like the lake

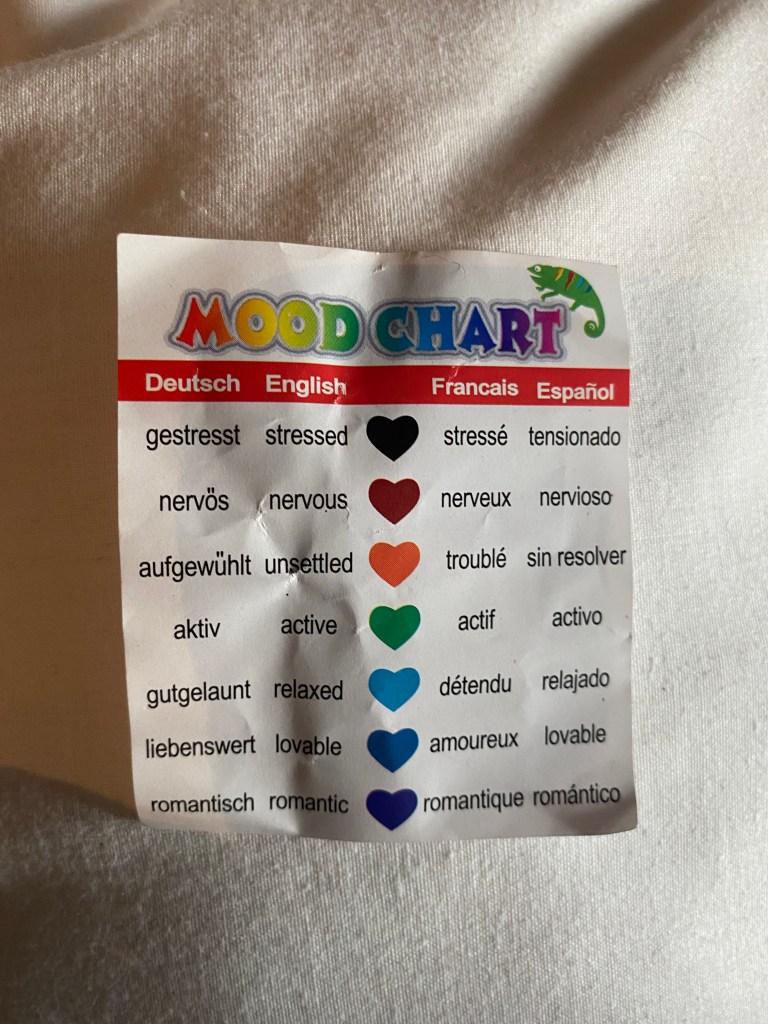

This performance lecture takes flight from the shape of a question: what is the relationship between poetic language, sleep and dream in the anthropocene? Combining poetry, journaling and critical inquiry towards the ecologies of sleep, I will consider how dreams may be the site of impossibility, drift and low-carbon pleasure in a time of ’24/7′ where, in the words of Jonathan Crary, our ability to ‘daydream’ is blocked by a constant barrage of the internet’s attention economy, the demands of late capitalist labour and ongoing crisis. Taking this as a serious political disempowerment, I look to writers whose work alters the ‘operating speed’ of daily life to make room for dreaming otherwise. Exploring the formal interventions of writers within feminist, New York and Language schools, I focus on how these works tend the unruly future garden through daily reclamations of dreamtime. If many of us are at surge capacity, how might poetry attune to various kinds of ‘slow violence’ (Crary) which often go hidden in mainstream narratives of extinction and climate crisis? How might poets borrow from the logic, content and impulse of dream to offer alternative visions of coexistence, commoning, time and compassion for other species?

Recorded at the University of Strathclyde’s Department of Humanities Seminar Series, hosted by Charles Pigott and Hannah Proctor, 4th October 2023.

Those who climb trees with such dexterity as to know how the vertical itself is a kind of knowing. The up-and-down world of clamping fingers and knowing what manner of pressure to apply to manage to hold. I want access to that but I come up against some limit in who I am. A sportsperson would hum in mine ears to try harder. Try to be better is a motto I’ll go with, thanks to a certain poet, but it doesn’t work with sports so much as an ethics for life. Wait. I had this leg on the walls of the world and all it really took was your sweet voice telling me there was a hold. A purple one, a yellow one. Just go for it. A spokesperson would yell in mine ears on behalf of surfaces: it’s going to be alright. I saw videos on the internet of climbers surpassing that moment of freeze to do something amazing like haul their bodies sideways, jump horizontally across the limit, and the thaw on their faces as they landed splat triumphant on the mat. One time another man landed on top of me, I let out a little squeal. It was deliriously exciting. I still have the scar. A rock song. All of the holds became rocks in themselves. You had to find a way to speak to them. If I do this with my fingers, if I really push, if my core could hold out longer for hovering. Suddenly it wasn’t about getting to any top or topping the wall or making that tap of completion. I wanted to find good places to literally hang out, my body a sort of hesitant dying leaf, relishing this thanatos in departing the life-giving branch. My nerve damage screamed in the rigid day. In the cafe with too-hot soup my sap bleeding out meant everything. I have envy for the strength of limbs in those who have earned it, their elastic ecstasies. In my dreams I hung upside down from trees, the frames of swings, the scaffolds of my dilapidated neighbourhood. My hovering grew powerful with longing for motion and soon I would strike a leg up, feel lusty for the whiteout snow beyond summit. Currently, the hardest climb in the world is called ‘Silence’. As I write this, condensation drips from the inside of my window panes, waters the baby aloes, drips like a cat lapping water. I watch a perfect lunar kitten suckle your fingers. The first nourishment. We can’t insulate the thought of my life. I put up my right hand higher than god and clutch.

Bataille wrote ‘affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or a spit’. Losing the self in formlessness is ‘in common with erotic perversion’ and also ‘death’. I’ve always wondered what it felt like to have a galaxy embrace you. All the buried stars popping off underground where your meadow is a whole erogenous zone. Swish the mint wash around my mouth and spit. Blood. Sky stuff.

O how I’d love to swallow wholly and be done with something, star self, in its millions.

Bataille: ‘I propose to admit, as a law, that human beings are only united with each other through rents or wounds; this notion has, in itself, a certain logical force. If elements are put together to form a whole, this can easily happen when each one loses, through a rip in its integrity, a part of its own being, which goes to benefit the communal being’.

Open wide?

