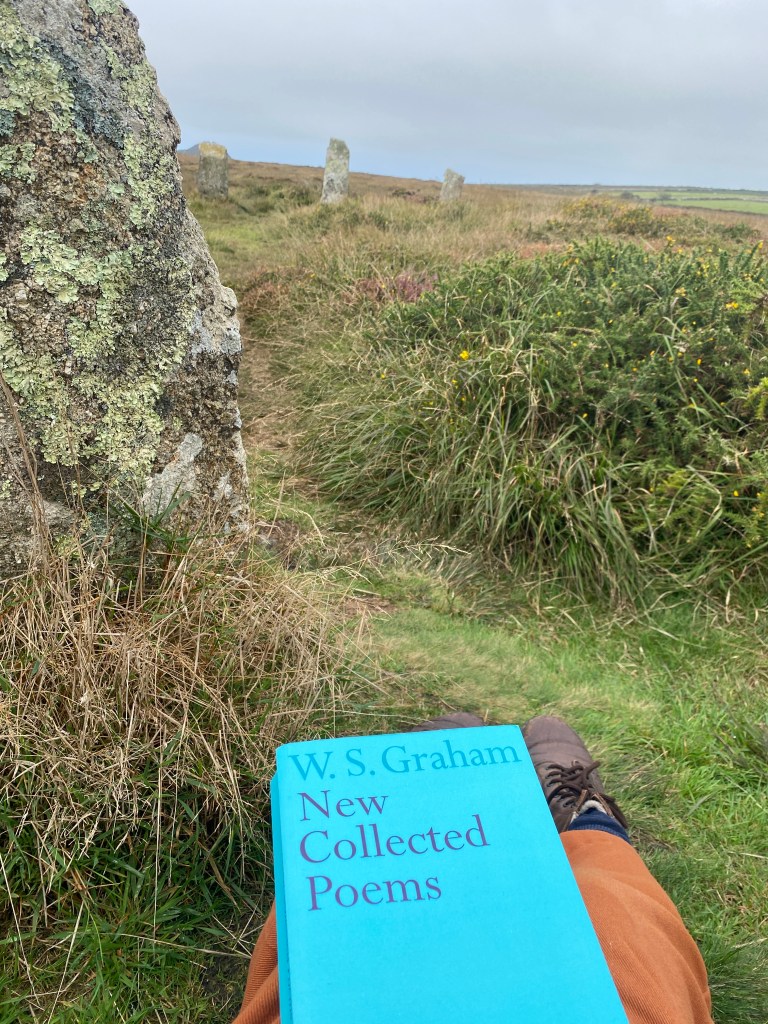

I’m on the twelve-hour CrossCountry from Penzance to Edinburgh. Penzance is the most westerly town in Cornwall and being this close to the edge of something calms me. I always sleep better by the sea. On my way here, on the Great Western Railway, a woman gifted me a glass sculpture with a rainbow inside it, as thanks for helping with her bags at Truro. ‘It’s for stirring your drinks’. For the past week, I’ve been writer in residence at The Grammarsow: a project which brings Scottish poets to Cornwall in the footsteps of WS Graham, who was born in Greenock but spent much of his life down here, making a home of Madron, of Zennor, of the moors. To say this has been a magical week is to say it changed me. I first came across Graham when the poet Dom Hale sent me a voice note of his elegy, ‘Dear Bryan Wynter’, out of the blue; I immediately went out and bought another bright blue, the Faber New Collected Poems. There was something about that foxglove on the wall and the hum of some memory in childhood, watching the bees.

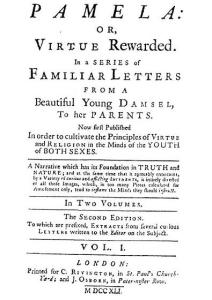

Graham grew up in Greenock, on the Inverclyde estuary. A town where I used to teach writing workshops at the Inverclyde CHCP, taking weekly, then fortnightly trains with our chitty from Glasgow. That time in my life is a blur of shift work, seasonal overhaul, hopeless crushes. I’d get there early to look at the lurid flowers in Morrisons with Kirsty, my co-tutor, or visit the docks alone. Sometimes, I brought my little heartaches to the docks because the air felt smelted, or salt-rinsed, excoriating. The nature of these workshops was that people would share their life stories of such intensity we’d bear them home. I remember one woman writing a story about the moon, ‘we share the same moon’: the one thing connecting her, unconditionally, to her estranged daughter. Many people with stories of recovering from addiction through returning to childhood pursuits: the fishing taught by their fathers, the harbour walks, the musical grammar of language. Graham was trained as an engineer and spent some time on fishing boats, but dedicated most of his life full-time to poetry. The more I learn about this, the more I pine for the shabby romance of that clarity of pursuit. Not as a sacrifice but a great generosity from him, like a penniless rock star.

