Dear pain,

That’s how the light gets in. Fractal emanations of screaming the dark is a luxury the dark the dark. I listen to the radio and a mother talks of her autistic child preferring the dark — thriving in it, coming to life.

We soft-light to protect the unsaid stories.

Our bodies twist in the dark and we make an inconsistent work of pain-pleasure. The mattress gives out: pools of blood, ink, sweat, coffee, sex. I feel better when the sun comes up and when the sun goes down, wine-dark. It’s what’s in-between that’s the problem.

I keep thinking about Fred Moten’s luminous correspondence, ostensibly between Andrea Geyer and Margaret Kelly:

My friend, I have discovered in the antagonism between my work and dead letter that the project returns as an amazing field and air of correspondence, a transgenerational lotion of breathing, a revue of breath, a general bouquet in the grace of your asking in friendship since the day we met, and our braiding and breathing of a correspondence that we are now and have been working together in the atmosphere of our comrades, that we literally breathe them as a kind of braiding, an insistence of revolt as garment, a tapestry for the touched wall of a spaceship we noticed on the way to school, that off dimensionality of the cloud from our perspective, which I want to say is real not graphed, which I want to say is both a function of, and still untainted by the terrible business of, the Dutch masters, so that it’s impossible to tell the top from the side, though there was some kind of emanation or emendation that we all saw as a smooth flatness, like a table the cloud prepared of its own accord, a spread platform for spreading our metastatic air, our beautiful, is ourreal.

Fred Moten, The Service Porch (2016)

