So Long, Marianne

(a story I wrote back in April, after a friend gave me two prompts: ‘railcard’ and ‘lonely’).

She found the railcard lying in a puddle. It was the case that caught her eye: its plastic glitter coating blinded her momentarily as she waited to cross the road. A single beam of sunlight had caught that glitter and Amanda knew it was for a reason. She knelt down to pick it up, wiping it clean on her jeans. The man standing next to her on the pavement eyed her warily as she examined it. The name on the card was Marianne Holbrook, and the picture, slightly blurred, showed a girl of Amanda’s age, with cropped brown hair and eyes rimmed thick with kohl and shadow, lips a deep rich red. On the flip side of the case was another card: a student ID, whose expiry date was last year.

“You should hand that in you know,” the man beside her said, interrupting her reverie.

“Yes,” she replied.

Amanda did not hand it in. She took it home with her and tried to go about her evening as normal. She put it up high on her bookshelf, next to the little cat ornaments her grandmother had given her as a child. She put the radio on, to make the flat seem less quiet. She boiled the kettle. She stood in front of the mirror, brushing her long thick hair. The jangly pop music seemed only to ricochet off the silence, intensifying instead of subduing it. Amanda tugged and tugged at her hair but she could not get the knots out. Tears of frustration sprung to her eyes.

She felt pathetic for crying. Her arms crumbled to her sides and she threw down the brush. The kettle began to whistle. Amanda burnt her tongue on the first sip of tea. She checked her phone but there were no texts; there had been nothing, now, for three days.

The following morning, she went out on her lunch break and got a standby appointment with a hairdresser near her work.

“I want it very short,” she said carefully, fingering the long strands of hair that framed her face.

“How short?” The stylist asked, lifting clumps from the lengths of Amanda’s hair and letting them fall again, as if she were trying to gauge how much her tresses weighed.

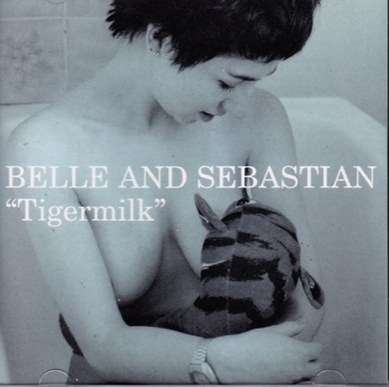

“Oh, a crop. A pixie cut.”

“Bold, huh?”

“Like Laura Marling. Very short.”

“I don’t know who that is honey. You sure you have the features for something that short? I’m not saying you have a big nose or anything but wouldn’t you like to look at—”

“No,” Amanda said firmly, “I want a crop. Please. I don’t care about dainty features.”

“Okay, whatever you want.”

It took an hour. Great wads of hair fell away past her shoulders as the stylist attacked Amanda’s locks with her scissors. She cut away in steady, hungry snips until all that was left was a ruffled mess, short as a boy’s.

“Don’t worry,” the stylist assured her, “it’ll look weird until I’ve wetted it and done the layers.” Another half hour and it was done. The blow-dry took minutes. Amanda blinked in the mirror and tried to imagine what she would look like with heavier eye makeup. Marianne Holbrook. The girl in the railcard photo, blankly staring, mysterious.

“Thanks.”

“It does look rather amazing,” the stylist admitted, surprised.

Amanda went back to work and everyone was so shocked at what she had done that they all forgot to reprimand her for being late.

“Very sexy,” her boss said, biting his pencil. Amanda felt hollow inside as she sat down at her desk. The afternoon stretched before her, empty and dark as an elevator shaft. She couldn’t wait to get home; there were things to be done.