Our toothaches in sync and the sky gone down, its scroll won’t work. Clouds clot rain in our gums, I feel sorry for them.

What do I owe you?

Haven’t eaten anything crunchy and good for several weeks, I’ve lost count, there was that pizza at Little Italy that was the last good thing, dripping with goats cheese and artichokes. Formlessness. A gnarly tooth set back in your mouth, meaning something then the lack of it. We drank whisky where the doorman made me empty my huge bag and explain what Marxism was. I let alcohol numb my jaw and stumbled, I was upstairs, sleep weeping in lieu of sleep in a bed, in a travel lodge imagining myself like Sean said to be a larva in a honey colony.

Growing especially acquainted with mush again, less wisdom, I develop fresh desires for attachment. I’m baby for a while, wanting. Scrambled egg, porridge, cherry kefir, refried beans, applesauce, marmalade for no reason, chocolate ice cream, melted cheese, lentil soup, sweet potato, oat milk. Mush has sentience. In your mouth you have its true formlessness and you become one with it. Literally the last few days I’m scrambled, soupy, result of melt. I wanted to be licked thoroughly to nothingness, just this sweetness at the back of your throat.

Jealous of hard edges, hipbones, infrastructure.

Happy Cunny October.

Dentist with claws in my dreams, dentist with dog food in a bowl for me, dentist with a very tall pylon, dentist with a sabre the length of god.

Spider in my shower, spider tattooing itself to my nail, spider has form. Style. Spider in each of my eyes.

Redistribute anything of meat that remains. Bataille wrote of eruptions, necessary expenditures, ‘laceration’. No more content.

You must let the blood clot. No coffee for five days.

Poetics of mush: reduce itself down, a sauce made with the juices released from thought. Tasty essences and tastelessness itself. V Covidian feeling: the only taste is mould, garlic, capers. Salting my kale. You said something.

It hurts to smile!

~

Bataille, Georges, 1985. Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, ed. by Allan Stoekl, trans. by Allan Stoekl, with Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M. Leslie, Jr., (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

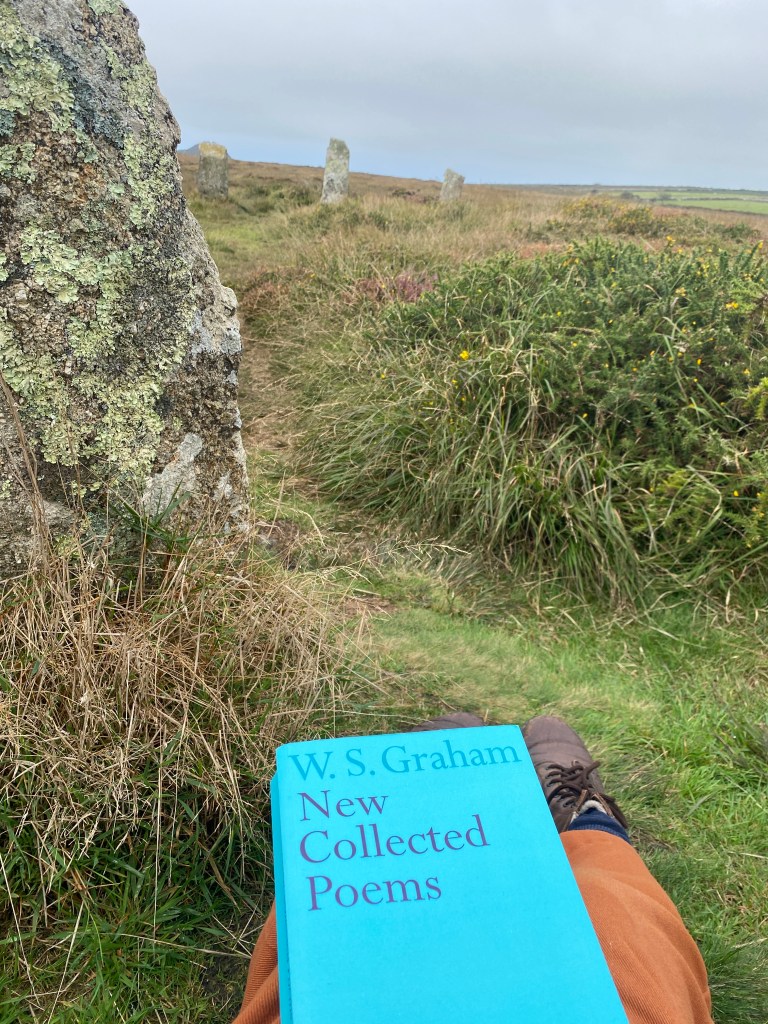

I’m on the twelve-hour CrossCountry from Penzance to Edinburgh. Penzance is the most westerly town in Cornwall and being this close to the edge of something calms me. I always sleep better by the sea. On my way here, on the Great Western Railway, a woman gifted me a glass sculpture with a rainbow inside it, as thanks for helping with her bags at Truro. ‘It’s for stirring your drinks’. For the past week, I’ve been writer in residence at The Grammarsow: a project which brings Scottish poets to Cornwall in the footsteps of WS Graham, who was born in Greenock but spent much of his life down here, making a home of Madron, of Zennor, of the moors. To say this has been a magical week is to say it changed me. I first came across Graham when the poet Dom Hale sent me a voice note of his elegy, ‘Dear Bryan Wynter’, out of the blue; I immediately went out and bought another bright blue, the Faber New Collected Poems. There was something about that foxglove on the wall and the hum of some memory in childhood, watching the bees.

Graham grew up in Greenock, on the Inverclyde estuary. A town where I used to teach writing workshops at the Inverclyde CHCP, taking weekly, then fortnightly trains with our chitty from Glasgow. That time in my life is a blur of shift work, seasonal overhaul, hopeless crushes. I’d get there early to look at the lurid flowers in Morrisons with Kirsty, my co-tutor, or visit the docks alone. Sometimes, I brought my little heartaches to the docks because the air felt smelted, or salt-rinsed, excoriating. The nature of these workshops was that people would share their life stories of such intensity we’d bear them home. I remember one woman writing a story about the moon, ‘we share the same moon’: the one thing connecting her, unconditionally, to her estranged daughter. Many people with stories of recovering from addiction through returning to childhood pursuits: the fishing taught by their fathers, the harbour walks, the musical grammar of language. Graham was trained as an engineer and spent some time on fishing boats, but dedicated most of his life full-time to poetry. The more I learn about this, the more I pine for the shabby romance of that clarity of pursuit. Not as a sacrifice but a great generosity from him, like a penniless rock star.

