Dear Town Square

My horse disappeared. I had contrived to love the rat

with cheats. Have you considered the ethos

To save your game, pluck acid out of the water;

is communism good code to love you

For bread? In summer I chose the orange grass

with yellow grass, the blue inedible magic flower.

In winter the white grass, blue grass of spring

a verdant seaweed and moondrop flower

Will you take me to school today? I want to learn

the inevitable lesson, in the law of spring/summer

Green-grass fashion, will you describe a toy

flower, sift me from hill, let grow?

I put the wild-grown light in my hunger

I put the coloured grass under soft expense.

I cantered hard across the dream salad

of somebody’s laughter, I lost you

Pinkcat, gathering these flowers afield

before I fell into clement spinach.

If hurricanes come, bless a watering can.

The rats will carry me gently

For every yield of our life, soft rain

the average shipping cost of corn and onion

Or a peach tree dies in the sun

as soon as we receive the foiled mushroom.

Like: then I began making portraits, not just portraits in colours in designs in styles, in blue, in patterns, in abstraction, but this, & I’m trying to describe to you what it was that I was doing. Portraits of the right thickness or thinness, portraits I could retrieve in a moment from my mind, portraits with false bottoms & receding backdrops, false perspectives, like memory, with layers & layers in different shades, in different states of decay, & a whole picture of all of it, first strung out in sections, as though it were on the floor, then pieced together, with some rearranging, and recorded, or put in a place, whatever you like, but in such a way that I then had to again cover & review each part, and handled, taken from place to place, until the right situation was found, as this is the only way to remember where you put something, as you already know, and then, and this is all so obvious, waiting to find out what I had done, so I could begin again. And each portrait, if I can now still describe them that way, each one had some elements which seemed to feed back into the next one. And that this for a while was becoming the most important part of the process. And these portraits, as I’ve tried to describe them, were what was going on in my mind, as far as I can say.

— Bernadette Mayer, Studying Hunger (1975)

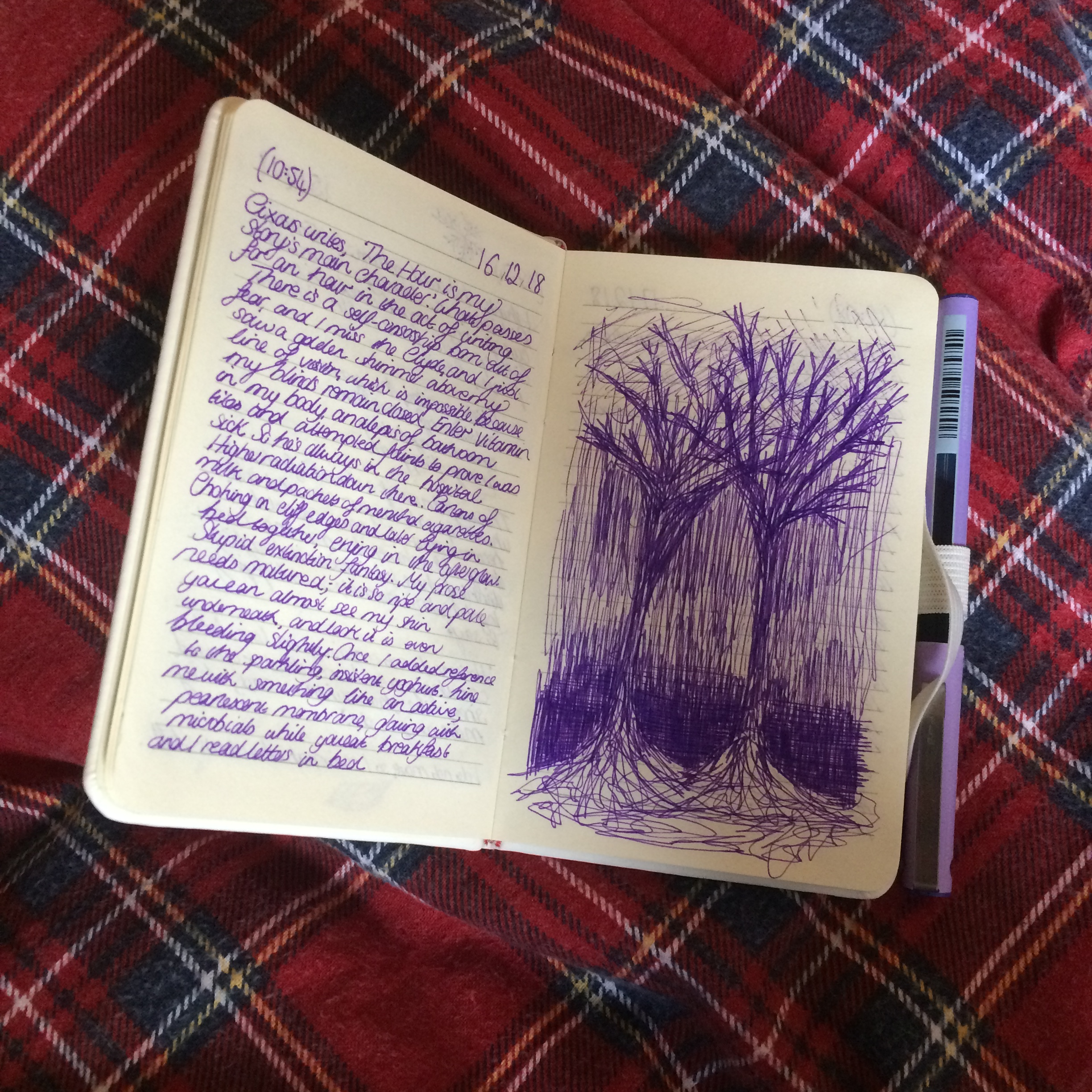

In Studying Hunger, Bernadette Mayer writes of the feedback loops of writing that also comprise a sort of feeding. Reciprocity of materials, bodies that give and are giving, that expel and consume. How different our words might look in hunger. The month brimmed over. Designing these words you could eat, with breath of sweet pastilles, marijuana — scents arise at specific districts. Is this the green haze of Finnieston. I tried portraits too, crazed lines of abstraction, tangles that tugged me into sleep as though sleep were a kindness, a simple feeling. The month brimmed over, it was so much. I lost my appetite, fell into stasis. It was the first December in five years where I had not worked my exhausted ass off, serving tables, sick. I was sick but I wrote instead, through the guilt. I opened your letter.

