~ https://thelongocean.bandcamp.com/album/the-long-ocean ~

There is a struggle, the suspension of hoar frost crusts time itself as it trickles over the sea. At first light we watch for an opening. Even in attics and city bedsits, the sea remains in our blood. We feel it cold as ice at the illness times: how darkly we sink into the sheets, hoping the pain in our skins will dissolve back to lucent matter, the night wisps of somebody else’s aura.

A voice enters soft and lo-fi, filling the interludes that swirl around haunted piano arpeggios, the silver streaks that spill on the ocean’s tides. I am afloat in muted clicks that keep me close to the surface, where the sound echoes in drips, as in a swimming pool. I listen for his voice as it mists the glass of the window. I inhabit that glass in the silence, waiting for some melody to sparkle with any dissonance sufficient to crack my crystal prison. Percussion is slightly hard, a clack, clacking. Crackle. Predictive appearance, seductive. “I’m under your spell / and I’m under under”. Subaquatic passion, staring at the world from beneath, behind, the film of its surface. See how everything shimmers. It’s quantum physics. You can’t peel off the surface of reality, its candy sprinkles, its gilt, to see what darkness and delight lies beneath; you’re already deep under, withdrawing, closing.

There’s the haunted aesthetic we find in Burial. Something more organic, elusive; the rural alternative to Burial’s empty midnight metropolis. On ‘Raindrops’ the muted sound of gulls weaves in and out of a DJ Shadow, Entroducing…..-era riff and the shimmering playful jazz of a brighter piano, a celeste of some sort…the sound of wind chimes through the minuscule ears of insects, so very high-pitched, so very sweet. You can imagine the tinkle of glass as you toast your favourite jellyfish, spirit animal that sucks its seven temporalities tentacular around it, moving them in sweeping undulations that rupture the cyclical moon-time of the waves. You open your flesh to the ocean, every salt crystal forming a bead in your pores. Desire is the fulfilling of absent substance, the spacing of the gap between lack and attainment. The passage of sailing, not knowing what darkness, what deep blue, you are setting off into, heart curved sharp by the cut of a crescent moon.

If Burial is, as Mark Fisher puts it, ‘London after the rave’, The Long Ocean is the abandoned nightclub pavilion, the sea’s dull roar mingling with those shadowy echoes of ecstasy. The slowed-down groans of a former generation’s momentary joy. Angels caught in the sand of an hour glass, being tipped, a largo mode of clock-ticking, grains of time slipping endlessly over the rasp of voices. I set this album to cassette tape, allowing the crackles to augment and mingle. I could be in the murmuring belly of a ship, hearing the rasps of a radio mix with this transcendent, nowhere music. It’s the sound of twilight set to reflections of quartz made bright momentarily by deepwater bioluminescence. What is that whine, that eerie peal? The sound of lost dolphins, the painful song of a lonesome whale? The whale is a heart’s darkness, a shadow-side of waking reality. You can lose yourself inside it, feel dreams close over you, prised from the wax, the oil-black skin.

Four Tet at his most otherworldly. Hypnotic loops, the soft distortion, the natural ambience. I am walking down an abandoned street, where weird green plants sprawl through the smashed-in windows of Brutalist buildings. Night birds chirp the tart remnants of forgotten songs. I am hooked on the wave-like rhythmic pulse of his words. My footsteps echo, down the street, down the passage, down the shallows to the deep where tarmac melts into oil-black sea.

There’s a sense of dark, spreading space, interpenetrated by twinkling scintillations; not unlike the plaza-like ambience of mallsoft and certain variations of vapourwave. Think: diamonds in the tarry pavement, stars reflected on the ebony surface of the midnight sea. A more crystalline James Ferraro, Marble Surf; The Long Ocean swaps those choir-like, ice-cream van speaker crackles for a more precise intricacy of lattice parameters, cross-rhythms of tinkling percussion and soaring, yet always subtle, beats. Think also of something like GOLDEN LIVING ROOM’s New Nostalgia, its eerie shimmers of late night lo-fi mixed with the bright sound files of near-future cyberspace, everything sounding slightly subterranean, that tinniness of dissonance. On The Long Ocean, however, instead of the glitch effects of hardware, the sounds chosen here are derived from natural materials and technics. The hollow click of driftwood, billows of cooling wind, cave-like echoes, the clinking of a necklace of shells with every percussive sprinkle (‘The Crest’). There’s a collector’s sense of amassed trinkets, effortlessly slinking along intricately simple bass-lines, hardened by industrial beats which burn in the weird space between background and foreground. What this music shares with vapourwave is a sense of slow, careful build towards the internal coherence of a detailed and evocative theme. The sadness and the beauty leaves its ghost stains on your brain, tugs at the blood which is full of the sea, makes you want to walk forever, or forever dream—rhythmic, contorted, returning serene.

