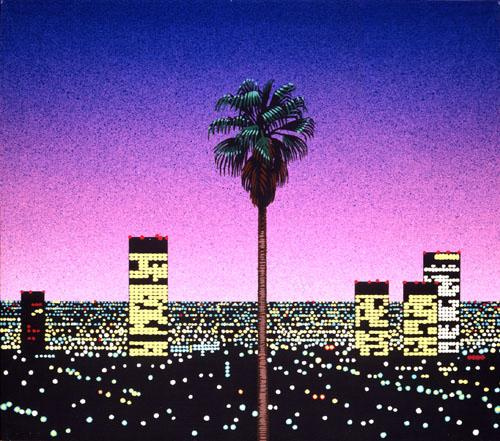

The resonance is a tinny vintage, anachronistic; tinselled with eighties synths and a vocal sample that never quite begins. That baggy voice, normally soft as milk, becomes jagged, inhuman. Creepily crystallised. Your aunty’s favourite easy-listening is stripped of all coherence and synthesis; the tacky detritus of Steve Wright’s Sunday Lovesongs repackaged for an ersatz world of sulphurous sunsets and crumbling metropolises imploding like the plastic dust of an Arizonan dead mall. Back to the dark desert highway, purple-skied and dripped in molten neon. This isn’t what you’d enjoy on a leisurely car trip to the drive through…Or is it?

Listen to : : :

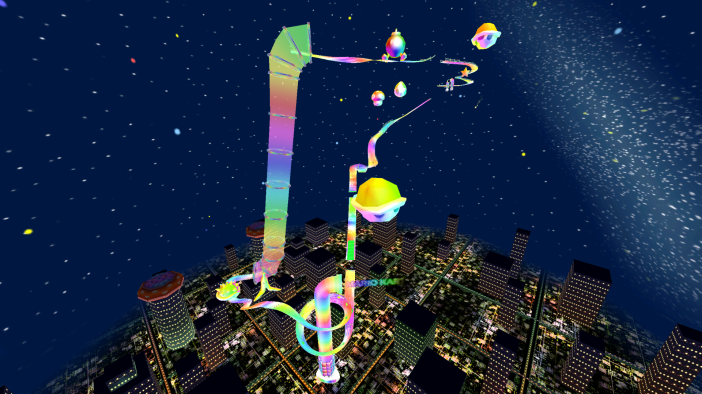

death’s dynamic shroud.wmv // I’m at the point in the level where the road narrows, curves, swirls upside down. Death is imminent. You can see the gloved fingers slipping a compact disc into the slot of a monster, borrowed straight from the architectures of Digimon. I’m thinking: Elizabeth Fraser’s sweetly haunting soprano (imagine being ghosted by the purest aural distillation of beauty); the chilled techno-ambience resurrected from the nineties. There’s heartbreak ahead. If you jump too far—and you will, won’t you—the space around you will glitch. There you’ll be, suspended in the space twinkles. An empty swimming pool. Climb into the cracks. Why is everything so gleaming, so white? I’m obsessed with getting back to matter. The music restores the filth, the glitch. There’s a vast acceleration of beautiful colour. The soprano grows warped, the orb-like contortions are glowing off kilter, off rhythm. The seven lumps of Galaxy chocolate I’ve just eaten melt sticky bits of sugar in my mouth, refuse to dissolve. They’ll coat my teeth like that.

Vapourwave coats your teeth. God knows how or why you should define it. It’s like cheap candy, utterly sugary but filled with mysterious ingredients, mystic chemicals from another dimension. One minute I’m being instructed about the start of a sequence (it’s the eerie echoes of a sci-fi style video game)- – – loading loading loading – – – and then trap style beats come bouncing slowly in, delayed as if strained through some outpouring of weird gravity. There’s a purity to some of it, which feels more like an original composition; the ambient atmosphere of something along the lines of Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works…There’s a sense of distortion, disorientation. Hyperreal landscapes lit in luminous pinks and purples. What’s that gleam, is it rain? Tokyo on a postcard, dipped in cross-processing chemicals, in violet acid. Then you’ve got a vague array of p a r a d i s e lighting up the screen. Palms and sand and cerulean sea.

