(in alphabetical order…)

Beach House, Depression Cherry

It’s moody and melancholy and perfect for Sunday afternoons in winter, where hardly an hour of light graces us with its presence. The singing is woozy and lush, the track titles are typical Beach House (‘Wildflower’, ‘Levitation’, ‘Days of Candy’) and a mellow, dissonant drone seems to drift over most of the songs. There’s a whispery feeling to the vocals and a scratchy-sounding organ keyboard. Also, the album is coated in soft red velvet, so the physical copy is pretty beautiful, and there’s definitely a ‘tactile’ sense to the music itself, with all the sparkling effects and the echoing texture of Legrand’s voice. I like Beach House for the same reason I like Cocteau Twins: the music enfolds you like the atoms (or pixels?) of another world – it doesn’t sound 100% human, there’s something too mystical about it. The band released a website with typed lyric sheets, which adds to the sense that the whole album is a hazy collection of dream poems. It was released in late summer but I have listened to it a lot more in winter; it’s like the sound of Victoria Legrand’s hazy, drifting vocals is better suited to the cold weather, the whiter light, the sheen of ice.

Favourite tracks: ‘Space Song’, ‘Levitation’, ‘PPP’.

Beirut, No, No, No

There were a few weeks where I sort of just played this album on repeat in the restaurant where I work. Generally it was pretty harshly reviewed and there is a sense that single tracks stand out more than the whole. Still, I appreciated that cheerful continental folk vibe to get me through the autumn and winter with its remnants of pastel-hazed summer. Even though the songwriting might not be as *original* or *inventive* as 2011’s The Rip Tide, you can have a lot of fun with some staccato beats and percussion. Plus I love a bit of brass.

Favourite tracks: ‘No, No, No’, ‘Gibraltar’, ‘Perth’.

Belle and Sebastian, Girls in Peacetime Want to Dance

Just the sort of lively pop weirdness you need to brighten your January, when the album was released. I love Belle and Sebastian, the way they create simple catchy folk-pop but base it around stories and characters and inventive lyrics about lost girls and ~cutely~ wayward indie kids. There’s a bit more experimentation than usual on this one: from the funky disco atmosphere of ‘The Party Line’ and ‘Perfect Couples’ to the epic near-7-minute dance track ‘Enter Sylvia Plath’, there’s something for everyone. ‘Nobody’s Empire’, which approaches the subject of lead singer Stuart Murdoch’s MS, reveals Murdoch’s general genius for lilting melodies punched through with a weightier-than-usual buildup and bass line. ‘Ever Had a Little Faith’ is maybe the closest song to old-school Belle & Sebastian. Generally this album is full of interesting licks and typically witty lyrics, and its experimentation lends well to repeated listening.

Favourite tracks: ‘Nobody’s Empire’, ‘The Party Line’, ‘Enter Sylvia Plath’.

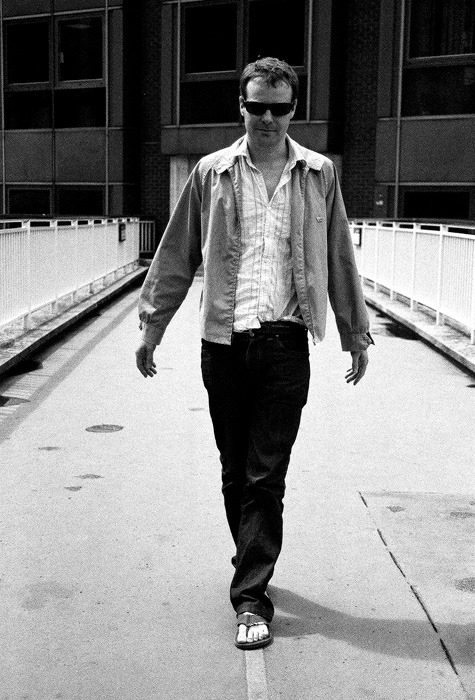

Blur, The Magic Whip

Blur’s first album since 2003, The Magic Whip is kind of a mystical, surreal experience. Along with the artwork (a neon ice cream and some Chinese lettering), the album’s whole vibe sort of reminds me of this weird game I used to have for Sega Megadrive where you could do fight scenes on top of an apartment roof in the depths of Tokyo. Everything was blurry and glitchy and full of bright lights against the backdrop of glittering darkness. The Magic Whip is set in Hong Kong rather than Tokyo, but it has that strange sense of futuristic metropolitan darkness. It takes away the grunginess of Blur and sonic spaciness of 13 and enters a more self-aware, perhaps even ‘postmodern’ (ugh, the implications of that term) territory.

