So delighted to have been picked as a runner-up in the 2016 GUCW Summer Short Story Competition. The theme was ‘journeys’ and you can read the other winners HERE. Here’s my wee story, about an elderly lady trying to get to the end of the road…

Oranges for Marmalade

“No, no, no, must get to the shop, can’t stop, can’t stop…”

You could only hear her if you were very close to her. From afar, there was only the distant rustle of her words, softly murmuring like an insect.

“Must get to the shop, must…”

You could see her fuss with the door of her bungalow, shuffling along the path out of the front garden and onto the pavement, never forgetting to close the gate. She was always careful with these details. Sometimes the cat was out, draped over the stump of wood where once there was a lilac tree, prowling around the unkempt lawn, or else sitting at the window, watching carefully as her mistress slowly made her way down the road.

It was a beautiful street, even by the city’s standards: a long, broad avenue of horse chestnuts, which shadowed the pavements and when the sun shone they cast dapples of green light on the concrete, clear and pretty as stained glass windows. In the autumn, conkers would gather in the ground, brown and gleaming amidst the fallen leaves, and the neighbourhood children came out in their droves to pilfer them. She had lived on this street for a very long time. Whole families had come and gone, homes were split into rented apartments, townhouses halved into bungalows. Only the corner shop remained at the end of the road, though it had changed hands a few times.

If you watched her for long enough, you would see the rhythm of her walking was most unusual. She stopped in fits and starts. She would halt in her step, standing as if suddenly finding herself tied to the ground, looking around her with a bewildered expression. If you were close enough, you could hear her tutting under her breath.

“Can’t stop, can’t stop.”

She attempted her stilted, aborted journey almost every day. So sad, she always seemed, picking her footsteps over the same old concrete. There was a frown on her face, etched deep into her skin. Her eyes, a watery green, always glazed over, or else were sharp and jolted and fearful.

This is the tree, the special tree which she stops at halfway on her journey. She knows there is something significant about the tree. Her fingers, sometimes, escape the cloak of their gloves and feel along the trunk; dry, brittle skin brushing upon the gnarled wood, whose bark came apart in dusty flakes. Somewhere on the tree two letters are carved: E + J. She winds her pointy finger up the J to where it stops. Sometimes, the sticky sap clings to her nail and later, in the shower perhaps, she will notice it and worry about where it came from.

Was this it? No. She is not here for the tree. She is never travelling towards the tree; it just so happens that she finds herself here again.

She always gets to a certain point in the walk where suddenly everything loses its clarity. She can no longer make sense of the shapes and colours. She does not recognise this street at all. Where am I? Where am I? The windows of buildings seem to stare down at her in mockery, circle-shaped and evil. She is running back through her memory, names and faces, names and faces and places. The East End street where her grandmother lived. Was it just like this? She remembers the ochre and gold of the bricks and the white window frames and the old men that would stand on street corners, at all hours of the day, staring aimlessly and smoking cigarettes.