As soon as you get attached to a sample, you’re away. Rarely does the beat resolve. You’re like, totally always stuck on the pre-beat. To the point that human expression becomes a technological fault, a beep, a burp. Sometimes it sounds like waves are being pulsed through your brain, blurred in a malfunction of some tacky machinery cooked up for a pulp movie of the nineties. Do scanners really look like that? Coated in rhinestones, bathed in pink. Some of it’s dreamier. Arpeggios of bell-scented keyboards (what do bells smell like? Not musty old church bells, but the sonorous chimes of noughties computers). Arpeggios climbing and climbing, dissolving, rising. A pop melody shining through. I’m in a rainforest of futurist skyscrapers, cloud-surrounded, everything drenched in pastel-hued pixels. It’s so serene.

Vapourwave. What a joke, an internet meme. Didn’t it die a couple of years ago?

I’m so confused. What is this monstrosity that’s eked itself into my life like a viral code luxuriating in my brain? At once disdainfully ironic, crass, tacky as hell; but also painfully sincere, nostalgic, full of a misplaced longing. The metamodern paradox of postmodern irony and modernist authenticity cooking up an endless loop of misplaced longing. I find myself thirsty for shopping malls from the seventies, for grotesque cups of Diet Pepsi, for the glossy pop of the eighties and the apocalyptic reveries of the nineties. I’m drifting through a city stripped of its glitz and left with patches of bright matte colour, refusing to reflect the glass through which dreams have appeared and got lost. I remember polishing a CD with the back of my sleeve, watching the lines of rainbows beam. Slotting it into a computer that hummed and whirred at my touch. I remember when technology felt somehow homely.

That comforting little Windows XP flourish, how friendly it was compared to the blasé boom of Apple’s triumphant C chord. Glitch, glitch, glitch. I pick the pixels out with my fingertips. The eerie keyed chords of MACINTOSH PLUS’ 地理 fill me with a sinister sense of urgency. It’s an entropic catastrophe of dissonance.

At the heart of vapourwave is a tension between the sweet and disturbing, between satisfyingly vacuous muzak and dissonant, deliberate glitching. This is related to its deterritorialising impulse, by which I mean (borrowing from Deleuze and Guattari lingo), the way it extracts and recontextualises some element of a thing, then placing it elsewhere in a different environment. Vapourwave is a sort of bulimic, abject, rhizomatic discourse. It gorges on the symbols of late capitalism (the glossy muzak and soft rock of the eighties, international brands like Nike or Microsoft, the aesthetics of corporate advertising and so on) and then expels them in a gross reinterpretation that seems to purge them of their original, seamless facade. It might be useful here to mention that sociologist/criminologist Jock Young (2007) once described late modernity as a ‘bulimic society’, where we are all (internationally) included in the dreamlike semiotics of the rich through the opulence and availability of global branding, advertising and popular culture, but increasingly we are structurally excluded from the means which would allow us to achieve such dizzying heights ourselves. This social anomie is jarringly rendered in vapourwave’s shameless embrace of corporate culture; at once poking fun at it but also monumentalising it in an ambiguous way. It’s by no means a didactic movement, but as Grafton Tanner tends to argue in his excellent book Babbling Corpse: Vapourwave and the Commodification of Ghosts (2016), it’s symptomatic of its times. The very poetics of vapourwave reflect the uneasy experience of being unable to escape the system, the uncanny effects of our perpetual cultural nostalgia—the celebration and denigration of late capitalist modernity and all its forms of post (post (post) post).