Well, for one there’s the obvious cultural borrowing from Hong Kong, where the album came together; there’s also the sense of meta-britpop on songs like ‘Lonesome Street’ and ‘I Broadcast’ which update the whistle-along laddish bounce of 1990s culture for a more accelerated version of the jaded digital and cosmopolitan era (‘Lonesome Street’ is overlaid with the sound of someone reporting – on the news? – sparkling synths and echoing city street noises). The sense of absurdity and collapse, like in ‘I Broadcast’ where the chorus falls into the repeated line: I’m running being played over Graham Coxon’s sharp guitar. It’s a complex and intriguing album with some sweet bass lines and dreamy Damon Albarn vocals. Listening to it really does sort of take you somewhere else. Also, ‘Mirrorball’, the record’s final song, sounds almost like it belongs on a David Lynch soundtrack.

Favourite tracks: ‘Ghost Ship’, ‘Pyongyang’, ‘My Terracotta Heart’.

Clarence Clarity, No Now

From the glitchy, 90s Windows computer aesthetic of its videos to the vibrating bass, disco rhythms and shrieking guitars and falsetto vocals, this is one crazy good album. Not many folk are brave enough to put out 20 tracks on their debut album, but the effect of doing so sort of drags you underwater into a world of sound that’s electric as a field of lightning, as shrieking neon as that purple lava you get in Sonic the Hedgehog 2, Chemical Plant Zone. Sorry, is that mixed metaphors? Who cares, with music like this, everything is mixed to fuck.

Some of the songs have a cinematic feel, which is hard to define except for a sort of atmosphere created by all the glitchy sound effects and samples (listen to the start of ‘The Gospel Truth’, for example). It’s a relief when Clarity strips back into ‘purer’ or softer vocals (see ‘With No Fear’), but also a great feeling when the effects pedals step on again, like having water thrown over you. Cold, shocking, refreshing. Kinda like the whole album. You’ve got references to ‘worm holes’ and ‘cancer™ in the water’ and all sorts of surreal cyber imagery and staccato vocals in reverse (‘Tathagatagarbha’ is straight out of Twin Peaks’ Red Room, right?). ‘Those Who Can’t, Cheat’ is the kind of psycho disco death funk they would play at the end of the world. I was lucky enough to see Clarence supporting Jungle in Edinburgh this year and I can say that it all sounds sweet as hell live – the band’s energy really plays out the craziness of the album – which isn’t always always the case when the production is one of the best parts.

Favourite tracks: ‘Those Who Can’t, Cheat’, ‘Bloodbarf’, ‘Will to Believe’.

(Also, I think ‘Hit Factory of Sadness’ is one of my favourite song titles ever).

Foals, What Went Down

I guess the critical/commercial success of Foals’ fourth album (in October they were voted ‘Best Act in the World Today’ at the Q Awards) means I don’t need to say much to justify my choice. I’ve been with Foals ever since they were bouncing out math rock on early Skins, and this album was no letdown. For one, it has several tracks which follow in the footsteps of ‘Spanish Sahara’: ‘London Thunder’ is a beautiful, atmospheric track with a lovely build, and even Lana Del Rey has sung her praises for ‘Give It All’, which addresses love as a kind of fragile presence/absence, of digital melancholia – ‘Give me the way it could have been / Give me the ghost that’s on the screen’. ‘Birch Tree’ has that sort of upbeat, syncopated feel reminiscent of ‘My Number’ (from Holy Fire). Other than the softer tracks, it’s a whole lot rockier than previous albums, especially on the frenzied ‘What Went Down’ and jangly guitar rhythms of ‘Mountain at My Gates’. I listened to this all throughout the month it took to move from my old flat, so it will always have that sense of dislocation and haunting futurity for me… (plus the stress of shifting boxes and scrubbing kitchens).

Favourite tracks: ‘Mountain At My Gates’, ‘Birch Tree’, ‘London Thunder’.

