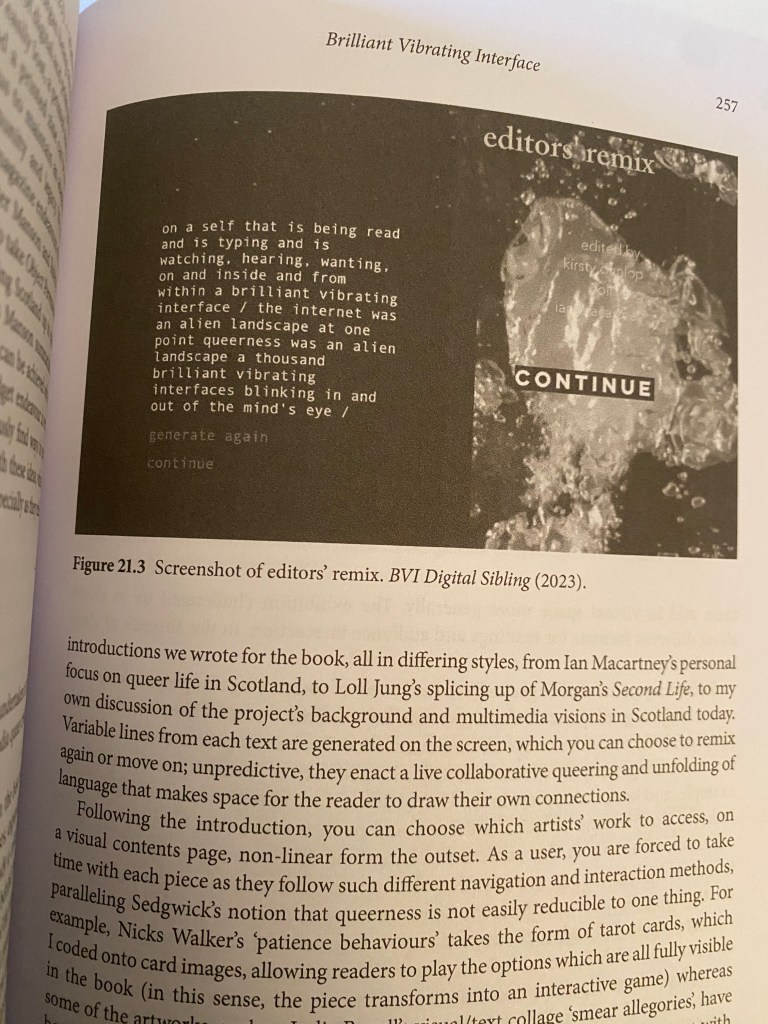

In 2022, SPAM Press obtained some funding from the Edwin Morgan Trust’s Second Life Award to run a year-long project titled Brilliant Vibrating Interface: Queering the Post-internet through Poetry and Practice. My co-investigators on the project were Kirsty Dunlop (SPAM’s current editor-in-chief), Alice Hill-Woods and Loll Jung, with Ian Macartney later joining to co-edit our print publication. We squeezed a lot of activity out of that money: community workshops online and in Glasgow, a few reading events, print publication, ‘digital sibling’ and physical installation, podcasts and an online magazine interview with contemporary sonneteers.

Recently, Kirsty and I wrote an epistolary chapter reflecting on the project and its significance in terms of identity, inequality, belonging, poetry scenes, queerness, Glasgow and the labour of love that is small press publishing. In our chapter we talk about the format of the project, Scottish literary scenes from the nineties to present day and the challenges and rewards of moving between print and digital (what we call SPAM’s ‘resolutely hybrid project’). We explore in more depth the poetry and visual art which found a home in our project and proffer up some poetics for how to think about queerness in the context of ‘small nations’ such as Scotland. This takes us everywhere from CAConrad’s bubbles to Legacy Russell’s glitch feminism to Edwin Morgan’s sumptuous strawberries.

The chapter is out now as part of an anthology, Queer in a Wee Place: Small Nations, Sexuality & Scotland. To quote from the publisher’s website, the book ‘explores identity, inequality and belonging in animated conversations about how queerness moves through place – and how place, in turn, shapes queer lives’. Queer in a Wee Place contains chapters written by researchers of many disciplines and practices – from sociologists to poets – on subjects ranging from the utopic gaze on queer film to legacy and queer elders, disabled queer student experiences of higher education, Scotland’s menstrual landscape, hate crime and queer provincialisms.

The book is available in paperback form for what is a very reasonable price (for an academic book!) from Bloomsbury. You can ask your library to order it in for you 🙂

You can also read it for free via Bloomsbury’s Open Access service here.

Our archive of materials relating to Brilliant Vibrating Interface, including workshop handouts, podcast episodes, interviews and the online exhibition (what we called a ‘Digital Sibling’) can all be found at http://www.spamzine.co.uk and on the EMT website.

Extracts from the chapter below!