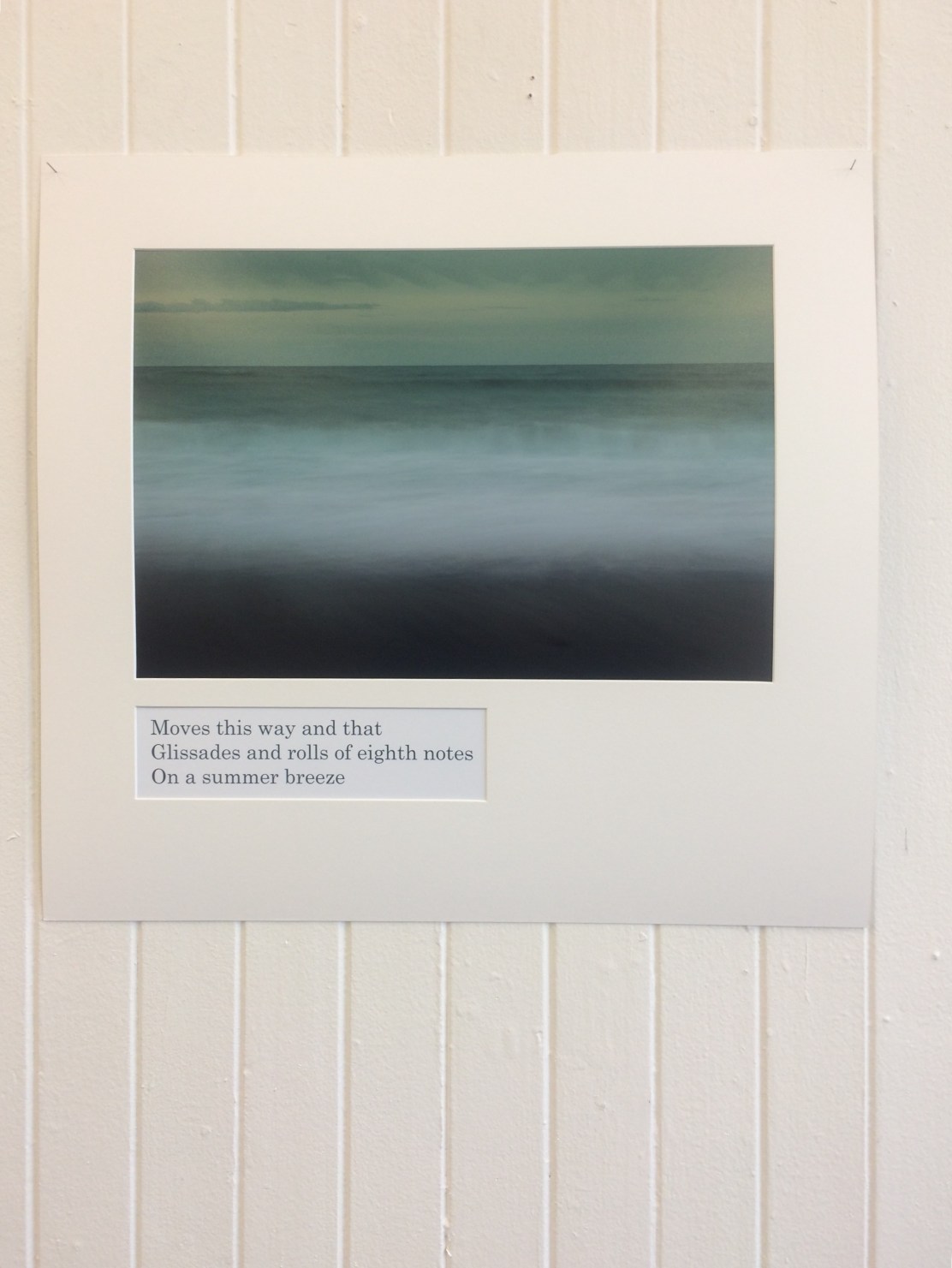

To make a pain of you, stop being a pain, I’d form a cartography of the nerves so rich you’d never know I’d outmatched the major scale. A map does not function in service of security. Anyone who has seen me read (and attempt to follow) a map knows this.

What is so gorgeous about the Moten quote above is its ph(r)asal longing: an ongoingness open to improvisation and constant sentence desuetude. Language like you don’t even need it, breathing all the same beyond what’s essential. Take this key. Braiding and breathing a coital somnolence of the body, twice rung out in language / only us leaving voice notes for what clicks pearls together, minor, deep in the distance.

Emollient longing of writing between pith and pronoun, what is prepared by the passing between. Our breath, clouds; mattering.

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

I saw the spaceship too. Didn’t you?

Intimacy, I told someone recently, feels like the opposite to what capitalism wants of us. Intimacy is worldsharing, ourreal, a grammar of humours, kisses and shibboleths. You know my pain and I know yours. We make a joke of it. What escapes serious talk but our serious dreams. So when we’re all in the gallery, we switch to our senses to make language-sense of ourreal, cellular vibe spread. It’s a room replete with the sonic ecology that is feeling all my fucking feelings (Clémentine Coupau): aka hook me up to ‘electronic components, dimensions variable’. The little paper lantern is a miniature version of my own IKEA lampshade. The problem with my IKEA lampshade is that I had to tear it a bit to change the lightbulb. I have a torn lantern. Magic hands. That’s how the light gets in. Paper = skin. Creamy light.

Aside from lanterns, the other homeware alluded to are curtains. Che Go Eun’s a hole in a boat and a deep hole is composed in collaboration with artificial intelligence. The artist inserted diary notes into an AI image generator which ‘transformed [their] intimate reflections and resulted in images’. Watercolour drawings were then made in response to those results, with the artist ‘reappropriating’ their ‘own feelings back from the AI’. This tension between creativity, data and predictive imaging results in a fascinating, speculative assemblage of arabesque, thorn and psychedelic colour. The nod to William Morris/Arts & Crafts reminds us of the collaborative handicraft that has gone into the piece’s imaginary and manifestation. Diary phrases such as ‘art nouveau’, ‘harder I am sinking’, ‘throw all my stress into the hole’ are woven into the fabric of these drapes which suggest both privacy and opening, light and shade. The work is gauzy. There’s a real street, a construction site behind it. Trongate: name as lozenge. What Moten says in the same letter-poem as quoted above, ‘a gauze of reckoning’. Threads, braids: stress, tension. I want to wrap the code-baroque of the fabric around my body like I’m a silkworm going in reverse, all the way back to its gross and sultry, larval conception. I keep hearing that the internet is just the unconscious. I see a bag of squishie candies in a vending machine and think: ugh, silkworms.

