(A short story I wrote back in March, knee-deep in Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island, handfuls of Romanticism and longing for the sea. It’s about an oil spill, a young boy’s strange obsessions and his very indulgent Daedalian poetry)

Selkie

He’s become obsessed with making lists of optical properties. Qualities of light quantified on a complex scale he devised at midnight, drunk on a month of insomnia.

His father is very concerned. He comes home and pours amber from the bottle, watching his son pore over homework. Sometimes a storm shatters the sky through the window and they are both oblivious; the father is a terrible farmer. He keeps just a small herd of cows. A local girl comes to do the milking because he is incapable sometimes, and he won lots of money on the races which pays for her wages. He’s grown sick of the jelly-pink udders.

The boy draws lines, draws a series of overlapping ellipses. This is his expression of despair in the face of algebraic equations. He has grown quite fond of receiving those sweet red Fs.

The community is idyllic as any island could be. The school is offshore, on the main island. Every morning, he gets the ferry with the rest of them. They move as one great shoal of fish. Sometimes he watches it happen from afar, the torrent of school uniforms dissolving through the mouth of the big white ship. On such mornings he turns away and walks further inland, hoping to find comfort in the hills.

He never does. It is only the sea he loves.

[…]

Once, the milking girl tried to make a move on him. She used to wear her hair in braids stitched together across her skull, but that day she came in with it long and loose and wavy.

“Will ye not get it in the muck?” the father asked, secretly admiring her golden tresses. She smiled at him. She waited for the boy to come down from his room, eking out time with every pull of the milk. He saw her bent over like that, the hair dripping over her shoulders. He was holding a tattered textbook.

“I love that you read,” she murmured, to no one. The sound was drowned by the cow’s impatient grunt.

“Easy girl,” she said, thwacking its flanks. The boy stood there watching and she mistook that for desire. She turned to look him in the eye, letting the left strap of her top slip down her arm. That one white breast would haunt him forever, like an immature moon. He averted his gaze.

“What do you want?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” he admitted. He sat in the straw, slumped to the floor, and wept. She had never seen someone so pathetic.

He would stand in the shallows of the sea and feel this ache that was deeper than any pain he had ever experienced. It wasn’t pain exactly, but it was a thing that gnawed at his chest, so much sometimes he could hardly breathe. The grey green waters would shlock around his ankles. In the distance they darkened to purple, to wine. His soul was scorched by sunsets. He picked up shells and held them to his ear, listening for the ocean’s distant, groaning radio.

The old woman in the village store told him she sensed his misaligned chakras. She had a bracelet for that, studded with seven power gems.

“You should wear it day and night,” she warned him.

“I have no money.” He studied the trinket with interest. The citrine and carnelian were pretty, but it was the clear quartz and amethyst he liked best. The tiny crackles inside reminded him of waves, preserved in time.

He hung it back up on the stand, alongside the crystal pendants and the celtic knots they sold to tourists.

“I’ll have a postcard instead.”

“A postcard? Who on earth do you have to write to?”

He sat on one of the picnic benches by the shore. The wind kept threatening to blow everything away so he had to pin the card down as he wrote. It was a picture of some white boats against a flaming sundown. Utterly cliché.

Dear mother, he began. What else was there to say?

Sometimes he would walk for an hour right round to the other side of the island. There was a cleft in the rocks you could find for safety at high tide; it was sufficiently above ground to protect one from the flailing salty waters. He would nestle in that cleft and compose lines:

The vitreous lustre of the sea turning starboard

in tidal cycles, an errant moon

throwing zephyrs across the still bright sound.

Oh mariner, how you have travelled

so deep in the blood of the world! I miss

the sense of your stories, sharp as whisky

in bars where the girls did sing: how lovely

is the newborn day! There are precious

few elements as vast as you, I should

dream only of your strange motifs,

a darkening glass against turquoise air.

In the morning I plot

my passage to the mainland, sullied

with the effluvia of island living,

drunk on the salt and the still bright rain.

He would never show his words to a soul. He rolled the thick pages, torn from his father’s ledger, and stuffed them in the empty tubes that once held his teenage posters. The woman in the café served him strong black coffee, and never once asked him why he wasn’t at school. He left her a £1 tip, excess change gleaned from not eating lunch.