Outside of their usual contexts, corporate and commercial visuals (the vapourwave a e s t h e t i c) seem absurd, funny, strange, alienating. It hollows out the imagined ‘core’ of the brand and replaces it with a sort of free-floating lack of functionality, a disembodied eeriness. Chuck a logo in with a pastel-hued painting of palms and corny dolphins lifted from a SNES game and there you have it. Old Apple logos might be hovering over a pixellated ocean, waiting to plunge inexorably. Not only the aesthetics, but also the music itself, creates this sense of fragmented capitalism. Tanner talks briefly about the relevance of Derrida’s idea of hauntology to understanding the politics of vapourwave and this seems to me very astute. It’s the idea that the future is irrevocably haunted by the past; that culture and politics are also spooked with spectres from the past—from communism (Derrida’s book is called Spectres of Marx) to old technologies. It’s the idea that things are always-already obsolete, that there’s a sense of being itself as displaced and never quite fully present. It’s an ontology of difference, deferral, doubling, of objects which become ‘a little mad, weird, unsettled, “out of joint”’ (Derrida 1994). Derrida’s gloss on Marx’s analysis of the commodity-table gives us a sense on the ghostliness of consumer objects:

For example — and here is where the table comes on stage — the wood remains wooden when it is made into a table: it is then “an ordinary, sensuous thing [ein ordindäres, sinnliches Ding]”. It is quite different when it becomes a commodity, when the curtain goes up on the market and the table plays actor and character at the same time, when the commodity-table, says Marx, comes on stage (auftritt), begins to walk around and to put itself forward as a market value. Coup de theatre: the ordinary, sensuous thing is transfigured (verwandelt sich), it becomes someone, it assumes a figure. This woody and headstrong denseness is metamorphosed into a supernatural thing, a sensuous non-sensuous thing, sensuous but non-sensuous, sensuously supersensible (verwandelt er sich in ein sinnlich übersinnliches Ding). The ghostly schema now appears indispensable. The commodity is a “thing” without phenomenon, a thing in flight that surpasses the senses (it is invisible, intangible, inaudible, and odourless); but this transcendence is not altogether spiritual, it retains that bodiless body which we have recognised as making the difference between spectre and spirit. What surpasses the senses still passes before us in the silhouette of the sensuous body that it nevertheless lacks or that remains inaccessible to us.

(Derrida 1994)

Vapourwave, of course, exploits this ‘ghostly schema’ of consumer objects. ‘Woody and headstrong denseness’, the sheer materiality of the thing is ordinarily supplanted by its mystical, transcendent value as a commodified good or brand. When we think of Nike trainers, rarely do we care for their actual material structure; usually it is the symbolic resonance of the brand that captures us. In Vapourwave, materiality comes back, vicious and strange. Fredric Jameson laments the way that postmodernism presents us with a meaningless concatenation of cultural nostalgia, often without context—BuzzFeed’s noughties nostalgia lists perhaps being a case in point. Vapourwave takes this ‘out of context’ randomness and runs with it. Art objects, textures, corporate iconography and screen-saturated colours combine in a collage of irony and contrasts. The mishmash quality of the vapourwave aesthetic lends it to easy manipulation and re-creation. This is the DIY ethic of the movement, its impulse towards constant theft, the cut and paste fun of sampling, the wilful shredding of distortion which creates a contemporary rendering of William Burroughs’ literary cut-up method or the random-making ‘recipes’ of Dada poetry, as described by Tristan Tzara.

Now, the effects of this mixed-bag of internet treats aren’t just weird and humorous, but weird also in an unsettling way. The samples become points of focus in a manner that strips away the normal cultural values of the original song; the easy soft-rock of the eighties becomes haunted with lo-fi feedback and interruption, compression and echoes. It sounds like it’s being heard through a cave or the underwater atrium of an abandoned mall, after the apocalypse. One of vapourwave’s most prominent releases to this day remains Macintosh Plus’ Floral Shoppe (2011) and on this record the production warps its soul music with a surrealist synth-driven dreamscape, in which R&B beats become slow and trippy and human voices are dehumanised into drawls and robotic calls. Often a sample starts but never resolves its line, constantly stumbling over itself. Tempos are spliced and no song follows conventional structure, but instead runs on repetitions, overlaps, interruptions; completely jarring changes in rhythm and key with no transition. Funk and soul from the eighties are no longer smooth and satisfying radio filler, but are turned inside out, their inherent weirdness exposed. Some of the highlights include ‘It’s Your Move’ by Diana Ross and ‘You Need a Hero’ by Pages. The effect of listening to this album is sort of like pushing a shopping cart round a supermarket and gazing around in wonder at the saturated pastels, the pointless products, the detritus of cluttered consumer madness. Glitches, twinkles, the beats of unsteady feet. Random tannoy announcements like a call from some parallel universe, the underground, the flickers of the internet ether.