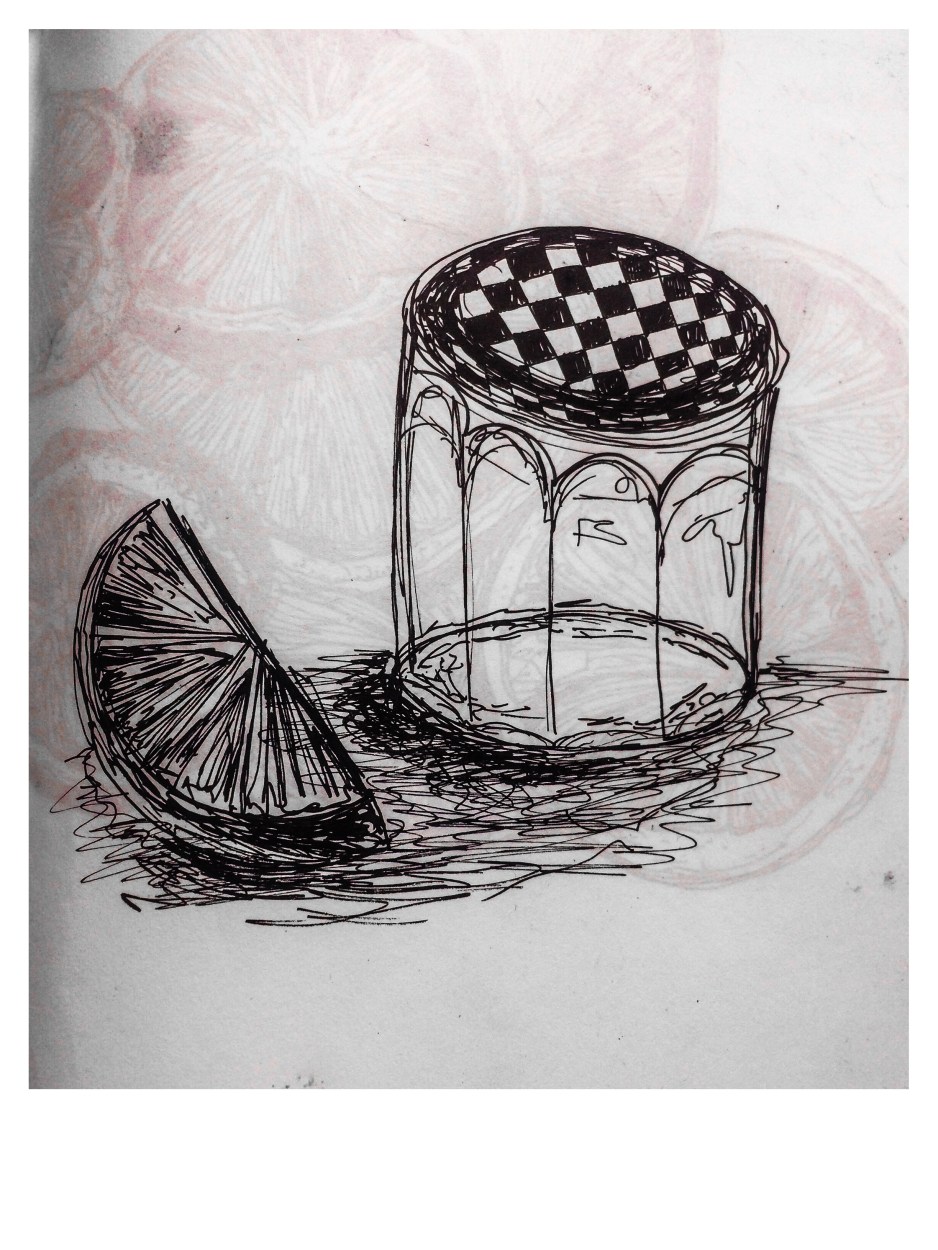

Pull your stockings up, her mother used to scold. She would run around the streets, shooting marbles and playing with the boys, her stockings always half up, half down. She remembers them fondly, those stockings, the colour of a lilac sky, as her father used to joke. He was a secret poet, and he liked to mix words like his wife would mix the oranges and sugar for marmalade. Marmalade, her speciality, the milk of summer nourishment. The fruit comes all the way from Spain, as her father would say, slathering it over his toast. She remembers him reading the newspaper, stealing mischievous glances with butter-smeared lips as she mended the holes in her school blouses.

The sky was greying now, the weather turning. An umbrella: she should have brought an umbrella. The door to her bungalow was so far away now; there could be no turning back. She felt the panic rise like a sickness in her chest. Nobody could know how much she needed to urinate. There was a new desperation to her journey, as if somehow it was now life-threatening.

“Are you okay ma’am?” the woman in the business suit stops her car, rolls down the window. The woman leans her head out but she is already walking away, pacing in circles of confusion. “Are you lost?”

“What? What?”

“I said, are you lost?”

“No, no, mustn’t stop, got to get to the shop.”

“Can I give you a lift?”

“No, no, it’s not far – the end of the road.”

“Are you sure? It’s no bother for me.”

“I must – must get to the end of the road. Good day to you.” She clutches her handbag tight to her chest, thinking how nosy people were, even these days. The car trundles reluctantly away and the street is quiet again. Very few commuters pass through here. It was only the locals who brought their cars to reside in the sleepy parking spots, draped with the luxuriant leaves of the chestnut trees.

There was something she had to get from the shop. What was it? She had lost it again, the slip of paper that she was supposed to carry around to help her remember.