Sometimes he would stand on the edge of some cliff and let the wind buffet his body so hard it was perfectly possible that he’d be torn from his mount and hurled to the sea below, stirred up and strangled in its milky swirls.

A week after the milk girl quit, there was a terrible oil spill. Nobody was quite sure who was to blame. People skipped school and work to go down the shore and watch the slow undulations of the oil on the water. It reminded the boy of something oozing in his dreams, a black thick sweat that covered everything. He wrapped his father’s jacket tight around his shoulders. Flecks spattered the silt and shingle the way ink sprayed from a burst pen. They were waiting for experts to arrive.

Some of the islanders wore oilskins or workmen’s gear and went down the next morning to help clean up. The boy had spent half the night on the safety of his favourite rock, watching the oil thicken and coagulate in the shallows. A few birds washed up, unidentifiable. They looked like lumps of hematite, shining in the new full moon. Sometimes the sight of that black shining oil was so much that the boy could hardly breathe.

It was a job that went on for weeks. The oil just kept coming and coming. People from the news arrived with fancy cameras and started interviewing the locals. They said it was one of the worst offshore spillages in a generation. Old folks tutted and blamed the greed of the mainland.

“They might as well have fountains in shopping centres, spraying this stuff around, for all they abuse it.”

The boy kept a diary of the oil. He tried to write about it purely aesthetically. He wanted a thousand words for black, thick, inky, viscous.

The words brought temporary distraction but deep down they sickened him. He longed to put his bare feet in the sea again. His father scorned him for not helping with the clean-up. He had to do double-shifts with the cows, now that the milk girl had quit.

“You lost your chance there my son.”

The boy started stealing his father whisky. He knew where the weak point was in the distillery warehouse. His father left him alone after that, asked no questions.

