It was the morning I had decided to stop living as if dust wasn’t the primary community in which I sobbed and thrived, daily, towards dying. I spent Tuesday night in a frenzy trying to discern what particular dust or pollen (animal, vegetable, floral) had triggered my allergies anew, what baseline materiality had exploded in my small room its abysmal density. All recommended air filters had sold out online in the midst of other consumers’ presumably asthmatic dust panics; the highly desirable Vax filter seemed sold out across all channels, and I eyed up the pre-owneds of eBay with lust and suspicion, through a fug of beastly sneezes. A friend recommended the insufflation of water as a temporary remedy: ‘I drop some drops on my chopping board, get a straw and snort it up like a line of Colombian snow’, he texts me. I sneeze at the thought, but have to admit that the promise of clearing one’s nasal cavities with water is somewhat appealing. For isn’t water, like sneezing, a force in itself? Some kinds of sneeze come upon you as full-body seizures of will; so that to sneeze repeatedly you must surrender an hour or so, sometimes a full day, to the laconic state of being constantly taken over by this brute, unattractive rupture. ‘Sneezing’, writes Pascal, ‘takes up all the faculties of the soul’. My soul is in credit to the god dusts, who owe me good air. It’s why I am always writing poems (the word air meaning song/composition). But maybe I need good water, a wave of it.

In Syncope: The Philosophy of Rapture (1990), the philosopher Catherine Clément characterises sneezing as an instance of ‘syncope’: a kind of ‘“cerebral eclipse,” so similar to death that it is also called “apparent death”; it resembles its model so closely that there is a risk of never recovering from it’. My muscles ache; I eclipse myself with blood, cellular juices and water. What kind of spiritual exhaustion results from being cast into eclipse repeatedly? Quite simply, one becomes ghost: blocked, momentarily or otherwise, from the light of consciousness. One becomes lunar and attached to the dark bright burn, the trembling red of their inflammation. Those who suffer respiratory allergies might better glimpse what Eugene Thacker calls ‘a world-without-us’. I sneeze myself to extinction. It is the hyperbole of a felt oblivion. I do this on random days of the year, at random times; it is beyond my control. But can I derive pleasure from it, as one does the other varieties of syncope (orgasm, swoon or dance)?

Let me admit, I have always had a fetish for those moments on television and film where a character is administered, or self-administers, an intravenous dose of painkill so sweet as to enunciate this ecstasy simply by falling to a sweet slump, their eyes rolled back accordantly. The premise of silencing the body’s arousal so completely to blissful inertia (suspending the currency of insomnia, hyperactivity, anxiety and attention deficit) is delicious. The calmness of snowfall, as if to swallow the durée of its full soft melt. From quarantine, I fantasise about having adequate boiler pressure as to run a bath and practice the khoratic hold of hot water’s suspension. This is not what I text my landlord.

Recently, my partner spent several hours unpacking boxes from the attic of their parent’s house, in preparation for moving belongings to a new flat. The next day, I found myself suffused in the realm of allergy: unable to think clearly, or articulate more than three words without the domination of a sneeze. On such days, I am held on the tight leash of my own sensitivity: I tremble pathetically, my blood temperature rises; my nose glows reindeer and no amount of fresh air, hydration or sinus clearance will appease it. I am not ‘myself’. The body has enflamed itself upon contact with the ambient and barely visible. I feel an intimate, but non-consensual relation to the ghost trace, the dust trace, of all boxed things — finally been given the attention they so summoned or desired in dormancy. I mourn with objects the passage of time and neglect so betrayed on their surface; I never ask for this, but my body is summoned. Dust presses itself upon you, even as you produce it. I’m scared to touch things because of the dust. What is it but the atmospheric sloughing of something volatile, mortal — the grammatology of our darkest spoiler, telling the story of how bodies are not wholly our own, or forever.

