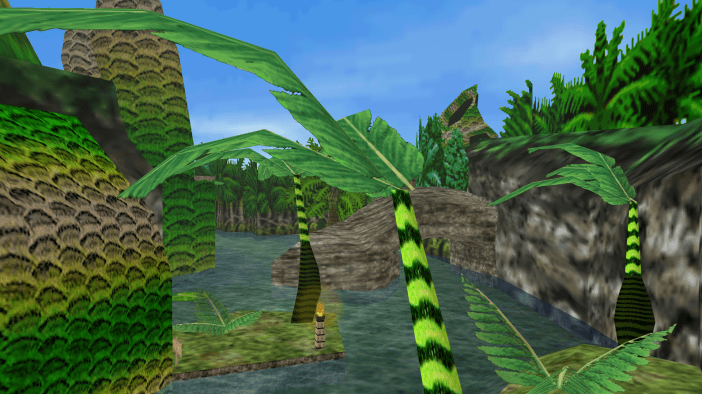

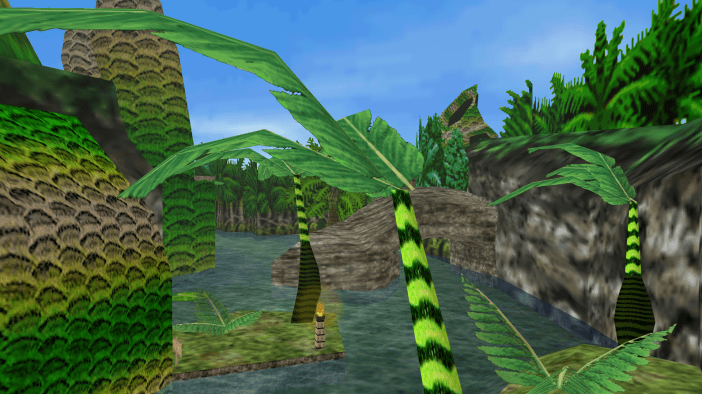

This time last year I wrote a pretty weird story when I was bored and tired & wired and it was probably 4am. It’s called ‘The Swamp’ and I decided to upload it cos it fits pretty nicely with some ~ Gilded Dirt ~ themes. You can read it HERE.

This time last year I wrote a pretty weird story when I was bored and tired & wired and it was probably 4am. It’s called ‘The Swamp’ and I decided to upload it cos it fits pretty nicely with some ~ Gilded Dirt ~ themes. You can read it HERE.

A Voicemail for Some Scots Poet

(scrawled in bed on the morning of Burns Night)

Your thatched roof I hid under with a jar

of rhubarb & custards, birthday gift for a friend

of the old-fashioned sort. Hiding my anxiety

with the pishing rain and roses for eyes,

I tried not to cry with the waiting.

Alloway was never the place for me,

though tourists once snapped my photo

sitting at the bus stop in my pinafore; maybe because

the bus never came as before and I seemed to them

an exhibit of the idle, plaited poet, crouched

and concrete with schoolbag and notebook.

I tried then to draw out my longing

but the salt water was sore and washed

each sketch away. At fourteen I took blackouts in the park

with the help of old Glens and Bell’s whisky.

Now they keep putting pictures of your face

under the hair of Che Guevara but my wi-fi

is shite as I look farther for the secrets

of some revolutionary conspiracy

known only to Twitter.

You were the smell of burnt haggis

in primary school kitchens, the passion

of incompetent, childish longing;

every January blackened for lack of snow

or a coffee topped with Irish cream

and dreams of home.

I’m trying to make you more of a meme

but the birds sing merrily of some Scots

that got tangled in my mouth, made a scandal

of the girls slinging glittery hooks

against the Ayrshire weather, dreich and pitiful

in the stench of manure and nicotine.

You made poetry from head-lice and folktales

while I’m starting out on madness and palm trees

and the single best beat to snatch, ecstatic

from a still calm sea. Dylan loved you

and god knows I share your fetish for roses,

though mine are long-glitched out of semantics

or flourishing poesy. The inevitable middle name;

the rose is a dead rose, a broken cable.

Every time they sing Auld Lang Syne

the spell snaps tight like the cutting of tartan

on a slut’s dress as she readies herself legendarily

for bewitching auld Ayr’s errant men. I love her

with the crimson candled extravagance

of the urban occultist, dull and lonely. She’s got legs

enough to kick them in the Doon when she’s finished,

chortling like a slot machine.

A match, perhaps, for the farmers of the toon

who tossed my friend in a hedge when he tried to join them at school

in talk of fags and cattle and the internet equivalent

of cutty sarks. It’s a fell swoon for the rest of us,

with ardent cries for freedom

from the trendy alt-truths of southern politicians

and the armies of bagpipes swarming the park

to practice for every month of fucking summer.

That hot breath steaming the January air,

some promise for Scots blood running cold in the veins

of my milky Englishness. I’d swap it all

to be back there, sugar-tongued and sweeter

in teenage confusion, rain spilling off

the thatched roof, every drop fused

with a purer kind of truth like the shape of your words (Romantic).

Can you call me dear Rabbie,

if you’re able? I’m waiting, but the rose

is a dead rose, a broken cable.

[ a daily free write ]

The weather turns, ineluctable as that mist that mysteriously fogs up my glasses (Footnote: Why do I wear glasses? Something a man once said about parallax and the need for clarity of distance, the reassurance of one’s own substance). The city is a haze of something else today, foreign as a postcard marred with scratches of time and travel. Must I always be up to my neck in vapour, in unfinished melodies? They always catch: grooves on a record, gum on the pavement, hair snagged in a glue binding, specific as a bookmark; melody after melody. The notation would be very messy. I’m picturing spaghetti-tangles of quavers, misplaced on the staves with no home of their own. What of this note? oOoOooooooooOOOooOooaaAAAaaaaaAaoo……. Does it belong in the sonic realm of an F#? The problem is, I picture my life in A minor, every time. The soaring long echo of a siren call; so sad, so sad. Picture this, pretty fake glass vase, all containers of vapour, elaborated with black-printed Celtic patterns, impenetrable as ersatz ~internet~ Japanese.

One attempt at pottery is quite the attained luxury. I think I will try out something new. The raising of a blue hand in order to trace the pulse of purple veins. Not too bad for a hologram. This is sweet and clear and maybe okay. Like walking past the graveyard of pines. Must I call it that? Too long it has been since I’ve trailed through a cemetery. A habit picked up from my grandmother, I glance at the old headstones, my brain knotting in each line and crack and crumble. I forget dates; they fall away. When you realise that you are walking a few feet above the bodies of dead people, your heart does a turn and slips to your stomach. The ground is so soft and mossy. Flesh is a good fertiliser, it spreads lush bright vitamins to the soil. In fact, it might be quite nice to lie down in and dream.

If I slept in a graveyard, would I have reveries that channel the dead? It’s a distinct possibility, the amount of fragmentary matter that must float in the air like electricity. The hormone we release when we die: dimethyltryptamine, DMT. They say it makes us see fairies, elves and tunnels of light. Lost soulmates dwindling in the twining of shining limbs. Silver rings in a stranger’s nose. Near death, the liminal weirdness of the world crosses its own boundary. No wonder I have always loved the word psychotropic, its connotations of a spliced brain opening out like a Polly Pocket to uncover an island of swaying purple palms, a guava pink sea, an assortment of oozing neon beads. This great, gritty, sparkling geode. Would a brain like that bleed? Do brains in general even bleed? The lavish quality of this vision is undoubtedly a product of sugar cravings. The dangerous dip, the faint-headedness. Our bodies being an assortment of chemicals, it’s only natural that the synapses of our minds produce very queer imaginings indeed.

Pineal gland: essence of palm. The oil extract no longer lucrative in worldwide trade, though popular, cheap and downright nasty. Spread it on bread like honey and sweeten. It makes things swell, tighten.

Things to desire: serotonin, colour, daylight. There was a time where I substituted existence for an array of colours, the kind that come straight out the packet. The need for something pure and vivid, so vivid as to seem utterly distilled of all trace matter, was completely upon me. Splat after splat after splat. I could have squirted that colour on my tongue and hoped for the same result of a manic acid trip. I wanted to see the gravestones melt, the names shimmer and vaguely disappear, leaving scraps and lingerings of unfinished letters. Is it possible, really, that some expert kneeled in the moss and carved those names so beautifully?