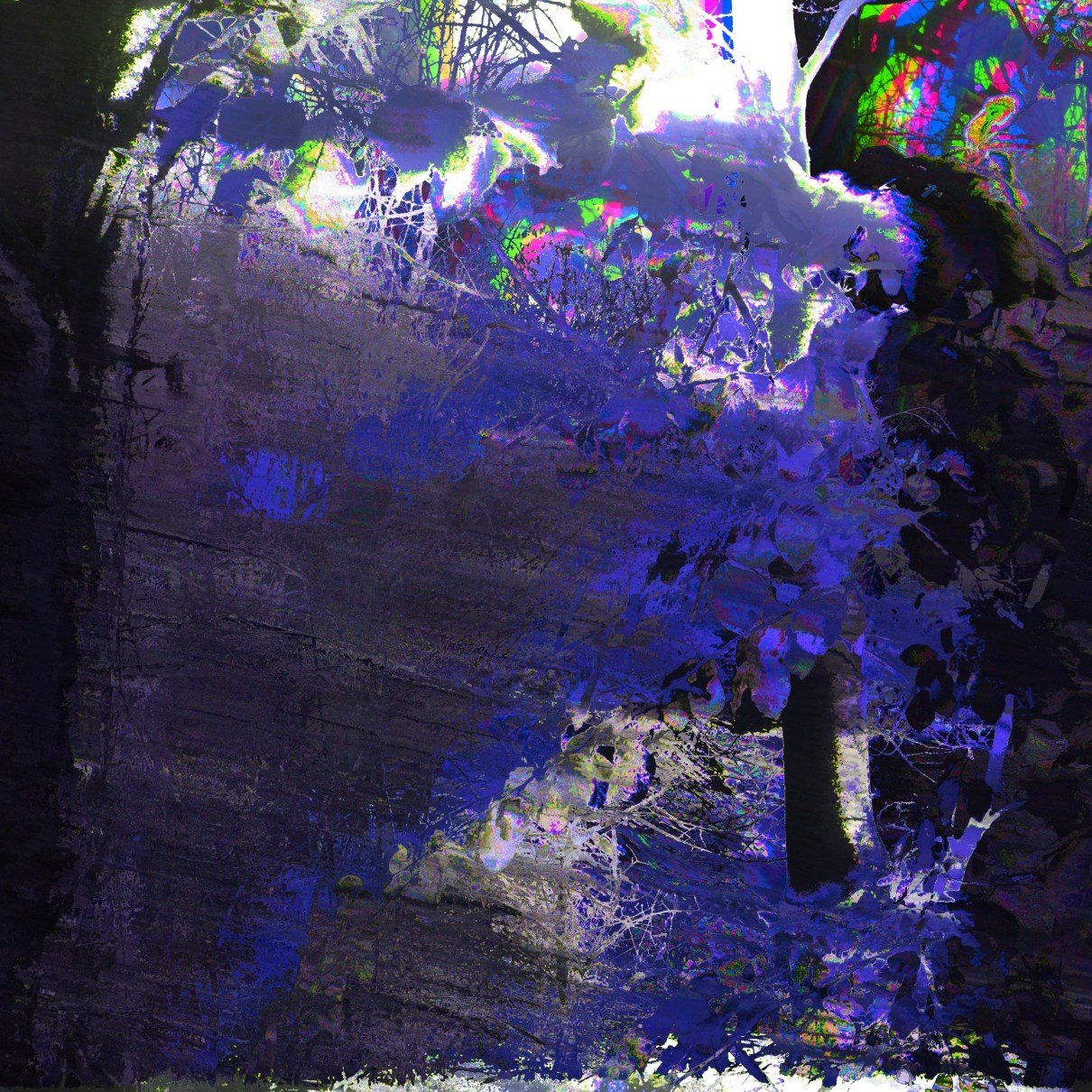

The boy noticed that the light on the island had changed with the coming of the oil. Before, it was all stained glass, watercolour: bright and airy. Greens and blues refracted through each other, sparkling. Now the oil cast strange shadows; there were colours on the beach that the boy could not name. He tried to make sense of them with numerical scales to measure the gradients and shades. He kept his notes in a new journal, whose edges were already curled with dried rain, spattered with sea oil.

The sea reveals its fleshly skin of jade,

the green that makes flickers of the water

shiver among those darkling fish, to fade

inexorably among its daughters,

the girls of the dawn with their wet sea fur.

Five generations have known such deep love

as to carve loud bones from the ocean’s whir,

still spinning the buoys at their broken hulls.

We wait on the rocks for the siren’s call,

laying our bodies to waste on the sound

while the immature moon makes fools of all

who believe in the beautiful, who drowned

Easy as sailors on a summer’s day,

Bloated with salt, time’s lustful decay.

Sometimes his language was so cloying he literally fell violently ill. It was as if he were at sea on a ship, rocked back and forth by a bullying tide. His father found him curled over the toilet.

“Have you been at the whisky my boy?”

“No father. I’m sick at heart.”

“You’re in love?”

“No. It’s the oil.”

He could not eat. He could not sleep. Night melted into day, the hours sat atop one another with the stagnant sense of that oil on the water.

Once, walking along the shore at night, he fancied he saw the milk girl. She walked naked across the sand, her body waxen white, as if carved from the moon. He felt so dreadfully solid in her company. The gooseflesh prickled his neck. She was singing an old song they had learned at school.

From the old things to the new

Keep me traveling along with you

He’d once hated the song, finding it a trite and gooey hymn, but the way she sang it made his heart sting. He realised then that he was no longer a child, that he’d no longer have the innocent luxury of hating something the way he used to hate that song. He thought of the days when he played in the sea until the sun sank behind it, spilling its fiery peach light across the water. How he used to come home with jellyfish stings, salt in his pores, sunburn from the hottest June afternoons.

There was the flaking, turquoise paint on the hulls of abandoned ships. The colour of rust, the old iron chains that oxidised fast in the saline air. The abandoned, unravelled feel of the old yard where the dead ships waited to be repaired. The salt sped everything up, made objects fade eons before they should.

The sea howled. Storms came in quicker than they usually did at this time of year. There was a brief shortage of food as the boats struggled to get offshore, beyond the oil. People were irritable and the cows yielded badly. The boy found a beautiful starfish washed up in a cove. It was jet black, encrusted with oil. It looked like some kind of exotic ornament, worn by a rich lady in a Bond film. He kept it on his windowsill, admired it as the minutes ticked long and slow on the clock.

When the seals started washing up, choked and black and dead as bin-bags, things got serious. Their mouths were bloodied and dry and choked, splayed open as if caught in a final howl. Did seals howl? Could they?

Specialists from the mainland arrived in helicopters to help with the cleanup. There was talk of the island receiving huge subsidies and pay-offs from the petrol company responsible for the spill. Teenagers snapped pictures on their phones and posted them online, tagging them with things like: #shocking #awful #evil #gross #capitalism #darkaesthetic.