Sneezing disrupts and spoils nice things; it is an allergic response to both luxury and decay. Cheap glitter, rose spores, Yves Saint Laurent. Sneeze sneeze. ‘When a student comes to class wearing perfume’, admits Dodie Bellamy, ‘my nose runs, my eyes tear, I start sneezing; there’s nowhere to move to and I don’t know what to do. When the sick rule the world perfume will be outlawed’. Often I have this reaction too. It prompts a fury in me: Why can’t I have nice things, as I used to? During my undergraduate finals, I developed phantosmia: a condition in which you smell odours that aren’t actually there (olfactory hallucination). Phantosmia is typically triggered by a head injury or upper respiratory infection, inflamed sinuses, temporal lobe seizures, brain tumours or Parkinson’s disease. Often I have tried to conjure some originary trauma which would explain my condition: did some cupboard door viciously slam my head at work (possibly), did I fall over drunk (hm), was I subject to some terrible chest infection or vehement hayfever (often)? Luckily, my phantosmia was a relatively benign and consistent scent: that of an ersatz, fruity perfume. It recalled the pink-tinted Poundland scents I selected as a twelve-year-old to vanquish the horror of body odour raised by the spectre of Physical Education, before graduating to the exotic spices of Charlie Red. I was visited by this scent during intervals of increasing frequency as I served customers at work, cooked or studied; I trained myself to ignore them by pinging a rubber band on my wrist, or plunging my nose into scented oils I kept on my person. Years later they returned at moments of stressful intensity; the same cryptic, sickly smell.

More recently, phantosmia, under the umbrella of a general ‘parosmia’ (abnormality in the sense of smell) is associated with Covid-19. Not long ago I realised I hadn’t been smelling properly for months, despite not testing positive until very recently. Had I, like many others, a ghost Covid that went undetected by symptom or test? Drifting around, deprived of olfactory sense, I felt solidarity with the masses of others in this flattened condition. I eat, but when was the last time I truly enjoyed food? My body doesn’t register hunger like other people’s; unless it is a ritualised mealtime summoned in company, I eat when I get a headache. Pacing around the flat, I plunge my nose again into jars of cinnamon, kimchi, mint tea bags, bulbs of garlic. Certain things cut through the fug: coffee, bleach, shit. I remember a friend, who was born without a sense of smell, telling me long ago that the absence of that sense made her a particularly spicy cook. Often she wouldn’t notice the over-firing of a chilli until her nose started running. What does scent protect us from? What does it proffer? Surely it is the unsung, primal gateway to corporeal desire itself: the gross and indescribable comfort of a lover’s sweaty t-shirt, the waft of woodsmoke from a nearby village, the coruscation of caramelised onion to whet your appetite. Scent is preliminary in the channel of want. Without it, I feel cast adrift into anhedonia. I begin chasing scent. Still, I sneeze.

Dust gathers. Is it yours or mine? Can we really, truly, smell our dust? How does dust manifest as material trace or evidence? In Sophie Collins’ poem ‘Bunny’, taken from the collection Who Is Mary Sue? (2018), the speaker interrogates an unknown woman on the subject of dust:

Where did the dust come from

and how much of it do you have?

When and where did you first notice

the dust? Why didn’t you act sooner?

Why don’t you show me a sample.

Why don’t you have a sample?

Why don’t you take some responsibility?

For yourself, the dust?

It would be perhaps an act of bad naturalisation to read the dust allegorically, or metonymically, as a figure for all kinds of evidence we are expected to produce as survivors of violence and harm. This evidence is to be quantified (‘how much’, ‘a sample’) and accounted for temporally in terms of cause, effect and responsible agency (‘first notice’, ‘act sooner’). The insistent repetition of dust produces a dust cloud: semantic saturation leaves us unable to discern the true ‘meaning’ of the dust. That anaphora of passive aggression, ‘Why don’t you’, coupled with the where, when and why of narrative, insists on a logical explanation for the dust that is apparently not possible. For anyone summoned to account for their trauma, the dust might be a sort of materialised psychic supplement: the particulate matters of cause and effect, unequally distributed and called for. It seems as though the speaker’s aggression, by negation wants to produce the dust while ardently disavowing the premise of its existence. The poem asks: is it possible to have authority over one’s experience when others require this authority to take the form of an account, a story, with appropriate physical corroboration? The more I read the poem, the more ‘dust’ becomes Covid. But it could be many things; dust always is.

‘Bunny’ also reveals the process by which testimony is absorbed into a kind of white noise, a dust storm repugnant to those called upon to listen. As Sara Ahmed puts it in Complaint! (2021), ‘To be heard as complaining is not to be heard. To hear someone as complaining is an effective way of dismissing someone’. Collins’ poem performs the long, grim thread of being told to ‘forget’, bundling us into a claustrophobia whose essence, the speaker implores, is ‘your own / sense of guilt’. Does this not violently imply (from the speaker’s perspective): as producers of dust, we take responsibility, wholly, for what happens to our bodies? I take each question of the poem as a sneeze: it is the only answer I have. I feel compelled to listen.

