To the best of my memory, I have only ever been on a sailing boat once. Or, I have only been happily in control of a sailing boat once (there was a time we had to try windsurfing in primary school, a time whose details have, thankfully, long been repressed). It was 2005, I was twelve years old, and had won a competition through the local youth club to go on a sailing trip to Oban. I don’t remember anything about what I must’ve learned regarding sailing, but I do recall a beautiful suite of seafaring terms: a special vocabulary which transformed previously mundane structural features into curious artefacts of mysterious potential: cleat, keel, stem, rudder, transform, tiller, clew, boom, shroud, telltale, jib, winch, deck and spreader. The man in charge was a hardened fisherman type; I don’t recall his name, but we called him the skipper. He was dismayed to learn I was a vegetarian, having packed little in the way of vegetables for our journey. I was happy to live off Ovaltine, jam rolls and digestives for the following days. It was such an odd combination of children—were we still children?—on that trip. No popular kids, but a few of the scarier misbehaviours (probably not okay to still call them neds), the freaks and geeks—then me, wherever I fit in. ‘Goth’, which in the case of my school was generally singular. Somehow, we all bonded rather than fought in the tiny space of that boat.

One boy, who would always be in fights, bullying and hunking his weight around, was so sweet to me. He saw I had eaten barely anything and gave me a whole bar of Cadbury Mint Chocolate, insisting I had all of it. It was such a kind gesture that I remember it still. Everyone was different at sea: softer, more honest. We were willing to admit our social vulnerabilities; there was no-one, no context, to perform for. A boy I’ll call L. opened up to me about his love for 2Pac, and when Coldplay came on the skipper’s stereo (it was their first truly mehhhh album, X&Y), we shared a little rant about how cheesy it was. We ate fruit out of tins, pulled scarves over our faces on deck and watched the coloured houses of Tobermory loom closer. The skipper let us all have a go at the tiller; he told us stories from previous trips, about how the weather had turned nasty and they’d had to pull themselves through miniature hurricanes. I found myself craving the wild mad weather, even as I was shivering in some inadequate waterproof jacket (I have a history of coming ill prepared to such outings). The skipper and I sort of oddly bonded, since I was usually the first one up in the group. He’d put the kettle on and we’d go out on deck to watch the sky. He’d point out things to look for in the cloud patterns, the colours that bloomed on the horizon. It’s this kind of practical knowledge that I thirst for. Chefs talking to me about how to sharpen knives, bake brownies; motorcyclists betraying the secrets to keeping your speed; engineers talking about formulas and team rivalries and how to build a bike wheel. I’m completely incapable of almost anything practical, so it’s always a magic alchemy to me. When people ask what I want to be when I grow up, I say shepherdess, even though I have little idea of what that entails, beyond reading the excellent The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks and occasionally listening to The Archers. I think I’d just be content to wander around hills.

Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight…

I awake to steady rainfall, first day of November. I have been thinking a lot about that sailing trip recently, mostly because I’ve been doing writing workshops in Greenock, and the nature of the place as a harbour town has everyone often turning back to boats and fishing topics. I talk to a chef at work about fishing, not because I’m all that interested in fish but because there’s something about its psychology that reminds me of times gone by. Once, I took myself out to Cardross on the train, following the road up to Ardmore to sit on the point which was a good spot for anglers. It was so quiet and still, the beaches strewn with lumps of quartz. I sat there for an hour or so, listening to the steady lap of the estuary, then slowly made my way home, tearing my skin on all the brambles. It had the feeling of a secret, overgrown place. A little out the way, a nest you could curl into: an almost island. I recall those tiny islands on the Swan Pond at Culzean Castle, where we used to leap across to. As a kid, I’d hide among the bamboos and rushes and feel entirely in my own little world. The pathways and grasses were lit with secret creatures, this 12th World I’d created—it was over a decade prior to Pokemon Go, but here I was in my augmented reality. I’d sit up on the top of the stairs reading for as late as possible, imagining that I was on top of a waterfall, and all before me was water cascading instead of carpet. I’d lie upside down and the ceiling became the first planes of a new universe. I’d wake up early and write it all down; but those pages are lost to whatever antique sale of the past stole my youth.