The boy realised his peers were wiser than he thought. But they did not know the real damage, the agony he felt sloshing in his chest every time he lay down. There was the sea. It was always there, but once it had been a brilliant cerulean, mottled with orange and heather, grey and jade. Everything smelled of dull and stinking petrol. He wrote in his journal:

It is our world’s first beautiful disturbance. All disasters must entice the eye.

He thought of 9/11, watching the replays on the television screen while his father drank steadily on the sofa beside him.

“There’s evil out there, my boy.”

“But what about the evil in here?” The boy pointed to his own chest. His father laughed.

“I don’t think you’re going to take down buildings any time soon.” Clumsily, he helped his son with his tie. “Now get yourself to school.”

That isn’t what I meant; it isn’t what I meant at all.

Sometimes on the rocky plateaus the remnants of oil ghosted the overflow of water, left swirling patterns of rainbows. He checked the internet and saw that people at school were posting lots of photos again. A girl in his class said she was doing her art project on the oil spill. He wanted to tell her to stop, to tell her she knew nothing about the changing colours and the way time was caught in the turgid undulations.

“Father, when will you tell me about mother?”

“What is there to tell? She left when you were still a babe.”

“But—”

“There’s things you won’t understand til you’re older. Now go and play.”

He had not played for five years. He was old now, he was wiser than anyone thought.

He lugged empty bottles across the road to the dumpsters. He now knew the clinking was conspicuous; he could feel the eyes on his back as he smashed each one through the hole.

Once, he dreamt of the milk girl, lying on one of the hillside fields inland, her hair plaited with cowslips. She was humming a tune because it was his birthday. She drank from a bottle of cherryade, the miniature Barr ones you got from the island store. He saw how her tongue was staining red. He woke up feeling very ashamed.

The raven-dark sea made a fool of me,

those tides of black crashing waves in the night

against the harbour wall. I miss the green

abstracted aqua light, playing so bright

amid those blues, those waters clear as glass

who sheltered the glossy ribbons of fish

to swim in the shimmers, burnished with brass

by an old sun that loves life like a wish.

And now, if I were but a lonesome child

making his way to the soar of the sound

would my young mind find soon such passions wild

inside lagoons, whirlpools, tide patterns bound?

Son to the slippy, cerulean sea,

I rise forward in time to what will be.

When he saw the oil-stained peat of the rocks, the blackened beach, he kept thinking of those towers collapsing. It was like someone had the bright idea of symbolising how everything was falling apart with one fell swoop of a global, terroristic stunt. He asked his teacher if the sea could go on fire, now that it was coated with oil.

“Some folks say that’s the best way to deal with it,” she told him.

“So why haven’t they?”

“I’m sure they have their reasons.” But the boy was sick of not having answers. There were so many creatures out there, wailing with pain beneath the surface, and no one was listening. The ships went out but all they seemed to do was swirl the oil round and round, gathering it thicker. Nothing disappeared. Nothing.

One day, he came home from school to find his father rifling through his papers. While his files were normally organised, shut tight in a drawer, now they were scattered all over his bedroom floor. His father had let a glass of wine spill on the carpet and now a horrid red stain accompanied the places where cigarettes had been stubbed, where coffee had seeped into a forest of fibres.

“What are you doing?” he demanded.

“This stuff, son, what does it all mean?” his father looked at him with tears in his eyes, a sight which struck fear in the boy’s heart. His father only wept on Sabbath days, and even then, only in the early morning when he thought the boy was still asleep. But of course the boy heard him through the walls.

“It means nothing,” the boy said, furious, “absolutely nothing.” He swept up all the papers and slammed the door in his father’s face. That night he would burn the lot, then take a bath in the masses of ashes.

Dear mother, he wrote. He was in the island café and his tea had gone cold. It was three o’clock—the dead time—and the waitress hummed a lonesome song as she swept clean all the tables. He was writing on the back of another postcard. It showed the standing stones, the ones in the centre of the island. He’d only been there a few times.

I don’t know where you are or what happened to you. How many times is it now that I’ve written to you? I wonder if somehow your spirit catches these words from the ether, even as your body is absent from their possibility. I hate myself, I hate my words.

He scribbled out the last line.