I’m sure it took a toll on his friends. Graham sent many a letter pleading neighbours and pen pals for the loan of a pound or a pair of boots, once thanking the artist Bryan Wynter for a pair of second-hand trousers. His letters are documents of a life lived in gleaning, bracing the elements, enjoying his wife Nessie’s lentil soup and of course, drinking. On a ‘bleak Spring day’ in 1978, by way of a quiet apology, he pleads with Don Brown, ‘I was flippant in the drink when you came with your news […]. Please let me still be your best friend’. He was often full of fire, a real zeal, taking poetry so seriously but life a strange lark, ‘speak[ing] out of a hole in my leg’. He wrote to his contemporaries — artists such as Ben Nicholson and Peter Lanyon, Edwin Morgan, along with family and friends — with bags of personality, a man self-fashioning in the long blue sea of ‘I miss yous’. As he wrote to Roger Hilton:

We are each, in our own respective ways, blessed or cursed with certain ingredients to help us for good or bad on our ways which we think are our ways. What’s buzzin couzzin? Love thou me? When the idea of the flood had abated a hare pussed in the shaking bell-flowers and prayed to the rainbow through the spider’s web. I have my real fire on. I am on.

The real fire may have been a woodburner, sure, but it’s something lit within him. The letter as a turning on, turning towards: we see this spirit of openness and address in the poems. The real commitment to Lyric. I love the hare that shakes in the flowers with its rainbow religion. I love the flush of arousal from walking uphill at speed. I saw many a spiderweb and two hares chasing each other on dawn of Thursday. On the train home texting many friends as if to have the rush of being held again, ‘Love thou me?’, could I be so vulnerable. A foxglove shook in the wind. The line as a tremble is lesser felt in the steady verse. Clearly, Graham wasn’t afraid of sincerity, though he always took pains to remind his addressees of his roots. ‘No harder man than me will you possibly encounter’, he assures Hilton; elsewhere, after the death of Wynter, he writes to his Canadian friend Robin Skelton of the coming funeral: ‘Give me a hug across the sea. […] I am not really sentimental. I am as hard as Greenock shipbuilding nails’. In a way, the infrastructure of space inflects the language as its face. I’m reminded of a quote by Wendy Mulford which Fred Carter shared at the recent ASLE-uki conference in Newcastle, where she talks about ‘attempting to work at the language-face’. I wear the face of the land, Graham seems to say, and the build of it. At West Penwith, we face the end of the land, literally Land’s End to our west. It is sometimes a silver gelatine, other times a bright blue, a fog grey thicker than thought. A granite-hard land that nonetheless sparkles. I recall a rock on the beaches of Culzean, in South Ayrshire, we’d come across as kids. Mum called it a ‘moonrock’ or a ‘wishrock’. It was a perfectly huge dinosaur egg of white granite. I find this particular rock showing up in my dreams, even now; as if having touched it, I become complicit in a deep time that doesn’t so much store the past as bear its promise. What could hatch from within a rock like that? What could move it, or hold it?

Graham had the idea of poetry’s ‘constructed space’, what I’d call a lyric architecture for reassembling something sensuous in memory or emergence. That this space isn’t just designed (as in my idea of architecture) but constructed points to that emphasis on building. What kinds of muscle, time, effort of spirit and will go into this? The poet Oli Hazzard writes that one of the effects of Graham’s poetry is ‘that I feel like it allows me—or, creates a space in which it becomes possible—to see or to hear myself’. Graham’s poem ‘The Constructed Space’ opens with the line ‘Meanwhile surely there must be something to say’. I always hear it in the lovely vowels of his Inverclyde accent, assuring. Like he’s sitting with you in the poetry bar, two pints between yous, and the poem gives this permission to talk or make space to listen. I think of Denise Riley’s ‘say something back’. My own need always to blurt, interrupt, muse out loud what mince is in my head. It continues:

[…] at least happy

In a sense here between us whoever

We are.

As I write this, light dances on the opposite wall of my tenement flat and it’s prettier than anything given to me by the window. Sometimes my love says I am harsh when they need delicacy, and so I soften the heather of my voice to listen. It’s true that I was happy while reading that poem, a happiness or lightness in the brain as precarious as the light is. Changeable and easily blown further west to let in what fog, or dimness. I don’t mind my brain when I’m in Graham’s poems. By which I mean, it’s no longer a drag to be conscious or sad; things move again, their metaphors in process. There’s a lightness to quietude, its intimate premise, that holds me. Nothing extreme is promised here, ‘whoever / We are’: lyric address sent through ether to find that ‘you’, held in the future’s new ‘us’. It’s better than a page refresh, reading the poem to think something Bergsonian of the self’s duration. I’m more snowball than the first maria who read this. It’s a kind of exhale, in a sense, like Kele Okereke singing ‘So Here We Are’ from an album named suitably Silent Alarm. Imagining my loves at the same time, out in Stirlingshire lying tripping by the loch, their eyes skyward, the high or low. I cherish that wish you were here / so here we are. I can look out from inside the constructed space of the poem. Wheeeeeeeeesht, you. You’ll find constructed spaces everywhere in Cornwall. The lashing blue skyscapes of Peter Lanyon, the abstract panoramas of Ben Nicholson, the ambient plenitude of Aphex Twin (especially ‘Aisatsana’ and most things from Drukqs). I want ambient or abstract art to give me the clouds in my head back to myself, with the light of it. Colours, gestures, fractals, lines.

~

I’ve spent the past week schlepping around the moors and lanes, reading Sydney Graham’s poems and letters, cooking veg on my wee stove and eating simple marmite and butter sandwiches. I have this grandparent on my mum’s side who shared his name, who died of cancer before I was born. Sydney was the name Graham tended to go by, signing letters. It’s not that I’m looking for literary fathers but I stumble into their charismatic arms all the same. Is it guidance I look for, or perspective? I love the rolling enthusiasm, pedantry and chiding of his letters, as well as their cheekiness and charm. His dedication to writing and reading, his swaggering or boastful tendencies after an especially successful performance (coupled with an irresistible gentleness and warmth). His big sweet expressions ‘THE MILK OF HUMAN KINDNESS IS CONDENSED – TTBB)’, ‘IMPOSSIBLE TALK’. TTBB is the slogan of Grammarsow and a familiar exhortation in Grahamworld, meaning Try To Be Better (the title of an excellent anthology of Graham-inspired poems, edited by Sam Buchan-Watts and Lavinia Singer). I summon my voices, I try to be; used to be; want us to be.

