The word odyssey, like journey, is of course a literal and figurative force. We might have many journeys in our lives, real or imagined, actual or wished for, but how many attain the status of odyssey? What memories, eras and changes must pass for a thread of narrative to thicken as odyssey? Joyce, in Ulysses, showed us we can have an odyssey of everyday life. If you scale things close enough, the simple act of going out to buy a bar of soap is rich with the complexities and diversions and conflictions of odyssey. Wandering the city streets, akin to being lost at sea. Perhaps odyssey itself is more about a sustained act of noticing, looking backwards while intently in the present. Dwelling in memory’s rich oscillations; when we are aware of our lives having epic proportions, imbuing our actions with this freight of consequence. Maybe the more aware we are of our fragile world, or our fragile existence on this world — how proximate we are to a world without us! — even the simple life, so-called, seems massive, significant, difficult.

But I am not here to talk about the Anthropocene, which we are already passing through, wearing within our skin. Finding the label as though a sticker on an apple, formerly known as, familiar variety almost forgotten through ubiquity — well pressed on various surfaces, deferred. It was a Thursday, the day after Storm Ali wreaked havoc on Glasgow, tearing down trees and scattering leaves, stealing what green of summer was left of leaf and letting it blow forth upon roads of concrete — you might say free, if leaves have an internal stammer for separation, a need for self-definition. I’m not sure the beautiful, connected things do. A foliate thought unfinished. I guess I needed to be free as well, there was a lot of text, swimming around me all morning I couldn’t quite fathom. A thicket of text. Dwell upon ellipsis and offline symbols. So I slathered oil on my creaking bike chain, cycled along the Clyde and found myself at South Block studios for a new exhibition, An Orkney Odyssey, by the CAIM Collective. An Orkney Odyssey features the multi-disciplinary works of Ingrid Budge (photographer), Alastair Jackson (haiku), Moira Buchanan (handmade booklets) and John Cavanagh (sound installation). I recently returned from my first trip to Orkney and was eager to immerse myself in something of those islands again.