I’m sure it took a toll on his friends. Graham sent many a letter pleading neighbours and pen pals for the loan of a pound or a pair of boots, once thanking the artist Bryan Wynter for a pair of second-hand trousers. His letters are documents of a life lived in gleaning, bracing the elements, enjoying his wife Nessie’s lentil soup and of course, drinking. On a ‘bleak Spring day’ in 1978, by way of a quiet apology, he pleads with Don Brown, ‘I was flippant in the drink when you came with your news […]. Please let me still be your best friend’. He was often full of fire, a real zeal, taking poetry so seriously but life a strange lark, ‘speak[ing] out of a hole in my leg’. He wrote to his contemporaries — artists such as Ben Nicholson and Peter Lanyon, Edwin Morgan, along with family and friends — with bags of personality, a man self-fashioning in the long blue sea of ‘I miss yous’. As he wrote to Roger Hilton:

We are each, in our own respective ways, blessed or cursed with certain ingredients to help us for good or bad on our ways which we think are our ways. What’s buzzin couzzin? Love thou me? When the idea of the flood had abated a hare pussed in the shaking bell-flowers and prayed to the rainbow through the spider’s web. I have my real fire on. I am on.

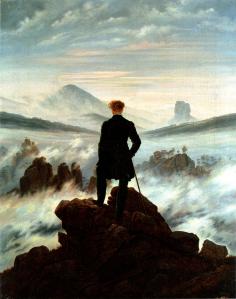

The real fire may have been a woodburner, sure, but it’s something lit within him. The letter as a turning on, turning towards: we see this spirit of openness and address in the poems. The real commitment to Lyric. I love the hare that shakes in the flowers with its rainbow religion. I love the flush of arousal from walking uphill at speed. I saw many a spiderweb and two hares chasing each other on dawn of Thursday. On the train home texting many friends as if to have the rush of being held again, ‘Love thou me?’, could I be so vulnerable. A foxglove shook in the wind. The line as a tremble is lesser felt in the steady verse. Clearly, Graham wasn’t afraid of sincerity, though he always took pains to remind his addressees of his roots. ‘No harder man than me will you possibly encounter’, he assures Hilton; elsewhere, after the death of Wynter, he writes to his Canadian friend Robin Skelton of the coming funeral: ‘Give me a hug across the sea. […] I am not really sentimental. I am as hard as Greenock shipbuilding nails’. In a way, the infrastructure of space inflects the language as its face. I’m reminded of a quote by Wendy Mulford which Fred Carter shared at the recent ASLE-uki conference in Newcastle, where she talks about ‘attempting to work at the language-face’. I wear the face of the land, Graham seems to say, and the build of it. At West Penwith, we face the end of the land, literally Land’s End to our west. It is sometimes a silver gelatine, other times a bright blue, a fog grey thicker than thought. A granite-hard land that nonetheless sparkles. I recall a rock on the beaches of Culzean, in South Ayrshire, we’d come across as kids. Mum called it a ‘moonrock’ or a ‘wishrock’. It was a perfectly huge dinosaur egg of white granite. I find this particular rock showing up in my dreams, even now; as if having touched it, I become complicit in a deep time that doesn’t so much store the past as bear its promise. What could hatch from within a rock like that? What could move it, or hold it?

Graham had the idea of poetry’s ‘constructed space’, what I’d call a lyric architecture for reassembling something sensuous in memory or emergence. That this space isn’t just designed (as in my idea of architecture) but constructed points to that emphasis on building. What kinds of muscle, time, effort of spirit and will go into this? The poet Oli Hazzard writes that one of the effects of Graham’s poetry is ‘that I feel like it allows me—or, creates a space in which it becomes possible—to see or to hear myself’. Graham’s poem ‘The Constructed Space’ opens with the line ‘Meanwhile surely there must be something to say’. I always hear it in the lovely vowels of his Inverclyde accent, assuring. Like he’s sitting with you in the poetry bar, two pints between yous, and the poem gives this permission to talk or make space to listen. I think of Denise Riley’s ‘say something back’. My own need always to blurt, interrupt, muse out loud what mince is in my head. It continues:

[…] at least happy

In a sense here between us whoever

We are.