That night, she took the glitter wallet off the shelf and carefully pulled out the two cards inside. She took the student ID and held it over the bin as she snipped it into pieces. The girl in the photo looked very young: she had shoulder-length hair, blonde, a shock of fringe and a lurid shade of lipstick. It hardly seemed the same Marianne as the one in the railcard photo. Amanda turned the railcard over in her fingers. She had looked it up online and discovered that it granted the user unlimited free travel to any UK rail destination. It was a mystery as to how this girl obtained such a privilege, but Amanda realised that it had fallen into her hands for a reason. Without the obstruction of fares, the whole of Britain opened up for her like some elaborate flower, ready to ooze its precious nectar. She googled train routes across the rest of England, Wales and even, with some timidity, Scotland. The red patterns spiralled outwards, running their veins lusciously across the green countryside, alongside rivers, canals, forests and coastline. She looked up towns and cities, high speed connections and leisurely scenic routes. There was so much to see that soon enough, Amanda could hardly contain her excitement.

She would take time off work to live on Britain’s trains. How difficult could it be? She would give herself up to the whims of timetables and route planners, to vague and uncertain destinations and journeys. There were some trains that ran through the night. There were stations with shelters that didn’t kick you out. If worst came to worst, she would tap into her savings and stay in hostels and cheap B&Bs. The whole while she would assume her new identity. She would be Marianne Holbrook. She would never be lonely.

She phoned up her work the following morning.

“Hello Gina,” she said, “can you tell Mr. Raymond that I’ll be gone for a few weeks?” Gina, the manager’s personal assistant, raised her voice to a shrill pitch.

“What do you mean, gone a few weeks?”

“Oh, I’m going away for awhile. My circumstances have…changed.”

“‘Manda—” She cleared her throat loudly. “I’m going to need a better explanation to give him…do you have a doctor’s note? Are you leaving? You’ll have to hand in your notice, there’s procedure—”

“Tell him I’ll just be gone awhile. He won’t mind. Have a nice day, Gina.” Amanda hung up. For once, she realised she did not care about procedure. She stuffed her phone back into the side pocket of her rucksack, and turned back to the window. It was partially open and a cool breeze rustled the bare skin of her neck, which felt deliciously naked without her long hair to cover it. April hadn’t brought many showers since it turned its first few leaves; in fact, the weather had been glorious. Outside the carriage window, the sky was a bright bright blue and the crumbling buildings that skirted the city gave way to fields which rolled over and over in verdant, romantic green. It took forty minutes before they were properly out of the city. Once the ticket inspector had checked her railcard, Amanda plugged in her headphones and listened to an old Cat Power album.

She had to change trains a few hours in. The whole process was far less stressful now that she had no fixed destination, no time constraints. Every hour was her own, and time itself did not matter. She sat on the cold station seats, trying to read a leaflet about a local whisky distillery that she had picked up by the ticket gates. People looked at her differently with her new hair. Girls glanced at her with lingering intrigue. Boys rarely noticed her, or else they had to do a double-take. Amanda wasn’t sure if these were good double-takes, or bad ones. She wasn’t even sure what the difference was.

As the station clock clicked to ten o’clock, Amanda checked her phone. Still no texts. And yet, why did she care? She had already told him it was over.

She travelled up and down the whole of the UK. She spent a day in sunny Brighton, looking out to the limit points of this country she called home, at the sparkling lights at the end of the ocean. In the nightclub that evening, she found herself dancing to Eurotech, face gleaming with metallic makeup and sweat. A stranger slid his hand to the back of her neck and she let him kiss her amidst the flashing lights and thumping music. His mouth tasted chemical sweet. Outside, gasping for breath on the beach pebbles, she wondered whether this was something Marianne would do. Take things on impulse. Treat people like shadows, passing through your day, swelling, shrinking, disappearing. Somewhere in the darkness, the sea whispered its history of secrets. The city withheld its judgment.

Back up the country she travelled. She skirted round London, past the rolling hills of the South Downs; past Basingstoke, Luton, Milton Keynes. The changing accents haunted her with their shrill cacophony. She slept in a Travel Inn that night, washing her hair with the complimentary lemon shampoo that smelled good enough to eat. It was a very lonely motel: all the corridors were empty. Even the cleaners drifted along like ghosts, never looking up or smiling. She caught herself checking work emails on the WiFi and had to force herself to stop. She took a small vodka from the minibar.

What would Ruaridh say to all this?

