the loss felt by us all unequally. If we make of Lana a sort of anthropocenic siren, we must recognise the distinctions within our longing. For we all lose worlds differently; harm is striated along lines of class, gender, race, ethnicity, geographical distribution — of course. That wave that closes the video could elsewhere be a tsunami. I like to think its place on the edge is a deliberated hint to what could or is even already happening here or elsewhere. And maybe the colour, the aurora, is this streak of need for an excess beyond static blank, ‘human’ planet, standardised canvas; the need to splash something more of blur and blue. Flood the structure.

When we say something is ‘lit’, we mean it is hot, on fire. We mean it is turned on, ignited, intoxicated, drunk, excellent. Lit is the past simple and past participle of light. Isn’t that line alone just lit? Maybe we are in the twilight of a former Enlightenment, recognising our species hubris as this alien green that tinges every familiar horizon, upsets the normalised green of pastoral. Is it toxicity, the elsewhere within ourselves? It is a radar showing who we are and where we have been. Those material metaphors cook on a smoulder, and this is the softcore coming to knowledge about what is happening.

What does it mean to sing: ‘I’m facing the greatest / The greatest loss of them all’. To sing this on the brink of a hyperreal sunset, to chase a solar excess among loss. This loss could be a love but it is more like a culture; it is more like a voice and the condition from which to speak or sing it. The loss of lyric, its possibilities of address, and the loss or deferral or ruination of place itself. Maybe this is Lana’s lyric maturity, a generational acceptance that ‘young and beautiful’ is no longer the apex state of what we should strive for. Absence tenders complexity. Is this, as Roy Scranton puts it, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene? This question of mutability, the green-winged eye that sees a darkening world, a lack of birds along the bay, an edge. In the video for ‘The greatest’, Lana’s jacket reads LOCALS ONLY on the back. I google the phrase and find a hipster restaurant in Toronto with the slogan, LET’s PRETEND THIS NEVER HAPPENED. There’s a kind of parochial nihilism that glisters like the light on the sea, but the sea can never be local only. There’s a boat in the video whose name is WIPEOUT. It’s all happening; the signals are obvious. How we are practicing the absent-presence of the name’s erasure. My tongue gets twisted when I say anthropos; I want to say mess, I fall into ‘guest’ and ‘gesture’. With its glaring cinematics, LA offers the hospitality of light. But it is an exclusionary light. For now, only some of us get lit, get to the mic.