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

Back IRL, it’s raining with the pelting dreich that only a Glaschu April delivers, and I arrive at Trongate 103 having walked through Dennistoun listening to Elliott Smith. I’m not feeling morose; I’m just in touch with my feelings. As if they were tangible: animatronics, statuettes, pets. I’m still on a medication that holds such whimpering demands at just enough distance to be considered somehow ornamental — torrents no more. Once I would torrent my day in their favour. Let someone seed me. Now, I might choose to pick them up, put them back down, or smash them into oblivion. Let my soul have the architecture of a bleeding gate.

As I enter the exhibition, the invigilator says something about one of the objects we’re allowed to touch. I forget immediately what they say because I am greedy for colour and form, not meaning. So the whole time I am looking at the exhibits wondering: which of you may be touched? A finger trace of the curtains, time slider on video screen, glass surface of framing, kinesiology tape cut into bows and ribbons.

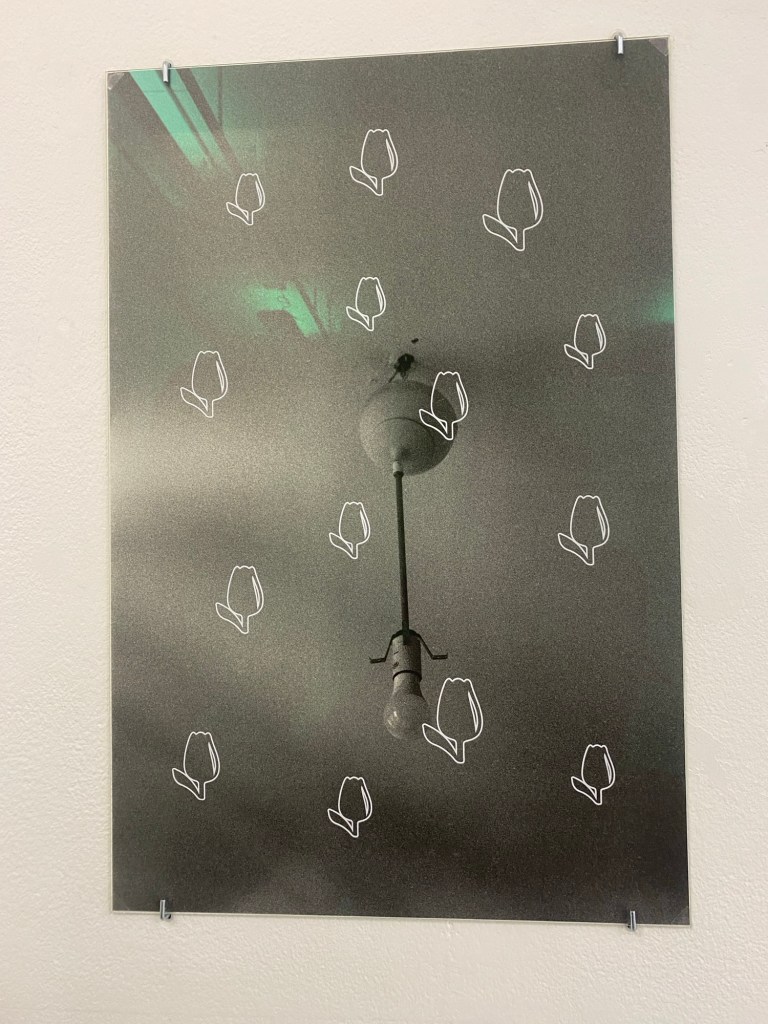

Touch is not in itself untainted. I am in love with Lafarge’s black tulips; their painful, precious tendrils.