Night after night, the meaningless names drifted through her mind. She had seen so many towns and cities now that she had lost her sense of what made each one distinct. England became unreal, this vast, impenetrable stretch of motorways, train tracks, telephone wires and suburbs. The crowds and the people and the buildings were different, but each time she felt the same. She did not feel real, floating aimlessly down street after street with no direction or purpose, nestling into the armchair of yet another Starbucks. Amanda told herself she was just exploring.

Sometimes she found herself wondering what Marianne had studied at uni, what she now did for a living. She imagined her, all cropped hair and smoky eyes, leaning over a desk at some sleek fashion magazine office. She pictured her in a court of law, sharp in a suit, scrawling notes. She saw her lifting weights at a gym after a hard day at the bank. She saw her serving tables at a classy restaurant, drinking martinis at some downtown bar. These were all possibilities. Marianne was made of possibilities.

On the train from Birmingham, disillusioned with cities and their grey array of indifferent buildings, Amanda managed to bump her way onto the first class carriage. This was something Marianne would do, sleek and easy like her hair. It was simple enough to turn tricks when you were less self-conscious. She brushed her fingers over the plush seats and nestled into her headrest. A skinny man dressed as a waiter came round with a trolley bar and every time he passed, Amanda ordered another Bloody Mary. She licked her lips as he stirred in the celery, the other passengers impatiently waiting.

Three drinks in and she kept dialling his number on her phone.

“Come on Ruaridh, pick up,” she hissed. People around her were staring. She was an odd sight on their carriage, with her little white belly poking out of her cut-out dress. She dialled again and again and of course he did not pick up. It was three months since they had last spoken, since she told him they could no longer be together; three months since the silence started, since she cut herself off from the world. And yet, a fortnight was all it took. Two weeks since her first outing as Marianne Holbrook.

“You never tell me what you want, how I can make things better for you.” Is that what he said to her, or did she say it to him? It hurt that now she could hardly remember; there was a time when she thought she had the words they exchanged engraved in her soul. Now it seemed, they slipped away, easy as the faces left melting on the platform as the train pulled out of the station…

She was in Leicester, Nottingham, Coventry. She found herself addicted to all the stations, their absolute sense of space devoid of place. In the stations, everyone could be anyone. She liked the dull parquet floors and the green painted railings and the matching uniforms, the logos and slogans, the slow and constant stream of announcements. People coming and going, bags and suitcases rolling along, teenagers moping around by the Burger Kings, waiting to be asked to move on. In so many ways, each station was the same. Aside from the stacks of leaflets advertising local attractions, it was easy to forget where you were. Each one was a kind of anywhere. Accents blended and clashed and Amanda felt like she was in some way everywhere in Britain at once: the stations were just another node in the network of cities, people and identities. The same chain stores brightened her view as she stepped off the train. She started buying the exact same things every time: the superfood salad from M&S, the Wrigley’s gum and magazines from WHSmith, the treat bag from Millie’s Cookies, the almond butter hand cream from The Body Shop that depleted so fast, what with the air conditioner on the trains drying out Amanda’s skin. It was so satisfying to follow a pattern.

“What’s your name?”

It was the day that somebody broke the pattern. She was hovering by the ticket gates at Preston station, clutching her railcard and hoping to catch the northbound train.

“Am-Marianne,” she found herself saying in reply. The stranger was an old man, laden with a heavy-looking rucksack.

“Ammarianne, it sounds Greek or something.” Amanda bit her lip.

“I’m Jim,” the man added. He wore an old tweed cap and had a vaguely Scottish accent. She did not know what to say, what he wanted from her. She thought about what Marianne would do, the possibilities that the interchange offered for experimenting.

“It’s actually Marianne,” she said.

“Hm?” he was checking the screens, squinting to see his train time.

“My name. Not Ammarianne.” She forced a smile.

“Where are you heading then?” He gestured towards the board of departures and arrivals.

“Well, somewhere up north I think,” she replied vaguely.

“Glad to hear it,” he said, “me too. I’m a fish out of water here. Scotland is a good place to go for the lonely.”

