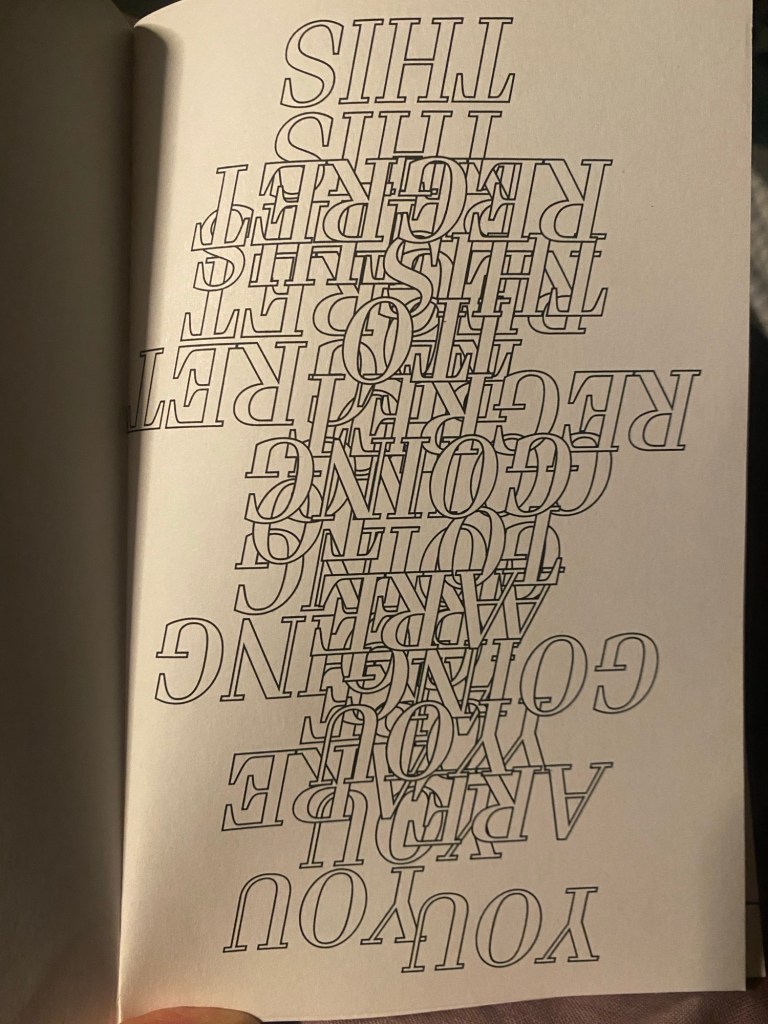

Tonight was the book launch for Tom Byam Shaw’s new short story collection, You Are Going to Regret This. Despite Storm Amy, Mount Florida Books was packed which is always so good to see (stay tuned as we’ll hopefully have another SPAM launch there before the year is out!). Tom read some pieces from the book — extracts from ‘Retail’ and ‘Arcana’. In conversation with Ian Macartney they talked about the New Weird, monstrosities and cannibalism as metaphors for capitalism, the world falling apart while people shop, continuity vs cataclysm, hauntology, real stories, Aberdeen, Glasgow, the Anderston motorway underpass (also a soft spot for me though I’m also partial to the Cowcaddens). They talked about a time when the Aberdeen open mic scene was so saturated there would be like seven different nights to choose from and regular performers would become minor local celebs. The shaping of each others’ work (both were members of the Re-Analogue art collective). At one point the word nice was said in a spiralling, elliptical comic-sweet way — I think they were reflecting on earlier days of friendship — and Katia was like this is nice ! bringing us into the present, that’s the point. The book looks great and sincere corkscrew really pulled a good number on the design. It will probably lure you into the basement which will smell of brand new trainers and you will have to confront something terrible. Everyone kept saying ‘for fans of Alison Rumfitt’. Yeah!

Afterwards we bandied out to The Ivory Hotel and with key questions bundled from some poetic eavesdropping of K’s café memories, I made people talk about the what and why of poetry, lifting these questions wholesale from said memories. Maybe having ‘a night off’ from poetry put me in this mood. Thanks to all who contributed. Everything was Guinness-flavoured and first thought.

J., Z. and K. shared their childhood guinea pig stories and we swapped anecdotes of encounters with rats (at home and in the workplace). The sorrow of a tiny animal curled around the absence of another.

Now the wind howls at the window.