“Something to get from the shop,” she mutters. A handful of kids, skiving from school, burst round the corner, their skateboards cracking loudly on the concrete like fireworks. She shivers with fright, looking up to the sky for an explanation. The kids whirl past her, laughing. They went from one end of the street and onto the next in less than a minute.

Her own children–how old were they now?

“Oh, hello Rosie,” she said once, greeting the little boy who was dragged into the living room by his harassed mother.

“Mum, it’s Robert. Robbie. Your grandson.”

“Robert? Oh, yes, a boy! Hello Robbie.” It happened every time. Every time it was like she was meeting them anew.

“Yes, this is Robbie, Mum,” she repeated, “Rosie’s…dead. Your daughter Rosie, she died out in Israel. Five years ago. Remember?”

“Rosie? Rosie what?” The same thing, every time. She died, she died. “What was she doing in, in Israel?” Sometimes the words would come back to her: It’s just something I have to do Mum, I have to find myself. What was it they had told her? Something about the desert, the collapsed sand dunes, all those foreign-sounding names that had swirled around in her head, loose and dead as the leaves picked up in an autumn breeze. The young folk, why was it they had to go away, what was it they thought they would find elsewhere?

There were always funerals. Funerals were as sure as the passing seasons. People were always dying; that was true enough. You put on a good spread and said your good will and life went on just the same.

“But my Rosie? How…my Rosie?”

“She was stranded, Mum, stranded. My sister and they flew her home in a box.” And her own daughter then, choking up in the living room, white knuckles rubbing her knees.

Stranded, stranded…

Stranded, like she was now, stuck on a traffic island in the middle of this suburban avenue where she had lived for twenty years, and the traffic coming and going so slow and intermittent, and still the thought of crossing terrified her and she was suddenly frozen and her hands were quivering like, like birds’ wings and she knew, she just knew there was someone in the window opposite watching her…

They had given her a necklace with a plastic button, an alarm that she was supposed to press when she needed help. She could picture it, hanging by the door, clicking against the glass as the draft blew in.

She could hear the buzz of a telephone.

The cry of the magpies outside her window.

The sound of her girls, laughing in the garden.

The thrum of the music from next-door.

The skateboards smashing the concrete.

It was all this deep, dark, churning cacophony. She knew she needed to keep moving, but her legs were stiffening, her joints seizing up, her bladder trembling. The rain was coming down now in cold speckles on her face.

Nobody in the street could know the secret strain of her journey. Each time she tried to cross the road, she saw her feet step off over a cliff and the car like a gush of coastal wind, ready to sweep her down to her death. All around her, this sea of sound, lashing and stirring.

She’d always thought of death as a kind of quiet, a restful transition from life into sleep. This was not death at all, this turmoil. The huge green chestnut leaves which bore upon her like so many hands, glinting wickedly with unforgiving light. The clouds clearing, then closing in again.

Her own daughter, and all the things she would have shown her. The special rules that kept families together, the various arts of living and loving and housekeeping. The things that you were supposed to be proud of. The little efforts to make everyday life somehow tangible, meaningful.

She’s left the stove on again.

Often, these days, she thought of herself in that anonymous third person.

She lost her glasses. Lost the handset for the telephone.

That anonymous third person, disorientated, mocking.

Life seemed more and more a journey in which you found yourself lost. You were not supposed to reach a destination, but merely immerse yourself in further confusion. The thought of it was almost a comfort.

She is less distressed. She is breathing properly and her hands stop shaking as she stuffs them in her pockets. As always, it is at this point in the road that she turns back, heads towards the house with the gate and the cat and the alarm by the window and the bathroom with the toilet and the living room where they told her that Rosie had died. It is always at this point that she gives up.

It is only later, at some unfixed time in the middle of the night, that she will wake up and remember the purpose of her journey. Maybe she is dreaming of her mother, sad and milky swollen dreams. Maybe she is dreaming of the quiet suburban street itself: the swaying leaves of the horse-chestnut trees, the conkers in autumn gleaming, the children on the green and the thrash of the skateboards and the way the world looked ten, twenty years ago, before she started forgetting…

Maybe she dreams of her own daughters, golden on the front lawn, singing and playing.

Always she awakes to that singular purpose, a child again, the glitch in her memory that always sticks like a scratch on a record: Oranges. I must buy oranges, to make marmalade. Oranges for marmalade.