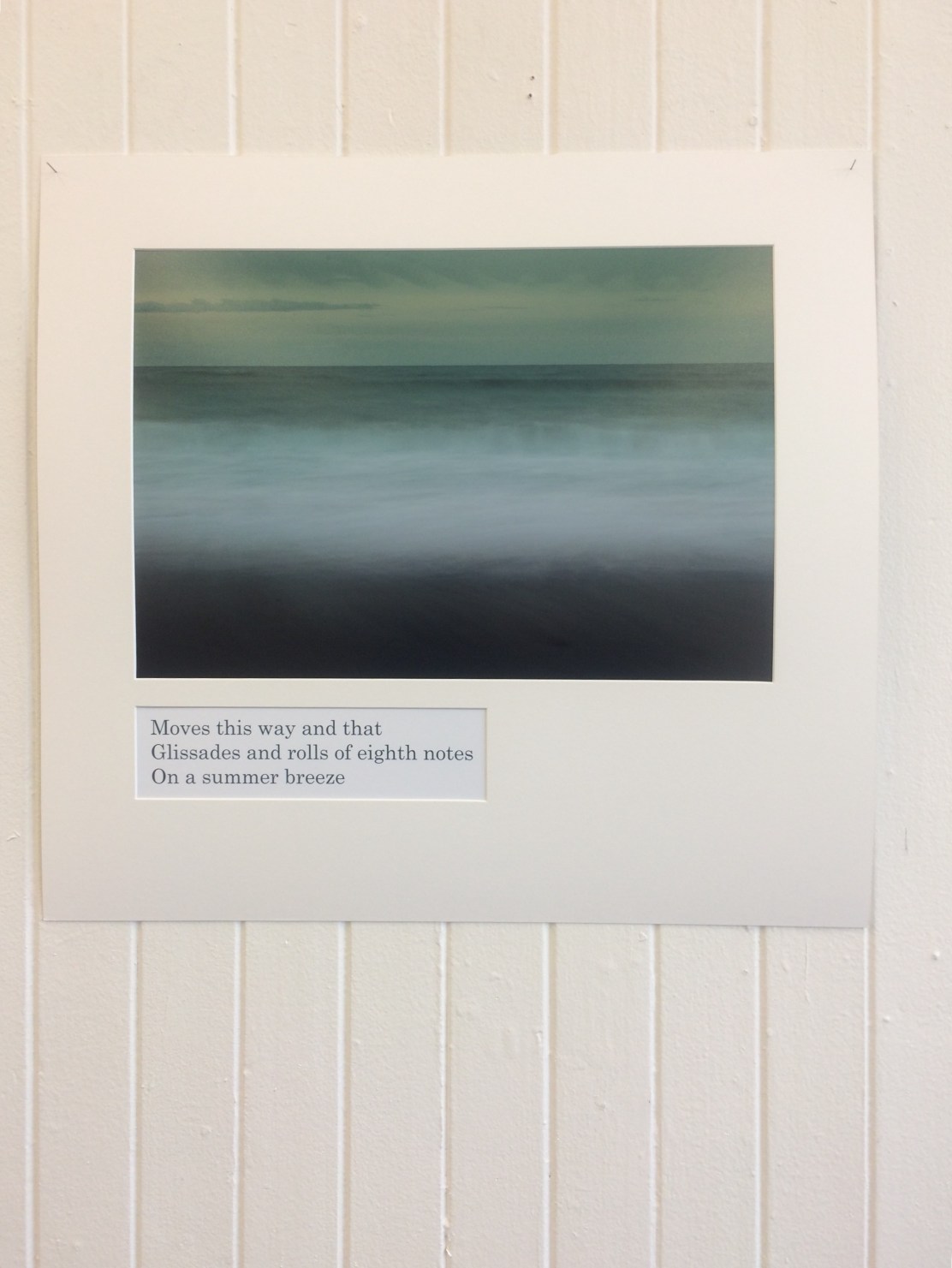

![]()

![]()

Lana sings from within the metallic architectures of LA’s coastal infrastructure, the port. In the bar, she throws a dart and misses her target by a nonchalant smidge, knocks the 8-ball towards its pocket. I keep thinking about exports and imports, what we put out, take in and trade. Economies of luck and depth and surface. Maybe Lana is a hydrofeminist, her soaring lyric gesture recalling a hauntology of America as that dreamscape of what lies beyond or in the deep. And now we know it is further extinction, precarity, hardened borders. What do we do with that looming closure? Lana has shrugged off her jacket now, she’s smoking in the kitchen where the lid slides off the pan to let the steam out. I’m not saying we’re sitting on a pressure cooker here. There’s simply work to do, mouths to feed, ears to fill. This is a ballad, a paean to the transient, fragile beauty of everything. The songs shown again on the jukebox are songs of a type of blues specific to oceanic or cosmic consciousness, to hunger, the time of lost summer or that of a broken love:

Janis Joplin — ‘Kozmic Blues’

Dennis Wilson — ‘Pacific Ocean Blue’

Sublime — ‘Doin’ Time’

David Bowie — ‘Ashes to Ashes’

Jeff Buckley — ‘Last Goodbye’

Leonard Cohen — ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’

I’ve spoken before of what ‘anthropocene sadcore’ might look like in poetry. I’m still working through that. It comes from the common phrase used to describe Lana’s music, ‘Hollywood sadcore’. I’m interested in how that emphasis on mediation, transmission and cinema plays out in our understanding of ecological emergency, but more generally the existential condition of the anthropocene, which places us as geologic agents under the generalised, gendered rubric of Man. Maybe Anna Tsing’s feminist work on the ‘patchy Anthropocene’ could be applied to the cut scenes of a glossy Los Angeles caught on video. A patch is also a software update, where comprised code is ‘patched’ into the code of an executable program. Maybe the patchy anthropocene involves this kind of cultural patchwork: the lament to a love or a culture is patched to include this bug of ecological consciousness — the patch is a kind of coded pharmakon, poison and cure for apocalypse blues. But Lana paints in shades of yellow too. Blue and yellow making aurora borealis green. A cosmic gesture to what lies beyond thought. And what of those oil rigs in the distance, glistening. They form an audience to the siren’s lament; they are part of this story, and we are mutually complicit. Where the magnetism of the male gaze is often part of Lana’s canon, here it is mostly replaced by oil rigs — supplementary Man as the infrastructure of anthropos, looking back at its melancholic, warning siren. Softcore is less affective than sadcore; it is the ambient hum of climax coming. Its cousin is the slowcore, luminous melancholia of a band like Red House Painters, perhaps: ‘Purple nights and yellow days / Neon signs and silver lakes / LA took a part of me / LA gave this gift to me’.

