Belle & Sebastian are one of those bands that give you a warm, fuzzy and nostalgic feeling. As much as they’re often lazily attributed to the cultural realm of the ‘indie kid’ or the ‘Glasgow hipster’, this neglects the fact of their wider popularity. They are, after all, a band who’ve been around for over 20 years now. I’ve played their tunes in the restaurant where I work and witnessed middle-aged folks who look like they’re off to a Springsteen concert humming along to ‘The Boy With the Arab Strap’. Their songs have popped up on plenty of popular tv shows and films (‘I Don’t Love Anyone’ on Girls, ‘I’m a Cuckoo’ on The Inbetweeners, ‘Piazza, New York Catcher’ in Juno – to name just a handful). Like a sweet, familiar honey, their music just sticks to you, whether you wanna spread it on your toast or not. Sure, they get a lot of hate: their songs are cloying, the singing a bit too saccharine at times, the lyrics silly, the sound the same on each album. I’ve heard them being called ‘beige’ music.

For me, Belle & Sebastian make pastel coloured music. I don’t know, maybe it’s a touch of the old synaesthesia but I’ve always imagined their songs awash in delicate shades of blue and pink, green and yellow and orange – a bit like the colours of sorbet. They’re just the perfect summer band. Some bands it’s easy to have a colour for, or even a texture: Mogwai are deep deep green and black, LCD Soundsystem are bright, shiny white, Mac DeMarco all denim blue and dirty mustard yellow, Kate Bush is a luscious kind of cherry red, Bjork is all the hues of a pearl, Tame Impala are psychedelic greens and blues and oranges, Aphex Twin is ink black, but sometimes yellow, blue or bubblegum pink. In the same vein, Belle & Sebastian to me are all about pastels, sometimes a wee bit brighter but never beige, except when it’s that classy kind of chino beige that you might see paired with a yellow blouse and pink ribbon. I want to be dressed up with a funny hat, a mini skirt and retro sunglasses when I listen to them. Something lilac, a stick of ice lolly. Hell, maybe even rollerblades. I find myself immersed in the stories of the songs; I sort of want to be a character in one of them – a lost twenty-something with her school days long behind her, figuring out how to deal with the world and enjoying living in the city.

Listening to them involves a kind of camaraderie: you’re sharing the world with them, with all the voices of each song’s narrator; sharing Stuart Murdoch’s hazy, romanticised version of Glasgow, the lives of the quirky characters he writes into his lyrics. The musical arrangements in their songs vary between stripped back and fragile, sometimes very much Smiths-influenced (inherently, B&S are an ‘urban’ band, right?), with pretty melodies adorned with piano, acoustic guitar, maybe a bit of bass (‘We Rule the School’, ‘It Could Have Been a Brilliant Career’, ‘Dress Up in You’ – these are some of my favourites), to zany and fun and maybe even lovably chaotic, with some of the earlier songs sporting surf rock guitars (‘La Pastie De La Bourgeoisie’) or (in the early days, Cubase-arranged) electronic numbers (‘Electronic Renaissance’, or, later on, the near seven minute ‘Enter Sylvia Plath’ which frames its tribute to the late great poet inside a Europop epic), as well as the Beatles-influenced ‘chamber pop’ (of which they share the influence mantle with Camera Obscura) – see, for example, The Life Pursuit. Their songs are often self-conscious, writing about the importance of losing yourself in books and songs (the final song of Tigermilk, ‘Mary Jo’, references the fictional book that titles the album’s first song: ‘You’re reading a book, “The State I Am In”’), referencing themselves, other ‘indie’ bands (Arab Strap being the most obvious), creating this whole dreamworld of literary and musical references which itself becomes the fantasy world of the songs. When you listen to them, it’s impossible not to lose yourself slightly to this pastel-saturated universe. It’s not just twee; it’s bittersweet happiness, nostalgia, personal and cultural reflection – they began making music in the 90s, after all. That’s why I smile when I see someone sporting a wee Belle & Sebastian tote bag or t-shirt: you know there’s someone else out there who shares that sweet and silly, slightly sad but hopeful little world.