“Yes.” She hadn’t planned on heading that far north. Carlisle had been her limit point.

“Oh. Well,” he hauled his bag from the ground. “That’s my train. Better hurry.”

“Bye,” Amanda whispered, watching him stumble through the ticket gates. Just before disappearing around the corner of the platform, he turned and shouted out to her.

“So long, Marianne.” She could see that he was grinning and she did not understand the joke. What would come upon a person to make them approach a stranger like that, for no reason other than to say hello? It was so foreign to her, that kind of politeness, that pointless brand of interaction. Stepping on her own train, the thought of the man lingered in her mind. So easily he had broken the silent contract of anonymity which seemed to govern the stations. Was this something she could do too?

The thought of talking to strangers made Amanda feel powerful. She knew, then, that Marianne was the kind of girl who had no problem letting her guard down.

They had thrown her off the train where she sat in first class. She had drunk one too many Bloody Marys and was slurring nonsense at her fellow passengers, bits of celery still stuck in her teeth, tomato juice stinging her lips. It was difficult for her to recall now, but she had more than once broken the silent contract herself. She had not so subtlety propositioned a businessman, declared to everyone an undying love for her ex-boyfriend, blithely told a woman that she should eat less of those chocolate bars because they were making her fat.

“But don’t worry,” she had droned on, “look at the state of me too,” she pinched a roll of flesh that clung to the skin of her dress, “I’m gonna lay off the cookies too once I get off this ride, once all this stops…” She had promptly vomited all over the polished floor and the conductor had to clear it up while the train was still moving and his mop bucket sloshed and then at the next station he escorted her to the exit, while everyone eyed her with disdain. She threw up again on the platform and knew that night she could not stay at the station. The world had clocked her for who she truly was.

The thing was to keep moving. She got herself to Blackpool on the bus and won some money on the slots. There was such a pure satisfaction in the click and spin of the fruit symbols, turning and turning. The leap in her chest when they matched up: three bright sets of cherries. That night she watched the boats twinkle over the bay, the carnival music blaring wickedly from the Pleasure Beach. There were couples everywhere, locking lips as the blue lights shone down from the rides, as the waves slushed gently on the sand, as the breeze whistled in the cold dark air. Leaning over the pier, Amanda ate fish and chips drowned in vinegar, hoping to cure her hangover. Her phone bleeped with a message from her mother: Hope you’re OK honey. Guess who I bumped into in town today? xxxx

Amanda hardly wanted to know. It was probably an old school teacher, or some pal that Amanda hung out with in primary school.

Who? x The grease from the fish supper made thumb prints on her phone.

Ruaridh, of all people! and we thought he had gone away!

Ruaridh?

I don’t know how long he’ll be here for. He was asking after you.

Not that he ever texted her back. Not that he ever really tried to touch base anymore. She flicked through her messages to him:

I’m sorry. Can we talk?

Please can you answer the phone. I want to explain.

I miss you. I’m faraway from home and I still miss you.

Call me back.

Please Ruaridh, call me back.

It had been so long since they had talked that he had started to appear to her only in the abstract, the name on her phone a source code that might unlock some pattern from the shards of memory resting useless in her brain.

And yet he had asked after her; he had spoken to her mother. Had he perhaps changed his number? Was his old phone lying, battery dead, at the bottom of the desk drawer where he kept his protein shakes, his condoms and badges and passport?

She thought of those texts, drifting on through the ether, directionless as she was. Town names and station signs blurred into one. Even the old-fashioned stations seemed the same, with their pretty red brickwork, their giant clocks and gleaming phone boxes. The whole journey she had been going nowhere, but all the while she longed for one destination. Was it him? Could it possibly just be him? The city she had lived in all these years seemed so distant. It felt impossible, the prospect of just going home. In the carriage with the tables, the ragged newspapers, the empty bottles and coffee cups, she was leaving her old life behind.

The train was so quiet. A little girl was licking crisp crumbs from her fingers, staring at Amanda across the table, eyes wide and oddly fearful.

What does she want, what does she want?