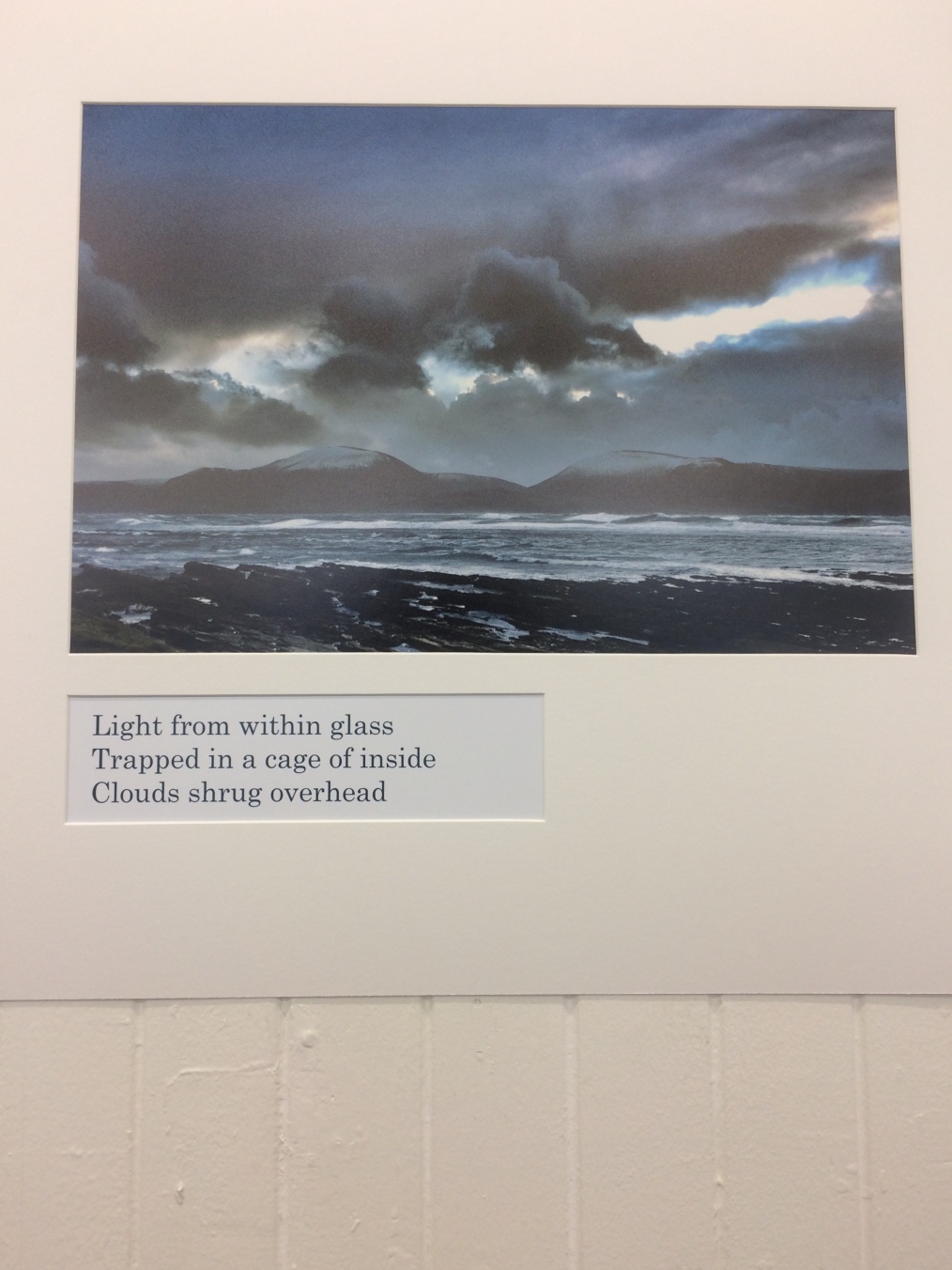

South Block studios is a white room, part café, a place smelling pleasantly of coffee. The rest stop between things, east of town. I’ve been here before with a friend, when we were discussing the early days of a new publication. It feels clean, airy, a place of potential. The exhibition consists mostly of Budge’s photographs, presented along the wall with Jackson’s poetic snippets beneath. I say snippets, because one gets the sense that all these impressions and snapshots are fragments of a broader story, a grander drama. My own time on the Orkney islands was limited to the mainland, but as the ferry curved round past Hoy, I sensed that to really experience life here, you have to think in archipelagos, rather than discriminate, bounded islands. A multiplicity of coastlines connected, reflected, glimpsed across these strips of tide. I experience each piece as both separate and connected: they resemble a sort of Instagram post, the supplementary clue to a world elsewhere, a stop beyond. The possible scroll, the anticipatory mirage of other places, beckoning like hyperlinks.

Looking at these images, I’m reminded of one of my favourite quotes from Susan Sontag’s On Photography: ‘to take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’. Many of these photographs capture landscapes from a skewed perspective, a step away from anthropo-familiarity. We may be unsure where to place our gaze, looking for a horizon or coastline. Sometimes there is a blur, a smudge of cloud and beam of light; a looming mass of weather. An almost unnatural colouring. We are forced to think in terms of diurnal shifts, glitches in time, moments of elemental transition. They are nothing like the picturesque of the brightly saturated tourism brochure, the pamphlets I flicked through idly as I waited for the ferry to Stromness. These images are ghostly, strange, a little ‘off colour’. They challenge my own memories of the unique, misty and windswept atmospheres of Orkney. Budge experimented with different cameras — digital film, iPhone, pinhole — and various chemical processes to capture a sensuous, personal perspective on her native island. She exploited the apparitional potentials of lumen printing, in which objects are positioned on light-sensitive paper and exposed for hours, never quite fully developed. Rather than ‘capturing’ or stilling, rendering her subjects, Budge allows them to unfold in their own way, symbiotically in tune with their luminous environment: stealing its shadows, imprinting a smudge, a glow of time in process. It is almost as though, in taking those photos, she performs a material empathy with climatic change on the island: the shifts in light, all external markings of geologic time and the time of seasons. I am allowed to read into this, because the images abstract from subject, they ask us to find psychic states amid landscape, they do not fetishise the specifics of locality. They do not simply state: here is a field of sheep as we, as humans, see it. They challenge us to rethink perspective, authority, subject and photographic temporality.