In a way, they’re a band for the underdogs. They cut their teeth on the Glasgow open mic circuit, with its crowds veering between adoration or ruthless indifference. Every Saturday, under the guise of various band or solo arrangements, Stuart and his pals would appear in the Halt bar on Woodlands Road (sadly it no longer exists) – you can read all about it in bass/guitar player Stuart David’s memoir, In the All-Night Café, which geekily delves into early musical experiments, the songwriting process and all the crazy moments that brought the band together in their formative year. So yeah, it’s worth a read if you’re a B&S fan or even just a musician. It’s important to remember that the band produced and recorded all their early songs (came together, essentially) at Stow College’s now slightly legendary Beatbox course, which at the time was more or less a course that unemployed musicians in the area took to ensure they kept receiving the dole: ‘From what I could tell,’ Stuart writes of his first impression of the course, ‘[Beatbox] was a total shambles. Just scores of unemployed musicians sitting around in a dark, airless labyrinth, doing nothing. […] I wandered around on my own trying to work out what was what, while people scowled at me, or just stared blankly into space. A thick cloud of cigarette smoke pervaded the place, and something about the absence of daylight and the lack of fresh air made me wonder if the place was actually a detention centre set up by the government to incarcerate all the people they’d caught using Social Security benefit as an arts bursary’ (In the All-Night Cafe, pp. 10-11). This is probably an impression of college hallways and classrooms that most young adults of Generation X or millennials growing up in Britain can relate to: the flickering strip lighting, the apathy amongst both staff and pupils, the sense of suffocating bureaucracy, of life in suspension. And yet out of that dark and maybe even Kafkaesque environment, sometimes the magic happens. People come together and make the best of things – it’s inspiring.

For me, it’s also inspiring that Stuart Murdoch is actually from Ayr. The only other celebrated artist I can think of off the top of my head that hails from Ayr is none other than Robert Burns, so yeah, it’s been awhile since the place has been put on the map, artistically speaking. Belle & Sebastian are usually associated with Glasgow (especially the West End), but for me it’s important to remember their humble beginnings. Ayr still has a pretty cool music scene in terms of acoustic nights in local pubs, but there’s definitely a dearth of actual decent gig venues, especially when it’s producing so many talented musicians through, for example, the well-respected Commercial Music course at the UWS Ayr Campus (see for example Bella and the Bear and the wonderful Shanine Gallagher).

ANYWAY, back to Belle & Sebastian. I wanted to talk about Tigermilk as an example of their oeuvre in general – as the raw, often forgotten diamond. It’s their debut album, though I actually came to B&S first through If You’re Feeling Sinister, having picked it up from Fopp when I moved to the West End for university and decided a B&S CD was a good way of immersing myself in local culture. Tigermilk reminds me of that lost and lonely summer feeling, walking around the city killing time before going to work, worrying about all the books I had to read before September, the people and things and memories I was in love with, that paranoid and desperate desire to write myself and indeed keep writing. It’s a lo-fi sort of album; it feels sweet and magical in that simple way, and you can tell that it marks the moment when the band discovered they had something special going on.

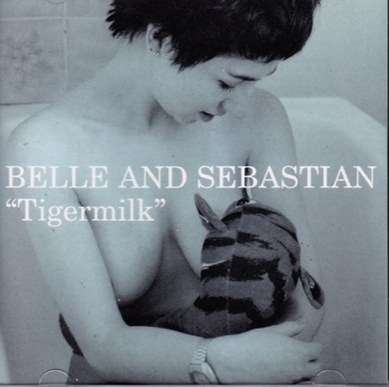

Sometimes the lyrics are a wee bit strange and surreal; the cast of characters Murdoch evokes in his lyrics can be pretty bewildering. The band’s slightly surreal vibe is indicated by the cover art for Tigermilk: a black-and-white picture of Murdoch’s then girlfriend, Joanne Kenney, apparently breastfeeding a toy tiger. Then take a look at the lyrics to ‘My Wandering Days are Over’ for example: ‘Six months on, the winter’s gone / The disenchanted pony / Left the town with the circus boy / The circus boy got lonely / It’s summer, and it’s sister song’s / Been written for the lonely / The circus boy is feeling melancholy’. You’re never sure if the characters are metaphors for existentially pained middle-class indie kids (lost in the job market/lost in the adult world circus of mad capitalism??), or actual protagonists in B&S’s musical universe. That’s the poetry of it – you get to decide. It all sort of makes sense, this girl with spiky black hair nourishing a toy tiger; sure, you can take it as symbolic, but it’s also just intriguing and slightly controversial enough to draw attention to a debut album.

One of B&S’s unique selling points is the whimsical fictions they weave through their ‘brand’ as a band. Take, for example, the sleeve notes to Tigermilk: they detail a cute little tale about Sebastian and Isabelle, the namesakes for the band.