In Bluets (2009), Maggie Nelson writes of a restaurant she used to work in, where the walls were ‘incredibly orange’. After each shift, collapsing exhausted in her own home, ‘the dining room’ of the restaurant ‘reappeared in my dreams as pale blue’:

For quite some time I thought this was luck, or wish fulfilment— naturally my dreams would convert everything to blue, because of my love for the colour. But now I realise that it was more likely the result of spending ten hours or more staring at saturated orange, blue’s spectral opposite.

(Nelson 2009: 43)

Orange and blue, water and flame. The mind’s alchemical transformations reveal the way colour works chiastically upon us. I think of Freud’s mystic writing pad, the waxen surface of memories allowing for palimpsest versions of stories that trace and erase. ‘This is a simple story’, Nelson writes, ‘but it spooks me, insofar as it reminds me that the eye is simply a recorder, with or without our will. Perhaps the same could be said of the heart’ (2009: 43). ‘Fuck it I love you’, sung to the blue-orange wall until something comes off that surface like a static or fizz. Irn bru, ironed blue. There is quinine in my dreams of hungover labour. Surely there is a violence to this particular love, that is staring, necessary. The love of what must be limitless hurts.

Janis Joplin’s ‘Kozmic Blues’ rises to a swell, a jostling of guitar licks and urgent, assured vocals. A sonic thickening. ‘So mastered by the brute blood of the air’, H.D. writes in ‘Leda and the Swan’. Held in that vascular shudder that acclimatises to a manmade world, what happens next is a loosening, a shimmer, a shrug of the garment. In the poem or song, in the painting or film, in the collapse of that wave into a bluer future. To incur a kind of erosion and yet live on in those terminals. ‘There’s a fire inside of everyone of us’, Joplin sings, and I think not of flames but of cinders. ‘At what temperature do words burst into flame?’, asks Ned Lukacher in the introduction to Derrida’s Cinders (1987), ‘Is language itself what remains of a burning? Is language the effect of an inner vibration, an effect of light and heat upon certain kinds of matter?’ (Lukacher 1987: 3). I know if I did not write I would smoke. These acts of temporality in its material extinguishing. What makes the remembered restaurant blue, not orange, is something of this transmogrified smoulder — an inversion akin to af Klint’s swans, demanding that splash of blue. When I write, am I pursuing the absent space of that skyward blue? ‘Blue is the colour of the planet from the view above’, Lana swoons in a song (‘Beautiful People Beautiful Problems’) from her previous album, Lust for Life (2017). But in Norman Fucking Rockwell, Lana’s California album for 2019, it’s less of this ‘above’ we see. We are held within the infrastructure, cinema, the end of summer. The dreamlike logic of How did she get on that boat? When did she enter that room? Who put that song on the jukebox, baby?

I want to say:

It takes an ocean not to break a planet.

It takes not a planet to break a species.

Lana’s voice grows wispier as she sings of that burnout. There’s this imperative that okay we could enjoy this with American flags, we could pour communal Jack and go down in flames. We could riff the history of our culture in archives of song, gestures and nods of reference. Ladies of the Canyon, Cinnamon Girl, Norman Fucking Rockwell. We could keep laughing or dancing while the world is or was at war. Lana is both behind and at the bar, the sightline of where we go to be ‘served’. Intoxication is the order of the day and we call it ‘fun’ to put the fucking of other people’s desires under erasure, strikeout, as Bolland does.