There’s a quietude I love about the work, which suits the land and mind. After a summer of working three paid jobs, and two voluntary, I was ready for a gearshift into something relaxed and focused. I’d had enough of my own ‘impossible talk’. Being here was like being given permission to play and explore. Quickly I realised my time didn’t need to be ‘dedicated’. I lived by the cruising whim of the big sky, its scrolling clouds and moodswings. Saw the moon at two o’clock in the afternoon. I watched dragonflies dart between the lanes, listened to my neighbourly ravens at night. Watched big jenny long-legs make flickery silhouettes on the walls. Slept peacefully with spiders above me and the ravens being craven. I wanted all these things in my poemspace, and the poems themselves were initially scarce, then they began a familiar elongation that was comforting, with the swerves of a bus but also the tread of a walk. Some poems wanting to hide themselves between logs where I might later try and find them.

~

A grammarsow is the Cornish name for a woodlouse, or what we’d call in Scots a slater. I remember growing up and having this internal argument about language: was I to go with what my English mum said, or everyone at school? Aye or nay, yes or no. At some point I realised it wasn’t a question of scarcity and elimination, but abundance. The words became barnacle-stuck from all over the sloshes of life, swears and all, and I cherished their stubbornness. Even those gnarly, uncommon words and spicy portmanteau like ‘haneck’, ‘gadsafuck’, ‘blootered’ and ‘glaikit’. And yous: the juicy, plural form of you. Addressing the crowd, the swarm or many. A woodlouse is a terrestrial crustacean drawn to damp environments. I grew up with woodlice crawling out from under cracked kitchen tiles, unearthing raves of them hidden under rotten logs, finding them in tins of old paintbrushes or sometimes a bag of flour or sugar. I always liked the way their little legs seemed translucent, a little alien, and was especially seduced by their darling tendency to curl up into a ball, for protection, like Derrida’s idea of the poem as hedgehog.

Across the English language, there are many amazing names for the humble woodlouse, not limited to:

What is this penchant for lists I share with Graham? I want abundance from something other than products. I’m dumbly monolingual and lists are one of the few ways I can accumulate nuances of meaning. My attention-disordered brain collects lists as procrastination for the Thing itself, what is it I should be doing, always on the tip of some other event horizon bleeding through the last and first, so nothing is really finished. I like that in West Penwith, to look at the Atlantic you don’t see any islands, so there doesn’t have to be an end. You have the illusion that there can always be more time. The sea as this list of limitless light, colour shift, unbearable senses of depth. You are here.

~

The grammarsow crops up in Graham’s letters. In a missive to Robin Skelton, he muses:

And what are we now? Maybe better to have been an engine-driver in the steam-age. A sportsman a shaman a drummer a dancer rainmaker farmer smith dyer cooper charcoal-burner politician dog bunsen-burner minister assassin thug bird-watcher poet’s-wife queer painter alcoholic ologist solger sailer candlestick-maker composer madrigalist explorer invalid cowboy kittiwake graamersow slater flea sea-star angel dope dunce dunnick dotteral dafty prophesor genius monster slob starter sea-king prince earl the end.

Again the ‘steam-age’ of other infrastructures interfacing language. Better to have been a wave engineer in the renewable(s) era. I find myself somewhere between the ‘ologist’ and the ‘angel dope’, strung out on critique, measure and the promise of sensuous oblivion. Not sure if the dope is connected to the dunce or angel, but I’ll claim it spiritually as something good: an enhanced performance. As in, those are dope lines I’m reading. Do you want some? ‘And what are we now?’ not who, but what. A question I want always to ask — it’s almost Deleuzian — with someone in my arms or the sea swishing up to waist height, a sea-star clung to the hollows behind my knees. What’s possible when shame is gone. I love tenderly Graham’s list of possible existences and wonder how many I might retrain as (O genius monster), keeping in mind Bernadette Mayer’s old quip that all poets should really be carpenters. I love the raggedness of letters, which is why I love blogs (letters to the idea of being read). Who are they for? We’re so lucky to have these old ones, bound for us, evidence to the material conditions for our wild imaginaries.

~

In Cornwall, I love falling asleep. I love falling for new poems, stumbling a little on the rugged paths, falling for the air and water, for a little more mermaid’s ale or Bell’s, a blackcurrant kombucha or 100g of coconut mushrooms. In his essay for Poetry Foundation, ‘This Horizontal Position’, Oli Hazzard writes about a time Graham ‘went for a walk on Zennor Hill in Cornwall and fell into a bramble bush’. This falling was a repeat pattern: in 1950 he drunkenly fell off a roof and complained of his three-month hospital stay, ‘I hate this horizontal position’. In my DFA thesis I wrote extensively about lying down as a beginning for writing, the horizontal as a form of refusal when it comes to the upright requirements of an assertive ‘I’. It’s no secret that I prefer poetry in the mode of dreamtime, but that’s not to say I’m also a rambler. It’s a poetry of breath and of steps (of vigour!) I enjoy in Graham. Zigzagging and winding down well-trodden moor paths, stumbling upon bridleways that lead around the hills from holy shrines.

I was the lucky poet to first bless a new writer’s cabin that my host, Rebecca, built on some land near the Ding Dong Mine. From the garden, you can see right out over Mount Bay. The skies are huge here. I’ll say that a lot. I saw a seal down by one of the zawns on the north coast, felt the fear of losing the moon in you, let my lips chap on the telepathy of remote secrets. I try to be better, regardless. My poems become languorous obscurities. All of the land has hidden depths.

~

There was a summer before secondary school when we were gifted an unlimited pass to Historic Scotland, meaning our holidays involved camping across Dumfries and Galloway, the Trossachs, the Highlands, in search of abbeys, monasteries, castles and holy sites in various states of decay. I was turned off by leaflets documenting the actual details of history, emerging sleepy-eyed from the car where I’d been navigating the turgid sentences of fantasy novels or playing platform games like Super Mario. There’s a particular form of carsickness that produces electrolytic effects conducive to imaginative ventures. What I mean to say is, instead of vomiting I overlaid the real world with the promise of portals to elsewhere. In Penwith, I walk off my city sickness and sit by the standing stones, quoits and old ruins of industry. What do I imagine but a ‘news of no time’, still to come? Zennor Hill is both poem and place. The more I’m here, the more a sort of aura thickens.