She was in Scotland now at last, passing by sparkling lochs and pine-covered mountains. She hadn’t planned on coming here. The train just kept going, rolling on slower and slower, and Amanda had lacked the energy to change her route at Carlisle. Scotland seemed like the end of the universe. It was easier to stay on the same train, easier to let the world direct her like this. This was the land of accents she could hardly understand. Silvery land of wilderness and silence. Everything enveloped in mist. Everything cold, mysterious, romantic. The train tracks wound dramatically round mountains, farmland, fields pregnant with the summer harvest. Sometimes the mist cleared and Amanda would glimpse patches of bright sky. In the past few weeks, the evenings had grown longer, so that now at half past eight the carriage was bathed in a soft yellow light. The grass that Amanda could see from the windows was a kind of supernatural green, so vivid it was difficult to look away. The fields stretched out into endless hills, lush with ferns and trees, fluffy white sheep and even the odd telephone line. Often they passed little cottages and farms, or villages speckled with lights that twinkled through chimney smoke. There were very few houses in the mountains; the train was disappearing into somewhere very remote. Surely by now they should be in Glasgow, or maybe Edinburgh? She couldn’t remember which one came first. All that surrounded her now were the mountains, snow-capped, rust-coloured, rocky, sometimes a deep and sinister green.

It struck Amanda that the mountains reminded her of her father, who used to take her up to the Lakes sometimes when she was young, forcing her to learn the maps even though the sight of all those squiggly lines and symbols made her dizzy, more disorientated than she was before. He made her traipse across acres of countryside, reciting his favourite segments from the guidebook, stretching out the hours with his constant narration. Reviving himself with cider at some farmer’s pub, where the locals would stare at them suspiciously as Amanda sipped her lemonade and the whole while her father never noticed. It was in the summertime, two years ago now, that he died.

Nobody talked about it. Amanda’s parents were halfway through a messy divorce when he discovered he had cancer. It had all happened so fast. The appointments, the vomiting, the weight loss – the transition into anonymity and sickness.

At rockbottom. Please call me, even just for a minute.

She hated herself even as she typed the message. All I want is to hear your voice. The thought of all those pathetic unanswered texts piling up on his phone made her physically sick. The train churned on, its sluggish rhythm another source of her nausea. The only messages she’d been receiving were voicemails from work, telling her she’d missed deadlines, meetings; telling her they were disappointed, telling her not to bother coming back.

In the cracked glass mirror of the carriage toilet, her reflection looked strange somehow. There were new shadows etched under her eyes, greenish as some disease. Little flecks of red that veined the whiteness round her irises. She realised she hadn’t slept more than three hours a night for weeks.

She thought of her father, emaciated, pushing a supermarket trolley, his fingers gripping the bar so hard you could see the tendons round his knuckles. The smile he forced as she shoved bottles in the trolley was grotesque and strange: a Cheshire cat grin smeared upon those hollow cheeks. He was buying her vodka because she was going to a birthday party, because she was not yet eighteen – a clandestine mission concealed from her mother. She thought how he would appear then to a stranger, vodka rattling in the trolley, this gaunt figure swathed in scarf and overcoat, incongruous against the mildness of that May.

There were secrets in these hills, Amanda thought, that nobody knew. Such endless stretches of greenery, pure as the wool on a lamb’s back; stretches which no man had touched with his brick or chisel. In the hills, there was a sense of possibility; in the hills, you could be free.

This freedom was quite terrifying.

The train had slowed as it finally approached a new destination. Nervously, Amanda fingered the plastic coating of the railcard with Marianne’s face on it. She was tired of always playing a role. It drained you, the whole process of never revealing your true name, spinning webs of lies to perfect your anonymity. Brushing past strangers and missing out on meaningful conversation. Out of a picture she had fashioned an entire existence, but now this identity felt crude and shallow. She was tired of staring out of windows, tired of flirting with strangers. She found herself missing her mother, the 24-hour shop down the road, the memories that haunted her home in Bristol.