Crack open the sky over the sea and tell me what you see. The bold aroma of a rainbow comes quickly and glows like some other sun is ripening behind it. A pale blue sun, perhaps, stolen from Mercury. Planets out there, swapping their radiations of time. Down below, the ocean groans under globules of oil, fat black spills which ooze and spread. Each secretion has its location hidden; sometimes gushing, sometimes slowly swirling. I think of butter melting into chocolate, ink being marbled in gelatinous jam. The favourite taste, all bonfires of strawberry. Some god is spinning the water with a cocktail stick, languid and bored like a hungry person in a bar, waiting for love. We hallucinate, don’t you see? There is a complete quality to what comes next, the fiery upturning of all this trace matter. Waste. Be flamboyant as an artwork. You pinch the thin skin of each of my fingers and the lightning shoots right through me.

Things to desire: rock pools of igneous glass, starfish, the dying white rose at the side of a grave.

I hear the knell from far away. Such tocsins call me back from the realm of the dead, though I am happy here, my body breaking down into succulent little pieces. The woman opposite me mutters litanies to herself; stickily, as if each word were cheaply enthroned in lipstick. Is there work still to be done? These days, I mix the colours. I like to see the vibrancy break down, meld into subtler hues, details you see only up close. The paint sticks in my brushes, the glitter of light in my lashes. It’s not mystifying anymore. The greyish haze is my outpourings of smoke, enough to cover the whole skyline, swallowing up what good is left of tomorrow. I inhale matter in wholes and halves. Like yesterday, it will be black (the city, that is): gilded, ink-ridden, brilliantly viscous. A whole ocean will roll from the distance and its golden ore will cover us, just so many bubbles of oil pasting our brains. For now, it rains.

***

It’s not all about realising you can get 10% off at Topshop again (although my ID photo is so bad this year I’m no sure I can brandish it in public). I didn’t know what to expect, going back to uni after a year out. It all happened so fast. Working for over a year as a full time waitress, doing 35-55 hour weeks, I didn’t really give myself the headspace to prepare myself for what uni entails. Despite knowing for several months that I had secured my place, a Masters in MLitt Modernities at Glasgow Uni just seemed something far in the distance, the uncertain plane which I would embark upon after an endless summer.

No matter how it feels at the time, summer is never endless. August was a strange old month, and horrible, tragic things kept happening around me. Amidst all that, it didn’t seem real, making my way through the infernal labyrinth of MyCampus; applying for scholarships, spending inordinate time staring at screens again, making lists of things to be done. I found myself in a room up high in the Boyd Orr building, listening to the inimitable and infectiously enthusiastic Rob Maslen give a speech about the strange history of these hallowed walls; being introduced to the university as if it were the first time all over again.

It is weird going back to the same university after a year out, especially if you’ve not gone far. I walked up the hill listening to Tigermilk feeling blissfully like a total Glasgow cliché and it was like nothing had changed at all; it was my first seminar of the semester and I felt bright and hopeful. Glasgow gifted us with a particularly gorgeous autumn, trees bronzing languidly into darkening violet as twilight fell and I was still sitting by the fountain, making notes on poetry. I tried to take walks in Kelvingrove as often as possible. Quite quickly, however, the daylight ran out. Nights drew in. Still stuck in waitressing mode, such thing as a sleeping pattern proving an elusive remnant lost somewhere back in 2015, I found myself going to sleep at 5am every night, often staying in the library till everyone on the floor had left and the lights kept going out automatically. There I was, alone in the dark in front of a dull-glowing screen (though one must note the upgrade in PCs at Glasgow Uni Library, which are much preferable). It’s easy to spiral into that maddening routine, trying to do all the reading, make notes on everything. I’ve never been a meticulous note-taker, not by a long shot, but I like to handwrite things and have a tangible record of ideas and theorists and possible avenues for further study.

I would walk home at 2am, stumbling tired-eyed through Kelvinside, hoping for a glimpse of the river, some tangible reminder of nature. How long had it been since I’d seen the sea? During reading week, I allowed myself a cheeky day trip to Arran, which felt so unreal it was almost magic. The days passed and ideas started to percolate in my head. The power of procrastination unleashed itself again. I did more creative writing in the past three months than probably I’ve done all year. I guess the more you read, the more you want to write. I sat on level 11 and watched the sunset over Park Circus, making airy, vague notes about queer temporality and thing theory on a 60p sketchpad. I went to seminars and was reminded of how nice it is to listen to people share a subject, to listen to experts talk with passion about something they must have covered a thousand times before and yet still they can find fresh things to say about it. To actually talk to said experts about such interesting topics (instead of merely serving them glasses of wine and plates of fish, as the Oran Mor waitress will often do for GU academics). Although a bit scary at first (not least because I had a screenwriter and published author in one of my seminars!), it was nice to actually have proper formal discussions about books again. Often we veered slightly off-topic, with Trump becoming the proverbial wall against which we hit our heads in frustration, but everything felt prescient, useful. I went to visiting speaker seminars with the likes of Stephen Ross, Graeme Macdonald and Darren Anderson, who talked about all manner of interesting topics: Beckett’s invention of the teenager, petroculture and the politics of space and architecture. Having been at Glasgow Uni four and a half years now, I was still struggling to find half the rooms and buildings I needed to get to.

I went to a couple of nights at The Poetry Club in Finnieston and actually read poems aloud to real humans. Got a few wee things published here and there. Went to a ceilidh. Realised that I want to do lots and lots of creative writing and really try and learn from people. Started writing music reviews for RaveChild which has been really rewarding, not least because it’s encouraged me to broaden my musical horizons and go to more gigs. Started tweeting again. I managed to go to a few Creative Writing Society workshops, wrote a collaborative sonnet and played around with tarot cards. Went to Creative Conversations at the Chapel and saw very smart and fascinating people talk about writing: Amy Liptrot, Liz Lochhead, Mallachy Tallack, for example. Developed many creative crushes on various academics.

My stress levels tend to rise in tandem with the library’s rising busyness and so I stopped going altogether about a month ago. I’ve more or less forgotten what sunlight is, except for the wee slant that comes through the window of the building in Professors’ Square where every Thursday we had our Modern Everyday seminar. I sit in bed everyday and try and write and write. I spent the first four weeks of this semester trying to read a section from The Derrida Wordbook everyday, until my brain started to melt a bit too much and I was thinking in riddles. One day I was so tired I woke up at 10.46 for an 11am seminar but somehow still made it on time, looking like something the cat had dragged in. I tried to get my head round Blanchot, and even went to a reading group where we poured over The Space of Literature and maybe I came out with some sense of the link between writing and death. I wrote reflective journals for my core course seminars and every time came back to Tom McCarty references. The man and his ideas are just so seductive.

Coming to the end of my first semester as a postgrad student, I’m not sure how I feel. I didn’t wash my hair for nearly four weeks. On the one hand, my brain feels heavier, I’m exhausted, probably much less fit; I’ve lost contact with a few friends. On the other, I’ve got ideas all the time, I’m meeting new people, I can understand a little bit of Heidegger. I’m extremely lucky to be able to study at all, especially on such a well-run, exciting course like Modernities.

Things I miss about waitressing:

Going part-time, I still get some of these fun things, and less of the bad things. Maybe that’s a nice balance. The Christmas period is always a test for our sanity and endurance. Still, hopefully the feeling of handing in my essays will get me through the rest of the season, and if not god knows I have enough books to read to escape into! Maybe I should tidy my room first.

We arrive at the bus station. It’s four in the morning and god knows why people are still here. Where I’m from, people are in their beds at this hour; the old folk know the truth of properly impenetrable slumber, even mothers draw brief glimpses of sleepy solace amidst the screams of their babies. Chimneys may shudder, walls may fall, but people will sleep. No, the folk where I’m from don’t haunt train stations, unless they’re homeless and know the secret places where you can hide from the rain. Benches scratched with ink and tip-ex, territorial markings. Nowhere to buy spray cans. Nothing interesting to hang around for. Here, I look around and all the same places flash in the ugly strip lights: a Starbucks, a sandwich bar, a Marks & Spencers. Nothing open, except some stand selling donuts, which smell fucking lovely even though I hate donuts. It’s that hot promise of oozy sugar, mouth-melting jam and fluffy fatty dough. Chewy. I can taste it, just as the guitars kick in, clean as the stars which god knows in this city you can’t see.