On my last morning, I wake to sunrise over the sea. Dew shimmers the rosehips. The air is earthsweet as ever and I don’t know how I’ll go home. Travelling is an experience of dislocation: here, I find home again in language, its caught habits, Graham’s words sluicing Clydewards. There’s a poise to his poetry, steadfastly composed as ‘verse’ and often by iambic measure. Making perfect prosody with the chug of the train. I was pleased to roll into Glasgow having bumped into my friend Kenny, the whisky god of the Hebrides, attuned to the flight-pulse of conversing again. Hungry, ‘putting this statement into this empty soup tin’ to say cheerio as Sydney would, lighting up poetry to finish it, the best thing of all, a warm scaffold to hold up how we missed each other. A quiet disintegration of cloud. What are we now?

With thanks to Andrew Fentham, David Devanny and Rebecca Althaus for kindness and hospitality. Long live The Grammarsow!

A few weekends ago marked a whole year since my exhibition with Jack O’Flynn, The Palace of Humming Trees, curated by Katie O’Grady. It was the height of summer, electrified by lightning storms and rain showers which sent the city streets flooding my ankle boots. I sat in the exhibition watching the auras of animals, drifting in and out of presence, doodling, planning short fiction I’d never write. The rain came down through the ceiling, just a little, and caught in a bucket. I texted in streams.

Something of the exhibition magicked itself into existence. We were all ’93 babies. Making things happen felt so easy. There were synchronicities and invincibilities. When Katie and I hung out at Phillies, we won the quiz. Jack and I wove this hyperplane of fantasy from the gestures of clay and line, whittling and glitter cast wide across floorboard and spiderweb. It was a strange time, the summer of 2021. I was also partially in the numb haze of grief. There was a delta wave but not like the deep sleep of the sea. People brought champagne and flowers to the opening. I wore a long white dress and wished the days were as long as they used to be. The Earth spins too fast.

Partly I wanted to write in the choral voice of many creatures speaking to one another. The process felt like a lyric surrender to this collective, their hyperintelligence of humming and stammer that spoke through pores, chitin, liquid. I don’t know where they learned all this. There was a sun virus in the emails we sent the summer before it. Time freckled on my arms. I could draw out the muscle ache from cycling more. It was possible then.

Anyway, about this experience of writing. A porous voice. Here’s an artist’s talk from a recent conference.

First delivered at Hear them speak: Voice in literature, culture, and the arts

10th June 2022

Who might be the ‘they’ in K Allado-McDowell’s statement? Taken from Pharmako-AI, published in 2021 and the first book to be co-authored with the neural network GPT-3, a system trained on extensive web data (from Google Books to Wikipedia), the quote suggests voice, presence and identity are questions of patterning, replication, weaving, plurality. Recurrent in Allado-McDowell’s book is the figure of the spider and its web, in a kind of constant movement like thought itself.

I was travelling north on a train when I began writing The Palace of Humming Trees, a book-length exhibition poem which forges energy fields of dreamy relation between many species of animal, mineral and element. Late spring and the fields I could forget about, texting myself more poem. The motion of the train according inverse to the downward scroll of the document. All the while seeing spiders in the corner of my vision, emitting great clots of silk. Commissioned by curator Katie O’Grady and made in collaboration with the artist Jack O’Flynn (both from Cork, Ireland), the exhibition was to offer something of a ‘hyperspace’ to its viewers: somewhere in which voices coalesced, formed new modalities of being and relation, new webs. In a Tank Magazine interview with K Allado-McDowell, Nora N. Khan notes that hyperspace ‘is an abstract space in which we perceive patterns of information and then shape them in language in order to communicate’. Having a big, serial and open field poem adjacent to visual work premised on bold, ecstatic colour and texture was to perform multiplicities of voice within an otherwise abstracted work. Inspired by Timothy Morton’s ideas of ‘dark ecology’, adrienne maree brown’s ‘pleasure activism’ and Ursula Le Guin’s ‘carrier bag theory of fiction’, I wanted to think about that communication as a form of attunement through which we gather, desire and coexist as ecological beings.

In The Palace of Humming Trees, the lyric voice is taken as that trembling spider silk assembling worlds. Spider silk is a protein fibre which embodies the inside of the spider woven on the outside for shelter, cocoon, courtship or the trapping of prey. It’s five times stronger than steel and is now being synthesised to make everything from body armour to surgical thread and parachutes. I began imagining the twangling of droplets on silk strands as the visualisation of a deep vibration, perhaps the wood wide web – something humming in and between trees. The world of the exhibition was inspired by the Irish folktale, The Hostel of the Rowan Trees, also known as Fairy Palace of the Quicken Trees. In the story, trees of scarlet fruit provide refuge, but the fruit itself (the quicken berries) are highly desirable to the point of despair. The rowan was brought from the land of promise, and its berries offer rejuvenation. With these symbolic undertones of danger and desire in mind, we wanted to explore a mythic ‘palace’ which merged the digitality of hyperspace with the organic textures of woodland and the chromatic intensity of dream, fantasy and ethical relation.

At the heart of our project was a notion of infinity. Hyperspace suggests that our ecological sense of world, surrounds, habitat, umwelt is always being reassembled. I wondered if infinity could somehow be voiced in a way that wasn’t just postmodern recursion or echo. What does it mean to be open to a state of infinity? To let many worlds pass through you all at once, making diamond-like instants and gossamer patterns of prosody?

Infinity became our figure for ambience. As spider silk is densely structured, and the neural net densely layered, so the notion of ambience captures, in Brian Eno’s words ‘many levels of listening attention’. To walk through the door of The Palace of Humming Trees was to enter a portal of multiplicity. You could take any route you liked around the room, moving between sculptures of hyperfoxes and sparklehorses, lichenous forms, ceramic butterflies of psychedelic hue and illustrated groves where trees shimmered green, orange, purple and blue. You could also scan a QR code and choose to listen to a recording of the poem, voiced by Jack, Katie and I and accompanied by Dalian Rynne’s sonic dreamscapes. To hear something ‘humming’ is to sense its presence, even if you can’t wholly understand it; humming implies electromagnetic vibration, birds and bees, a weather event or tectonic movement. We weren’t interested in translating the more-than-human voice so much as bringing it into the forcefield of lyric poetry, and through that expansive patterning achieve ‘infinity states’ of reassembled meaning, of felt experience that could not be crystallised into singularities of being. Visitors took pictures, sketched Jack’s sculptures, ran their fingers through the luminous plaster dust, placed to highlight the debris or excess of our clay animals. Something always in the process of creation or decay, incomplete. Corporeal, yet infinite.

