In 1993, the World Wide Web was released into the public domain. There are many histories of the internet and this one is pretty idiosyncratic. I like asking people when they got their first desktop computer. The internet of 1993 could be navigated through bright blue hyperlinks and you would drift between websites. You would type stuff into AskJeeves and have no idea what to expect. At school we had a ‘passport to the Web’ certificate that could be obtained by completing numerous training activities on a twee little software whose name I forgot. It was something like ‘CyberKids’ though surely that is a New York City raver subculture from a time not yet captured by the sleazification of all things indie 2000s. I imagine it was superior to the present Cyber Security Training on offer, in which actors pretend to discover pen drives in the street, gleefully insert them into work desktops only to find their screen literally blowing up in front of them. Nowadays, cyber security training is less about don’t talk to strangers and more about change your passwords regularly. I have a lot of floaty metaphors for the password changing which seem to all include underwear or car parts. Passwords though are pretty boring, clunky things but they’re also gauzy ephemera. Pieces of secret unlocking. Recently I spent an entire Sunday trying to unlock a 2011 MacBook. The password, when I found it again, accessing the deepest recesses of abstract memory, was unforgivably cherishable. I’ll keep it forever like a pet (I’ve already forgotten it).

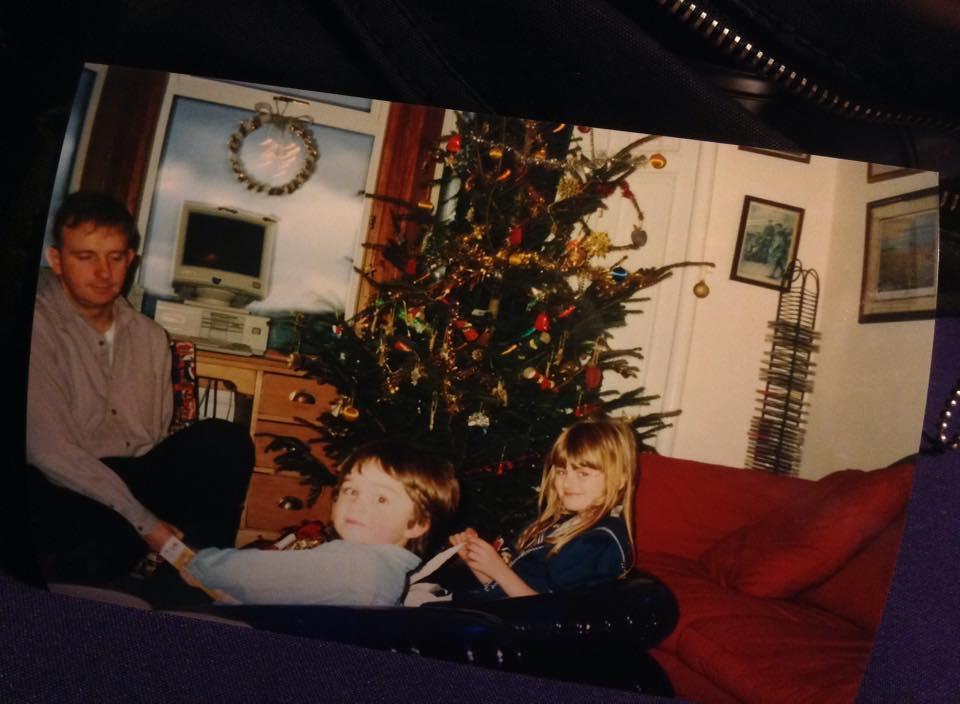

I keep thinking about ressentiment as a sensation produced by the internet. I mean the internet’s failure. When I was a child, I adored the internet. Once we’d upgraded from dial-up, I would spend upwards of 12-14 hours almost nonstop on forums, games, LiveJournal, websites. I gravitated naturally from the virtual worlds of the Game Boy to the bigger screen of the laptop. Before I was even allowed internet access, I would simulate them by making endlessly complicated Powerpoints and Microsoft Publisher pages which connected to one another like a crude open world. I was beset by RAM crashes and Wi-Fi outages. We didn’t have broadband for a very very long time. My dad was one of the first in the village to have it. I would write letters to the broadband guy pretending to be my dad complaining about the speed of the internet. When I go back to the Shire now, I say things like ‘the internet here is ass’. I can’t get 4G at the semi-demolished and barely functioning station. We can’t find out if our train will come or not. We communicate as a brooding micro crowd, frowning and looking anxiously towards digitised screens whose flicker says only ‘delay’. There are no staff. The staff hide in a crisis. I can relate.