Tanner’s Babbling Corpse usefully makes a connection between the dehumanisation of human voices in vapourwave music and contemporary philosophical movements such as speculative realism and object-orientated ontology. Both movements share the fundamental rejection of correlationism (the dominant, anthropocentric idea in Western philosophy that views reality only in relation to and projection from the human perspective). Instead, they turn to the world experience of the nonhuman, the sentient and foreign perspective of matter and objects. They expose the contrived nature of our distinction between self and world, showing how we are world, entangled in a way that is inextricable and disturbing (Timothy Morton, for instance, points to the crustaceans that live in our eyelashes or the bacteria in our gut as examples of how we are the environment, rather than self-complete and separate beings). Vapourwave in some way manages to evoke this weird world of objects, at a level only barely accessible to humans. Its use of glitches and looped samples disrupts the ordering of people and things. As Tanner puts it,

Glitches interrupt our expectations while deceiving and annoying us. They undermine our notion of what the machine is supposed to do for us, not without us. In this way, our electronic machines take on lives of their own and appear capable of functioning perfectly well without humans – a complete transcendence into other-worldly sentience.

(2016: 11)

We might consider this in relation to Martin Heidegger’s (2008) idea that we only notice a tool as a thing when it stops working. A broken hammer suddenly becomes a strange entity in its own right, rather than just one chain link in the process of a means to an end. Chuck Persons Eccojams Vol. 1, for starters. The very name: Eccojams. It implies the jams are a product of this Other: the ecco, ecology, echo…The title derives from an old Sega Megadrive game called Ecco the Dolphin, an action adventure game which featured dreamy music and a very minimalist gameplay narrative. You made Ecco sing to attract and interact with other objects and cetaceans; you could evoke echolocation in order to unfold a map of your oceanic surroundings; you could call to special crystals (glyphs) which in various ways controlled Ecco’s access to different levels. There is a beautiful otherworldliness to this game, and not just because Ecco ends up at the City of Atlantis. It’s created its own mythology, and the emphasis on song (like The Legend of Zelda’s ocarina melodies, which initiate effects in the game) opens up the possibilities for a nonhuman conscious or logic. Music, perhaps more than language, has effects on nonhuman consciousness. At a certain pitch, it can shatter a glass, or cause buildings to rumble with bass. It opens up its own logic of cause and effect.

Hauntology, in a sense, is about being stuck on the loop of the end of history. Technology constantly dislocates our awareness of time and space, so that linearity is replaced with instancy, repetition and reiteration, the constant recycling of former styles and events. Repetition is uncanny partly because, as Freud argues in ‘The Uncanny’, it’s the structure of the unconscious. When we notice repetition, we notice how our whole psyches are built on the compulsion to repeat even that which is most traumatic to us. It also violates our sense of identity and experience as singular and unique (an idea that liberal democracy and consumer capitalism likes to perpetuate). Identical twins are uncanny for this reason, as is deja vu. We feel that the normal order of time and space has been distorted (this is of course made explicit in films like Donnie Darko, which deal with parallel universe theorems). Repetition is also uncanny because it suggests that things we thought were unique to a moment, imbued with their apparent transience, are actually lingering and potentially eternal. It’s unsettling to have the buried constantly disinterred and broken out into the open present. Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005) is a novel which explores the logic of repetition in relation to a trauma narrative in which the protagonist becomes obsessed with re-enacting events to the point of absurdity and violent conclusion. It’s that overlap of the real, where dreamlike remembrance meets actual performed repetition, that is the orgasmic satisfaction of the psyche.