Now I am adult, less governed by diurnal rhythms. I find myself lost in the long bleed of night into day, up far too late in the bewildering recesses of the ocean online, the oceanic internet. Far corners where articles smudge their HEX numbers in true form down the page and I am rubbing my eyes to see beyond light. Time, perhaps, to rehash that old metaphor, surfing the web. Occasionally, some page would bring me crashing back down in the shallows; I’d wake up, ten minutes later, groggy on my keyboard. Press the refresh key. Instagram has me crossing continents at bewildering speed, lost in Moroccan markets, Mauritian beaches and Mexico City. In the depths of some nightclub then the heights of a Highland peak. So many fucking faces. Closeups of homemade cakes, delicious whisky. Memories. Oscillations I can hardly breathe in, watching my thumb make its onward scroll without my direction. The rhythms become flow, become repetition. I need an anchor. It’s been hours and hours and maybe I’m hungry.

On the boat, whose name I have sadly lost, we slept by gender in two separate cabin rooms. They were tiny, low-ceilinged, and we were just a handful of slugs pressed tight in our sleeping bags. It was better than a sleepover, because there was no pressure to stay up all night and we were all too exhausted from the sea air to talk much. I’d close my eyes and feel the steady rock of the boat’s hull as it bobbed on the water. There was a deep throb of something hitting against the walls outside, maybe a buoy or rope; it felt like a heartbeat. Sleeping in many strange places, the floors of friends’ flats and houses, in tents and on trains, I try to revisit that snug tight room where sleep was difficult to separate from consciousness itself. It was all of a darkness. Something Gaston Bachelard says in The Poetics of Space: ‘We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images.’ There was no mirror in that boat, so all I remember are smells and objects. No sign of my own pale and windswept face. Everything we ate was an old-fashioned brand; it made me think of rationing and traditional values. I wasn’t quite sure what that even meant.

I need an anchor. A place to dock in.

Governed by some primordial instinct, I go to make my dinner around the same time most nights—which happens to be one in the morning. The shipping forecast used to be the last thing on the radio, before a sea of white noise till dawn. When cutting veg, my fingers weak from another long day, I switch on the radio and there are the familiar intonations. I listen as I would a poem or a shopping list, a beautiful litany of place names, nouns, directives. I have no idea what any of it signifies. It’s been a double shift, perhaps, or an extreme stint in the library, a walk across the city. My mind is full of words and sounds, so many conversations. The debris of the day threatens to spill out as a siren’s cry, and how easily I could slump against the kitchen cupboards, wilt upon the floor. Make myself nothing but driftwood, no good turning till morning. But instead I chop veg, listen to the shipping forecast. It’s difficult to think you deserve food, even when your body’s burning for it and you haven’t eaten for hours. But there are so many other things to read or do! You need an anchor, a reason.

The general synopsis at midnight.

Many of my childhood lost afternoons, bleeding to evenings, were spent playing The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker on a GameCube I shared with my brother—avoiding the narrative quests and dungeons in favour of epic ventures across that cobalt ocean. What I wanted was that rousing sense of the wind’s spirit, the freedom to glide and find new islands. Whirlpools, tornados and Chtlulu-like creatures hurled me out to stranger lands. It was all so beautifully rendered, an expansive thalassic field of possibility; with each route I was fashioning some lovelorn story for my lonely hero. The ocean has always represented for me some point of erasure where reality dissolves into imagination. I think maybe it’s this perceptive meshing that we need to attune to in order to make sense of the vast scale effects of the Anthropocene. How else to grasp those resonant shockwaves of consequence, whose manifestations often transcend our human grasp of time and space?

Headache, Viking, southwesterly veering. The same refrain, moderate or good. When occasionally poor at times, do I picture the sailors with rain lashing their faces, rising through mist towards mainland? Is that even where they want to head? Rain at times, smooth or slight, variable 3 or 4. The dwelling conditionals; always between, never quite certain. The weather being this immense, elusive flux you can guess at, the way paint might guess at true colour. Cyclonic 4 or 5. In Fitzroy are there storms circling around the bay? Very few of these places could I point to on a map. I like the ambiguity, the fact of their being out there, starring the banks and shores and isles of Britain and beyond: Shannon, Fastnet, the Irish Sea. There’s a sense of being ancient, from Fair Isle to Faeroes.