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

Some people gave me advice

on how to do better: thirsty

in the flowerbed

for some aphids fed upon

200 ladybugs to eat/moult

more often than not they

would die as fast as any plant

blocked sunlight to pay

(dustfall / bonnie / smitten )

should the wind ever blow

you a raven

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

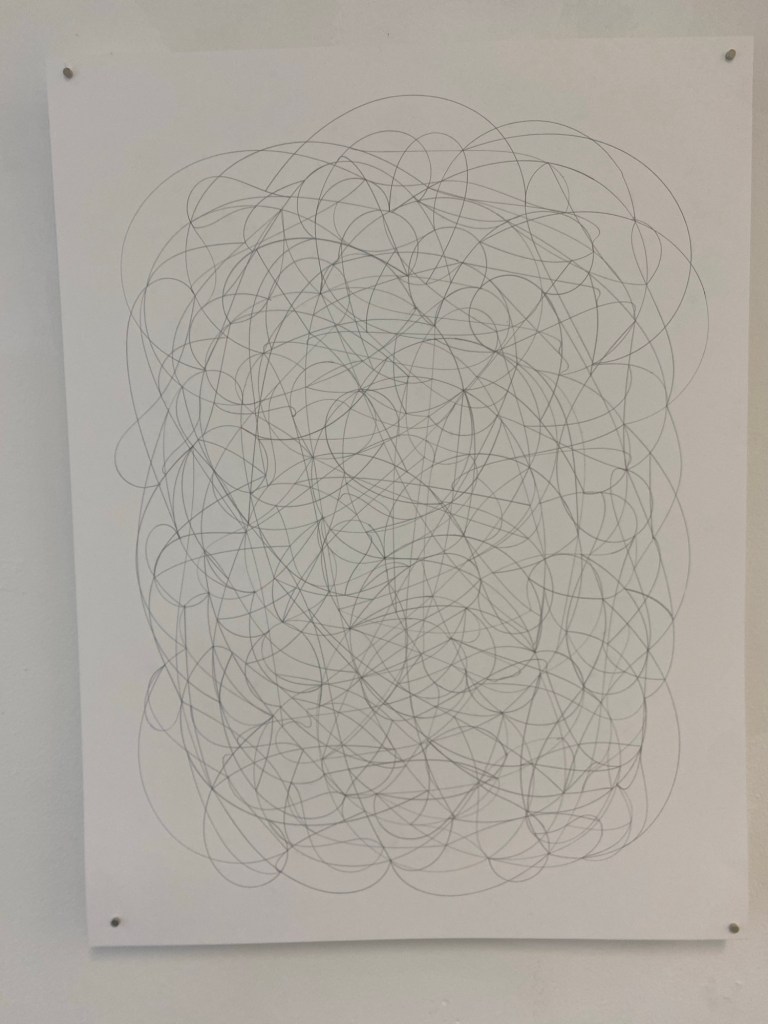

Mau and I try to diagnose the Mandelbrot set-seemingness of Lafarge’s watercolour fractals. The sequence ‘remains bounded in absolute value’. This is a beautiful phrase I find on Wikipedia. ‘It is one of the best-known examples of mathematical visualisation, mathematical beauty’. I could watch the little fractal gif forever like giving birth to myself over and over as a starfish with 7000 eyes & infinite narcissism. As it stands, that boundedness is a gate: pink, the colour of doll-flesh. I think of tentacles, elliptical phone calls, inflammation. We agree that almost all the art in the room is art that could be done on the phone. It’s not just about doodlecore but the intimate, desultory gesture of the line itself, and what’s on either side of it.

Not to get kinda kinky but the other day we were explaining ‘lucky pierre’ in the pub (because of Frank O’Hara the poet we all love and love most of all to discuss in the pub). In his ‘Personism: A Manifesto’, O’Hara talks about the poem in supplementary relation to people. Intimacy again. Sure, he wrote it while ‘in love with […] a blond’, which makes it all the more true and golden:

I went back to work and wrote a poem for this person. While I was writing it I was realising that if I wanted to I could use the telephone instead of writing the poem, and so Personism was born. It’s a very exciting movement which will undoubtedly have lots of adherents. It puts the poem squarely between the poet and the person, Lucky Pierre style, and the poem is correspondingly gratified. The poem is at last between two persons instead of two pages.

Frank O’Hara, ‘Personism: A Manifesto’ (1959)

As Moten’s poem from The Service Porch is framed between two persons, so the epistolary heat is folded into Personism. It’s not letters but speech itself that gets electric. So what Mau and I mean by ‘this is art that could be done on the telephone’ is perhaps something about how the work takes place in correspondence between two or more bodies. Lafarge describes her paintings ‘as a means of pure distraction’, made during ‘episodes of severe chronic pain’, ‘remote NHS chronic pain sessions’ and ‘in phone queues and conversation with Adult Disability Payment (Social Security Scotland)’. The trembling of watercolour is an apt form for the bleeding edges that connect the power imbalance of someone trying to get support and the person with the power to connect them to it. It’s the art of turning away, seeking psychic space, without letting total go of the line.