Listening to vapourwave enacts this perfectly. We might start to recognise the songs from which these samples were drawn, but our recognition is distorted along with the samples themselves. The past floats uncannily into the future. Eccojams Vol. 1 drops its tinkling beats on a loop and the vocals from eighties ballads are stripped of their velvet and become mournful, minor, distorted. Inhuman, odd. There’s a sense in which our contemporary experience of reality in the face of apocalypse and pathological nostalgia is both dark and sweet. Morton’s branch of object-orientated ontology, dark ecology, perfectly captures this experience (in fact, in Dark Ecology (2016) he describes the process of dealing with this ‘grief’ as sharing the structure of a ‘dark ecological chocolate’). Vapourwave is at times incredibly saccharine, mapping itself through the cheerfully smooth loops of Muzak; but it is also jarring, dissonant, deeply unsettling. It takes dirty club techno, the complex tempos of intelligent dance music, and puts them through the cheap production of the GarageBand blender. Vocals echo like a broken tannoy machine. Vapourwave, as both visual and musical aesthetic, fundamentally opens an aural space in which past, present and future become a haunting echo chamber of one another. No longer is this the mere surface play of postmodern collage, but instead it’s the material manifestation of a specific cultural hauntology. As Tanner puts it, hauntology ‘is unlike Jameson’s pastiche in that it complicates the past (specifically, the past’s image of the future) in order to call attention to capitalism’s destructive nature as a subjugating force that only fools others into thinking it came to eradicate “history”’ (2016: 35-36). Capitalism is hollowed out, its signature brands become lost echoes in a vaguely recognisable, a hypnotically attractive yet alarming vision of our near-present future; blended with the figures of mall culture, the colours of early aughts internet webspaces and the abyssal possibilities of a Tumblr scroll.

I’m interested in how vapourwave re-enacts a different form of consciousness and how this might be ecological, even though the movement’s only obvious engagement with Nature as Such is through the proliferation of palms and potted plants that drift incongruously as consumer goods through some of its artwork. To get at its ecological sweetness, it’s like cracking open a crystal to see its lattice parameters (what a beautiful phrase), the places where the material cleaves (its lines of weakness), its cubic structure. The interplay between structure and embedded weakness is what motivates vapourwave; it contains its own failure, the undeveloped samples, the way a tiny snatch of a song is unfolded into a tranquil sequence of soporific, nonsensical sound. This is not music with a coherent logic. You look for lines and trends and vague traces of structure, but a song will become something more fluid and fragmented. Vapourwave’s material metaphors cannot be coherent; it’s at once free-floating, vaporous, seeping, gelatinous, oozing, splitting, cracking, choking, pulsing, dissolving. Hard matter, soft matter, chemical, vapour, waves and glitches and tiny explosions.

Sometimes, the structure is completely frustrating. On Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1, for example, the slowed-down, reverb-heavy sample from Gerry Rafferty’s ‘Baker Street’ repeats endlessly and never resolves itself into the next line: ‘another year and then we’ll be happy / just one more year and then we’ll be happy’. The twinkle signifies the glimpse of a transition and there’s a blip of the ‘b’ which should resolve into ‘but you’re crying, you’re crying now’ and yet here never does. Instead the song becomes an endless loop of implied futurity, the future conditional, ‘we’ll be happy’ that doesn’t get to complete itself but instead hangs. We’re taken out of time and left in this limbo. Here, the repetition isn’t soothing, it’s unsettling—mesmerising in a disturbing way. We question our longing for the song to resolve and before we have a chance it’s skipped to the next track. So we go back, search out the original version. Is it satisfying? Listening to Raferty’s original now feels weird in a way it didn’t before. It’s like this lost artefact from the past, spliced across the future ether rendered by Person’s eerie and hypnagogic album. While ‘Baker Street’ implies a specific place, now it’s thoroughly displaced, an effect of the internet’s rhizomatic possibilities.