Gaz Coombes, Matador

I have to confess that while Matador was released in April, I didn’t actually listen to this album until about a month ago, when I found out my cousin (the lovely Hannah Lou Clark) was supporting him on his UK tour dates. I saw Supergrass a long time ago when they supported Coldplay at Bellahouston Park, but I don’t remember much of it, especially as I was right at the back! This is such a gorgeous album though, I swear I’ve listened to ‘Matador’ on repeat to and from work for the last fortnight at least. It has great range and depth, another fine example of the maturity that can come out of the Britpop era. Coombes can sound both delicate and powerful, and there’s a certainty, a sureness, to this record. There are songs whose haunting atmosphere is complimented by stunning but simple lyrics (‘Worry fades the soul away / I’ll take the hurricane for you’ – ’20/20’) and climactic choruses. If I close my eyes I imagine this song being played over a dramatic film scene, like someone running through city streets, a breakdown, things exploding, changing. Something like that. I know it’s cheesy but there are definitely songs on this album which you could call sublime in the true sense of the word. Disorientating, awesome, majestic, powerful. Gospel influences, electronic beats, acoustic guitar. I’m still in love with it.

Favourite tracks (this was difficult, and may change): ‘The Girl Who Fell to Earth’, ‘Matador’, ’20/20’.

Kurt Vile, B’lieve I’m Going Down

Aw man, there’s just this beautiful twang to Kurt Vile’s music that is so addictive. It’s not just his hair. The country twang of guitars, his sweetly droning, idiosyncratic voice. You can see the influence of Nick Drake, maybe a touch of Dylan, but also a very modern sense of disconnectedness, of goofiness even – the sense of being very self-aware but at the same time alienated from who that self is. Some of the songs sound a bit ballad-like, but there’s always a kind of dissonant, bluesy twist. He really nails his lyrics and imagery too: ‘I hang glide into the valley of ashes’, ‘A headache like a ShopVac coughing dust bunnies’. The twinge and stuffed wordiness of ‘Pretty Pimpin’ proves strangely addictive, as does that developing, repeating, turning, twanging guitar riff. ‘That’s Life, tho (almost hate to say)’ is a darker, sadder sort of folk ballad. Generally, it’s an album to listen to dreamily, maybe on a car journey, but also one that goes well in the background of bars, because it’s lively enough, and pretty damn cool.

Favourite tracks: ‘Pretty Pimpin’, ‘That’s life tho (almost hate to say)’, ‘I’m an Outlaw’.

Lana Del Rey, Honeymoon

I could rave about Lana all day. She has the genius of Lady Gaga, Bowie and Madonna in her creation of the ‘gangster Nancy Sinatra’ persona, but an old-school Hollywood voice that haunts and croons and glides over dark, sweet melodies. Honeymoon is very much a coherent piece of art. It’s a very visual album, much in the tradition of Del Rey’s previous work (the monochrome vibe of Ultraviolence played out in the gloomy, stripped back energy of the Dan Auerbach produced songs). Picture a summer-hazed beach with pastel huts and neon-signed strip clubs, peeling paint. Lana writhing about in her mint green muslin in the video for ‘High By the Beach’. It’s her dark paradise, a retro realm of sweet pop richly infused with jazz, blues, R&B, trap, disco and poetry. The loveliest recital of T. S. Eliot’s ‘Burnt Norton’ I’ve ever heard, soft and haunting. A Nina Simone cover. Tracks like ‘Salvatore’ and ‘Terrence Loves You’ really demonstrate the crystal clarity of her voice, as well as the strength of her range. The title track can be described in many ways, but I prefer the terms glimmering and cinematic. Really, it was the perfect soundtrack for a melancholy, post-graduation summer — except I swapped the retro cars and ice cream for long walks in Glasgow rain.

Favourite songs (again, so hard): ‘Terrence Loves You’, ‘Honeymoon’, ‘The Blackest Day’.

Laura Marling, Short Movie

It’s quite lovely to witness Laura Marling’s music maturity. From the honest folk pop of Alas I Cannot Swim to the stronger, mythological tones of Once I Was an Eagle, she has really developed and expanded her sound, not just in a literal sense but in a metaphysical one too. Does that make sense? I mean the way that her music opens worlds up. Eerie, dark soundscapes and cessations of space, interruptions and pauses and softly twangling guitars. Opening track ‘Warrior’ is spellbinding, allusive and elusive; full of echoes and misty vocals, guitar licks that curl round and round. It feels distinctively American, as opposed to, for example, the Englishness, countryside sweetness of I Speak Because I Can. There’s a sense of being lost, looking for something (‘the warrior I’ve been looking for’), of endlessly journeying.