It’s cold. It’s the beginning of August and I’m homesick like the kid stuck at space camp.

It’s dark as hell in my head, that little sleep on the plane still safe, hovering over my thoughts like a shroud. It’s not all that dark outside; traffic passes, the neon from bars still aglow. Signs reflect back in headlights. I blink, rub my eyes. I have this sense of something vast and black. I want to close my eyes, imagine this spreading, seeping oil spill, disseminating its viscosity out over every surface, every gloss or gleam of grease, the echoes of footsteps melting, the pavements dissolving to nothing. I dream of an oil that is precisely that: nothing. It is matter as nothing, it is fat and black and coats everything, inevitably, inexorably. The chorus builds. I can hear something pulsing, a faint chime that cuts through all the sirens; when you pay attention, the littlest things cut through. You just have to pay attention, I’m telling you.

No water, no sound. I’m following someone else’s footsteps. People are everywhere, bumping and jostling, bags clattering on the vinyl floor, the cold stone steps, the deplorable concrete. Wouldn’t the oil flood over all of this, covering even the star speckled whiteness of gum? There is a lull, there is a slow progression of chords. There is a sense that…no. The sleep will not come back. I fall into it; I’m on the bus now, it’s slow thumping rhythm echoing the song. People get on and off; it goes and stops. I don’t know this place, or that. The high-rises are imprints, no longer there. Innumerable blurrings of nameless shops, bars, boutiques. You wouldn’t recognise them. It is all glass, sharp-cut and brilliant. In it, I see the bus. I don’t see my face. I never see my face…

And yet there is a crushing. The smoothness compresses back upon itself, like someone scrunching an aluminium can. I dream of a Diet Coke, fresh from some fridge-freezer, the snap of its top, crack, clack; the way the fizz bubbles fast in your throat. Mmmm, aspartame. I am in a room that is someone else’s. So sweet, so lonely. When they are gone to the bathroom, I get up to look out the window, a foreign sheet wrapped round my shoulders. I see more of the glass buildings, endlessly reflecting. I cannot see the window, nor my face. I’m waiting to return. It’s like vertigo, all the glass and all the lights. I miss the darkness. Sometimes when I’m in a room like this, lying on the crooked bed with my head far away, I think I hear the meteor showers. They come back again, silvers and silvers of them, lilting and sprinkling like the softest, most intangible fireworks. I have this memory of November 5th, ten years ago maybe, spinning round and round on a roundabout in a park in the middle of nowhere, the sky shattering above me but even then I’m so indifferent, just whirling, singing something very random, the scattering mess of everything swirling in my head. And I could fly off to the soft dark ground and let the darkness fall over me and god I wouldn’t mind, wouldn’t mind one bit, just the last gasp of a drowned sailor and that promise of a ————————-

[a daily freewrite]

Sinister synths fill the bloodstream. It is very late, too late to be out walking like this down Kelvin Way which tonight is another planet, leaves falling slow like so many flakes of golden, sorrowful snow; not normal, not real, just swirling in loops and spirals, falling as if in slow motion—and my walking is the inversion, fast-paced as I cut through the piles of leaves, my legs making shapes against the air which is freezing.

I think: the spider at my window. It has lived here for months and is gradually fattening. Its web spreads daily like a tapestry; it lurches across its pretty stitches to devour some unsuspecting insect.

I think: it is too light to be dark. What is that spooky glow at the end of the road, why the blueish mist, the streetlamps the colour of mulberry?

In my ears like a virus the saxophone spreads, its screech rising to a terrible pitch; then falling, descending, counterpoint to that butter soft double bass…

The trees are too tall for a city. They are tall, sinewy trees – almost fully without leaves – which gather instead in great waves on the pavement swollen with the imminence of my kicking and scattering – they are so dry and crisp like just so much beautifully burnished scrap paper torn from centurial newspapers. I am very little, smaller than the fence posts, picking up the fattest five-pointed leaf, glossily gold and glazed with rain.

The familiar chords are placed in the air, like the liquorice laying of vinyl on a turntable. The air which would be so still if not for those billowing leaves, for the quiet display of traffic, which passes smoothly like a reassurance, like airwaves heard vaguely from beneath the sea of sleep. The sounds in my head sway as if I am rocking to sleep; I keep walking, walking…

Bars and cafes locking up for the evening, their emptiness betraying a certain extravagance of decor and objects. Why this painting? That mirror? What are you hiding? The screens of the evening are everywhere. One I may fall into, one I will crack and smash. I am pressed against the glass, watching the precisely symphonic arrangement of chairs and tables. I wonder which guest had moved the backs slightly, had pulled off the cloth, had spilt blackcurrant wine on the white linen like blood.

There is a screen in the distance, golden brown. An advert for Grouse whisky. The houses which look down on me are especially macabre, tenements of sandstone washed ashore from the bleakness of history. Ghosts are in the window, knowing the shadows of their past passing futures. I feel an affinity. These are curious ghosts. I am too warm. I shirk off my rucksack, my black leather jacket. I feel the air whip fast at my arms, bare. It is proper cold tonight, crisping and shrivelling the skin of my lips.

This sinuous, heavy, resonant bass. Is it in time to my quick footsteps? I feel myself slowing down, oozing in a scattering of atoms. I have lost my train of thought. Something about an essay, the impossible engorgement of several million objects. Just so much of Blanchot, of Stein’s poetry. I rub my eyes, reddened I guess; the lamplight too bright on the white bits. Such shadows! I am followed by my own tall, anorexic twin. She is Slenderman sized, long-limbed as a willow.

I feel like dark chocolate, like coffee. I feel quite decidedly empty.

The passing of strangers speaking into phones. They are all web-caught, a sequence of whispers. I hear them as if through the static of radio. There are cats screaming in distant alleyways; I imagine them mouthy, a jawfull of mice, ecstatic and tortured. A blackness comes over me again. The muscles slacken.

This is the lounge jazz of hell. This is the seductive coloratura twinkle of a mystical piano, the refusal of a chord to resolve itself, the slow-climbing bass, the way the xylophone draws us closer to a beautiful death. It is a shimmering, blood red pool. It is fire; it is lava, like noirish Irn Bru. The scarlet curtains part to reveal us. I think of the cave, of the spider, of the sapphire light. A bluegrass guitar severed, shredded in dissonance. The sweetest, purest soprano, worthy of Elizabeth Fraser, fair queen of Grangemouth…Here we are in the mountains, the laces of silver rivers, the dark pines, the water spilling over the ridges, the unfolding of clouds like a book of spells…Smell of woodsmoke clotting the tired red strands of my hair.

I am at a door. Is it the colour of midnight on a moonless night?

Still I am alone. The ghosts have departed, the album has finished. All is silence. I am home.

We decided to meet in a bar, one where old men gathered for their daily brew and crepuscular women exchanged knitted secrets in the shadowy corners, around time-gnarled tables. I knew you instantly: the Celtic heritage of your red hair, unkempt even now; the cream-coloured Aran sweater, too warm for this time of year—though you were thinner perhaps and therefore colder. Half-way across the bar I could smell your cigarette smoke. I could feel the way it was before, in your fingers, stale and yellowing, chemical; the ash splintered deep beneath your nails, the black clot in your lungs which throbbed as you coughed. I remembered it, the way you would sit up in bed in the middle of the night as if struck by lightning, the thrust of it right up your spinal cord. I would bring you glasses of water; I would stroke your arm as if my fingers were falling leaves.

A pint of Guinness sat in front of you, barely sipped. You were reading a book, wearing glasses. I had never seen you wearing glasses. What was the book? I try to recall it. Frank O’Hara, perhaps, a handful of scattered street poems; maybe something by Whitman. You always had a thing for the Americans. It was part of your mythology, the dream of the road, the need to leave the homelands. You hated this city, but still you were here. You had returned.

I pulled up a barstool and for a moment you didn’t even notice me; didn’t blink once from your reading. I grabbed the glass and swilled some Guinness down me, the froth of it coating my lips. It came back to me, old friend: that black, hoppy, toffeeish stout. There were all those nights: the sticky surfaces of bars, voices that rung cacophonies, inane words snatched from strangers. Outside, the brisk March wind that billowed my hair in your face as you smoked and smoked. I tried to deny the way I loved your smoke. I could’ve sucked it in all day, like you were giving me wisps of your soul. Sometimes, when I pass a smoker in the street, I have to cross the road—the tarriness smarts my eyes.