I want to get back to you. Father is worse. He drinks like a fish, a seasick sailor. I think he misses the sea more than I do. I think maybe he hates being a farmer, hates the land. Its demands. The sea demands nothing. It doesn’t need fed. But now we’ve fucked up so bad. We’ve poisoned the sea. And maybe you’re out there somewhere watching all of this on TV. The birds are so sticky with oil they lie down without flight and never get up. Some drown. Imagine that, drowning in the black black oil? The feel of it choking in your throat, sickly as molasses. I can’t help feeling it’s somehow my fault. My blood feels poisoned as the sea. Everything is slow and sluggish and heavy. I hardly want to get out of bed. I can hardly breathe.

His handwriting grew increasingly minuscule, so that a passing glance would reveal more a black block of tiny, pressing shapes than actual words. There was something satisfying about seeing all that ink crushed together; it was a bit like the oil itself, taking over the whiteness of the page.

The boy left the café just as it was closing, as the dusk was settling into the sky over the sea. He took the winding path down to the beach, stones crunching beneath his feet. He took a detour to pass by the recycling bins at the end of the street. The café stood alone, its lonesome sign buffeted in high winds and often hurled across the beach, but it wasn’t far from houses. Each one painted a different shade of pastel, to hide the despair of the residents within. The bottle bank, as always, was overflowing. The boy chose a slender, clear bottle, labelled for gin. He picked up a lid from among the street rubble and luckily it fit. Down by the shoreline, he rolled his postcard tight into a tube and posted it through the bottle’s neck. Screwed the cap. Hurled it far out into the waves, where it bobbed for a moment, before the gathering night tides stole it from sight, swirling into darkness, distance.

Her milk-sweet cheeks…

He scratched that one.

The open lungs of the still-breathing sea…

Trackings of light from west to east:

Time co-ordinates; forgotten detritus

Blended mermaid’s purses, lemoning

pale and lovely skeins of flesh

in the gloaming, a moon’s first milk

making cream of an evening,

the curdled settlements of a westerly tide.

My mother, my mother.

Your presence vectoring the harsher

veins of the waves in clearer photons

which press their coastal scars on the canvased

skin of a virtual reality, electromagnetic

stirring of the heart.

There is a scattering, a donut-shaped diagram

shedding the chintz of its skull off

in dullish flakes, blueish as fish food.

(…What are you writing son?

Nothing.

It does pains to lie; come on, show me.

I can’t.

You’re always so far away when you write.

Like mother.

Yes, I suppose…)

I ask father, could the sea go on fire? Like,

if you struck a match to the black black oil?

He said the water was alcoholic, sloshing

with secret poisons, a formula

for ending its own incantatory eloquence

that spreads in the waves such messages

as to embrocate the flow of blood

diseased in the world’s great spleen.

He said nothing of the sort; he was cold

and mean. The tumorous lumps

puffed at the pores of his torso, unfurling

like chanterelles, yellowing the gorse

and scrub of a forest. I knew then

that his pain was utterly edible.

A molten pot of onyx, a knot

shaped like a pretzel, the twisted

wire that snarls in the dark

of his heart. Father,

he was a sailor once,

a man of the deep

black waves.

He remembered the milk girl used to sing to the cows. She cooed at them, sickly sweet, then struck up some old folk melody he recognised from the songs they sang in primary school. Songs about the changing seasons, the inevitable cycles of nature. She knew how to keep the animals still, to tame them to her softening will.

Once, he made eye contact with a seal. He was sitting on a rock on the island’s easterly side, hoping for shelter from the autumn wind. The black shape had rose, dark and smooth, from the choppy grey waves. Its eyes had flashed back at him, uncannily human, green as his own. Green as the sea in the sweetest shallows, made greener still by heaps of seaweed. His fingers brushed the briny rubber, popping the sacs of air. Is it time yet?

In the café again, he was listening to the old waitress as she stood by his table, hands beating powdery flour on her apron. Her accent had thickened over the years, congealing into the island’s broad dialect like salt crystals fattening in the cracks of a cliff.

“They say half the men on this island lost their hearts to the beasts of the sea. I could tell you many stories.”

“My father?”

“Torn asunder, you could say.”

“By whom? A childhood sweetheart?”

(and if the candied dawn brings tastes luxurious…)

“Yer mother, stupid.”

“He still loves her.”

“She found her skin elsewhere. A better fit.”

“Liquid.”