For most of the record Marling steps away from the acoustic songwriting (delicate, but sometimes forceful) which won her fame in earlier records; her electric guitar simmers through the tracks, building around her increasingly impassioned vocals. On ‘False Hope’, a track about Hurricane Sandy, she steals us away from the vague landscapes of ‘Warrior’ to the metropolis, the Upper West Side, where darkness falls and electricity fails as she tells us of the storm. The weather plays pathetic fallacy to the storminess of the singer’s mind: ‘Is it still okay that I don’t know how to be at all? / There’s a party uptown but I just don’t feel like I belong at all / Do I?’. ‘False Hope’ slides into a more traditional Marling track, ‘I Feel Your Love’, which rolls along like a nice old folk song, a bit Staves-like maybe, but more haunting. Her more ‘spoken’ delivery of vocals, intertwined with some searingly brief high notes, in ‘Strange’ for example, bring to mind Joni Mitchell. At times she addresses different characters: spurned lovers, young girls who mirror herself, the ‘woman downstairs’ who’s lost her mind. The overall effect is less introspective, and more fleeting, transient: the self behind the voice slips in and out of view, through various narratives and images. There’s a restlessness which contributes to the Americana vibe, but one which is perhaps also simply the natural expression of a successful singer songwriter still only 25, trying to find her way in the world…

Favourite tracks: ‘Warrior’, ‘False Hope’, ‘Worship Me’.

Little Comets, Hope is Just a State of Mind

My favourite band for kitchen sink indie…I like how Little Comets ease you into their changes in sound through various EPs released throughout the year. With the tingly guitars released on ‘Salt’ and the earnest lyrics, a ballad (‘The Assisted’) and emphatic drumming (‘Ex-Cathedra’) of ‘The Sanguine EP’, listeners were prepared for what was to come on Hope is Just a State of Mind, which seems to head towards what might be called a more eccentrically pop direction. One of my favourite things about this band is how they delve into the political and there’s certainly no avoiding it on this album, from the dig at Robin Thicke’s gender politics in ‘The Blur, the Line, and the Thickest of Onions’ to the lethargy of rock and roll in ‘Formula’ and the cultural demonisation of single motherhood in ‘The Daily Grind’: ‘You must feel so proud / Stigmatising every single mother / While your own world’s falling down’. Songs like ‘The Gift of Sound’ and ‘Formula’ have a more straightforward energetic pop vibe, whereas ‘B&B’ begins with an accapella moment and revolves around the repeated line: ‘my own mother cannot take me back’. There’s lots of thudding drumming and a swinging sort of emphatic, repetitive melody. The song, incidentally, is about bedroom tax and Robert Coles has eloquently said of the lyrics:

‘Lyrically the words came quite quickly as I always had the “even my own mother cannot take me back” line in my head from writing the melody. I knew it was going to be about politics: specifically the patronisation of people by the political class in both ideology and delivery, and the way that my own region has been altered by the blue hoards of conservatism.

The title stems from a tweet by Grant Shapps regarding the last budget – “budget 2014 cuts bingo & beer tax helping hardworking people do more of the things they enjoy. RT to spread the word”. Beer and Bingo – because there’s nothing else to do.

I think the first verse is just frustration with the attitude put across by politicians that suggests that they think people are total idiots – policies light on detail, simplistic ideology, framing debates in headlines, constant ill behaviour. Plus from the other end of the scale the total demonisation of the less well off in the swingeing benefit cuts typified by the bedroom tax. I just think it is bizarre and to treat us with this brazen amount of contempt.

It really got me thinking about the north east getting so bashed up in the time of Thatcher – destroying lives and communities because of a need to dominate on an ideological level. I think the second verse tries to convey the depressing notion that beyond this pain, she also eradicated trades and skillsets that had been built for hundreds of years without the prospect of anything new, or transferability. To extinguish a trade, a way of life…. Wow….. That’s a pretty crazy course of action.

It’s almost like she stole those years from us – and it feels a little like it is being echoed now. Taking away what someone relies on is oppression, and this is being felt in communities across our country today – horrified in the knowledge that it will continue until people are so battered that they accept it. The worst part is if you look closely enough, past Grant’s apparent carrot you can see the joy in the eyes behind the ghastly stick, and they look frighteningly familiar” (Source: Little Comets’ Lyric Blog).