As she is asked, ‘Why don’t you take some responsibility? / For yourself, the dust?’, the addressee of the poem becomes conflated with the dust itself. I often think of this quote from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963), where erstwhile sweetheart Buddy Willard announces to budding poet Esther Greenwood, ‘a poem is […] A piece of dust’. Poems can be swept away; they are miniscule in the masculine programme of reality. They are stubborn, perhaps, but easily ignored by the strong and healthyy. In ‘Bunny’, the addressee’s own words are nothing but dust, ‘these words, Bunny’: the name ‘Bunny’ hailing something beyond the colloquial term, dust bunny — a ball of dust, fibre and fluff. The invocation of the name a kind of violent summons: you, the very named essence of you, are nothing but words and dust; there is no proof. The more I say the word ‘bunny’ aloud, the more I become aware of a warm and tender presence; this entity who has lived so long in the house of language — under the stairs, on the mantel’s sentence. Bunny, bunny, bunny. Clots in syntax. Dust can be obliquely revealed to all who notice; it coats the surface of everything. It is in the glow of wor(l)dly arrangement, the iterative and disavowed: a kind of ‘paralanguage’ Collins writes of in her nonfiction book small white monkeys (2017):

similar to ours but that is not ours […] when a writer manages — nearly, briefly — to access this paralanguage, we get a glimpse of what could be expressed if we were able to access this other, more frank (but likely bleak, likely barbaric) reality.

Running parallel to, or beneath ‘Bunny’, is the addressee’s reply, or lack of: the dust of her permeable silence, or inability to speak. It catches as a dust bunny in the throat. So how do we speak or listen, when faced with the aporetic knots of a hidden, ‘barbaric’ reality that is glimpsed in various forms of testimony and written expression? ‘Citation too can be hearing’, writes Ahmed. The title of Collins’ poem cites implicitly Selima Hill’s collection Bunny (2001), which she writes of extensively in small white monkeys as a book ‘I am in love with’. This citation opens ‘Bunny’ through a portal to the household of trauma that is Bunny: documenting, as Hill’s back cover describes, ‘the haunted house of adolescence’ where ‘Appearances are always deceptive’ and the speaker is harassed by a ‘predatory lodger’. Attention (and reading between texts) offers us openings, exits, corridors of empathy, solidarity and recognition. Its running in the duration of a poem or conversation might very well relate to the ‘paralanguage’ of which Collins speaks, in the oikos of trauma, grief and counsel. If poems are dust, then to know them — to write them, read them aloud and listen — is to disturb the order of things, one secret speck at a time. But the sight of each speck belies the plume of many.

The morning I tested positive for Covid on a lateral flow, having assumed my respiratory problems were accountable to generalised allergies, I decided to blitz my one-bedroom flat of dust. In the hot panic of realising my cells were now fighting a virus, I vacuumed my carpet and brushed orange cloths over bookshelves. I was really getting into it. Then my hoover began making a petulant, rasping noise. I turned off the power and flipped it upside down. To my horror, in the maw of the hoover’s rotating brush, I saw what can only be described as dust anacondas: huge strings of dense grey matter attached to endless, chunky threads of hair. Urgently donning a face mask, I began teasing these nasty snakes out with a pencil, as clumps of dust emitted from the teeth of the hoover and gathered on my carpet, thickly. All this time I was crying hysterically at the fact of my having Covid less than two weeks before my PhD thesis was due, the hot viral feeling in my head, and of having to deal with the dust of my own flesh prison: the embarrassment, shame and fail of it all, presented illustriously before me.