One of the many voicings of this project was Letters from a Sun Virus, a correspondence between Jack and I that occurred over the first Covid lockdown, documented at the back of the exhibition book. While the email exchange had distinct senders and receivers, the you and I, over time in collaborating and sharing work between the visual and textual, our voices were beginning to mingle. Sometimes this co-voicing was painterly; other times musical, inflected with the characteristic intonation and energy of our respective speech patterns, moods, expressions. An entry from April 2020 reads: ‘…the wateriness of the poem. I had completely forgotten about all that blur. It’s like all the brush of the ocean and one which seems the idea to spill that way. Almost like a pressure, lines that go on and hair turning into the sea, each one of kinetic energy then finds all these points’. To assemble the correspondence for publication, I plugged it through text remixers, copying, pasting and rearranging phrases to enhance that sense of two voices repatterning one another. A ceaseless quest for points; for elements acting upon objects, emotions. Denise Riley has written of ‘inner speech’ as a strange oxymoron, where one hears voice at the moment of issuing voice inside us – a kind of running commentary that hums without actually humming. The letters suggest a kind of inner voice infected by the anticipated response of the other, rendering intimacies of collaboration which form a sticky substance, sentences and mobius formations holding time’s play and repeat – ‘Unending loop of my dream resins / not to complete the palace infinity of these trees’. Imagining the many of them speaking.

In Texts for Nothing, Samuel Beckett writes:

Whose voice, no one’s, there is no one, there’s a voice without a mouth, and somewhere a kind of hearing, something compelled to hear, and somewhere a hand, it calls that a hand, it wants to make a hand, or if not a hand something somewhere that can leave a trace, of what is made, of what is said, you can’t do with less, no, that’s romancing, more romancing, there is nothing but a voice murmuring a trace.

To ask whose voice in The Palace of Humming Trees is to hear sound bouncing as light, romancing, refracting in what Katie, the curator, calls a many-panelled ‘vivarium of humming thought’. To say ‘there is no one’ is to declare at once absence and the impossibility of presence as a singularity, there is no ONE. What if voice was infectious, modular, sporous, erotically charged, in common? Early in the project, I had this conversation with Jack where he told me that sometimes in the process of sculpture, he’ll try turning something upside down, or inside out, to revitalise the work. Make it strange or more-than. To sculpt by hand is to ‘leave a trace, of what is made’, and to write is to leave a trace ‘of what is said’. I wondered if the inner speech of the lyric ‘I’ could be turned inside out, to be exposed to the grain, the noise, the weather. A voice that touches is and is being touched, traced, smudged. I imagine this book as a glasshouse, somewhere between inside and outside, shelter and exposure; a chamber music of alchemical voicings, always repatterning, transforming each other. Sound and light. A place of invitation, ritual attention, metamorphosis. Many selves stuck to the web of a visual, expansive language.

cn: mention of bulimia; spoilers

It’s been a fair while since I posted. Struggling through Covid, another supercold (emerald phlegm forever), more transitions, finishing my thesis, April snow, more streaming of the body and ache, but here we are. It’s good to get words down. I can’t smell or taste anything at all right now (coffee is just…neutral earthiness, sweet potatoes are…mush of the orange variety, bread is…send help) — so the vicarious pleasure of language is all the more heightened. Sometimes it’s a barrier: why read about anything when your senses don’t respond? I’m drawn to the elliptical which doesn’t hold me for too long. I want to be let go or dissolve a bit. Like eking my reading through a fine mesh of muslin, a semi-permeable membrane of comprehension. Or pull it over my head, this paragraph, the whole fabric of the thing. I was gonna write about a month’s worth of reading: mostly while walking west to east along the polluted, outer commuter belt of the city; on trains between Glasgow, Inverness, London, Leeds; in frail, unwaking mornings; at the park, in that golden week, sitting in the grass with salad from Juicy and daffodils. Instead I wrote about sleep.

*

Finally I got round to reading Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018), a book I wanted to read especially because a trusted friend described the ending to me as ‘disappointing’. I love to glut myself on disappointment. For some reason the novel produced a similar effect on me as Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005), in that the pleasure was all in the premise. I would love to exist endlessly in the loop that is prolonged sleep or the reconstruction of a highly specific sensory memory. I want these novels to just go on and on like that. Of course, there has to be escalation, as per the rules of plot or ~human nature~. Is it true we can’t circle the mobius loop forever? That after a while the pleasure is desensitised, and we need to dialup on the extremity? McCarthy’s novel sort of preserves that perfect figure of eight in its set-piece ending, and you’re left with the image adrift to loop back on the primal, inciting moment of falling debris and trauma. I found the Moshfegh ending ‘cheap’ in that it seemed to cash in its bulimic character for a kind of tragedy whose fate was to fall. Bulimia, I can say, is generally an experience of permanent insolvency in the body, resulting in a loop time of binge and purge. You pay the debts of fasting by devouring; you pay the debts of eating by purging and fasting. Rinse, brush teeth, ouch, repeat. The sociologist Jock Young talks of ‘bulimic society’ as one where the poorest and most marginalised are often the most culturally enmeshed in the desperate iconography and desire economy of consumerism. The most excluded populations, according to this view, absorb images of what is apparently available under the veil of late-capitalism; but simultaneously they are rejected from accessing this culture themselves due to material inequality and class difference. As Young puts it: ‘a bulimic society where massive cultural inclusion is accompanied by systematic structural exclusion. It is a society that has both strong centrifugal and centripetal currents: it absorbs and it rejects’. But does capitalism spit us out or do we boak back? This is why I am scared to go on TikTok, like fear of lifestyle saturation to the point of nauseating breakdown.

Often powerpoint slides defining bulimia for this sociological context mention an ‘abnormally voracious appetite or unnaturally constant hunger’. In Moshfegh’s novel, the character Reva (an insurance broker) is constantly eating or constantly fasting; something our protagonist describes with pity or nonchalance. Reva is tragic because she wants too much what the protagonist effortlessly has by birth: beauty, thinness, style, money. Thinness is kind of the ur-sign for WASP privilege in the aftermath of the heroin chic fin de siècle. Reva is jealous of the protagonist’s weight loss, steals her pills. Both women are after control (or its relinquishing) in a world in freefall.