I suppose I was hyperaware of everyone around us. What would they think? Would it seem strange now, to see this thinness of a figure stealing their way to a table and taking a man’s drink? Would they notice at all? We were always conspicuous: it was the black lines drawn thick beneath your eyes, the fox-coloured shock of your hair; my silence, my obvious adoration. The swirling limbs and all the dancing, the clubs we were thrown out of for being violent. You wouldn’t see it now. If someone took a picture of us, we would be two strangers in a bar. They’d have to pick out the way I turned towards you, hoping for your notice. The drink would seem my own, anonymous. How could they know of our entwinement on any number of sofas, the graffiti of our names we sketched on the tables of trains, the countless coffees and cokes and sticks of gum shared as if mouth-to-mouth in our indivisibility?

I watched your eyes follow left to right along the page, so engrossed; as if looking for treasure beneath the lines, behind the lines, at the end of the line, the final line. Maybe you were waiting to finish a chapter. I longed for you to acknowledge me, to make my interruption.

How could they know, the way we would meet every day, in bars like this, and our spirits were the same? The spirits we drank and sank and raised? How could they know?

Just then, you folded the corner of your page. You reached over the table and clasped my hand, the one that still touched the Guinness. I saw your lips raise a smile, the eyes the same, sea-green aglow.

You said: “Hello.”

The glow of the oil lamp

melts through the misting dust

that coats the light in the kitchen,

all airy, greyish, mossy and ochre

as the painted walls

(…In the evenings and mornings there are the same

slants of sun or moon, geometries of the cosmic

playing games upon the carpet).

Two weeks ago, the gloom was cut

with a bunch of sunflowers, hacked clean with a knife;

their extravagant heads all smiles and brightness.

They lifted the mood when you entered the room,

skin acquiring that olivine hue

from the plants and the shadows;

reflection of the radio, whose channels

remain static, always, in lieu

of music, or a television crackling,

or a body that would clutch

you so tight in its sadness

as to suck away your own.

Crumbs from the dead hours

grow a fur of mould; the pages curl

on a stack of magazines,

whose gloss lacks immunity to dust,

which scuttles and settles

between the pages, closely closing

leaf after leaf, an army of tiny hermit creatures—

Frankenstein splices of insect shells, fragments of lashes,

fibre and skin.

To sweep it would be merely

to cast a new dance of twirling particles.

It is exhausting, keeping things clean;

exhausting

to warm the stove, to watch the hours

unfurling

through the clock on the wall.

The sunflowers fade now; it is properly autumn,

bronze and darkening green.

Their time has been

and I collect the topaz petals, shrivelled slightly

as they catch on the carpet, the stacks of magazines.

September spreads its beautiful disease through the streets

as the leaves begin to fall, oozing soft fire,

the sweep sap of decay.

In the window, the sunflowers have lost their vigour.

They drop; their heads slump down,

defeated, as if shy at their deaths.

Their filaments wither, every yellow floret

sinks, crisp; a victim of gravity.

Every entrance to the room augments their sorrow.

We have forgotten the day we bought them,

or even where they were from.

There is just the slant of light, the green and ochre

smell of cooking, the smoke across the road,

and the knowing that probably

I will throw those flowers away tomorrow.

— 23/9/16

So Long, Marianne

(a story I wrote back in April, after a friend gave me two prompts: ‘railcard’ and ‘lonely’).

She found the railcard lying in a puddle. It was the case that caught her eye: its plastic glitter coating blinded her momentarily as she waited to cross the road. A single beam of sunlight had caught that glitter and Amanda knew it was for a reason. She knelt down to pick it up, wiping it clean on her jeans. The man standing next to her on the pavement eyed her warily as she examined it. The name on the card was Marianne Holbrook, and the picture, slightly blurred, showed a girl of Amanda’s age, with cropped brown hair and eyes rimmed thick with kohl and shadow, lips a deep rich red. On the flip side of the case was another card: a student ID, whose expiry date was last year.

“You should hand that in you know,” the man beside her said, interrupting her reverie.

“Yes,” she replied.

Amanda did not hand it in. She took it home with her and tried to go about her evening as normal. She put it up high on her bookshelf, next to the little cat ornaments her grandmother had given her as a child. She put the radio on, to make the flat seem less quiet. She boiled the kettle. She stood in front of the mirror, brushing her long thick hair. The jangly pop music seemed only to ricochet off the silence, intensifying instead of subduing it. Amanda tugged and tugged at her hair but she could not get the knots out. Tears of frustration sprung to her eyes.

She felt pathetic for crying. Her arms crumbled to her sides and she threw down the brush. The kettle began to whistle. Amanda burnt her tongue on the first sip of tea. She checked her phone but there were no texts; there had been nothing, now, for three days.

The following morning, she went out on her lunch break and got a standby appointment with a hairdresser near her work.

“I want it very short,” she said carefully, fingering the long strands of hair that framed her face.

“How short?” The stylist asked, lifting clumps from the lengths of Amanda’s hair and letting them fall again, as if she were trying to gauge how much her tresses weighed.

“Oh, a crop. A pixie cut.”

“Bold, huh?”

“Like Laura Marling. Very short.”

“I don’t know who that is honey. You sure you have the features for something that short? I’m not saying you have a big nose or anything but wouldn’t you like to look at—”

“No,” Amanda said firmly, “I want a crop. Please. I don’t care about dainty features.”

“Okay, whatever you want.”

It took an hour. Great wads of hair fell away past her shoulders as the stylist attacked Amanda’s locks with her scissors. She cut away in steady, hungry snips until all that was left was a ruffled mess, short as a boy’s.

“Don’t worry,” the stylist assured her, “it’ll look weird until I’ve wetted it and done the layers.” Another half hour and it was done. The blow-dry took minutes. Amanda blinked in the mirror and tried to imagine what she would look like with heavier eye makeup. Marianne Holbrook. The girl in the railcard photo, blankly staring, mysterious.

“Thanks.”

“It does look rather amazing,” the stylist admitted, surprised.

Amanda went back to work and everyone was so shocked at what she had done that they all forgot to reprimand her for being late.

“Very sexy,” her boss said, biting his pencil. Amanda felt hollow inside as she sat down at her desk. The afternoon stretched before her, empty and dark as an elevator shaft. She couldn’t wait to get home; there were things to be done.

That night, she took the glitter wallet off the shelf and carefully pulled out the two cards inside. She took the student ID and held it over the bin as she snipped it into pieces. The girl in the photo looked very young: she had shoulder-length hair, blonde, a shock of fringe and a lurid shade of lipstick. It hardly seemed the same Marianne as the one in the railcard photo. Amanda turned the railcard over in her fingers. She had looked it up online and discovered that it granted the user unlimited free travel to any UK rail destination. It was a mystery as to how this girl obtained such a privilege, but Amanda realised that it had fallen into her hands for a reason. Without the obstruction of fares, the whole of Britain opened up for her like some elaborate flower, ready to ooze its precious nectar. She googled train routes across the rest of England, Wales and even, with some timidity, Scotland. The red patterns spiralled outwards, running their veins lusciously across the green countryside, alongside rivers, canals, forests and coastline. She looked up towns and cities, high speed connections and leisurely scenic routes. There was so much to see that soon enough, Amanda could hardly contain her excitement.

She would take time off work to live on Britain’s trains. How difficult could it be? She would give herself up to the whims of timetables and route planners, to vague and uncertain destinations and journeys. There were some trains that ran through the night. There were stations with shelters that didn’t kick you out. If worst came to worst, she would tap into her savings and stay in hostels and cheap B&Bs. The whole while she would assume her new identity. She would be Marianne Holbrook. She would never be lonely.

She phoned up her work the following morning.

“Hello Gina,” she said, “can you tell Mr. Raymond that I’ll be gone for a few weeks?” Gina, the manager’s personal assistant, raised her voice to a shrill pitch.

“What do you mean, gone a few weeks?”

“Oh, I’m going away for awhile. My circumstances have…changed.”