How often do we find ourselves at the gate, with no end of wanting to both know and not-know what’s beyond it?

Wrought/not I.

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

I love gates. I love especially baroque ones with curlicues. I grew up with a broken gate which soon got removed. What did we have to keep in, or shut out? It was black and gold and the paint flaked off very beautifully. You might describe it as ‘tawdry’. I probably have false memories about this gate. Sometimes the screech of its opening hinges my dreams. Lafarge’s gate might be a homophonic pun on ‘gait’ (and so referencing the debilitating effects of chronic pain on one’s ability to walk freely). The painting, titled Gate Theory of Pain (III), no doubt references Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall’s 1965 paper on ‘The Gate Theory of Pain’. In the words of Lorne M. Mendell:

The [Gate Theory of Pain] dealt explicitly with the apparent conflict in the 1960s between the paucity of sensory neurons that responded selectively to intense stimuli and the well-established finding that stimulation of the small fibres in peripheral nerves is required for the stimulus to be described as painful. It incorporated recently discovered mechanisms of presynaptic control of synaptic transmission from large and small sensory afferents which was suggested to “gate” incoming information depending on the balance between these inputs.

Lorne M. Mendell, ‘Constructing and Deconstructing the Gate Theory of Pain’ (2013)

The Gate Theory concerns sensory fibres, transmission cells and their respective levels of activity. The idea is that painless sensations can supplant and so quell sensations that are painful. The process involves a blocking (a closed gate) of input to transmission cells. When the gate is left open, the sensory input gets through to transmission cells and produces pain. An example of the therapeutic application of this theory is transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), massage, acupuncture, vibration and mindfulness-based pain management (MBPM). While gazing at Lafarge’s vivid watercolours, one senses that pain is not suspended in the art of painting so much as calibrated, channelled, short-circuited. We keep commenting on the bleeding edge.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, ideas of feedback loop, intimacy, daily life and relationality are also manifest. Feronia Wennborg and Simon Weins’ soft tissue plays with sound transduction to install a ‘lo-fi sound system that lives at the periphery of perception’. This installation of contact-based sound production manifests the pair’s ‘long-distance collaboration’ in felt space. Aniara Omann’s haunting paper baskets, plugged by family faces, makes a ragged philosophy of grief and panic. The raggedness betrays a struggle for focus which is played out through the woundful (I meant to say wonderful, but this works better) arrangement of loose paper, woven baskets, the sense of things cut, twisted, recycled. Omann describes wearing the clothes of their sister, who died: ‘If anyone complimented me on a garment I had inherited from her, I would say it was a gift from a family member’. In that sense, we could think about the paper baskets as fragile amphora for an archival underworld. The baskets are not perfect, machine-made. They retain the expressive and painful grace of their making. They are a flammable structure, woven from newspaper clippings, election flyers, prescription papers, envelopes, bills. What is it to find a way of wearing something? Wrap your troubles in dreams. Shuffle for sources. The difference is a question of agencies; and yet either way the gesture remains. The gift: it has to be infinite.

When someone says ‘hold the line’. Please hold the line. Please hold the handrail and take care on the stairs. Will you please hold? What’s at the end of that hold? I have been trying to get a medical appointment for weeks. They keep putting me on hold, hanging up. I phone up a doctor’s surgery which is based in a shopping mall at precisely 08:30, when the lines open, and immediately the lines (the queue) are full. How do I envision those lines? Swirling and spiralling around the postcode lottery of where we live, tangled and fizzing with people trying to find words for the pain they’re in. I think of my mum in lockdown, endlessly on the phone 500 miles away from the fact of trying to get prescriptions and medical treatment for my nan. It’s pretty mild for me, my current need to be on the line: among other things, fucked-up hearing, tinnitus, crackling I hear like static between the two sides of my skull. Sometimes a pleasurable hum in the morning, like ultrasound waves in the skeins of my pillow. On hold to the doctor’s office, you become a line. The hidden labour of the chronically ill is this beholden quality, the line with its insecurities. It’s getting thinner. There is no guarantee that the line will lead to something: its pulsing, throbbing insistence on being anything but spirogram music. The irony of disconnect. Give me a point; an appointment; a person at the other end.