If this is it, I’m signing off

Miss doing nothing, the most of all

Oh I just missed a fireball

L.A. is in flames, it’s getting hot

Kanye West is blond and gone

“Life on Mars” ain’t just a song

Oh, the lifestream’s almost on

(Lana Del Rey, ‘The greatest’)

‘Miss doing nothing’: post-recessional ennui becomes the paradoxical happiness of living in static, not working as a kind of work that resists the future as set out by capitalist horizons of accumulation. We used to just ‘hang out’ and several other dreams of youthful nostalgia. Kids of today can’t even touch that innocence. We know so much; maybe or probably they know more. We are all variously entranced by the softcore unfold of this happening; we are all variously called upon to be complicit, to recycle, act, resist. To speak or not-speak. To be in one of many different levels of rising heat. The conditional state of being’s value, ‘If this is it’, in the anthropocene raises its pitch to a charge. To sign off is a form of surrender that gives up the name for the blur of species. I think of Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, the planet that would smash us and yet somehow Lana dodges it, that.

The audience in the bar where she sings are mostly men, but their gaze is not sexual, as in much of Lana’s prior visual oeuvre. Rather, their longing gaze, often filtered through further glass, is something like the profound melancholy of a multi-generational sense of this loss. These old men have lost the planet, the one they grew up with, just like Lana’s siren, come from some other time, a life ahead of her steered by the changing climate, the hurt and vengeful seas. The camera holds close ups on their staring faces. The song holds the long durée of a loss that spans generations, damages and is damaged by elders, sparks in the present-tense of cultural tendency. In Lana these men look to a future hurt whose cause was partly theirs, as inheritors of industry: she is both victim and heroine, singing and swinging. The shot opens out to reveal her smiling with younger friends, her own generation. These intimacies are what we have left. The next shot shows some kind of factory or refinery leaking smog into a cloudy, overcast skyline, sulphured yellow. Once again the boat appears with its title, WIPEOUT. Lana is supine on the bow at sunset. She is golden, angelic, silhouette. It’s like she missed the fireball but melted it, cooked it up for tea, apocalypse syrup. Things are going down around us. She hugs her arms, later standing, laughing with a dreamlike intimation of imagined elsewhere, closing her eyes. Be hospitable to yourself and others. The reel of the jukebox keeps ever turning: this is our ever faith in culture. We have to take care of what’s left in whatever space we can make of song, duration.

But the mainstream disciples and idols of Hollywood are failing, Kanye West is ‘gone’. Surely a reference to Elon Musk’s plans to save us by colonising Mars, ‘“Life on Mars” ain’t just a song’ is sung with a melancholy matter-of-factness, a kind of sigh which implies the banality of techno-utopia in a time of extinction. The thrill of such dreams is lost now. We lost our faith in Hollywood, lost our faith in the movies and the scale of those solutions. In a world without books, we’d be ‘bound to that summer’, addicted to one of many narcissistic ‘counterfeit[s]’ to make love to nightly in futile repetition — that would be, as Weyes Blood sings, the ‘Movies’.

What we look back with:

The trauma is not, in the Freudian lexicon, this or that violation from the world (such as war), but the ill and trauma of this originary installation of “the cave”—what could properly be called the cin-anthropocene epoch, particularly given that the era of modern cinema is to be regarded merely as an episode: that of the machinal exteriorization of the cinematic apparatus, given that it coincides with the era of oil (artefacted “light”), given that its arc coincides with that hyperconsumptive acceleration leading to mass extinction events, ecocide, and an emerging politics of (managed) extinction.

(Cohen 2017: 246)

The trauma of greatness as such is this accelerated promise of the dream, the event, capitalist growth, the movie itself — whose imperative is towards scene, closure, episodic narrative in demand of the next. But the drinks in this video are barely drunk; they are more like props. Everyone is aware of their place in the tableau vivant of the anthropocene, even in its softcore, consumerist pop expression: the iconography of oil rigs, downbeat affect and intergenerational longing. Not a violation from the world so much as the stream, and where its accumulative logic would eventually come to crisis, even as corporations beyond our imagining were already plotting that logic of a break within archival excess: the feverish incineration of the present, the smoulder and melt that smogs and spreads and streams.

Fire is there or it is not there. […] But surely there is a word for that moment when a fire log, beneath its bark, has become one immanent ember, winking like a City or a circuit board; for that moment when you know only the desire, no, the need to stir it up. What is on fire, you ask yourself, staring into that waiting. What is that moment. What is that word.