Jackson’s poems, which each accompany one of Budge’s images, really draw out this elemental drama of perspective, time and abstraction. Instances of familiar infrastructure become the tuning posts or sounding board for the dead, ‘Ghosts of past talking’ through telegraph poles. Attuned to the nuance of island soundscapes and landscapes, Jackson deftly parses the aesthetic reactions of one object to another, using anthropomorphism in the strategic way suggested by Jane Bennett in her book Vibrant Matter: ‘We need to cultivate,’ she argues, ‘a bit of anthropomorphism – the idea that human agency has some echoes in nonhuman nature – to counter the narcissism of humans in charge of the world’. Anthropomorphism can draw out the multiplicities of sensory experience, crossing the phenomenological ‘worlds’ or ‘zones’ of various enmeshed beings and species.

The haiku might be an appropriate form for ‘capturing’ the Anthropocene because it flickers into being like a sound-bite, it contains a certain authorial anonymity, less of the singular lyric ‘I’ than the lyric I’s environed chorus. Not to mention its traditional association with ‘nature’ as such. Presented like a sort of Instagram caption beneath these images, each haiku seems a transmission from elsewhere, sparking into presence. There are several kinds of aesthetic overlay, a synaesthetic experience of scenes: ‘Glissades and rolls of eighth notes / On a summer breeze’. The smooth legato of wind stuttering up into quavers, could this be birds or the stammering tide where it sloshes in breakwater, interrupts all smoothness of lunar rhythm? I’m reminded of Kathy Hinde’s 2008 work Bird Sequencer, where she worked with Ivan Franco to scan videos of birds resting on telegraph lines into music, after noticing how much the positioning of the birds on the lines resembled a musical score. Each bird would trigger a note or audio sample from a music box and prepared piano, in the manner of a modern step-sequencer: Hinde was literalising a form of nonhuman aesthetic attunement, surrendering compositional control to the whims of the birds themselves, their arts of arrangement. That Jackson’s poetic vision parses the elemental landscape through musical metaphors says something of our ecological inclinations towards attunement. As Timothy Morton puts it:

Since a thing can’t be known directly or totally, one can only attune to it, with greater or lesser degrees of intimacy. Nor is this attunement a “merely” aesthetic approach to a basically blank extensional substance. Since appearance can’t be peeled decisively from the reality of a thing, attunement is a living, dynamic relation with another being.

Since music is our strongest metaphoric apparatus for noticing strategies of ‘attunement’, its poetic invocation allows us to access those processes of intimacy, coexistence and agency at an aesthetic level. The aesthetic level where, as Morton puts it, causality happens: an operatic voice shatters a wine glass, a match smoulders and eats up a piece of paper, the BPA in plastic seeps into the water, alters its chemical makeup, affects the food chain.

This is a fairly minimalist exhibition, despite its multisensory components. It opens space. I can take almost whatever time I want in front of the plainly mounted images and text, the white card a sort of beach I can linger on, skirting the image. These are dark and striking scenes, mostly of nonhuman subjects. I get to share in ‘time’s relentless melt’ as it happens at the pliant, archipelagic scales of an island, stripped away from the carnivalesque rhythms of urban leisure, or capitalist imperative.