“‘Manda—” She cleared her throat loudly. “I’m going to need a better explanation to give him…do you have a doctor’s note? Are you leaving? You’ll have to hand in your notice, there’s procedure—”

“Tell him I’ll just be gone awhile. He won’t mind. Have a nice day, Gina.” Amanda hung up. For once, she realised she did not care about procedure. She stuffed her phone back into the side pocket of her rucksack, and turned back to the window. It was partially open and a cool breeze rustled the bare skin of her neck, which felt deliciously naked without her long hair to cover it. April hadn’t brought many showers since it turned its first few leaves; in fact, the weather had been glorious. Outside the carriage window, the sky was a bright bright blue and the crumbling buildings that skirted the city gave way to fields which rolled over and over in verdant, romantic green. It took forty minutes before they were properly out of the city. Once the ticket inspector had checked her railcard, Amanda plugged in her headphones and listened to an old Cat Power album.

She had to change trains a few hours in. The whole process was far less stressful now that she had no fixed destination, no time constraints. Every hour was her own, and time itself did not matter. She sat on the cold station seats, trying to read a leaflet about a local whisky distillery that she had picked up by the ticket gates. People looked at her differently with her new hair. Girls glanced at her with lingering intrigue. Boys rarely noticed her, or else they had to do a double-take. Amanda wasn’t sure if these were good double-takes, or bad ones. She wasn’t even sure what the difference was.

As the station clock clicked to ten o’clock, Amanda checked her phone. Still no texts. And yet, why did she care? She had already told him it was over.

She travelled up and down the whole of the UK. She spent a day in sunny Brighton, looking out to the limit points of this country she called home, at the sparkling lights at the end of the ocean. In the nightclub that evening, she found herself dancing to Eurotech, face gleaming with metallic makeup and sweat. A stranger slid his hand to the back of her neck and she let him kiss her amidst the flashing lights and thumping music. His mouth tasted chemical sweet. Outside, gasping for breath on the beach pebbles, she wondered whether this was something Marianne would do. Take things on impulse. Treat people like shadows, passing through your day, swelling, shrinking, disappearing. Somewhere in the darkness, the sea whispered its history of secrets. The city withheld its judgment.

Back up the country she travelled. She skirted round London, past the rolling hills of the South Downs; past Basingstoke, Luton, Milton Keynes. The changing accents haunted her with their shrill cacophony. She slept in a Travel Inn that night, washing her hair with the complimentary lemon shampoo that smelled good enough to eat. It was a very lonely motel: all the corridors were empty. Even the cleaners drifted along like ghosts, never looking up or smiling. She caught herself checking work emails on the WiFi and had to force herself to stop. She took a small vodka from the minibar.

What would Ruaridh say to all this?

Night after night, the meaningless names drifted through her mind. She had seen so many towns and cities now that she had lost her sense of what made each one distinct. England became unreal, this vast, impenetrable stretch of motorways, train tracks, telephone wires and suburbs. The crowds and the people and the buildings were different, but each time she felt the same. She did not feel real, floating aimlessly down street after street with no direction or purpose, nestling into the armchair of yet another Starbucks. Amanda told herself she was just exploring.

Sometimes she found herself wondering what Marianne had studied at uni, what she now did for a living. She imagined her, all cropped hair and smoky eyes, leaning over a desk at some sleek fashion magazine office. She pictured her in a court of law, sharp in a suit, scrawling notes. She saw her lifting weights at a gym after a hard day at the bank. She saw her serving tables at a classy restaurant, drinking martinis at some downtown bar. These were all possibilities. Marianne was made of possibilities.

On the train from Birmingham, disillusioned with cities and their grey array of indifferent buildings, Amanda managed to bump her way onto the first class carriage. This was something Marianne would do, sleek and easy like her hair. It was simple enough to turn tricks when you were less self-conscious. She brushed her fingers over the plush seats and nestled into her headrest. A skinny man dressed as a waiter came round with a trolley bar and every time he passed, Amanda ordered another Bloody Mary. She licked her lips as he stirred in the celery, the other passengers impatiently waiting.

Three drinks in and she kept dialling his number on her phone.

“Come on Ruaridh, pick up,” she hissed. People around her were staring. She was an odd sight on their carriage, with her little white belly poking out of her cut-out dress. She dialled again and again and of course he did not pick up. It was three months since they had last spoken, since she told him they could no longer be together; three months since the silence started, since she cut herself off from the world. And yet, a fortnight was all it took. Two weeks since her first outing as Marianne Holbrook.

“You never tell me what you want, how I can make things better for you.” Is that what he said to her, or did she say it to him? It hurt that now she could hardly remember; there was a time when she thought she had the words they exchanged engraved in her soul. Now it seemed, they slipped away, easy as the faces left melting on the platform as the train pulled out of the station…

She was in Leicester, Nottingham, Coventry. She found herself addicted to all the stations, their absolute sense of space devoid of place. In the stations, everyone could be anyone. She liked the dull parquet floors and the green painted railings and the matching uniforms, the logos and slogans, the slow and constant stream of announcements. People coming and going, bags and suitcases rolling along, teenagers moping around by the Burger Kings, waiting to be asked to move on. In so many ways, each station was the same. Aside from the stacks of leaflets advertising local attractions, it was easy to forget where you were. Each one was a kind of anywhere. Accents blended and clashed and Amanda felt like she was in some way everywhere in Britain at once: the stations were just another node in the network of cities, people and identities. The same chain stores brightened her view as she stepped off the train. She started buying the exact same things every time: the superfood salad from M&S, the Wrigley’s gum and magazines from WHSmith, the treat bag from Millie’s Cookies, the almond butter hand cream from The Body Shop that depleted so fast, what with the air conditioner on the trains drying out Amanda’s skin. It was so satisfying to follow a pattern.

“What’s your name?”

It was the day that somebody broke the pattern. She was hovering by the ticket gates at Preston station, clutching her railcard and hoping to catch the northbound train.

“Am-Marianne,” she found herself saying in reply. The stranger was an old man, laden with a heavy-looking rucksack.

“Ammarianne, it sounds Greek or something.” Amanda bit her lip.

“I’m Jim,” the man added. He wore an old tweed cap and had a vaguely Scottish accent. She did not know what to say, what he wanted from her. She thought about what Marianne would do, the possibilities that the interchange offered for experimenting.

“It’s actually Marianne,” she said.

“Hm?” he was checking the screens, squinting to see his train time.

“My name. Not Ammarianne.” She forced a smile.

“Where are you heading then?” He gestured towards the board of departures and arrivals.

“Well, somewhere up north I think,” she replied vaguely.

“Glad to hear it,” he said, “me too. I’m a fish out of water here. Scotland is a good place to go for the lonely.”

“Yes.” She hadn’t planned on heading that far north. Carlisle had been her limit point.

“Oh. Well,” he hauled his bag from the ground. “That’s my train. Better hurry.”

“Bye,” Amanda whispered, watching him stumble through the ticket gates. Just before disappearing around the corner of the platform, he turned and shouted out to her.

“So long, Marianne.” She could see that he was grinning and she did not understand the joke. What would come upon a person to make them approach a stranger like that, for no reason other than to say hello? It was so foreign to her, that kind of politeness, that pointless brand of interaction. Stepping on her own train, the thought of the man lingered in her mind. So easily he had broken the silent contract of anonymity which seemed to govern the stations. Was this something she could do too?

The thought of talking to strangers made Amanda feel powerful. She knew, then, that Marianne was the kind of girl who had no problem letting her guard down.

They had thrown her off the train where she sat in first class. She had drunk one too many Bloody Marys and was slurring nonsense at her fellow passengers, bits of celery still stuck in her teeth, tomato juice stinging her lips. It was difficult for her to recall now, but she had more than once broken the silent contract herself. She had not so subtlety propositioned a businessman, declared to everyone an undying love for her ex-boyfriend, blithely told a woman that she should eat less of those chocolate bars because they were making her fat.

“But don’t worry,” she had droned on, “look at the state of me too,” she pinched a roll of flesh that clung to the skin of her dress, “I’m gonna lay off the cookies too once I get off this ride, once all this stops…” She had promptly vomited all over the polished floor and the conductor had to clear it up while the train was still moving and his mop bucket sloshed and then at the next station he escorted her to the exit, while everyone eyed her with disdain. She threw up again on the platform and knew that night she could not stay at the station. The world had clocked her for who she truly was.