She disembarked from the train in some small town, the name of which she couldn’t even pronounce. Everything was tiny, shrunken somehow, like a toy sized version of reality. Standing outside the town’s single newsagent, Amanda checked her phone. There was no signal whatsoever. She walked round and round the village, but to no avail. She knew then that she had completely left civilisation behind.

This was probably the loneliest place she had ever visited. Her father had never taken her somewhere like this: his favourite destinations in the Lakes were the comparatively bustling towns of Ambleside and Windermere. Tourist hotspots with ferries and buses and trains. Here, all the pretty streets, with their flower baskets, their plant pots and cobbles, were empty. Only the humming bees provided company. It was, perhaps, a town that time had forgotten.

Amanda realised she was starving, that the pains in her stomach meant something. She came across a tiny shop which seemed to be the only amenity in the village. The sign in the window said: “No More Than Two Children At Any One Time”. She stepped inside and a bell tinkled. The woman behind the counter greeted her in a thick accent. It was not like the Scottish voices on the radio or telly. The shop was so small that Amanda had to duck her head the whole time as she looked around. There were only a handful of aisles, shelves half stocked with off-looking bread and chocolate bars and tin after tin after tin of beans. At the counter there were a few fresh rolls and some fruit. Amanda bought what she could and thanked the woman.

“What brings you to these parts?” she asked, noticing Amanda’s conspicuous Englishness, the Queen’s face on the £5 note she handed over.

“I don’t know,” Amanda admitted. “I guess I’m looking for something.”

“Well, you might find it here. Folk have found worse in this village.” She smiled wryly and the wrinkles of her face creased up like the sand folding in patterns left by the tide.

“Oh?” The woman handed Amanda her change but her lips remained shut tight. Outside the shop, the weather had changed ever so slightly. There was a faint breeze stirring in the surrounding trees. The village seemed to be in a valley, protected from the harsher elements. It was a miracle there was a train station at all here – probably it was some relic from the Victorian era. Maybe there was a coal mine here once, or maybe the roads were in such bad condition that even the buses couldn’t get out this far into the wilderness. Amanda had the vague sense that she was in the Highlands, but she couldn’t be sure. The air had a thick moisture to it, a soothing texture to every breath she took, to the smoke that rose from cottage chimneys, the clouds that curled round the snowy tops of mountains.

She wasn’t quite ready to eat yet, though she was very hungry. She wanted to explore every inch of the village first. There were a handful of tiny winding streets, windows in miniature, house after house with Gaelic names etched on the door. Wild cherry trees flowered with late blossom round a square, in the centre of which was a war monument. Amanda stood and read all the names of the deceased carefully. Everyone seemed to have the same names: John and William and James. She touched the thick grey stone and its coldness seemed to spread through her bones. All those people, whose minds and bodies were lost in the turmoil of something far larger than themselves. The memorial seemed the only thing, apart from the ancient railway line, that connected this place to the outside world.

Ruaridh was a soldier. His job was to fight in whatever war they sent him to, to follow commands with cold precision, to give himself up to the mechanisms of higher forces. He had been in Iraq when Amanda was still at school and Afghanistan when she took night classes in college, serving coffees in Starbucks during the day. This whole other life had washed over him, while she remained at home, slowly growing, mostly staying the same. He had seen things he could never explain to her.

I miss you. I’m far away from home and I still miss you.

Perhaps his reticence was worse than hers. Perhaps he was the one who was truly unreachable, the one who could never match her in their silent exchanges beneath the sheets. She remembered the way he used to shake with nightmares, though denying them upon waking. It could’ve been his name, up there on a monument like this. Only no, because soldiers these days didn’t fight for glory, not like the old ways of valour and poetry and bravery. These days, even more they did not know what cause they were fighting for. They were just sent away, hardened with protein bars, coldly dished therapy and standardised training. She thought of the muscles in his neck, quivering as he spoke. Despite the strength of his body, it seemed all the time like it might snap, like the stem of a rose.

A photograph from the news: skinny, doe-eyed children, the reverberating dust of explosions, debris flying through a colourless sky. Soldiers in their khaki uniforms, praying for this world that they had not yet had time to properly love. For this world they might lose.