Crucial to all this, of course, is Cavanagh’s sound piece. Keen to avoid the bland oceanic ambience of New Age relaxation CDs, Cavanagh makes things weirder. This is the sea but not quite the sea, nature more than nature. Composing or rendering ecological soundscapes requires more imagination these days, a keen ear towards plurality: as every ocean is inflected with both danger and precarity, a poetics of toxicity thanks to our dumping of marine plastics, there has to be an affective current underneath, a mixing of human and nonhuman rhythms, forces, pleasures and tragedies. A force of both presence and loss. Place is no longer one thing, but stamped with the stains of elsewhere. ‘Here’, as Morton puts it, ‘is shot through with there’. Living in a time of hyperobjects means that we can’t think of, say, the seas around Orkney without thinking about the pollution that comes from mainland cities, the energy generated in these waters subject to political decision-making further south, the marine populations around these coastlines affected by agricultural, infrastructural and consumption processes going on elsewhere.

It would be easy to respond to this collision of times, spaces and places with a sort of abrasive, dystopian mix of disorder. Cavanagh, however, responds to the sonic challenge with degrees of beauty, humour and playfulness. His soundscapes swirl around the spoken words of Jackson’s poems, anchoring us vaguely to a sense of present as we pass round the room, viewing the images and poems. Sure, I can hear the waves, the howl of the wind, but these are mixed with a certain distortion akin to kitsch, electronic warp and reverie that glistens with past times, feels retro. This operative aesthetic is achieved with the piece’s main component, an EMS VCS3 synthesiser from 1973: a model familiar to fans of Pink Floyd, Brian Eno and Tangerine Dream. Cavanagh’s music literally ‘translates’ Jackson’s poems and Budge’s images, themselves translations of Orkney scenery, by plugging the syllabic layout of Jackson’s haiku and the locational map data accorded to Budge’s photographs into a patchbay which generates from number sequences a variety of different rhythms, instruments and delay effects. Cavanagh’s ‘authentic’ or ‘raw’ field recordings from Orkney’s landscapes are thus programmed around the audiovisual, semantic stimuli of Budge’s and Jackson’s work. The act of remixing nature in this way exposes nature’s very artifice, a cultural construction dependent upon our aesthetic representations. I think of a very beautiful line quoted in a recent Quietus review of Hiro Kone’s new album, ‘“Nature sounds without nature sounds”’. As a challenge to passive eco-nostalgia, there is an active pleasure in this exposure, in realising the multiplicity and material vibrancy of a term we once took for background and static, mere sonic wallpaper for mindfulness meditations.