As Morton puts it, ‘in order to have environmental awareness, one must be aware of space as more than just a vacuum. One must start taking note of, taking care of, one’s world’ (2002: 54). Ambient poetics disturb our assumed distinction between inside/outside, self/other; they show how we are entangled in a shared space of coexistence (Morton 2002: 54). Ambient music, in its sensuousness, its borrowing from the world—for example, by using samples of music concrète and field recordings from both nature and urban spaces—embeds us inside an environment in a way that is at once comforting and disturbing. It literally surrounds our senses. Brian Eno famously sets out a manifesto for ambient music by describing ambience as ‘an atmosphere, or a surrounding influence, a tint’, and ‘whereas conventional background music [i.e. Muzak] is produced by stripping away all sense of doubt and uncertainty […] from the music, Ambient Music retains these qualities. […] Ambient Music is intended to induce calm and a space to think’. As Morton puts it, ambient music as figured by Eno deconstructs the ‘opposition between foreground and background, or more precisely, between figure and ground’. In this sense, ‘ambience could be shown to resist the reification of space in capitalism’, ‘at once fill[ing] and overspill[ing] the ideological frame intended for it by the social structure in which it emerged’ (Morton 2001).

Think of it this way: could you get away with playing vapourwave in a mall or a supermarket or diner? Sure, it would ‘fill’ the space in one sense, but also exceed it, rendering all our cultural and material associations with this space uncanny and distorted. It would become a sci-fi space, a space displaced into the future. We would be inhabiting a doubled world, a doubled temporality. I tried playing Floral Shoppe in the restaurant where I work once (obviously when there were no customers) and the effect was actually very comforting. I felt like I wasn’t trapped in the familiar twenty-something existential limbo and instead inhabiting a plane of dreamlike contemplation, like the Rainbow Road level on MarioKart: Double Dash. I close my eyes and the scratched wooden floor spills out into a highway of colour; the tables I’m bumping against are bright yellow stars and fragments of unknown matter. I’m back in the supermarket, trolleys wheeling away from me and products falling off the shelf. I open my eyes and there’s the mirror and a reflection of someone that might be me, wearing a uniform, the chairs and tables flashing around me like holograms. I’m not exactly sure where that association sprung from (it’s been a long time since I’ve turned on the old GameCube), but I guess that’s the free associative impact of the music itself.

Like Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1782), vapourwave is about an experience of travel and movement without necessarily describing that movement itself. Crucially, the emphasis is on slowing down, on dwelling in a moment; a moment which is looped, repeated, pondered over, exhausted, reflected on. ‘I undertook to subject my life to a severe examination that would order it for the rest of my days in such a way as I wished to find it at the time of my death’ (Rousseau 2011: 24). Vapourwave subjects the e v e r y t h i n g of capitalist late modernity to such self-reflexive inner scrutiny. This scrutiny enacts a slowing down of perception, a sense of looking around and absorbing one’s place in the environment. Through an uncanny distortion, doubling back and becoming the environment. Vapourwave allows us to adopt both a blasé and a highly perceptive attitude to the ad-saturated world in which we exist; the metropolis of the internet becoming some great labyrinth in which we linger at every turn, mesmerised by the neon palms swaying in time to the untimely music, to cans of diet coke and the universal resonance of that bold tick logo. Everything surrounds and coagulates, connects.

This aesthetic dwelling is crucial for ecology because it forces a recognition of the world which we are and in which we live, a recognition that notices patterns of interconnectedness and coexistence. For Gregory Bateson (2016), aesthetics means ‘responsiveness to the pattern which connects. The pattern which connects is a meta-pattern’; both cities and their parts form part of this pattern, of the patterned aesthetic of vapourwave. The metropolis, the mall, the fountain plaza, the computer screen, the window of a building, the burnished, pixellated sunset. All are the environs of sound and vision, the movement between figure and ground, the deconstruction of synecdoche. The part and the whole are constantly supplementing each other (the song, the sample; the symbolism, the surface aesthetic). It’s a bewildering, shape-shifting experience. It forces us to take notice of our world. There’s something about vapourwave which always suggests to me a sort of endless highway, where the vehicles move as if through some viscous substance that drags the experience of time and space. Our perception becomes blurred and starry, with blips of unconsciousness and moments of epiphanic reverie. Things around us fade or glow. The radio rumbles in the darkest cavity of our chest. Am I even breathing? I don’t feel human. Is this freedom?