As I write this, light dances on the opposite wall of my tenement flat and it’s prettier than anything given to me by the window. Sometimes my love says I am harsh when they need delicacy, and so I soften the heather of my voice to listen. It’s true that I was happy while reading that poem, a happiness or lightness in the brain as precarious as the light is. Changeable and easily blown further west to let in what fog, or dimness. I don’t mind my brain when I’m in Graham’s poems. By which I mean, it’s no longer a drag to be conscious or sad; things move again, their metaphors in process. There’s a lightness to quietude, its intimate premise, that holds me. Nothing extreme is promised here, ‘whoever / We are’: lyric address sent through ether to find that ‘you’, held in the future’s new ‘us’. It’s better than a page refresh, reading the poem to think something Bergsonian of the self’s duration. I’m more snowball than the first maria who read this. It’s a kind of exhale, in a sense, like Kele Okereke singing ‘So Here We Are’ from an album named suitably Silent Alarm. Imagining my loves at the same time, out in Stirlingshire lying tripping by the loch, their eyes skyward, the high or low. I cherish that wish you were here / so here we are. I can look out from inside the constructed space of the poem. Wheeeeeeeeesht, you. You’ll find constructed spaces everywhere in Cornwall. The lashing blue skyscapes of Peter Lanyon, the abstract panoramas of Ben Nicholson, the ambient plenitude of Aphex Twin (especially ‘Aisatsana’ and most things from Drukqs). I want ambient or abstract art to give me the clouds in my head back to myself, with the light of it. Colours, gestures, fractals, lines.

~

I’ve spent the past week schlepping around the moors and lanes, reading Sydney Graham’s poems and letters, cooking veg on my wee stove and eating simple marmite and butter sandwiches. I have this grandparent on my mum’s side who shared his name, who died of cancer before I was born. Sydney was the name Graham tended to go by, signing letters. It’s not that I’m looking for literary fathers but I stumble into their charismatic arms all the same. Is it guidance I look for, or perspective? I love the rolling enthusiasm, pedantry and chiding of his letters, as well as their cheekiness and charm. His dedication to writing and reading, his swaggering or boastful tendencies after an especially successful performance (coupled with an irresistible gentleness and warmth). His big sweet expressions ‘THE MILK OF HUMAN KINDNESS IS CONDENSED – TTBB)’, ‘IMPOSSIBLE TALK’. TTBB is the slogan of Grammarsow and a familiar exhortation in Grahamworld, meaning Try To Be Better (the title of an excellent anthology of Graham-inspired poems, edited by Sam Buchan-Watts and Lavinia Singer). I summon my voices, I try to be; used to be; want us to be.

There’s a quietude I love about the work, which suits the land and mind. After a summer of working three paid jobs, and two voluntary, I was ready for a gearshift into something relaxed and focused. I’d had enough of my own ‘impossible talk’. Being here was like being given permission to play and explore. Quickly I realised my time didn’t need to be ‘dedicated’. I lived by the cruising whim of the big sky, its scrolling clouds and moodswings. Saw the moon at two o’clock in the afternoon. I watched dragonflies dart between the lanes, listened to my neighbourly ravens at night. Watched big jenny long-legs make flickery silhouettes on the walls. Slept peacefully with spiders above me and the ravens being craven. I wanted all these things in my poemspace, and the poems themselves were initially scarce, then they began a familiar elongation that was comforting, with the swerves of a bus but also the tread of a walk. Some poems wanting to hide themselves between logs where I might later try and find them.

~

A grammarsow is the Cornish name for a woodlouse, or what we’d call in Scots a slater. I remember growing up and having this internal argument about language: was I to go with what my English mum said, or everyone at school? Aye or nay, yes or no. At some point I realised it wasn’t a question of scarcity and elimination, but abundance. The words became barnacle-stuck from all over the sloshes of life, swears and all, and I cherished their stubbornness. Even those gnarly, uncommon words and spicy portmanteau like ‘haneck’, ‘gadsafuck’, ‘blootered’ and ‘glaikit’. And yous: the juicy, plural form of you. Addressing the crowd, the swarm or many. A woodlouse is a terrestrial crustacean drawn to damp environments. I grew up with woodlice crawling out from under cracked kitchen tiles, unearthing raves of them hidden under rotten logs, finding them in tins of old paintbrushes or sometimes a bag of flour or sugar. I always liked the way their little legs seemed translucent, a little alien, and was especially seduced by their darling tendency to curl up into a ball, for protection, like Derrida’s idea of the poem as hedgehog.

Across the English language, there are many amazing names for the humble woodlouse, not limited to:

- armadillo bug

- billy button

- carpet shrimp

- charlie pig

- cheeselog

- chisel pig

- doodlebug

- hardback

- hobby horse

- hog-louse

- jomit

- menace

- pea bug

- pennysow

- pill bug

- roly-poly

What is this penchant for lists I share with Graham? I want abundance from something other than products. I’m dumbly monolingual and lists are one of the few ways I can accumulate nuances of meaning. My attention-disordered brain collects lists as procrastination for the Thing itself, what is it I should be doing, always on the tip of some other event horizon bleeding through the last and first, so nothing is really finished. I like that in West Penwith, to look at the Atlantic you don’t see any islands, so there doesn’t have to be an end. You have the illusion that there can always be more time. The sea as this list of limitless light, colour shift, unbearable senses of depth. You are here.