I went to a talk last week for Sonica Fest where a girl from Fair Isle talked about climate change, how her home island would probably one day be swallowed by the sea. I can’t help picturing a Cocteau Twins song when she says it. She dropped handmade bronze chains in different oceans so you could see the divergent levels of oxidation, relative to saline content. It was beautiful, this abstract material rendering of elemental time. The world rusts differently; we are all objects, exposed to variant weathers. Her name was Vivian Ross-Smith and she talked about ‘islandness’, a project which connects contemporary art practise with locality and tradition. The term for me also conjured some sense of the world as all these archipelagos, whose land mass is slowly being ravaged by warming waters. The pollutants we put in. Islandness betrays our vulnerability, the way we were as 12-year-olds at the mercy of the tides, the weather and our gruff skipper. I had little conception of what climate change was, but even then I didn’t set a division between humankind and nature.

Back on the boat, I traced my own moods in the swirls of those mysterious currents, dipping my fingers in the freezing North Sea. Who are we before puberty, pure in our childish palette of pastel moods? When I think about how that sea spreads out to become the Atlantic, so vast and impossibly deep, I grow a bit nauseous. Maybe that’s the sublime; an endless concatenation of seasickness, feeling your own weakness and smallness in the face of great space, matter, disaster. How easy you too could become debris.

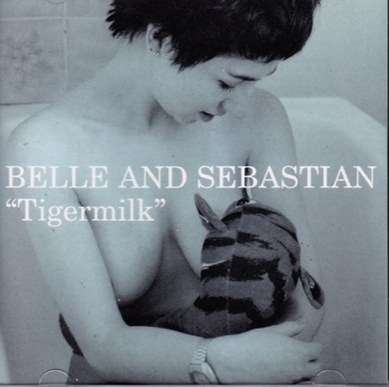

Increasingly, that waltzing Cocteau Twins song feels more like an elegy, haunted by the shrill of soprano, those shoegaze guitars resounding like notes through a cataract. A line from Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’* I always remember, ‘The sounding cataract / Haunted me like a passion’. Interplay between feeling and form, sound and vision. The ocean warming, the beat steady and mesmerising. Are we sleepwalking into the Anthropocene, over and over again, a lurid repetition compulsion? Why we keep burning up fossil fuels, emitting our plumes of carbon, senseless in the face of a terrible sensorium? I crave solid objects that show up the archives of history, those plastiglomerates of Frankenstein geology, the warped materials of the Earth’s slow and drawn-out hurting. Liz Fraser’s operatic howls are maybe the mourning of the land itself, begging to be swallowed by the sea. A saving? If originally we came from water, hatched out of amniotic sacks or evolved from subaquatic origins, then maybe we return to its oceanic expanse, its blue screen of death. When I’m anxious and needing to write furiously, write against the tides of exhaustion or time, I listen to Drexciya—Detroit-based techno that harks back to Plato’s mythology of Atlantis, via Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic. There’s this crazed evocation of diaspora, drowning, a mysterious race of merpeople. What evolves below water, what is spawning in the recesses of subculture; what resists the mainstream, the violent currents of everyday life. This subterranean city is a ‘sonic third space’. I can’t help but think of my own other planet, that 12th World separate yet attached to daily reality; somewhere distant but still impossibly intimate. That resonant intensity that drives you from sleep and into midnight discos of the mind, all pulsation of lights, wonder, horror.

There’s a sense that sound itself can be physically embracing. This is maybe how it crosses over into sonic third space, where embedded mythologies flourish in resonant affect. Where sound becomes tangible, making vibrational inscriptions of code upon the body like transient hieroglyphs of an assemblage’s trellising energy. In Tom McCarthy’s novel C (2010), the protagonist Serge is obsessed with hacking the radio to tune into the ether. Alongside the obvious supernatural connotations, there’s a more pressing suggestion that Serge is able to make his entire being become channel for sound. He lays on a ship as I once lay on a boat, listening to the warm stirs, the conversational blips and signals of objects:

The engine noise sounds in his chest. It seems to carry conversations from other parts of the vessel: the deck, perhaps, or possibly the dining room, or maybe even those of its past passengers, still humming through its metal girders, resonating in the enclosed air of its corridors and cabins, shafts and vents. Their cadences rise and fall with the ship’s motion, with such synchronicity that it seems to Serge that he’s rising and falling not so much above the ocean per sea as on and into them: the cadences themselves, their peaks and troughs…

McCarthy’s lyrical clauses accumulate this notion of sound as spreading, seeping into words and orifices, surfaces. Presences, absence. A lilting simultaneity between the movements and pulses of objects. Sound becomes material; is spatialised as cadence, lapping the edge of Serge’s senses with lapidary, enticing effect—always tinged, perhaps, with a lisping hint of danger. The sounds, after all, also evoke the dead. There’s a radio drama by Jonathan Mitchell, where the protagonist has developed a device which allows you to extract sound from wood. There’s the idea that wooden surfaces absorb sounds from their surroundings, and the time and quality of storage depends on the type of wood. It’s a brilliant sci-fi exploration of what would happen ethically if we could extract auditory archives from material surroundings—the problems and possibilities of surveillance, anamnesis and so on. Consequences for human and nonhuman identity, the boundaries between life and death, silence and noise.

https://soundcloud.com/jonathan-mitchell-1/the-extractor

Do the walls hear everything? I think of rotting driftwood, how porous and light it is. How its every indent, line and scar marks some story of the tides, the stones and the sea. Robinson Crusoe, chipping the days away as notches on wood. I think of the hull of that boat, perhaps coated in plastic, sticky with flies and algae.

On the last day of our sailing trip, we were sitting round the table of the cabin, docked in Oban harbour, reading the papers and having a cup of tea. Our youth club leader got a text from a friend back home. She was informing us of the London 7/7 bombings. This was a time prior to having internet on our phones. We weren’t so wirelessly in tune with everything everywhere always. But that little signal, a couple words blipped through the ether, brought the sudden weight of the world crashing back down upon our maritime eden. I had family in London who escaped the attack by the skin of their teeth, a fortuitous decision to take that day a different route. How everything was at once the dread of hypotheticals. I did not understand the vast arterial networks of terror that governed the planet; these things happened in flashbulb moments, their ripple effects making what teachers called history. Somehow it didn’t seem real. Bombs went off all the time on tv; I grew up with the War in Iraq and Afghanistan. Those televised wars were the ambient backdrop to everything on the news. Later, my friends would wile away their teens shooting each other on Call of Duty. It was all logistics, statistics, the spectacle of bodies and explosions. Nobody explained it. We were distracted by MSN Messenger, then those boys with their controllers tuning in and out of conversation, signing online then drifting away into present-absence. X-Box (Live). Signifier: busy. It was good to be away from the telly in the relative quiet of the boat, startled instead by foghorns and seagulls. But even then, we remained connected.

⚓️

The Shipping Forecast has been issued, uninterrupted, since 1867. Its collation of meteorological data provides a map of sorts, a talismanic chart of patterns and movements, currents, pressures, temperatures—something that helps millions of sailors out at sea. I look at such visual charts and truly it boggles me. I prefer grasping such data as sound, delivered in the hypnotic lilt of that voice: its clear diction and poetic pace, calling me home. I think of the west coast, the bluish slate-grey of the sea. Becoming variable, then becoming southerly, rain or showers, moderate or good. Always between things’ becoming, becoming. There’s the pitch-black womb of a cabin again, the childlike promise of dreams and sleep, a genuine rest I’ve forgotten entirely. Listening makes it okay to be again, buoyed up halfway between where I am and where I’ve been. A constellation of elsewheres to placate insomnia’s paranoia; to be in winter’s dark heart or the long nights of summer, endlessly tuning to atmosphere, cyclonic later, slowly veering from the way. My present tense is always eluding, like ‘In Limbo’ with Thom Yorke’s seaward crooning, the morse code of emotion in whirlpool arpeggios, closing and bleeping and droning on a wave far away, the spiralling weather, the fantasy…Another message I can’t read.

*Full title, of course, being ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour, July 13, 1798’.