The thing was to keep moving. She got herself to Blackpool on the bus and won some money on the slots. There was such a pure satisfaction in the click and spin of the fruit symbols, turning and turning. The leap in her chest when they matched up: three bright sets of cherries. That night she watched the boats twinkle over the bay, the carnival music blaring wickedly from the Pleasure Beach. There were couples everywhere, locking lips as the blue lights shone down from the rides, as the waves slushed gently on the sand, as the breeze whistled in the cold dark air. Leaning over the pier, Amanda ate fish and chips drowned in vinegar, hoping to cure her hangover. Her phone bleeped with a message from her mother: Hope you’re OK honey. Guess who I bumped into in town today? xxxx

Amanda hardly wanted to know. It was probably an old school teacher, or some pal that Amanda hung out with in primary school.

Who? x The grease from the fish supper made thumb prints on her phone.

Ruaridh, of all people! and we thought he had gone away!

Ruaridh?

I don’t know how long he’ll be here for. He was asking after you.

Not that he ever texted her back. Not that he ever really tried to touch base anymore. She flicked through her messages to him:

I’m sorry. Can we talk?

Please can you answer the phone. I want to explain.

I miss you. I’m faraway from home and I still miss you.

Call me back.

Please Ruaridh, call me back.

It had been so long since they had talked that he had started to appear to her only in the abstract, the name on her phone a source code that might unlock some pattern from the shards of memory resting useless in her brain.

And yet he had asked after her; he had spoken to her mother. Had he perhaps changed his number? Was his old phone lying, battery dead, at the bottom of the desk drawer where he kept his protein shakes, his condoms and badges and passport?

She thought of those texts, drifting on through the ether, directionless as she was. Town names and station signs blurred into one. Even the old-fashioned stations seemed the same, with their pretty red brickwork, their giant clocks and gleaming phone boxes. The whole journey she had been going nowhere, but all the while she longed for one destination. Was it him? Could it possibly just be him? The city she had lived in all these years seemed so distant. It felt impossible, the prospect of just going home. In the carriage with the tables, the ragged newspapers, the empty bottles and coffee cups, she was leaving her old life behind.

The train was so quiet. A little girl was licking crisp crumbs from her fingers, staring at Amanda across the table, eyes wide and oddly fearful.

What does she want, what does she want?

She was in Scotland now at last, passing by sparkling lochs and pine-covered mountains. She hadn’t planned on coming here. The train just kept going, rolling on slower and slower, and Amanda had lacked the energy to change her route at Carlisle. Scotland seemed like the end of the universe. It was easier to stay on the same train, easier to let the world direct her like this. This was the land of accents she could hardly understand. Silvery land of wilderness and silence. Everything enveloped in mist. Everything cold, mysterious, romantic. The train tracks wound dramatically round mountains, farmland, fields pregnant with the summer harvest. Sometimes the mist cleared and Amanda would glimpse patches of bright sky. In the past few weeks, the evenings had grown longer, so that now at half past eight the carriage was bathed in a soft yellow light. The grass that Amanda could see from the windows was a kind of supernatural green, so vivid it was difficult to look away. The fields stretched out into endless hills, lush with ferns and trees, fluffy white sheep and even the odd telephone line. Often they passed little cottages and farms, or villages speckled with lights that twinkled through chimney smoke. There were very few houses in the mountains; the train was disappearing into somewhere very remote. Surely by now they should be in Glasgow, or maybe Edinburgh? She couldn’t remember which one came first. All that surrounded her now were the mountains, snow-capped, rust-coloured, rocky, sometimes a deep and sinister green.

It struck Amanda that the mountains reminded her of her father, who used to take her up to the Lakes sometimes when she was young, forcing her to learn the maps even though the sight of all those squiggly lines and symbols made her dizzy, more disorientated than she was before. He made her traipse across acres of countryside, reciting his favourite segments from the guidebook, stretching out the hours with his constant narration. Reviving himself with cider at some farmer’s pub, where the locals would stare at them suspiciously as Amanda sipped her lemonade and the whole while her father never noticed. It was in the summertime, two years ago now, that he died.

Nobody talked about it. Amanda’s parents were halfway through a messy divorce when he discovered he had cancer. It had all happened so fast. The appointments, the vomiting, the weight loss – the transition into anonymity and sickness.

At rockbottom. Please call me, even just for a minute.

She hated herself even as she typed the message. All I want is to hear your voice. The thought of all those pathetic unanswered texts piling up on his phone made her physically sick. The train churned on, its sluggish rhythm another source of her nausea. The only messages she’d been receiving were voicemails from work, telling her she’d missed deadlines, meetings; telling her they were disappointed, telling her not to bother coming back.

In the cracked glass mirror of the carriage toilet, her reflection looked strange somehow. There were new shadows etched under her eyes, greenish as some disease. Little flecks of red that veined the whiteness round her irises. She realised she hadn’t slept more than three hours a night for weeks.

She thought of her father, emaciated, pushing a supermarket trolley, his fingers gripping the bar so hard you could see the tendons round his knuckles. The smile he forced as she shoved bottles in the trolley was grotesque and strange: a Cheshire cat grin smeared upon those hollow cheeks. He was buying her vodka because she was going to a birthday party, because she was not yet eighteen – a clandestine mission concealed from her mother. She thought how he would appear then to a stranger, vodka rattling in the trolley, this gaunt figure swathed in scarf and overcoat, incongruous against the mildness of that May.

There were secrets in these hills, Amanda thought, that nobody knew. Such endless stretches of greenery, pure as the wool on a lamb’s back; stretches which no man had touched with his brick or chisel. In the hills, there was a sense of possibility; in the hills, you could be free.

This freedom was quite terrifying.

The train had slowed as it finally approached a new destination. Nervously, Amanda fingered the plastic coating of the railcard with Marianne’s face on it. She was tired of always playing a role. It drained you, the whole process of never revealing your true name, spinning webs of lies to perfect your anonymity. Brushing past strangers and missing out on meaningful conversation. Out of a picture she had fashioned an entire existence, but now this identity felt crude and shallow. She was tired of staring out of windows, tired of flirting with strangers. She found herself missing her mother, the 24-hour shop down the road, the memories that haunted her home in Bristol.

She disembarked from the train in some small town, the name of which she couldn’t even pronounce. Everything was tiny, shrunken somehow, like a toy sized version of reality. Standing outside the town’s single newsagent, Amanda checked her phone. There was no signal whatsoever. She walked round and round the village, but to no avail. She knew then that she had completely left civilisation behind.

This was probably the loneliest place she had ever visited. Her father had never taken her somewhere like this: his favourite destinations in the Lakes were the comparatively bustling towns of Ambleside and Windermere. Tourist hotspots with ferries and buses and trains. Here, all the pretty streets, with their flower baskets, their plant pots and cobbles, were empty. Only the humming bees provided company. It was, perhaps, a town that time had forgotten.

Amanda realised she was starving, that the pains in her stomach meant something. She came across a tiny shop which seemed to be the only amenity in the village. The sign in the window said: “No More Than Two Children At Any One Time”. She stepped inside and a bell tinkled. The woman behind the counter greeted her in a thick accent. It was not like the Scottish voices on the radio or telly. The shop was so small that Amanda had to duck her head the whole time as she looked around. There were only a handful of aisles, shelves half stocked with off-looking bread and chocolate bars and tin after tin after tin of beans. At the counter there were a few fresh rolls and some fruit. Amanda bought what she could and thanked the woman.

“What brings you to these parts?” she asked, noticing Amanda’s conspicuous Englishness, the Queen’s face on the £5 note she handed over.

“I don’t know,” Amanda admitted. “I guess I’m looking for something.”

“Well, you might find it here. Folk have found worse in this village.” She smiled wryly and the wrinkles of her face creased up like the sand folding in patterns left by the tide.

“Oh?” The woman handed Amanda her change but her lips remained shut tight. Outside the shop, the weather had changed ever so slightly. There was a faint breeze stirring in the surrounding trees. The village seemed to be in a valley, protected from the harsher elements. It was a miracle there was a train station at all here – probably it was some relic from the Victorian era. Maybe there was a coal mine here once, or maybe the roads were in such bad condition that even the buses couldn’t get out this far into the wilderness. Amanda had the vague sense that she was in the Highlands, but she couldn’t be sure. The air had a thick moisture to it, a soothing texture to every breath she took, to the smoke that rose from cottage chimneys, the clouds that curled round the snowy tops of mountains.