“Yes.” She rolled up her sleeve. He saw how her arms were covered with an elaborate craquelure of scars and burns and etched-in scratches, as if the flesh were readying itself for sloughing off, the mottled pattern of a snakeskin.

Of all the animals in the marble menagerie

I choose you, silvery moon wisps of limestone

streaking the fault-lines

of my sparkling heart, its sacred burial

beneath the midnight billows. Funereal,

sweetening the crumbling aura,

you see underwater, sharp as a seal’s

dilated vision.

The love notes meant nothing, were for no one. Sometimes, he forgot the original purpose of everything. He kept quantitive records of the weather, the changing seasonal light, the pathways of the lighthouse beam as it cut across the bay, endlessly searching. He missed the special quality of innocence that the place had lost after the oil spill. Even with the cleanup, traces of the disaster remained. The sea birds had quit the agonised sea and even the crabs were shrivelled carcasses, washed up on litter-streaked beaches. The council had all but given up, now that corporate control was hardening its narratives of the wreckage.

What if the gin bottle remained, bobbing in one place, the current thickening around it, enriched by the stasis of oil?

the shadowy slosh of gelatinous babble /

like molasses i stretch long and sweet in your mouth /

i imagine the darkness inside you, a sable

annihilating the spill of me /

your gluey skin sticks to me with the tarry promise

of future absence / a terrible,

sickening lubricant

Sometimes, he wrote what he considered to be filthy, erotic poetry, forgetting to dot his i’s.

Everything he wrote brought him closer to the water. He felt his words surrounding him like cloying blots of oil, swimming in his sleep and spreading out through daily reality. His grades plummeted and his soul found solace only at twilight, bearing cold feet to the dusky waters.

He knew the milk girl came out sometimes to watch him. He saw her emanations from across the bay.

The cows were milking very badly. They grunted with inhuman fury whenever the boy’s father tried to draw from those shrunken teats. The boy ate very little and the father even less, chomping his way through stub after stub of cheap cigarettes.

“My gums are sore,” the boy complained.

“Lack of nutrition,” his father replied. He asked for a slice of lemon in his tea at the café. The waitress said fruit was scarce; she’d have to knock on 50p to his bill.

“That’s okay.”

A few nights later, he woke up to a pillow covered in crusted blood. His mouth was the same, darkened with black clots. A gap in his gums. The lost tooth reappeared beneath the sheets, a little white stump of ivory, knotted at its roots with a tangle of red, seaweed sinew.

“Goodness son,” the father said when he saw what had happened. “That’s one of your molars.”

Terrified he would lose the rest of his teeth, the boy ate only liquids, or else the slippery fish they served sometimes as specials at the café, depending on what the men could bring back from the boats, delicate in silver lamé. Sometimes the fish tasted of petrol, but nobody voiced this opinion.

The boy placed his tooth in an old spice jar and hurled it out to sea, an offering. Sometimes he felt the wind whistle through the gap it had left in his mouth.

The rock pools were finally back to a greener colour. Good healthy emerald sea lettuce, the tawny rust of cystaphora, tangles of Neptune’s necklace. Salt crusts formed round the edges. The boy dipped his fingers in to feel the warming water. Was spring coming?

There was the milk girl, ghostly in a tangle of cowslips.

“How are you, it’s been so long?”

I love the seals and the way their skin

is a rippling film of oil, the wrinkles

like sexy black outfits on tv

stretching and spreading for the flesh

of human hungriness.

“These diagrams,” he told her, “chart the changing luminescence of the dying ocean. Tide patterns spread the moon to buttery swirls in different directions. See where this ellipsis meets the horizon’s curve?” But she had no interest in his geometries, his Venn, his equations. She wanted to talk about the people at school, the films you could see on the mainland cinema, the new dress she had made from an old white silk.

“Do you believe in mermaids?” she asked.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Women are not so callous.”

“If you come to the field I can show you my skin.”

“The strawberries will be out soon, a bed-sheet studded with dewdrops of blood.”

“My skin is white. I am white as the moon.”

“I believe sometimes people breathe underwater.”

“You’re so mysterious. You speak like somebody much older. I had an uncle once…”

“I’m not sure I love you.”

“That’s okay.”

He might have gone with her, might have watched as she shed the magnificent white dress, cast it into a crumple like the cape of an angel. He followed the trajectories of her limbs, watching the shadows move in rhythmic repetition against the pale grass, felt vaguely the rubbing of skin like the way it feels to walk barefoot through fresh, juicy mounds of seaweed.