This is a period novel: set in the early 2000s, New York in the lead up to 9/11. It’s full of that inertia following the boom of the 1990s. The desire to just sleep in the unit of a single year is like a microcosm for not just an end of history, as per Fukuyama, but a refusal of history altogether as this thing that keeps growling, accumulating, disrupting sleep. I kind of buy into Reva’s bulimia as something about the consequence of being voraciously invested in a world that wants to expel you, sure. The sky’s big whitey’s the limit around Manhattan. Chewing on this feels productive. The violence of the novel is primarily in the gallery where the narrator starts out working. The gallery’s prized artist, a young man called Ping Xi, has these ‘dog pieces’: a ‘taxidermied […] variety of pure breeds’, which are rumoured to make their way into the artist’s exhibition via premature slaughter and industrial freezing. The work apparently ‘marked the end of the sacred in art’. The narrator is kind of offhand disgusted but eventually comes to identify with the young animals in the freezer, waiting to be thawed into art. Writing can be a bit like self-cannibalism; the denial of which leaves you stoked for a snack.

There are several kinds of hunger in the novel: primarily for sleep and food, but also for meaning, intimacy, loyalty. Love is a strange relation that moves uneasily between two girlfriends whose friendship is based on a premise of inequality and co-dependency. The hungers are sated by devouring emptiness. Sleep, junk food, fleeting talks. That bit in Melancholia where Justine screws her face up deliciously and says the meatloaf tastes like ashes. When I realised the same of my dinner, I didn’t even react.

We look more peaceful when sleeping. It’s worth lauding, like Lana singing Pretty when I cryyyyyyyyyy………….

O, and the concept of the sad nap:

There was no work to do, nothing I had to counteract or compensate for because there was nothing at all, period. And yet I was aware of the nothingness. I was awake in the sleep somehow. I felt good. Almost happy.

But coming out of that sleep was excruciating. My entire life flashed before my eyes in the worst way possible, my mind refilling itself with all my lame memories, every little thing that had brought me to where I was.

(Moshfegh, My Year of Rest and Relaxation)

The brutal awakening cashes in on the extra expenditure of napping. I’ve written in a poem somewhere, ‘I wish I could sleep forever’. It’s different from wanting to die. It’s more like, wanting to feel aware of the nothingness and calm in its premise. Nobody needs anything from you and you can’t give anything back. It’s restful or at least prolongs the promise of rest. Stay awake super late to relish the idea that you could go to bed. I don’t remember the last time I woke up feeling energised by sleep. </3 I remember listening to an interview with the editor of Dazed where he talks about sleep being his great reset. I remember thinking wow sick cool. Whatever mental health thing he’s going through, sleep will heal it. Sleep can otherwise be a kind of emulsion of depression. You’re in the weight of it spreading right through you. I carry sleep along even when I don’t ‘have’ it.

I want you mostly in the morning

when my soul is weak from dreaming

(Weyes Blood, ‘Seven Words’)

I used to wake up extra early before school to steal back from sleep. I felt sleep would eat me alive. I used that time to browse the internet, write, read. Eat shitty muesli. Puke.

I’d sleep in class. Teachers would bring it up at parent’s night. I just couldn’t understand why everyone else wasn’t regularly passing out over their schoolbooks.

The perma-arousal of bulimia is a counternarrative to the inorganic sleep cycles pursued by the novel’s main character. I got a similar vibe from watching Cheryl Dunn’s Moments Like This Never Last, a documentary snapshot of the pre- and post-9/11 world of New York’s underground, showcasing Dash Snow’s graffiti and outsider art. Dash is always cheating sleep to go tag, paint, take pictures. There’s a ton of cocaine and consequence. 9/11 had toppled right through all of that leaving a wound. You know by the law of entropy that it can’t be sustained, this life, writing on the walls and all that. Maybe tagging is also about a kind of hunger-purge. Colour’s aerosol vom marking time, presence, ideas. It’s permanent, but then someone can just go clean it up; the ultimate fuck you.

Whose space does this belong to? Remainder is a novel about gentrification, the white guy’s obsessive reorganising of London spaces as precursor for the gentrification of Brixton. A novel of the zombie flaneur, fuelled on flat whites, iPad swipes and vape juice, as Omer Fast’s 2016 movie adaptation brings into focus. Moshfegh’s novel is set around the same time, but her protagonist is decidedly not a flaneur, even if she carries that vibe of the waking dead. She barely leaves her apartment to get coffees from the local bodega, and when she does venture further it has all the amnesiac disaster of a night on the NY tiles with Meg Superstar Princess, furs and all. I find this zombie existence an irresistible metaphor for the numbing effect of late-capitalism: we are overstimulated and aroused to the point of just turning off. It’s banal to say that, sure. What’s great about the Meg Superstar Princess blog girl revival is the way the writing itself is charged with like, full off-kilter zaniness. The opposite of zombie. It’s like barhopping around A Thousand Plateaus — cheap wine in one hand, vintage Android in the other — to the tune of Charli XCX and it’s absolute chaos: ‘spitting e pillz out my mouth, trying to live normal, disco n apz’. You get smashed. You’re alive! I’ll have it in writing because I can’t really have it elsewhere rn, the same way I sleep but I can’t really sleep. Apps (f)or naps?

For all this tangent on (post)pandemic hedonism (let’s say post to mean, posting and not to signal some wholescale shift in era), it’s weird how history just hits you in the face at the end of Moshfegh’s novel. Falling debris, bits of glass. Words:

On September 11, I went out and bought a new TV/VCR at Best Buy so I could record the news coverage of the planes crashing into the Twin Towers. […] I watched the videotape over and over to soothe myself that day. And I continue to watch it, usually on a lonely afternoon, or any other time I doubt that life is worth living, or when I need courage, or when I am bored.

(Moshfegh, My Year of Rest and Relaxation)

Earlier in the novel, she’s frustrated when someone replaces her VCR player with a DVD player, even though she doesn’t have any DVDs. She kind of hates the concept of the DVD. She likes the process of rewind. Video tapes, with their seriality, make you confront duration; whereas DVDs allow easy random access to specific scenes. The over and overness of Moshfegh’s careful, clean, lethargic prose is at once soothing and disturbing. When the pandemic first hit, I couldn’t stream anything because the thought of having all that content at my fingertips seemed appalling. Like accessing a trillion orderly dreams of someone else at the very moment I couldn’t even touch another person. Maybe video tapes would’ve been different. The residue of wave matter at the edge. The analogue sense of fossilised images, decaying in visible time.