(Lennon 2003: 434)

The nights ‘on fire’ that Lana sings of are those of the Beach Boys, reprieve of the sixties; the bar on Long Beach that served as a ‘last stop’ before the tiny island retreat of Kokomo. Frank O’Hara died on Fire Island. Fire is presence or absence, but there is a moment before it is both. A slippage between the extinct and extinguished. And the world was lit up as before. I wonder if the word Brian Lennon looks for is simply ‘sleep’, the title of his essay which I first read in John D’Agata’s anthology, The Next American Essay — with intimations of that Lana song, ‘The Next Best American Record’. What is with America and the positioning of the next. A constant state of pressurised imminence that streams and streams: ‘We lost track of space / We lost track of time’ (‘The Next Best American Record’). We sleep into death or spirit. My first legal drink was a fireball whisky, in a pub by the sea they built in a church. That moment when you know only the ‘need to stir it up’, fanning the flames. That impulse towards blitz feels extra political in these contexts. We need something of relief that would stream, and in that flow be more than a question. Something of cinders, drifting.

In Lana’s song, I’m interested in this word ‘lifestream’, which seems like a slippage from the more familiar internet-lingo, the ‘livestream’: the coming live that seems provisional to digital retro-future, the promise of satellites beaming the present, simultaneously. Lifestream, instead, is a vascular imaginary of bodies flowing together. ‘LifeStream’ is actually the name of a blood bank serving the Inland Empire and its surrounding areas. Lifestreaming is, Wikipedia tells me, ‘the act of documenting and sharing aspects of one’s daily social experiences online’. It is the flow of the timeline, akin to the wall, the blogroll, the feed. But here, at the end of the song, the promise of information’s overflow is in a liminal state — ‘almost on’. Extinction’s monetised data cast as the simultaneity of thick presence spread by millioning participants. We are here and we said something, our words were atoms, splashes of blue. We stream towards a life, cut ourselves short on the fragments of others’ desires. Mortality’s softcore contingent. The fear of missing out is assuaged by the narcotising work of cinema. And if this is it, Lana has already signed off. It’s something more like her spirit that’s here for us, the stream of an echo, fold of a song that we could replay, continue voicing. Hope lies in the circadian rhythm, the lived time of a pause in the anthropocene’s ceaseless, cinematic duration — that which we see and drown our hearts in. As Jean Rhys’ drunken, depressed protagonist of Good Morning, Midnight (1939 – the year WWII began) muses, ‘Well, sometimes it’s a fine day, isn’t it? Sometimes the skies are blue. Sometimes the air is light, easy to breathe. And there is always tomorrow….’ (Rhys 2000: 121). And what if tomorrow was the greatest loss of them all?

~

All screen grabs taken from here (Director: Rich Lee) and here (Director: Natalie Mering).

~

Works Cited:

Bolland, Emma, 2019. Over, In, and Under (Manchester: Dostoyevsky Wannabe).

Cohen, Tom, 2017. ‘Arche-Cinema and the Politics of Extinction’, boundary 2, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 239-265.

Fitzgerald, Zelda, 2001. Save Me the Waltz (London: Vintage).

Jamie, Kathleen, 2012. Sightlines (London: Sort of Books).

Lennon, Brian, 2003. ‘Sleep’, The Next American Essay, ed. by John D’Agata, (Minneapolis: Gray Wolf Press), pp. 427-234.

Lispector, Clarice, 2014. Agua Viva (London: Penguin).

Lukacher, Ned, 1987. ‘Introduction: Mourning Becomes Telepathy’, Cinders, trans. by Ned Lukacher, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), pp. 1-18.

Moten, Fred, 2017. Black and Blur (consent not to be a single being) (Durham: Duke University Press).

Nelson, Maggie, 2009. Bluets (Seattle: Wave Books).

Rhys, Jean, 2000. Good Morning, Midnight (London: Penguin).

Riley, Denise, 2000. The Words of Selves: Identification: Solidarity, Irony (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

Scranton, Roy, 2015. Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilisation (San Francisco: City Lights Books).

Stiegler, Bernard, 2017. ‘The Proletarianization of Sensibility’, boundary 2, Vol. 44, No,. 1, pp. 5-18.