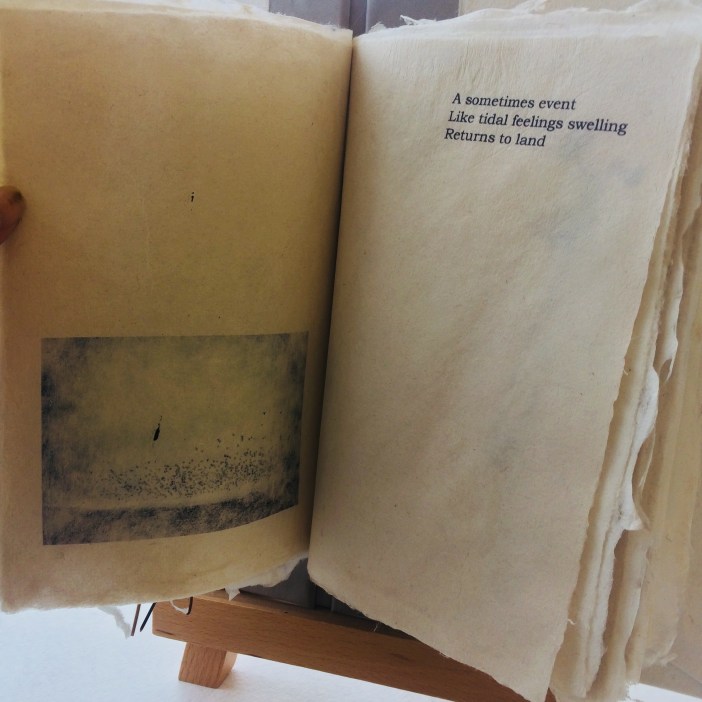

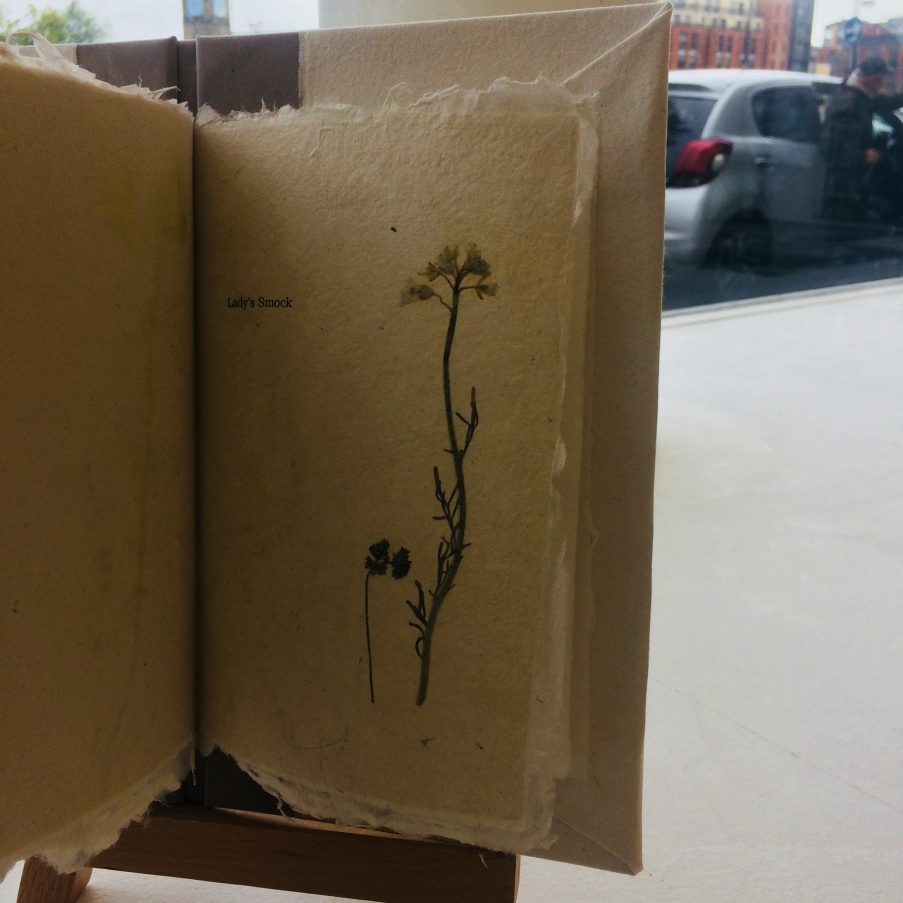

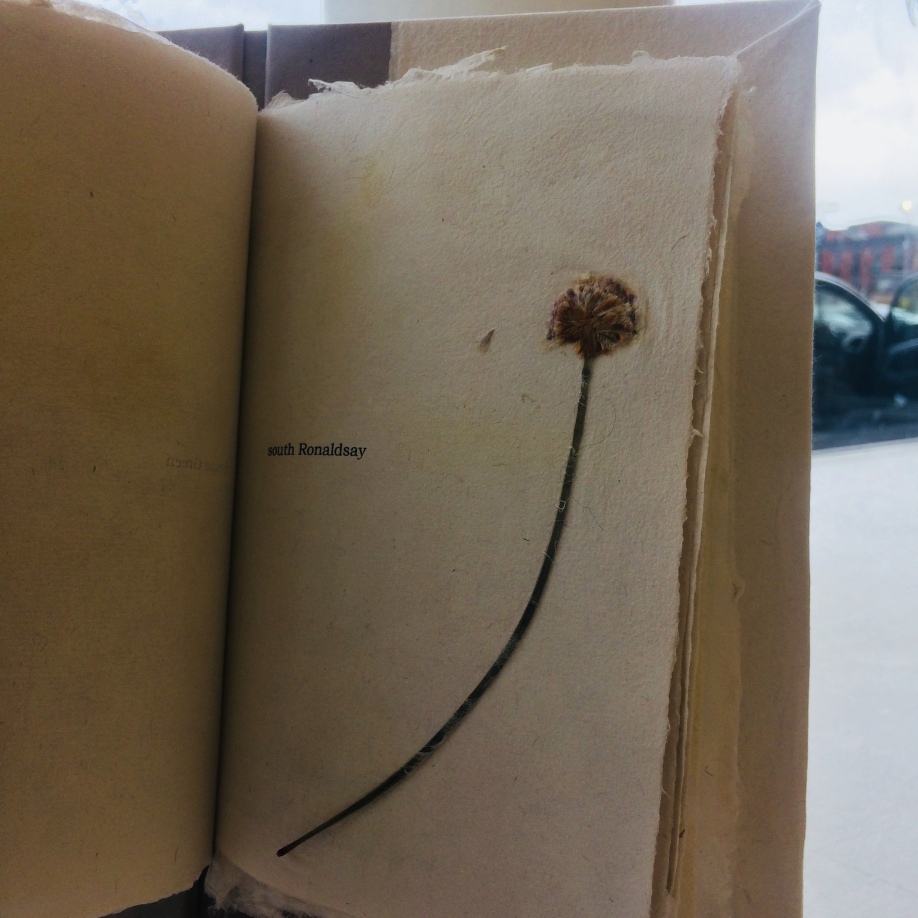

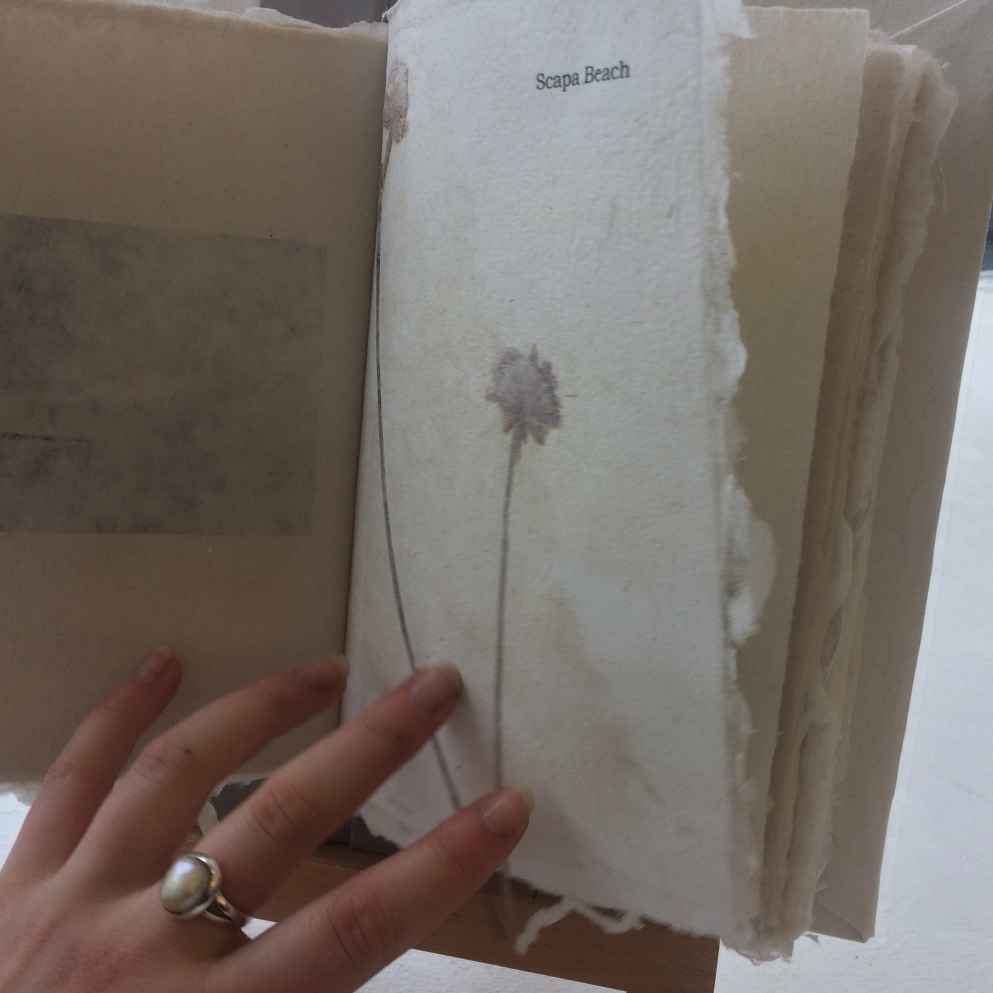

Faced with something as ineffable as the Anthropocene, we often respond, ironically, with lyric excess. The Anthropocene, it gets in edgeways, it knows we are porous. Whose odyssey is this anyway? Exhibitions like this are important because collaboration and innovation are vital means of tapping into the processes by which we, as human observers, might access nonhuman processes, glimpse the scales of time and place in a world where our significance dwindles into material trace. The fossils of future capital, always already fossils. What might a sonic fossil look like, sound like, a ghost trace of retroactive reverie, a broken sonogram, an elegiac bleep of machine or sea? An Orkney Odyssey, for all its portent towards the epic, is actually a rather humble exhibition. It offers the human perspective of memory and affect, holding wonder for these geographies and scenes, but there’s nothing too showy or sublime