In a poem called ‘Along the Strand’, Eileen Myles is like,

The times of the day, the ones

with names, they are the

stripes of sex unlike romance

who dreamlike is a continuous

walker

I love the rhythmanalysis of daily life here. VHS stripes in descending order of luminance: white, yellow, cyan, green, magenta, red, blue and black. How the speaker clings to named moments of the day as like khora: receptacles unseen for adhesive feelings. ‘Vigorous twilight’, ‘noon’ you slip into, ‘Morning’ as ‘something / I could stay with’. The times of day are lovers. If romance is continuous walking, there’s not a lot of romance in My Year of Rest and Relaxation. So after reading the novel I’m sorta stuck on wanting the romance of sleep again. Exhalations as stripes of sex. Like when you have a new partner and after a few weeks of breathless sleeplessness suddenly the first thing you realise is how well you’re sleeping, like being beside them all night just fixed your life. And so to be in love you know noon tastes different, and twilight has a lilac halo. And you’re sharing this shiny sticky static in the air like asterisks, so much more to say.

*

Sleep. After a long walk, I remember circling South Norwood Lake and humming Elliott Smith’s ‘Twilight’, because of the time. You asked me to sing it. I had a low voice, a high voice. I was just waking up; the air was all lavender, leaves in fall.

I don’t want to see the day when it’s dying.

It was supposed to snow in the night and the not snowing was sore as a missed period. I awoke with two crescent-shaped moons in the palm of my hand and thought of a sacrifice unwittingly given in dreamland. Said Jesus. Peridot phlegm and the scratchy sensation, knowing that speech too could be cool, historical, safe. Could not see beyond pellucid rivulets, Omicron my windows, my streaming January. January

streams from every well-known orifice of the world. Its colour is shamelessly stone. I seem to be allergic to inexplicable moments and so keep to the edge of the polyphony of yellow. I am cared for. The Great Barrier Reef dissolves in my dreams the substrate of yellow. It goes far. Pieces of the GBR are washed ashore in Ayr, Singapore, Los Angeles, Greenland. I go to these places by holding a polished boiled candy in my mouth, like the women in Céline and Julie Go Boating. My ankles licked by truest shores / but January didn’t fucking happen.

❤

Put together the orange-purple rose, your possible outcomes are red or gold (if you are lucky). Two reds together, with the golden watering can, could result in the rare blue rose. A novel rose. Black velvet roses grow in the old woman’s garden because she has infinite time to tend them. I’m not saying she’s immortal, like the Turritopsis dohrnii jellyfish; only that she doesn’t exist in our time. It’s rude to assume so. I’m not saying the lines of her face are asemic writing — nobody did that to her, or scarred her. She’s not scared. She just lives and dies all the time. She waters the roses.

Sometimes I imagine her in fisherman’s clothes, in meshy nightclub outfits of neon flavours, in extravagant ballgowns, blue boilersuits. Sometimes I’ve seen her before. The only way I can see her is to climb a few steps on the ladder by the village store, its red paint flaking, and I hang my body upside down the other side, risking exposure. I never eat before doing this. She doesn’t see me; she doesn’t see her roses either, not the blooms. In the village, people walk around with handfuls of rose seeds sometimes strung in little hemp bags. These are the currency of care. I have tended the young with haircuts and watched the flourishing of teenage roses. They say I am an old lady in the garb or garbage of former actresses. I hear them sing to me their stories. “Remember

she shot the guy who brought the astrograss”.

What they don’t remember, whippersnappers, is the incorrigible realism of that turf. Fuck it,

I have done nothing wrong. I perform for them my cowboy gardening. Broadcast the surplus value of our mutual twilight. Halloween roses for everyone. Every night I wake up from someone else’s childbirth and the world is so sore, the wound in the sky the snow wants to fall through. They bandaged it with realism. I need to go far. Do you remember the last time you awoke and felt like a person?

❤

The roses grow up in the gaps of the cattlegrid, knowing they will be trodden on. Again and again. We can’t stop them from doing this and they do it so often we have to account for a portion of Waste. Kissing you is itself a trellis. But we are propped and grown sideways with the vines strung betwixt our ribs. We are babies.

I like the tired way the roses intonate colour. The economics of the roses. Their euphemistic fetish. I tried to avow my commitment to rosehood the day I saw your calves all torn, and saw about women getting their labias reduced, and the red, blood roses sold on the internet, and rest. I lay this on your grave, the world.

My love, as a redness in our rosette

That’s newly worn in June

O my love, like the melt

That’s sweetly played in turbines

So fairway artery thou, my bonnie lasso

Defiled in love as I

Will love thee still, my decade

Tinged as the seas are garlanded dry

Tinged all the seas as thee, my decanter

At the romantic menagerie of sunset

I will luminary still, a debutante

Of the lighthouse sarcophagi

And plough thee well, my only lathe!

And plough thee well, awhile!

And I will come again, my love

Though it were ten thousand millennium.

My love’s rose-coloured highlighter really hurt the extra-textual, and thus booked trains to bed. I had an identity. I knew what you had done to the text. Austerity of the meadow to blame for ongoing culling of kin. You are abandonable as you have always been. Saplings for pronouns.

I feel wild and sad.

I feel pieces together stirring inside the world. Little bits of coral awake in

my throat, the shape of eight billion sun-spike proteins I was dumb

enough to swallow. It is not my fault but in my dreams

I get product emails like, Forget-me-not

a pair of jeans, high-waisted Levi’s

as if to wear at the end of the month

we keep saying sorry for delay, embroidered

our thighs with spiders

excuses to use lighters

without smoking

does it make us vectors

the warning of snow and ice still issued

from inside the snow globe of the rosehip

changes as it withers, glass shards

pissed from acid clouds in all colours:

black, blue, burgundy, cherry brandy, coral

cream, dark pink, green, lavender, light pink,

lilac, orange, peach, purple’s timeless red,

salmon, Hollywood white & yellow, rainbow

chosen for the significant other, a masculine flower

dipped in fortified light, I’m thankful

I look good lying down, the long unconditional stem

aka Lemonade, l-l-l-lemonade, l-l-l-lemonade…….

from Alice Notley, The Descent of Alette (1992)