Some of these tracks are totally devourable jams, the minimal intrusion of sampling giving way to those lusciously percussive beats, twists of lo-fi brass, crooning sexily over the building peal of mysterious beats (‘Gold Dust’). I’m reminded of a video game casino, an interlude space suspended in a three-dimensional, virtual world, where the colours and lights are all for our ersatz pleasure. On an island over an ocean we are sharing expensive littoral whiskies, toasting the way our skin glitters in its vitrics. Soon every vein will resurface, a curious craquelure marking time on the skin. Here we are, vacant, absent, deliciously distant.

Sometimes a roar of white noise, of wind rushing through a tunnel, subtly infiltrates a track (see the end of ‘The Crest’), reminding us that the space we’re inhabiting here is adorned by darkness and distance, is always deferring from itself. There’s definitely that Boards of Canada minimalism, the seamless weaving of samples in a way that seems hazy, reflective, a little haunted. A childlike naivety, a curious innocence; shadowed by the weight of a trembling void.

But there’s also a certain romance, even magic, to this record that I can’t quite pin to anything else. Not in the same way. Maybe it’s something to do with the celestial resonance of much of the track names, from ‘Star Light’ to ‘Gold Dust’ to closing beauty, ‘Stella Maris’. Latin for Star of the Sea, ‘Stella Maris’ is the feminine spirit, a protector who guides the soul at sea. This song is the album’s North Star, guiding us back through the waft and heft of its silvery, elusive currents. It sounds somehow out of time, built around the melancholy minimalism of a piano, sustaining its slow and careful path over the abyss of crackle, the tremors of the underworld, the ocean’s darkest depths. In the ‘Desecration Phrasebook’, a glossary collecting Anthropocene-related words, there’s a word, ‘shadow-time’, for ‘the sense of living in two or more orders of temporal scale simultaneously, an acknowledgement of the multiple out-of-jointnesses provoked by Anthropocene awareness’ (The Bureau of Linguistical Reality). We have to accept we are already living in the end of the world; it’s just that our sense of its time-scale is far beyond human comprehension. The fluid, amniotic ambience of ‘Stella Maris’, coupled with its fin-de-siecle, 1990s-style exploratory piano (think: Aphex Twin, DJ Shadow), creates this haunted sense of dual temporality, of always being on the cusp of something to-come at the same time as being homesick, nostalgic for a dreamland that came before but perhaps never was at all.

There’s something in the way this album romanticises the sea that suggests Glenn Albrecht’s word solastalgia: a form of existential distress caused by environmental change, global warming being the obvious example, as well as coastal erosion and the weather manifestations of climate change. Solastalgia derives from both ‘nostalgia’ and ‘solace’. Whereas nostalgia denotes a feeling of homesickness for a place and time we are no longer present in, solastalgia evokes that sense of distress caused by our home changing as we inhabit it, the affective impact of huge global shifts upon our individual, local experiences of landscape. The Long Ocean doesn’t leave us washed up at the end of the world, but suspended in the glittery salvation of its dark and strange and shimmering beauties. We come close to the weird and the terrifying, the dissonant samples of unrecognisable times, of creatures whose tremors rise up from the deep. Think of the pleasure and slight terror of binaural beats, the sublime understanding of our human insignificance as we gaze at the stars.

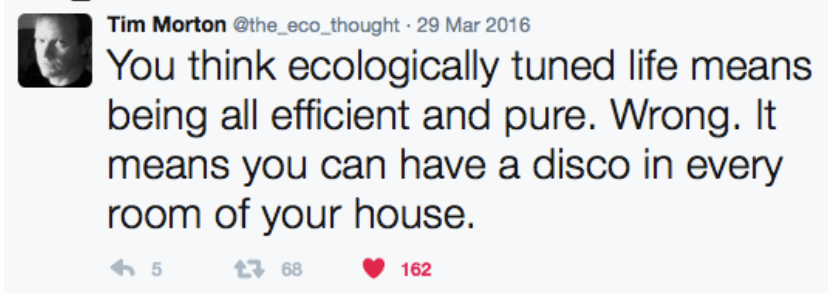

The beauty of an ecological thought is that it doesn’t have to be clogged with guilt, it can create something even lovelier before in its collective, technological and temporal possibilities. What would happen if you filled every room with solar panels, invited the creatures in, suspended your desire forever in those flickering, dancing refractions of light and sound and colour and life?