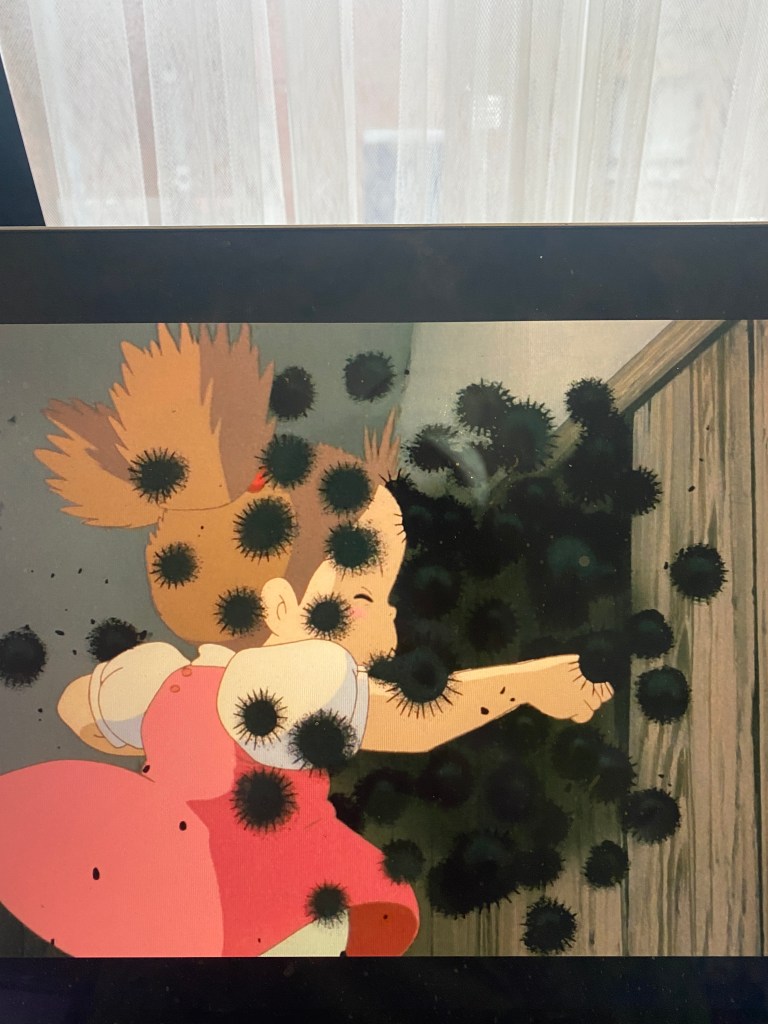

If only I could have purified my air! Forced to confront my body’s invasion (this time coronavirus, not just dust), I try to settle into the ‘load’. I make lists of the smells I miss, research perfumes online (aerosols glimpsed from the safe distance of text). I sneeze a lot, cry a lot, wheeze a lot; and then my sinuses go blank. Is this breathing? I imagine the cells of my body glowing new colours from the Omicron beasties. I re-watch one of my favourite Studio Ghibli movies, My Neighbour Totoro (1988), which features anthropomorphic dust bunnies known as susutarawi, or ‘soot sprites’ (which also appear in Spirited Away (2001)). The girls of Totoro, Noriko and Mei, initially encounter these adorable demon haecceities as ‘dust bunnies’, but later they are explained as ‘soot spreaders’ (as per Netflix’s Japanese-to-English translation). When the younger girl, Mei, gingerly prods her finger into a crack in the wall of the old house she has just moved into, a flurry of the creatures releases itself to the air. She catches one in her hands, and presents it proudly to Granny, a kind elderly neighbour who reassures her the soot sprites will leave if they find agreeable the new inhabitants of their house. When she opens her palms, the sprite is gone, leaving just a smudge.

An absent-presence in My Neighbour Totoro is Noriko and Mei’s mother, Yasuko, who is in hospital, recovering from an unexplained ‘illness in the chest’. Mei’s confrontation with the animated dust mites, or soot sprites, acts out the wound of her mother’s absence. With curiosity and panic, she and her sister delight in the particulate matters of the household, of more-than-human hospitality. What is abject about history then, or even the family, its hauntings, is evoked trans-corporeally through the trace materials of a powdery darkness, dark ecology (see Timothy Morton’s 2016 book of this name) that is spooky but sweet. (S)mothering in the multiple. My sense of smell now is consumed entirely by a kind of offbeat metallic ash; I’m nostalgic for cheap perfume. I’m not sure if this essay is a confession or who is speaking; it seems increasingly that I speak from a cloud of unknowing coronaviruses. And so where do I end or begin, hyperbolically, preparing my pen or straw? The ouroboros of my dust anacondas reminding me that I too was only here, alive and in this flat, by tenancy and to return from my current quarantine having prodded the household spirits for company, with nothing for show for it these days, except these, dust, my words.