Alongside this dwelling is a certain playfulness of a way unique to vapourwave. James Ferraro’s Far Side Virtual (2011) might be the classic here. It blends together the inane and cornily flourishing samples from Muzak with automated audio speech stolen from corporate contexts and sound effects from everyday tech life—the message-send swoop, a mouse click, laptop crashing sounds and start-up tunes. The result is something that might reflect Jean-Francois Lyotard’s famous definition of postmodernism as ‘eclecticism’, the ‘degree zero of contemporary general culture [where] one listens to reggae, watches Westerns, eats MacDonald’s for lunch and local cuisine for dinner, wears Paris perfume in Tokyo and retro clothing in Hong Kong; knowledge is a matter for TV games’ (2004: 76). This eclecticism is made playfully manifest in Ferraro’s lively, atmospheric and at times downright trippy record, where twinkles of commercially-drenched, techy synths give way to stuttering keyboards, ringtone effects and twirls of familiar message noises which become maddeningly synced with finger clicks and conversations between robotic voices. A CONUNDRUM article argues that ‘since vapourwave functions namely as commentary, it loops, pitch-shifts and “screws” the utopia of the virtual plaza, creating a harsh, grating sound in away that brings each muzak sample’s faults to the forefront of the track’. This is certainly true of Ferraro, but I’d also suggest that vapourwave is more than mere commentary; Ferraro especially revels in the silliness of corporate culture (check out ‘Pixarnia and the Future of Norman Rockwell’, with its drink slurping sound effects and jingly, kids tv-worthy melody), at the same time as revealing its peculiar utopian unreality, a world of shimmering sound and holograms. There’s a self-consciously affective and pleasurable aspect to the music. Sometimes it sounds like the demonstration music on an art channel, to the point where I’m expecting some beautiful, sellotaped creation to materialise with every musical flourish.

On the other hand, there’s the total weirdness of ‘Palm Trees, Wi-Fi and Dream Sushi’, which takes us through a scintillatingly bizarre encounter with a ‘touchscreen waiter’ who explains the ordering process at a sushi restaurant—apparently in Times Square, with Gordon Ramsay as chef—to the backdrop of exuberant synths and glitchy effects which sound like a Windows 95 laptop gone haywire, or merely said customer making her selections from the menu software. The result is to render a future where restaurants and coffeehouses are devoid of human interaction, becoming impersonal encounters with creepily enthusiastic machine waiters (creepy not just because they’d put me out of a job). The contrast between this manic happiness, this constant focus on choice, with the maddening music is to create a deep sense of unease, to reveal the artifice of such utopian tech constructions. Do we really have a choice? Is life being boiled down to a series of computer menus? Is the future bound to the unsettling intonations of such robotic encounters? I can’t help but escape into the absurdity of the music and try to forget this hauntological disaster is always-already constantly happening…

The comparatively meditative ‘Bags’ weaves its entrancing ambience from an early Windows startup theme, dipping into sonorous caverns of sparkling synths and lifting for air bubbles and irregular, incongruous finger clicks. I am reminded here of a beautiful essay by Steven Connor on the magic of objects, specifically here bags: ‘because they are in essence such fleshly or bodily things, bags enact as nothing else does our sense of the relation between inside and outside. We are creatures who find it easy and pleasurable to imagine living on the inside of another body’. There’s an amniotic vibe to Ferarro’s ‘Bags’; the swaying, dreamy pace that makes us feel as though we are inside those palms, or encased within a glossy plastic number, bouncing away against some glamorous knee. Just as humans have a sort of supplementary, life-giving association with bags, we also have this relationship with the plazas of capitalism and the affective world they render. Ferarro has said that he conceived of Far Side Virtual as a series of ringtones, a musical form which inherently suggests consumer transience, tackiness, kitsch, the whims of passing fashions (not least because the polyphonic presets change with each phone upgrade). He’s also said that he loves the idea of the album being ‘performed b a Philharmonic Orchestra […] Imagining an orchestra given X-Box controllers instead of mallets, iPhones instead of violins, ring tones instead of Tubular bells, Starbucks cups instead of cymbals. All streamed online, viewable on a megascreen in Times Square’. That’s what’s special about vapourwave: its commitment to the endurance of art and the a e s t h e t i c alongside an ambiguous relationship with the ephemerality of corporate kitsch. The artistic rearrangement of these samples, alongside their visual presentation and marketing as alt music through sites like Bandcamp, completely reterritorialises their original framework of meaning.