Sebastian met Isabelle outside the Hillhead Underground Station, in Glasgow. Belle harassed Sebastian, but it was lucky for him that she did. She was very nice and funny, and sang very sweetly. Sebastian was not to know this, however. Sebastian was melancholy.

He had placed an advert in the local supermarket. He was looking for musicians. Belle saw him do it. That’s why she wanted to meet him. She marched straight up to him unannounced and said, ‘Hey you!’ She asked him to teach her to play the guitar. Sebastian doubted he could teach her anything, but he admired her energy, so he said ‘Yes’.

It was strange. Sebastian had just decided to become a one-man band. It is always when you least expect it that something happens. Sebastian had befriended a fox because he didn’t expect to have any new friends for a while. He still loved the fox, although he had a new distraction. Suddenly he was writing many new songs. Sebastian wrote all of his best songs in 1995. In fact, most of his best songs have the words ‘Nineteen Ninety-five’ in them. It bothered him a little. What will happen in 1996?

They worked on the songs in Belle’s house. Belle lived with her parents, and they were rich enough to have a piano. It was in a room by itself at the back of the house, overlooking the garden. This was where Belle taught Sebastian to put on mascara. If Belle’s mum had known this, she would not have been happy. She was paying for the guitar lessons. The lessons gave Sebastian’s life some structure. He went to the barber’s to get a haircut.

Belle and Sebastian are not snogging. Sometimes they hold hands, but that is only a display of public solidarity. Sebastian thinks Belle ‘kicks with the other foot’. Sebastian is wrong, but then Sebastian can never see further than the next tragic ballad. It is lucky that Belle has a popular taste in music. She is the cheese to his dill pickle.

Belle and Sebastian do not care much for material goods. But then neither Belle nor Sebastian has ever had to worry about where the next meal is coming from. Belle’s most recent song is called Rag Day. Sebastian’s is called The Fox In The Snow. They once stayed in their favourite caf’ for three solid days to recruit a band. Have you ever seen The Magnificent Seven? It was like that, only more tedious. They gained a lot of weight, and made a few enemies of waitresses.

Belle is sitting highers in college. She didn’t listen the first time round. Sebastian is older than he looks. He is odder than he looks too. But he has a good heart. And he looks out for Belle, although she doesn’t need it. If he didn’t play music, he would be a bus driver or be unemployed. Probably unemployed. Belle could do anything. Good looks will always open doors for a girl.

You’ve got it all here: the playful and ultra twee imagery ‘(she is the cheese to his dill pickle’), the hint of queer culture and crossdressing that sometimes runs through B&S songs (‘This was where Belle taught Sebastian to put on mascara’), the DIY elements, the spatial immersion in Glasgow’s West End as a kind of leafy wonderland where people own pianos in airy rooms overlooking gardens. It’s honest and cute and totally unashamed, totally uninterested in being cool. Compared with the stylised, rock’n’roll swagger of Britpop, this album (originally released in 1996 then rereleased in 1999) is so refreshing. The tale of Belle and Sebastian is a short story, more than an explanation of the album’s lyrics or ‘concept’; it’s a bit ambiguous, a touchstone for all the other B&S characters who populate later LP – it’s perhaps, most importantly, an indication of the band’s consistent literary bent.

‘Sebastian was melancholy’. Well, melancholy is probably the overriding emotion on Tigermilk. Melancholy being that feeling of sadness, yearning and inexplicable loss. An indulgent feeling, a languid and probably narcissistic feeling that is almost pleasurable despite lolling around in the negative. Freud, in Mourning and Melancholia (1915[17]) famously distinguishes mourning and melancholia thus: ‘In mourning the world has become impoverished and empty, during melancholia, it is the ego itself’. Mourning is about the loss of a specific object, whereas melancholia is a vaguer feeling, a depression with no apparent or obvious source, a swallowing up of selfhood into narcissistic darkness. One of the reason’s I really like ‘I Don’t Love Anyone’ is its in-your-face rejection of the Coca Cola style let’s-all-hold-hands-and-be-happy version of love, the assertion of personal endurance and the often denigrated value of independence in a world where we’re all supposed to follow the crowd: ‘But if there’s one thing that I learned when I was still a child / It’s to take a hiding / Yeah if there’s one thing that I learned when I was still at school / It’s to be alone’. I was that kid who sometimes liked to walk around the playground alone, making up stories in my head – adults just assume it’s because you’re being bullied but there’s a golden value to imagination and it’s easier to forget that as an adult, easy to forget that sometimes you need time out from your friends to be in your own mind.