about it. And the micro focus is important too. Moira Buchanan’s handmade booklets draw us back to the beautiful details of wildlife around us, the simple pleasures in the act of binding and stitching the evidence of our everyday ecologies. She names in her booklets various species and places, prints poems and photos, mingles materials. There’s a real material enchantment here. Rather cutely, I wrote of these booklets before in a post on Buchanan’s 2016 exhibition, All Washed Up:

I think in today’s world, where global warming feels like something vast, incomprehensible, beyond our understanding, it’s so important to focus on the little things. The material details that remind us that we are part of this environment, that the ocean gives back what we put into it. There’s a feeling of salvage to the pieces, whose composition seems to perfectly balance the artful openness to chance at the same time as reflecting a careful attention to arrangement and applied form and texture.

I was still grappling with the Anthropocene with a sort of innocence then. I mean, I was still calling it global warming. The booklets in South Block catch the light of a late September afternoon, luminous in the window. Taking pictures of them, I can’t get the angle or the light right. I can’t quite translate, my iPhone proximate to its physical extinction, stubbornly refusing photographic clarity. During my trip to Munich this year, I was given a five-leaf clover picked from a lovely Bavarian meadow. I pressed it between the pages of Lisa Robertson’s The Weather. That, I suppose, was an act of salvage also. Symbolic recycling. A little token of some unspoken odyssey.

Unsure of the rest of the night, what to do, awaiting replies, I cycle through rush hour, heading south with only vague destination. Peddling hard, I cross the water as though crossing the sea. Later I will fall asleep with electronic sounds rasping my headphones, mixing with the wind outside which batters the window, until sleep becomes its own causality…

***

Exhibition Details:

Venue: South Block, 60-64 Osborne Street, Glasgow, G1 5QH

Exhibition Continues: 14th September – 5th October 2018 (Mon Fri 9-5).