Ressentiment – deep hostility combined with powerlessness. The promise of an open world, a generous future, seems rotten. We hate it. It’s failed us. The sheen of that; it keeps nicking us like a pen knife writing sentences on the skin of our hard-worn feet. We can’t even quit the platforms, can we? The implied ‘we’ of a web community is now an absurdity. What have we seen of the Web in thirty years? Unimaginable horrors. Nevertheless, the perambulations continue.

Right now, I’m deeply interested in the dissonance between how we feel the internet ought to be structured, how it almost was, and what it’s become. The dream metaphors we might use for how it once felt to drift between websites, stumbling upon weirdness after weirdness, unlocking more zones of reality. This versus the algorithmic governmentality and corporate monopolies, ‘technofeudalism’ (Varoufakis) and the appification of it all. I think I got interested in poetry right around the time I fell out of love with the internet (2015). I would memorise passages of Charlotte Smith’s sonnets and learn to swoon over Keats. I felt there was something in the shifting stanzas, the intricacies of form, the dazzling surprises it produced and the infuriating difficulties of grasping the source code — a connection.

I still use the term ‘post-internet’ because I want to believe you can take what Tavi Gevinson in 2018 called ‘The utopian ideal of the internet’ and polish its ‘antiquated’ remains. You can still feel the affective charge of every Web-related signifier that has brushed your life. You can be desensitised to ‘internet discourse’ through the media proliferation of tales of digitality, its foreclosures of democracy, its moral flops, its proliferating conspiracies. But there are parts of you irrevocably brought alive by the internet. I am haunted by digital solastalgia. As a child who felt out of place, abjected from the beginning, I sought the Web as a place not for social belonging exactly but something more like beauty, information, elsewhere. I found little pockets of home all over the place. The web (I’ll stop capitalising now and step out of History) was an extension of the fictional landscapes I found in my dreams or when walking around, making up novels in my head which I did every day until I hit puberty and hormones ruined my brain forever (or whatever). I don’t really know where to find those places any more. They weren’t just artefacts and I know this because you can’t produce a screenshot of a website from 2003 and experience a sweet pleasing nostalgia in the way you could with say, a beanie baby. It was something about the world of it all, the navigation, the desire paths forged to get there. The post-internet, for me, is a lifelong quest in understanding that melancholia and homesickness of what comes after. What do I do with the feeling of ‘we can’t go back there, where do we go now?’. All this time, have I used the web itself as some elaborate metaphor for wanting more than a hostile, futile reality? It’s why I like infrastructure, databases, libraries: the promises of systems which take you somewhere. Which transit something. I also love loops, links and non-linearity.

What was the poetry that got me into poetry? It was Romantic in flavour, sometimes in era. Something between the locatedness and dislocatedness, the attention to daily life, the catapulting scale logic of the sublime, the dogged attempt to render the brain on Nature, the melancholy and mourning, the quiet adoringness, the slow accumulation of elements, the sense of quest, pilgrimage, the unexpected visitor at the door. The everpresence of something more mysterious than could easily be folded into waking life. The delicious fug of opium and promise of a language capable of killing pain. The shimmering excess. The imaginative extremities and morbid dullness of Romanticism were necessary supplements to what the web had done for my childhood.

I’ve been dwelling on this quote awhile, from a Spike article about ‘What’s after Post-Internet Art?’:

The technoromantic reimagines posting as liturgy, algorithms as messengers, and artists as saints. They reach into a glorified past for motifs and meaning that invoke the aura of life before memes.Their aesthetic flirtation with the materiality of technology is a double-edged sword, however, that blurs the lines between critique and commodity fetishization. The stakes for this ambivalence are high at a time when capitalist technology is threatening human dignity and agency. Do we really want to engender an emotional attachment to the internet?