A lot of Tigermilk is about trying to negotiate personal identity in an often problematic adult world with few opportunities for anyone vaguely creative. It’s worth quoting a hearty chunk of ‘Expectations’ to demonstrate this:

Monday morning wake up knowing that you’ve got to go to school

Tell your mum what to expect, she says it’s right out of the blue

Do you want to work in Debenham’s, because that’s what they expect

Start in Lingerie, and Doris is your supervisor

And the head said that you always were a queer one from the start

For careers you say you went to be remembered for your art

Your obsession gets you known throughout the school for being strange

Making life-size models of the Velvet Underground in clay

In the queue for lunch they take the piss, you’ve got no appetite

And the rumour is you never go with boys and you are tight

So they jab you with a fork, you drop the tray and go berserk

While your cleaning up the mess the teacher’s looking up your skirt

We’ve all known (or been ourselves!) the weird kid obsessed with music, inviting abuse with every strange word spoken. Wear something black, a bit of eyeliner and you’re inviting folk to ask you if you “shag dead folk”. There’s always the one of many that has a whole collection of cool things to say, to contribute to the world, but ends up in retail, in a call-centre, maybe waitressing. Again, Belle & Sebastian are the band of the underdog, the folk (and there are a lot of them) who slog away at day jobs but don’t give up on their dreams – whether those dreams involve becoming a star of track and field, a model, artist, musician, writer.

Tigermilk, then, isn’t just a melancholy album; there are some feel good moments, such as ‘You’re Just a Baby’, which features handclaps and a nice rock’n’roll beat with a simple, serenading refrain: ‘You’re just a baby, baby girl’. Fundamentally, Belle & Sebastian are a pop band, and a damn good one at that. Stuart Murdoch recently wrote and directed his own film, God Help the Girl, which more or less demonstrates his near-religious philosophy of pop music, as the character James (fittingly played by the singer from pop/electronic band Years & Years) proclaims:

A man needs only write one genius song, one song that lives forever in the hearts of the populous to make him forever divine. […] Many women and men have lived empty, wasted lives in attics trying to write classic pop songs. What they don’t realise is it’s not for them to decide. It’s God. Or, the god of music. Or, the part of God that concerns Himself with music.

This is some fairly interesting religious imagery coming from a singer (Murdoch) who has always been openly Christian. And of course, the hyperbolic emphasis on music’s divine significance here is perhaps a cheeky dig at the ego of the pop star, but it also touches on the importance of universalism for pop. It’s easy to consume, it should transcend generations, it should be technically perfect – the satisfying work of a ‘genius’. But good pop, as Belle & Sebastian demonstrate, isn’t all bubblegum songs about loving your sweetheart – it also has that spark of something else. For me, B&S capture a very specific experience of existential bewilderment in the modern world, combined with the right amount of romance, comedy, storytelling and a healthy streak of cynicism. God Help the Girl is twee as hell, but it’s also a loving portrait of Glasgow, of the early days of being in a band, the freedom of summer days drifting down the canal with the world shining bright around you. It’s maybe also a portrait of unrequited love. And, crucially, it transforms that cliche, the power of music, into something sparkly and fun as well as serious and uplifting – it is a musical after all. Its ambiguous ending, with the heroine (significantly called Eve – more religious imagery!) finally leaving the city and on a train ride to London where she intends to try and make it ‘alone’ after her existential rebirth and artistic awakening in Glasgow, is perhaps its strongest point – it’s a feminist assertion of personal creative desire as opposed to remaining tied down to the things your friends want.

Once again, Murdoch puts complete faith in his slightly damaged protagonists; he encourages us to just trust our creativity. Maybe that’s why I love Belle & Sebastian so much, because sure, their songs are mostly golden, pastel-hazed pop, but it’s not that simple; they embrace that wavering, magical and sad place between warm dreams and cold reality, and represent all the poor souls who live there in that limbo, such as the eponymous heroine from ‘Mary Jo’: ‘Your life is never dull in your dreams / A pity that it never seems to work the way you see it’. And even though such songs are full of melancholy, you’re still treated, as in an Arctic Monkeys song, to some brilliant lyrical candy: ‘Cause what you want is a cigarette / And a thespian with a caravanette in Hull’. So maybe that’s the special element, the thing that makes the everyday divine, that elevates the ordinary into a valid subject for pop music. And maybe, pleb that I am at heart, that’s why I love it.