I guess I’ve included the quote because I think the politics have become more direct in this album and it’s interesting to flesh out the backstory here. Sure, there have been plenty of ‘northern’ bands before, but rarely have I listened to a pop or indie band who engage with their politics so directly and so articulately (usually this space is reserved for punk or rock – Manic Street Preachers of course, representing a ‘marginalised’ Welsh perspective). Aside from lyrical content, you’ve got the usual pleasures of Little Comets harmonies, shredding guitar licks and bouncy rhythms. ‘My Boy William’ is wonderful live, the way it builds up and everyone following the drum rhythm. ‘Little Italy’ is great fun too, with its cascading melodies (liiiittalll iiiitaaalllyyyyy I reeAAd heeEre) and syncopated rhythm. It’s true, on this album (especially on ‘Salt’), the songs are very up and down, rarely straightforward and often lines are lyrically and melodically convoluted; this isn’t a criticism but more a reflection of what seems to be a desire to push the formulaic boundaries of pop, to infuse guitar chords with lush vocal harmonies and ringing percussion. To represent detailed, difficult subjects in pop is never going to be easy, but Little Comets nail it in their own unique, beautiful way. Look forward to seeing them again live next year!

Favourite tracks: ‘Don’t Fool Yourself’, ‘Little Italy’, ‘The Blur, the Line & the Thickest of Onions’.

The Maccabees, Marks to Prove It

Well, to be honest I never would’ve thought I’d be including The Maccabees on my 2015 albums of the year. Over the last few years, I haven’t spared much thought for the band other than as another soundtrack to the general indie trend of the last ten years: a band mentioned frequently in NME perhaps, soundtracking lovelorn scenes in movies, but nothing particularly distinct other than in their creation of twee indie pop. However, one night after work I was lying on the floor recovering from a terrible shift with the radio on, listening to X-Posure With John Kennedy on what used to be XFM. The Maccabees were talking through their new album and playing the songs, and I was pleasantly surprised by how intriguing the sound was, as well as how articulate the band were in talking through the writing process and the stories behind the songs. I guess the next day I went out and bought the album. It definitely sounds a long way away from ‘Toothpaste Kisses’, though the added kazoos and varied percussion doesn’t spoil the simple joy of good plain songwriting. The songs have a weight to them, a grander atmosphere, especially the weird dissonance on the likes of ‘River Song’. ‘Silence’, however, is quietly beautiful, drifting along soft piano notes, subdued vocals and a somewhat eerie sample of an answering machine voice.

Where once you would recommend The Maccabees mostly to fans of The Mystery Jets, Pigeon Detectives or Futureheads, this album feels much more grownup, darker somehow, wilder and expansive. The lyrics vary in subject from the gentrification of London’s Elephant & Castle (the band’s hometown) to heartbreak (‘When you’re scared and lost / Don’t let it all build up’) and well, happiness (‘Something Like Happiness’). It’s refreshing to have a song that does just feel like at times like a gentle old ode to joy: ‘If you love them / Go and tell them’. ‘Marks to Prove It’, the opening track, feels confident and bouncy, with a sharp riff and assured vocals. It would fit in with a fast pop set from The Futureheads, but the rallying battle cry that precedes Orlando Weeks’ voice announces something slightly stranger, a record with new edge.

Favourite tracks: ‘Silence’, ‘River Song’, ‘Something Like Happiness’.

Tame Impala, Currents

I was introduced to Tame Impala mostly from one of the chefs at work playing it in the kitchen on Sunday mornings, and weirdly enough his psychedelic brand of synth pop seems appropriate preparation for a day serving Sunday roasts to hungover customers. It’s the swelling bass and brilliant synths that really catch you, the smooth falsetto and tingling production. You can tell Kevin Parker is a dream at studio magic, with flawless instrumental arrangement that makes for a sound that could be big or chilled, depending on how you play it. There’s some dark keyboard drama, there’s a lovelorn anthem (‘Eventually’) and what might tenuously be described as weird disco funk. For some reason (maybe all the synths, gossamer vocals and vintage-sounding guitars?) has a ‘bedroom-made’ feeling, but with a much slicker production than the DIY element might suggest. Some songs sound like they belong on a long, atmospheric train journey across a space desert; others sound like they’d fit on the cuts of drama interspersing a video game. There’s a dreaminess to songs like ‘Yes I’m Changing’, but a more radio-friendly funkiness to the likes of ‘The Less I Know the Better’, or even ‘Love/Paranoia’, with its silky beats and finger clicks. As the album progresses, the theme of heartbreak starts to really solidify and I guess that’s the overriding drive of the songs – a heartbreak that slows and stifles, morphs between introspection and the temptation of mild bombast.