Is the function of art to engender the emotional attachment or to transmute its energies into something other? In my day job, I spend almost a whole day a week dealing with academic misconduct cases relating to the plagiarism and hallucinations of Generative-AI. I am supposed to come up with ethical and interesting ways to engage new technology in the classroom, but I fantasise about whole server forms blowing up or quietly being sucked back into the toothpaste tube of Silicon Valley, as if none of this ever happened. At the same time, with two close family members currently undergoing heavy duty cancer treatment, I marvel at the wonders of modern medicine. I think about what Tracey Emin said when asked by Louis Theroux what she thought of AI, or whether there was room for AI art in the world. She says ‘thanks to robots […] that’s another reason why I’m still sitting here’ [presumably due to AI’s role in innovations in cancer treatment and her own recent experience of this]. She’s also like, ‘In terms of art, AI doesn’t really sit well with me, especially when I’m a compulsive, passionate, hot-blooded person who paints’. The contradictions of my feelings about machines get more extreme by the week. I feel born into this contradiction. It’s maybe why my former work twin Nigel would always leave old copies of Wired at my desk.

Does all poetry written after the ‘post-internet moment’ also risk the commodity fetishisation mentioned above? Insofar as it betrays its own lovingness towards the technology it otherwise seeks to critique? Do we want an archness of superior distance or can we do something else with that self-awareness? I think the affect touched upon by Kat Kitay’s piece in Spike is Romantic irony, you know when you realise the narrator is caught up in the situation being described. The Romantic poet speaker discovers they are also a character in the poem. There’s a kind of turn. Timothy Morton uses Blade Runner as a classic example of this, you know when Deckard realises he’s a replicant. Being asked the question, what do you know about the year you were born, for me is like being asked what do you know about what happened to the web? My life is a character in the web’s and the web is a character in my life. What’s the poem here? The continuous mess of everything enmeshed, written, performed, dialogued, deleted, drawn and coded in my lifetime. I have a hot-blooded relationship to the internet. It makes my fucking eyes twitch.

Is transmutation an alternative to merely engendering feeling? I like the word transmutation because I learned it from the great poet Will Alexander. It’s also used by Ariana Reines a lot. We’re thinking here about alchemical transformations in the realm of language, feeling, sensing. I want a poetry that is able to metabolise impossible feelings and in doing so, fuel its reader to think anew. Do I reassign the pain of childhood, the loss of some otherworldly dream, onto the external scapegoat of an enshitified internet? Is that okay? I think about all the times our art teacher made us sit at PCs unconnected to WiFi writing about the design of vintage radios and speaker technology. We had no access to books, the web or other resources to find out more about the designs displayed to us. So in lieu of history or context, we wrote acute, proliferating descriptions of what we saw. What it reminded us of. We found endless vocabularies for edges, colours, surfaces, affordances. This mind-numbing two hours a week was a little oasis from digital supplementarity. A cool, replenishing retreat from external stimulation. We sat on hard, tall stools and typed on clacky keyboards. A tiny little art factory. I had only my brain and the image. I didn’t know it at the time but I was learning that ekphrasis can have a communicative and transformative function. I wrote through the notion of writing about radios to escape the moment where I was supposed to be writing about radios. This did not prepare me for my Art & Design exam so much as it prepared me for poetry.

What do I do with my hatred of the internet? My yearning for it? I write poetry because poetry is a cheap form of that dream architecture I so longed for, all of my life, and I felt good making/using/playing. Marie Buck has a poem that says ‘The point of reading is asynchronous intimacy, and hopefully it works forever’. I said this to my colleague Rodge last week, when we were having one of our regular moments of private despair, and he prints it out and now it’s on the wall of my office. When I look at it I think about all the books out there and all the interesting things I’ve read on the internet and how connected I feel to other worlds. I just have to keep that connection going. I will never know what it’s like to have not been online.