Who would pick up the line would do so, of course, in the dead of night. In Stigmata: Escaping Texts, Helene Cixous writes:

It is the dead of night. I sense I am going to write. You, whom I accompany, you sense you are going to draw. Your night is waiting.

The figure which announces itself, which is going to make its appearance, the poet-of-drawings doesn’t see it. The model only appears to be outside. In truth it is invisible, but present, it lives inside the poet-of-drawings. You who pray with the pen, you feel it, hear it, dictate. Even if there is a landscape, a person, there outside—no, it’s from inside the body that the drawing-of-the-poet rises to the light of day. […] The drawing is without a stop.

Hélène Cixous, Stigmata: Escaping Texts, trans. by y Catherine A.F. MacGillivray (1998)

What I see in iNsEcurE (whose inconsistent casing recalls the long identifiers of medical-grade pharmaceuticals, the vowel-like howling insistence, the trembling name) are poets-of-drawings. The asemic work of line, layer and bleed is an avid supplement for writing itself. Who can write while in pain? Who’s afraid of the dark? Who’s afraid of the blank? It is in the night of writing, unnannounced. What is that invisible presence but pain itself? There is no ‘outside’ to pain, once you’re inside it. And yet the gate theory does imply a certain threshold. Relief bucks at the gate. Still, we draw from the well of it moving inside us. You can’t stop it. The appearance of the outside is only gauzy separation.

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

When I thought I had endometriosis and lived in the hormone torture of latent, duplicate pubescence, resulting from the long-durée of various quiet disorders, I wrote spiky little poems for a pamphlet called Cherry Nightshade. I didn’t yet know about the gate theory of pain but I saw all the poems in a dream_garden festering behind a gate. Well, more like a trellis. Ground cherries contain solanine and solanidine alkaloids: toxins which are lethal, and all the more lethal for their immaturity. Tart cherries have soporific qualities. I wanted sleep to envelop me in perfect velvet. My speaker was a jumping nerve, a shitty little internet silkworm.

What did I get from staring so long at the gate? I fell asleep on the line and the vine grew around me.

I love this exhibition for what it teaches us about art between bodies, how light interacts with feeling-colour, Moten’s ourreal in its total ambience, the drilling outside is part of that thrum in your skull, the way I love to look at my friends as they look at art, tulip mania, mourning vessels, the exquisite difference between red and pink, the meaning of panic touch, pain as the body’s great epistolary effort, fragility, attention’s relationship to healing, what it means to be gratified (if at all). I am grateful for the sharing of insecurity at the heart of the works, and for what they offer by way of being with pain. A bearing, a cloud platform, an intricacy. Standing at the gate.

‘•.¸♡ ♡¸.•’

Further notes:

- medical filigree

- acid yellowing

- mau touches a sound magnet

- ‘insecurity fuels consumerism’

- light source

- biofeedback

- neon bandage

- organelle ballet

- tesselate attentions

- the puzzle pieces do not technically touch

- go into the hole

- golden shovel

- ’emoji repertoire’

- give me a viable body

- ‘cast latex, apple seeds, sawdust’

- ‘I am still earning less than living wage through my art practice’

Becoming a line was catastrophic, but it was, still more unexpectedly (if that’s possible) prodigious. All of myself had to pass through that line. And through its horrible joltings. Metaphysics taken over by mechanics. Forced through the same path, my thoughts, and the vibration.

Henri Michaus, Miserable Miracle (2002) – quoted by Elísabet Brynhildardótti in the exhibition handout

iNsEcurE is open at Glasgow Project Room, Trongate 103, First Floor G51 5HD between 29th March-7th April. It is organised by Aniara Omann and supported by Creative Scotland and Hope Scott Trust.