Favourite tracks: ‘Yes I’m Changing’, ‘The Less I Know the Better’, ‘Love/Paranoia’.

Stornoway, Bonxie

This was a lovely album to enjoy in spring, from the hopeful folksiness to the cute origami bird on the cover. I guess it got me through that period of hell in my life that was finals. I would go on walks around Kelvindale where all the cherry blossoms were, listening to the soft acoustic licks and all the soothing bird sound effects. It’s an album to enjoy by the sea perhaps, full of a sort of longing. There’s the noise of distant foghorns, the rolling harp-like guitar and sparkling xylophone over the drifting shimmer of a wave-like cymbal. This is probably my favourite Stornaway album, or at least equal to the debut, Beachcomber’s Windowsill because of its more folksy atmosphere, its immersion in nature — the sense of being lost, deliciously lost by the edge of the ocean. ‘The Road You Didn’t Take’ especially boasts a shanty-like chorus which adds to the nautical theme and sort of swells up like you’re caught at sea, singing along irrevocably. Melodies build up to climaxes and fall back down into subdued, slower choruses, as if the speaker tries to articulate something about his surroundings (the beautiful environment) but fails to express them entirely. Sweet, comforting guitar licks glide us through (e.g., the start of ‘Sing With Our Senses’). Vocals are never aggressive, only sometimes shrill and generally soothing – like a bird’s? Apparently over 20 types of bird donated their song to the album, and let’s not forget that singer Brian Briggs is a Dr. of Ornithology! It’s just a lovely escapist sort of album, reminding you of seaside holidays from years ago, that childlike ability to sink into your surroundings and find wonder in a leaf, a taste of salt air, a bird call.

Favourite tracks: ‘The Road You Didn’t Take’, ‘We Were Giants’, ‘Between the Saltmarsh and the Sea’.

Swim Deep, Mothers

It seems everyone has been describing this album as Swim Deep’s foray into psych-pop. You only have to take a glance at the warping colour bleed of the cover art to pick up those vibes. The honey sweet guitar pop of Where the Heaven Are We has morphed into something heavier, more saturated. There are so many influences, but I suppose you could start with psychedelic music, house and kraut rock. Lots of bursting, colourful synths. It reminds me of The Horrors’ Primary Colours, not only because it’s a ‘change-around’ album, but also the subdued, atmospheric reworking of prior image and musical style. Songs like ‘Honey’ and ‘The Sea’ from their debut album were chilled and loose with catchy melodies, and while Mothers retains the catchy melodies, its style has tightened up a bit. The instrumental elements are more complex; songs open up a multilayered world rather than the silver stream of a simple pop tune. ‘To My Brother’ has an epic quality, building up to the chorus with some extravagance – weirdly, the sort of mistiness of the vocals and quirky synths remind me of Seal. I’m not sure why, or whether that’s even an accurate comparison, but the link just popped into my head. I love the way critics have compared ‘Namaste’ to discordant game show music, which obviously fits in with the 1990s vibes of the video. All that beige, those glasses, the sense of mania reflected in the music! It’s more mature maybe, but still fun.

Favourite tracks: ‘To My Brother’, ‘Namaste’, ‘Imagination’.

A few others…

- Beach House, Thank Your Lucky Stars (two albums in one year, ‘nuff said)

- Florence & the Machine, How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful

- The Libertines, Anthems for Doomed Youth (listening to it to drag up the old nostalgia of discovering the first albums, for the lovely production and Doherty vocals on ‘You’re My Waterloo’ and Carl Barat’s very English swagger).

- Prides, The Way Back Up (Stewart Brock has come a fair way since Drive-By Argument (big up a band from Ayr!) but the wide, electronic sound of Prides has its heart in the original synthiness of Drive-By Argument which developed into more distinctly electronic side-project, Midnight Lion. Obvious comparisons are to Chvrches, but maybe also a bit of Daft Punk. Radio-friendly but I’d imagine really big and energetic live, plus whenever I hear them I get sweet teenage nostalgia for Drive-By Argument).

- Sufjan Stevens, Carrie & Lowell

- Years & Years, Communion (sparkly EDM pop with plenty of pluck, from a band whose singer starred in Skins and Stuart Murdoch’s indie flick, God Help the Girl).