There’s a sense in which this music—with its self-conscious materiality, the recognisably tacky mattering of its samples, its embrace of the ambient disruption of foreground and background—is inherently committed to some kind of hauntological ecological project, the kind advocated by Tim Morton’s dark ecological poetics. As Ferarro himself says of his album, it’s a ‘rubbery plastic symphony for global warming, dedicated to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch’. Vapourwave recycles culture, proliferates both beauty and trash, endlessly parodies itself and its references. It renders explicitly what Marc Augé calls the ‘non-places’ of supermodernity: the anonymous malls, airports, offices and stations where cultures blend and collide and become foreign places of blank existence, of non-place, of disembodied temporality and physical and social experience. Places emptied out of cultural specificity. Places where one might eat Japanese sushi in a New York airport restaurant, concocted by a holographic rendition of a grumpy English chef and served by a robot developed and programmed by a Chinese tech company. Vapourwave is melancholy and strangely displaced. The frequent use of anonymity by many of its prominent artists (Xavier, for example, is responsible for more than just Macintosh Plus), alongside the Eastern characters for song titles, creates again a dehumanised, uncanny and culturally displaced understanding of identity. It weaves an almost Orientalist mystery through its art, so that we can’t quite geographically place the origins and players of this musical movement. It’s all about dissemination, reappropriation, the instancy of recycled production; but it’s also about slowing down to notice the flaws inherent in our everyday, consumer lives. The heavily sampled, rhizomatic nature of vapourwave forces you to become a more active consumer of both music and other forms of material pleasure, from picking your morning coffee to choosing your desktop screensaver. Perhaps it’s this recognition that gives vapourwave the vague trace of disruptive impulse; the way it strips away the uneasy pleasures and pink mist of the late capitalist plaza and replaces it with a mystique that haunts us back from the future. Objects and humans withdraw from our grasp and we are left with the surface detritus of crushed coke cans, defunct MacBooks, coffee cups and robot voices stuck on repeat, cleaning the floor of the mall to a vicious gleam that threatens to bounce back like a screen and remind us that we haven’t left the room at all – we’re still on the internet, chasing our dreams.

Bibliography

Augé, Marc, 2009. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (London: Verso).

Bateson, Gregory, 2016. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Available at: http://www.oikos.org/mind&nature.htm. [Accessed 22.1.17].

Derrida, Jacques, 1994. Spectres of Marx. Extracts available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/derrida2.htm [Accessed 22.1.17].

Eno, Brian, 1978. ’Music for Airports liner notes’. Available at: http://music.hyperreal.org/artists/brian_eno/MFA-txt.html [Accessed 22.1.17].

Freud, Sigmund, 2003. The Uncanny, trans. by David McLintock, (London: Penguin).

Heidegger, Martin, 2008. Being and Time, trans. by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, (New York: Harper Perennial).

Jameson, Fredric, 1991. Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press).

Lyotard, Jean-Francois, 2004. Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Morton, Timothy, 2001. ‘“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” as an Ambient Poem; a Study of a Dialectical Image; with Some Remarks on Coleridge and Wordsworth’, https://www.rc.umd.edu/praxis/ecology/morton/morton.html

Morton, Timothy, 2002. ‘Why Ambient Poetics? Outline for a Depthless Ecology’, The Wordsworth Circle, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 52-56.

Morton, Timothy, 2016. Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (New York: Columbia University Press).

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques 2011. Reveries of the Solitary Walker, trans. by Russell Goulbourne, (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics).

Tanner, Grafton, 2016. Babbling Corpse: Vapourwave and the Commodification of Ghosts (Winchester: Zero Books).

Young, Jock, 2007. The Vertigo of Late Modernity (London: SAGE).