She wasn’t quite ready to eat yet, though she was very hungry. She wanted to explore every inch of the village first. There were a handful of tiny winding streets, windows in miniature, house after house with Gaelic names etched on the door. Wild cherry trees flowered with late blossom round a square, in the centre of which was a war monument. Amanda stood and read all the names of the deceased carefully. Everyone seemed to have the same names: John and William and James. She touched the thick grey stone and its coldness seemed to spread through her bones. All those people, whose minds and bodies were lost in the turmoil of something far larger than themselves. The memorial seemed the only thing, apart from the ancient railway line, that connected this place to the outside world.

Ruaridh was a soldier. His job was to fight in whatever war they sent him to, to follow commands with cold precision, to give himself up to the mechanisms of higher forces. He had been in Iraq when Amanda was still at school and Afghanistan when she took night classes in college, serving coffees in Starbucks during the day. This whole other life had washed over him, while she remained at home, slowly growing, mostly staying the same. He had seen things he could never explain to her.

I miss you. I’m far away from home and I still miss you.

Perhaps his reticence was worse than hers. Perhaps he was the one who was truly unreachable, the one who could never match her in their silent exchanges beneath the sheets. She remembered the way he used to shake with nightmares, though denying them upon waking. It could’ve been his name, up there on a monument like this. Only no, because soldiers these days didn’t fight for glory, not like the old ways of valour and poetry and bravery. These days, even more they did not know what cause they were fighting for. They were just sent away, hardened with protein bars, coldly dished therapy and standardised training. She thought of the muscles in his neck, quivering as he spoke. Despite the strength of his body, it seemed all the time like it might snap, like the stem of a rose.

A photograph from the news: skinny, doe-eyed children, the reverberating dust of explosions, debris flying through a colourless sky. Soldiers in their khaki uniforms, praying for this world that they had not yet had time to properly love. For this world they might lose.

She remembered kissing him for the first time, in his mother’s living room, while they watched a black and white movie. The sound turned down, the whisper of their voices rustling the air. The walls would still contain those voices. Her fingers brushed the cold marble setting of the monument. Youth and innocence. Was that all that love was worth? And what about war?

Was loneliness the reward for all she had taken the guts to sever?

She thought of the scarring on his arms, the swellings of all those magenta welts which flowered outwards in jagged patterns, not unlike the etched textures of tree bark, both coarse and strangely smooth. The burns he had suffered were some price he had paid, his dues to the people he lived and fought for. Sometimes he would lie awake at night in pain while Amanda rubbed them with expensive oils and honey. She would watch his eyes close before the tears could leave them.

She turned away and the wind picked up and stirred the trees, shaking fistfuls of cherry blossoms from the branches, swirling them in the path with the shrivelled daffodils and the silver gravel. Some of the blossoms settled in Amanda’s hair. She walked away, past the church, following the tinkling sound of a river. She sat on its mossy bank and ate her apple, watching the midges rise above the water, spiralling in the gold light playing in the reflections of the pines in the river. Afterwards, her mouth felt sour as her soul. She wished she had cigarettes. She looked through her texts.

At rockbottom.

At rockbottom.

At rockbottom.

Three times she had sent it. Three times, and no reply.

She pictured herself, tied to the stir of the riverbed, pulled along by an unseen current. She would let it drag her where it willed, battering her on the sharp stones.

Somethings you just have to let go. Her father, whose ashes they scattered from Friar’s Crag, looking out upon a brilliant body of water, the light in the sky the colour of indigo as she watched her mother tearfully smile her final goodbye. The wind in the pines, the light on the lake.

Somewhere, Ruaridh would have stood among dust and chaos, a gun in his belt and his heart encased in a golden cage. In sparse Internet cafes, he would have written all those emails to her, sent her pictures of the crumbled houses and the desert. From this lush valley of greenery and quiet, it seemed another planet. She realised, then, that she was so many people. She wasn’t just the Amanda that maybe he had loved and grieved over and then ignored. She was the girl who would always mourn her father, who would long for summer afternoons in the Lakes; for the taste of ice lollies, for the breeze on her face. She was the lonely employee, biding her hours in her stuffy office. She was all these Amandas. But she was also Marianne: this monster who had burgeoned from a picture, larger than life, a figure of surface and depth, past her expiry date, readymade to inhabit. She had built this person from nothing but a picture, its plastic gloss the surface foundations. She knew, then, that she had the power to put herself back together.

I want to explain.

The midges danced on the water. The clouds moved overhead, the gloaming settled its purple shadows around the pines.

She no longer needed him to remember. Probably he was broken too, broken beyond her control. He would be back for awhile, but the call to leave would always drag him along again. War was, in a way, another kind of travelling. She did not crave the same excitement, the same desperate thrills of horror and danger that lay in the army; but still it was the impulse for movement that drove them both. She saw that now. They were both trying to escape the same lonely feeling, the hollowness that gnawed out from the bones that once held them up, that once fused their connection to the land and earth. To each other.

She caught the last train out of the village, finishing the last of her picnic. She watched the river’s silent starlit glitter stretch along the valleys, turning round the hillsides. She waited for her phone to regain its signal. She knew when it did, she would text her mother back at last: Tell him I’m fine.

And then she would delete his number from her phone.

And later, when she fell into sleep, she finally realised what the old man at Preston station had meant when he bade her goodbye. What it was he was quoting. The rich deep baritone of Leonard Cohen drifted into her mind and she remembered, she remembered. A song her father used to play on Sunday afternoons, smoking illicit cigarettes from the bedroom window while her mother was out getting the shopping.

I’m standing on a ledge and your fine spider web

is fastening my ankle to a stone.

And the chorus came to her, easily as sleep did, easy as the loneliness that now she embraced, languid and happy; as easy as the slow tug of the train that would take her who knows where, that would link this life and this self to the next one and bring her always some fresh memory that was better than home:

Now so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began…

Other Echoes Inhabit the Suburbs

The soup tasted pretty gross, but April kept right on eating it. For one thing, she couldn’t bear letting her grandma know that the heap of sugar she’d added ‘to bring out the flavour of the carrots’ had rendered the whole dish a form of cloying mush, as opposed to subtle teatime cuisine. Her grandma wasn’t all that good at subtlety. You only had to glance around the dining room, where they were sitting right at that minute, to know that Ms. Grainger (a return to her maiden name after the divorce) had a taste that lent itself to the gaudy and nostalgic, far more than the graceful and subtle. Along the mantelpiece, ugly china ornaments cluttered the marble surface (long overdue a good dusting); the wallpaper, a lurid shade of magenta, bore the same floral pattern it had done 30 years ago. As a child, April enjoyed peeling the corner of wallpaper behind the headboard of her bed, leaving a gape where the plaster underneath revealed itself like a blank and secret canvas. On that surface of plaster, April had written something special, eight years ago, when she first moved into her grandma’s home. The day after her parents died. It had been a long while since she’d checked if it was still there.

Despite her constant culinary failures, Ms. Grainger loved to entertain. She ran a competitive bridge club, who every Thursday traipsed through her door and gambled their pensions away round the dinner table. She still took great pride in her swimming pool, the envy of neighbours for decades now, even though she rarely (if ever) used it herself. Once upon a time, April had splashed around in that pool with her brother and sister, falling off her father’s shoulders as he waded her through the water, laughing. She had advertised her thirteenth birthday as a pool party, gathering all the kids from school round the kidney-shaped turquoise surface, drinking lemonade in the springtime sun. April was named after the month she was born in; when the kids used to tease her and ask her if that was why, she would nod, glumly, complicit in their derision of her mother. Her grandma always said it was a lovely name, but April herself was indifferent to its supposed charms. She realised that probably it was another ornament, a quaint and pretty reminder of a golden, bucolic past, when girls would flock round Maypoles in their white dresses. Maybe it hadn’t been her parents’ choice at all, but another idea cooked up by her grandma.

“Don’t you think it’s marvellous, how Jacob is doing?” Grandma Grainger piped up, pausing to look around the room for dramatic effect, though her only audience was April, along with old Marjorie from down the road. Marjorie, who was half deaf, took a good long minute to process the question before answering.