She remembered kissing him for the first time, in his mother’s living room, while they watched a black and white movie. The sound turned down, the whisper of their voices rustling the air. The walls would still contain those voices. Her fingers brushed the cold marble setting of the monument. Youth and innocence. Was that all that love was worth? And what about war?

Was loneliness the reward for all she had taken the guts to sever?

She thought of the scarring on his arms, the swellings of all those magenta welts which flowered outwards in jagged patterns, not unlike the etched textures of tree bark, both coarse and strangely smooth. The burns he had suffered were some price he had paid, his dues to the people he lived and fought for. Sometimes he would lie awake at night in pain while Amanda rubbed them with expensive oils and honey. She would watch his eyes close before the tears could leave them.

She turned away and the wind picked up and stirred the trees, shaking fistfuls of cherry blossoms from the branches, swirling them in the path with the shrivelled daffodils and the silver gravel. Some of the blossoms settled in Amanda’s hair. She walked away, past the church, following the tinkling sound of a river. She sat on its mossy bank and ate her apple, watching the midges rise above the water, spiralling in the gold light playing in the reflections of the pines in the river. Afterwards, her mouth felt sour as her soul. She wished she had cigarettes. She looked through her texts.

At rockbottom.

At rockbottom.

At rockbottom.

Three times she had sent it. Three times, and no reply.

She pictured herself, tied to the stir of the riverbed, pulled along by an unseen current. She would let it drag her where it willed, battering her on the sharp stones.

Somethings you just have to let go. Her father, whose ashes they scattered from Friar’s Crag, looking out upon a brilliant body of water, the light in the sky the colour of indigo as she watched her mother tearfully smile her final goodbye. The wind in the pines, the light on the lake.

Somewhere, Ruaridh would have stood among dust and chaos, a gun in his belt and his heart encased in a golden cage. In sparse Internet cafes, he would have written all those emails to her, sent her pictures of the crumbled houses and the desert. From this lush valley of greenery and quiet, it seemed another planet. She realised, then, that she was so many people. She wasn’t just the Amanda that maybe he had loved and grieved over and then ignored. She was the girl who would always mourn her father, who would long for summer afternoons in the Lakes; for the taste of ice lollies, for the breeze on her face. She was the lonely employee, biding her hours in her stuffy office. She was all these Amandas. But she was also Marianne: this monster who had burgeoned from a picture, larger than life, a figure of surface and depth, past her expiry date, readymade to inhabit. She had built this person from nothing but a picture, its plastic gloss the surface foundations. She knew, then, that she had the power to put herself back together.

I want to explain.

The midges danced on the water. The clouds moved overhead, the gloaming settled its purple shadows around the pines.

She no longer needed him to remember. Probably he was broken too, broken beyond her control. He would be back for awhile, but the call to leave would always drag him along again. War was, in a way, another kind of travelling. She did not crave the same excitement, the same desperate thrills of horror and danger that lay in the army; but still it was the impulse for movement that drove them both. She saw that now. They were both trying to escape the same lonely feeling, the hollowness that gnawed out from the bones that once held them up, that once fused their connection to the land and earth. To each other.

She caught the last train out of the village, finishing the last of her picnic. She watched the river’s silent starlit glitter stretch along the valleys, turning round the hillsides. She waited for her phone to regain its signal. She knew when it did, she would text her mother back at last: Tell him I’m fine.

And then she would delete his number from her phone.

And later, when she fell into sleep, she finally realised what the old man at Preston station had meant when he bade her goodbye. What it was he was quoting. The rich deep baritone of Leonard Cohen drifted into her mind and she remembered, she remembered. A song her father used to play on Sunday afternoons, smoking illicit cigarettes from the bedroom window while her mother was out getting the shopping.

I’m standing on a ledge and your fine spider web

is fastening my ankle to a stone.

And the chorus came to her, easily as sleep did, easy as the loneliness that now she embraced, languid and happy; as easy as the slow tug of the train that would take her who knows where, that would link this life and this self to the next one and bring her always some fresh memory that was better than home:

Now so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began…