“Do you miss her?”

“Well enough. I know she’s out there somewhere.”

“Is that really enough?”

“Sometimes it’s all there is.”

The island was gifted a grant as compensation for the oil spill. The village was cleaned up and the shopfronts repainted. The rusting boats in the old dock were going to be towed away to make room for new ones.

The boy and the milk girl started playing a game. They would jump off the harbour wall, hand in hand, utterly naked at the darkest point in the night. In the cold black water they would scrabble down as far as they could, holding their breath, waiting for the exhilaration to rush through their blood. They tried to prolong the time before resurfacing, scrabbling for weeds and stones to tug them downwards. Soon, however, the tide buoyed them upwards and they were gasping for air in the midst of pure darkness. A single light from someone’s cottage spilled gold on the water’s surface. The girl’s hair was blonde and the light was gold; everything else was blackness.

Our bodies slippery as bladderwrack

beating the tide in the stillborn black,

a bolt of cold struck deep in the veins

where poisons gather their listless death.

Everything he wrote was awful now. Soured by the thing that had come between him and the milk girl. He slept all day, wrote by twilight, cast his notes to the wind on his least favourite side of the island. The place with the graves, the place where the air was warmly rich with spirits. It unsettled him.

“You’re missing a tooth,” she said once, poking her fingers round his mouth, where the gums were soft and rubbery.

“Yes.” He clamped down hard on her fingers and she yelped, playfully, like a pup. They went back up to the farm and helped out with the milking, so that it was done in triple time and the three of them could have a meal together, big cups of cider and a shared loaf of bread. She sung into the twilight and the men listened in silence.

The boy took down all his diagrams because the milk girl told him they were freaking her out. He wanted her to sleep in his bed but every night she insisted on going down to the harbour. What with the daytime milking and the nighttime swimming, the boy was growing very exhausted.

“What are we trying to prove?” he asked, folding her shining body to his in the moonlight.

“I want to know, I mean, I need to know.”

“Know what?”

“Can we be creatures of the sea?” He thought then of the seal who had stared at him long and hard, like it had known him forever. He shivered.

“Maybe it’s better not to. Then we can just pretend.”

“You miss her, don’t you?”

“Who?”

“Your mother.”

There are different types of orphans. Some are split irrevocably from their origins, by death or neglect. Others are tied to this primal region of their life by a gossamer thread of dreams. The milk girl seemed to have hatched from the sky, on a pure and cloudless night.

One time, they were night-diving down by the harbour and she disappeared. One minute, they were together, tangled in the gruesome depths of the harbour; the next, he could not feel her body at all. All was rock and weed and jellyfish. The tide was high, it had come sloshing up the walls and with it all manner of ocean debris. As the elders always said, the sea hurls back what gets hurled into it.

After swimming around in the churning currents, trying to make out a slender white shape, the boy gave up. He climbed the rusted ladder and promptly vomited onto the concrete, mouthfuls of seawater and silt and evening coffee. Shaking a little, he stood on the edge of the wall, looking for the gold-blonde head of his little seal. Maybe she just swam away from him, following some milky highway of moonlight back to her nebulous origins. But he could not help but think of how she had just vanished, torn away by some invisible current, her body ensnared by terrible kelp.

She never returned, and he realised that nobody noticed that she was gone. When he asked his father about the milk girl’s parents, he said something vaguely ominous and strange about how she was an outsider, “an immigrant to the island’s soil, born from luminous loins.”

Enough of the hoary midnight mist

that tricks me into feeling.

I am old as the sand, a grain

of the past, and I

am willing to die for that.

He found the dead starfish in his room, still crusted black with oil, as if it were a strange piece of jet or coral. He took it down to the beach one evening, when his bones were aching from all the walking he had done lately, scouring the cliffs for signs of the girl. The starfish looked so vulnerable, but in its black outfit seemed completely strange, a being from another world, resplendent in PVC. He returned it to the dark waters, slipping it under the shallow waves, waiting for it to be pulled asunder. He realised then what a fool he had been, to think he could take something from the deep of the sea, even to hold it and love it. The oil had gone and so had the sea’s suspension, now released into a churning, awful hunger, the cycling time and crazy waves that kept the boy awake—night after night, day after day.