“Oh, what? Jacob, how is he doing?” Marjorie slurped a spoonful of soup, piercing her lips in mild disdain.

“He’s sailed through his third year of law school, that’s how he’s doing!” Grandma exclaimed, making no attempt to suppress her glee. “They say he got As all through his exams.”

“You must be so proud,” Marjorie said.

“Not only that, but he’s landed quite the internship, out in the city with a big firm.”

“Isn’t that wonderful,” Marjorie said, even more mechanically this time. She, like everyone else, had grown used to Grandma’s bragging, and had developed her own form of automatism to deal with it. April sipped her soup. She fixed her eyes on Marjorie, intent on registering every hint of discomfort that showed on her face. She too would be tasting, right at that moment, the same watery sugary sludge, the faint aroma of sage that cut brutally through the blandness of broccoli, potato, carrot. There was a pleasure in the knowledge that they shared this painful experience, dragging their spoons through the viscous excreta that Grandma Grainger had poured so obliviously into bowls for them.

“And how is Grace doing?” Marjorie asked, clearing the last of her bowl with one triumphant swallow. The question seemed even more forced than the act of putting soup in her mouth.

“Oh Gracey,” Grandma smiled, “she’s doing just fine. Very sensible girl.”

“Is she still wanting to…what was it, design buildings?”

“Yes Marjorie, she’s actually apprenticing as an architect right this minute, though I have high hopes for her and this man she’s living with. He works for a bank and is quite the charmer. I can see them settling down very soon.”

“Children, at her age?” Marjorie seemed mildly alarmed. She had never had kids, and though the subject was once taboo in the neighbourhood, she was now quite proud of the fact that the freedom had allowed her time alone to tinker with her paints, with trips to the seaside – to spend the evening consumed by soap operas instead of her husband’s ironing. Besides, some of the art shops in town had once bought her watercolours.

“Goodness, but wasn’t I firing them out at eighteen? Grace is 22 now, perfectly capable of handling a couple of youngsters.”

“Of course,” Marjorie murmured.

“A year younger than April, in fact,” Grandma found the need to point out, unnecessarily, as April stared glumly into her soup. There was no way of finishing the last of it. Already she felt a little sick. She swirled it round until patterns appeared about the sides, patterns which soon sunk back down as gravity sucked at the sludge.

“May I be excused?” she asked, having long ago perfected the strategic politeness of an obedient grandchild.

“Yes dear, what have you planned for the evening? I was wondering if you’d let Marjorie and I teach you bridge. You could whirl up quite the storm, with those maths skills of yours. I’d like to show you off on our Thursdays. I could do with some more winnings too, now that I think of it. Ethel really swiped us last week, eh?”

“I’m not sure you need maths skills to play bridge,” April said quietly.

“Will you listen to this? The girl really cannot take a compliment,” Grandma retorted. “I’m just trying to involve you dear.”

“I work most Thursdays.”

“Oh well. You spend far too much time alone, it’s not healthy for a young woman. You ought to be more like your sister.” The cutting line. “She’s always telling me – on the phone you know – how much fun she’s having.”

“I’m going out, Gran, I’m going out.” She scraped back her chair and wandered upstairs to her bedroom.

“At this time of night? She must be crazy,” Grandma muttered, out of her granddaughter’s earshot.

“Indeed,” came Marjorie’s reply.

The house was so dark, mostly lit by old-fashioned oil lamps that were stuck to the walls. It was an ex-council house, which Grandma Grainger had spent most of her life trying to make look bourgeois. Most of the houses in the surrounding suburb had been knocked down, upgraded into gleaming new builds, replete with fresh pine surfaces and huge double-glazed windows. Grandma, along with a small handful of fellow residents, had refused this development and by some miracle they were allowed to go on living in their humble hovels. It was a good thing they did, because the new builds had driven the local house prices up considerably, pushing out many of her old friends. It was home now mostly to young families, who relished the picket-fence dreams sold to them in American movies, who wanted to cocoon their kids from the dangers of ‘town’.

It wasn’t just town that was dangerous though. April knew well enough that this house itself could be ‘dangerous’. Many times she had fallen up those creaking stairs in the darkness, had found herself privy to some sordid phone conversation between her grandma and a mysterious third party:

“Oh, a terrible thing indeed!”

“He’s quite the scoundrel!”

“You’ll never believe what she told me she found in his sock-drawer!”

“I heard they’re getting the police involved. A terrible mess, for certain.”

One thing April hated was her grandma’s tone of mock horror, her incantations of scandal. She had perfected it for all the local housewives, proving herself a key player in the steady circulation of gossip upon which the suburb depended. It was worse than Facebook, the way news got around, the way her grandma would dissect every last detail of her neighbours’ lives around the dinner table, while April stared into uneaten soup or peas or sometimes, on Sundays as a treat, ice cream. April deleted her Facebook a long time ago. It provided too many links to her past, reminders of times that were happier, sadder, or at least more complicated. It hurt, to get bound up in all that again. She couldn’t be bothered hurting anymore. She couldn’t help thinking it would be nice to delete real conversation as easily as she’d gotten rid of Facebook.

“Well I heard he lost his job at the call centre. Shocking, isn’t it?”

April couldn’t help thinking: if only her grandma had employed that tone, to deft effect, when her parents had died. If only she had talked to the in-laws, to April’s father’s family; if only she had been more understanding, less impatient with the lawyers. Maybe then, April would still have another family. As it was, Grandma Grainger was all she had. Jacob and Grace, in all their seeming perfection, were always too busy – out of reach, ploughing headlong into their respective futures.

April’s bedroom, like the rest of the house, hadn’t changed an awful lot since she’d moved in. In fact, her grandma’s kitten obsession had crept its way even in here, in the form of a cross-stitch concocted from a palette of lurid pastels, tacked to the wall by the window. It was a very small window. The carpet was a foul kind of jungle green colour, supposedly a fashionable compliment to the orange walls, though its chic shabbiness was no detraction from the massive stain where Grace (who shared the room with April as a teenager – they slept top-and-tail in the bed) had once spilled half a bottle of red wine. Despite sharing a room for those years before university, Grace and April were never all that close. Grace seemed to find April strange, asking her all sorts of weird questions, as if she were the big sister and not April. Have you ever let a boy touch you? Ever done drugs? Why don’t you ever text anyone, I never see you with your phone. Are you gay? In truth, April had never really understood her younger sister. Her life had always revolved around a carnival of minor dramas – breakups and hook-ups and clandestine phone-calls, which April would eavesdrop on at night, while she pretended to sleep – and the whole wanting-to-be-an-architect thing seemed nothing more than just another design for life that took its place among the rest. Grace had always had plans, always rattled on about some boy she liked, a handbag she was saving for, a class she was intending to drop or take up. They were as sure in her head as the bottles of alcohol she stashed beneath the bed, and as certain to disappear or deplete by the end of the week.

As for April, the whole concept of a ‘design for life’ seemed drastically elusive. She couldn’t quite grasp how some people were able to think into their futures, then spin out a ten-step plan about how they were getting there. She liked lying in her bedroom, listening to obscure classical music, staring at the ceiling, letting the percussion and the elaborate orchestration of instruments and melodies weave themselves into her brain. She had been to university, stuck at it for nearly a whole year, but it just wasn’t for her. The equations and quadratics came easy to her, but everything else had gotten her down. Halls were a drag, seminars were a drag, and getting out of bed in the morning was the biggest drag of all. Making friends seemed to require some impossible formula that nobody had bothered to teach her, and April had made herself content with loneliness.

The mirror in her bedroom always showed you as fatter than you really were. Grace had first pointed this out, aged fourteen, preening her face and frowning as she noticed the curves that she hadn’t noticed before in the old mirror of their parents’ house.

“You haven’t put on weight,” April had assured her, with careful sincerity. Puberty had been the elephant in the room for a couple of months now: April had filled out and sprung up like a runner bean, her feet had grown to an impossible shoe size, while Grace stayed skinny and small as a boy, as her grandma. She became very touchy about it, worrying about every pound she might put on, pinching at her stomach.

“Oh,” she sighed in reply, “yes, it’s just the mirror I think. See the way it stretches out like that? The glass is damaged or something.”