~

The grammarsow crops up in Graham’s letters. In a missive to Robin Skelton, he muses:

And what are we now? Maybe better to have been an engine-driver in the steam-age. A sportsman a shaman a drummer a dancer rainmaker farmer smith dyer cooper charcoal-burner politician dog bunsen-burner minister assassin thug bird-watcher poet’s-wife queer painter alcoholic ologist solger sailer candlestick-maker composer madrigalist explorer invalid cowboy kittiwake graamersow slater flea sea-star angel dope dunce dunnick dotteral dafty prophesor genius monster slob starter sea-king prince earl the end.

Again the ‘steam-age’ of other infrastructures interfacing language. Better to have been a wave engineer in the renewable(s) era. I find myself somewhere between the ‘ologist’ and the ‘angel dope’, strung out on critique, measure and the promise of sensuous oblivion. Not sure if the dope is connected to the dunce or angel, but I’ll claim it spiritually as something good: an enhanced performance. As in, those are dope lines I’m reading. Do you want some? ‘And what are we now?’ not who, but what. A question I want always to ask — it’s almost Deleuzian — with someone in my arms or the sea swishing up to waist height, a sea-star clung to the hollows behind my knees. What’s possible when shame is gone. I love tenderly Graham’s list of possible existences and wonder how many I might retrain as (O genius monster), keeping in mind Bernadette Mayer’s old quip that all poets should really be carpenters. I love the raggedness of letters, which is why I love blogs (letters to the idea of being read). Who are they for? We’re so lucky to have these old ones, bound for us, evidence to the material conditions for our wild imaginaries.

~

In Cornwall, I love falling asleep. I love falling for new poems, stumbling a little on the rugged paths, falling for the air and water, for a little more mermaid’s ale or Bell’s, a blackcurrant kombucha or 100g of coconut mushrooms. In his essay for Poetry Foundation, ‘This Horizontal Position’, Oli Hazzard writes about a time Graham ‘went for a walk on Zennor Hill in Cornwall and fell into a bramble bush’. This falling was a repeat pattern: in 1950 he drunkenly fell off a roof and complained of his three-month hospital stay, ‘I hate this horizontal position’. In my DFA thesis I wrote extensively about lying down as a beginning for writing, the horizontal as a form of refusal when it comes to the upright requirements of an assertive ‘I’. It’s no secret that I prefer poetry in the mode of dreamtime, but that’s not to say I’m also a rambler. It’s a poetry of breath and of steps (of vigour!) I enjoy in Graham. Zigzagging and winding down well-trodden moor paths, stumbling upon bridleways that lead around the hills from holy shrines.

I was the lucky poet to first bless a new writer’s cabin that my host, Rebecca, built on some land near the Ding Dong Mine. From the garden, you can see right out over Mount Bay. The skies are huge here. I’ll say that a lot. I saw a seal down by one of the zawns on the north coast, felt the fear of losing the moon in you, let my lips chap on the telepathy of remote secrets. I try to be better, regardless. My poems become languorous obscurities. All of the land has hidden depths.

~

There was a summer before secondary school when we were gifted an unlimited pass to Historic Scotland, meaning our holidays involved camping across Dumfries and Galloway, the Trossachs, the Highlands, in search of abbeys, monasteries, castles and holy sites in various states of decay. I was turned off by leaflets documenting the actual details of history, emerging sleepy-eyed from the car where I’d been navigating the turgid sentences of fantasy novels or playing platform games like Super Mario. There’s a particular form of carsickness that produces electrolytic effects conducive to imaginative ventures. What I mean to say is, instead of vomiting I overlaid the real world with the promise of portals to elsewhere. In Penwith, I walk off my city sickness and sit by the standing stones, quoits and old ruins of industry. What do I imagine but a ‘news of no time’, still to come? Zennor Hill is both poem and place. The more I’m here, the more a sort of aura thickens.

On my last morning, I wake to sunrise over the sea. Dew shimmers the rosehips. The air is earthsweet as ever and I don’t know how I’ll go home. Travelling is an experience of dislocation: here, I find home again in language, its caught habits, Graham’s words sluicing Clydewards. There’s a poise to his poetry, steadfastly composed as ‘verse’ and often by iambic measure. Making perfect prosody with the chug of the train. I was pleased to roll into Glasgow having bumped into my friend Kenny, the whisky god of the Hebrides, attuned to the flight-pulse of conversing again. Hungry, ‘putting this statement into this empty soup tin’ to say cheerio as Sydney would, lighting up poetry to finish it, the best thing of all, a warm scaffold to hold up how we missed each other. A quiet disintegration of cloud. What are we now?

With thanks to Andrew Fentham, David Devanny and Rebecca Althaus for kindness and hospitality. Long live The Grammarsow!