Most vital when the ink bleeds through the page and the drawings stick together. We drove through the dark with Amnesiac blaring, there was a hot red halo on the night that tasted of whisky, and was empty elsewhere, the emptying streets, the plasma tv.

In Ruchill lies a store called Bammy Beverages, beneath whose armoured shutters lie many dusted bottles of tonic wine, and a key to unlock the sullen underwater future.

‘Pyramid Song’, and the field dark green, last summer’s stoned apparitions of light. A girl beside me just vomiting, vomiting. We stand tall as we can in the glare of it all, watching his hair flicks, the shuddering riffs. I dream of a train ride south and we walk home sick. July is a month impossible now.

(It seems that what I am trying to do with these playlist pieces is akin to Mayer’s portraits. How to depict the month, eking around it, associative entrails. Sketch into negative space the purple lines, the lime green silence. Salad of flavoured sentences, turn over leaf, blogging duration. December with all its aporia, were you good to me?)

I dream of a cooling desert at night, crisp prose like the fronds of a palm tree.

December fills the streets with Christmas, which had come early as early does, November fat on lights already. I write bad things about neoliberalites. I drift around looking at lights in other people’s houses, the extravagance of Park Circus; the way of the Kelvingrove trees, such eerie silhouettes at dusk in the park. An old man stops to tell me where I can find superior trees, more interesting trees. He mansplains arboreal aesthetics to me. I take pictures regardless and slip on my headphones with Spiritualized blaring. He is still muttering about the spirit tree, the one by the Kelvin. I will photograph this tree also, later.

They are selling fir trees in the street, carpets of sweet-smelling needles that haunt the air even after the vendors and their wares are gone. I think of Kyle MacLachlan saying with relish, Douglas firs! down the telephone.

What if a phone call is just millioning ellipses into the night?

So much frustrated reading in annexes, waiting for my little head to just bob into sleep. Avoiding coffee and feeling high on a similar, delirious prose that was not mine. Seek a settling. The stylish oblique mode of writing around your feelings with theory. It is like candy, it won’t dissolve; it is so much about the rush and texture. Bevel my paragraphs, curve all messages.

What cusp of the year is this, or this?

He said he’d flown through the night of a trafficless Amsterdam, four in the morning, eyes like saucers. I could not think of a more perfect event; I need to start cycling again. He said it shaves years off your life, by which he meant it drives you to youth. Sleep does it other ways.

Everything written in the month of August, so vicious. Rejections all round. Flashback to 1998, a date on a chalkboard, the scratch of the white and crumb of time. The playground was a wind-trap and we’d go flying, bearing our jackets as sails. The short day comes, folds itself into the smallest, most elusive square of white. It is a tab I can’t take, so I stay inside; languish in dark, think vodka.

Everyone is on their myriad trajectories, which the lines might fail to capture. Flicker online, line of online over. Try to see y’all before y’all go away. The elsewhere families, unfamiliar.

I felt blessed to have that sliver of access to his mind awhile. After the meeting. It is nice to see the trees like this, enviable spindles of branchware. Sip eucalyptus tea of an evening.

These unheated attics, silicone coffee.

The weather is powder and pretty today, it is so rare I must get outside. Experimental series.

As far as I can say, I want to set tables forever and ever. The people keep coming, it is astounding how many of them exist. As though I could not remember, but then the stamp of each one returned like a flurry of letters, bills, demands of me. They want our stories, bloodthirsty they open their mouths for politeness, performance. They want drinks, pepper grinders, napkins, salt. I take cetirizine because of the dust. I set foot into the building thrice this month. I make cards with pens that ooze gold glitter, smear with black ink my thoughts.

When Christmas lights are blurred in the rain and make me sad, of course I think of ‘Cody’.

A carousel of shoppers and a chance encounter, and we hide upstairs with cups of tea and you teach me how to buy shares on your phone. I watch the little lines zigzag up and down, a portrait of financial temporality. There is this stupid line from a 1975 song I can’t get out of my head: ‘Collapse my veins wearing beautiful shoes / It’s not living if it’s not with you’. Boy whose veins are green not blue. You never require a polish; you are shine. There is heroin in the world again.

Björk’s Vespertine is probably the only festive record we need. It glisters and cocoons me. A friend says it is the Christmas hit for cancers everywhere. I love the harp, the frailest cry, the video with pearls that lace her skin. I want to be lain in a field of dewdrop clover.

It did not snow as promised but it rained a lot. We sat in the cafe for hours and bought little pins with animals on them. There were these gifts. I ate something because it had the word ‘acai’ in it.

Quite a horror to see office workers unleashed in the streets, the drunken invitation to tables, lying about my name to strangers.

That hot needle feeling when you go inside and the heat rushes back to the tips of your fingers. When you wake up late and cough and cough your way through a spinal landscape.

Losing my taste buds. Mustard is recovery flavour.

I am handling the place I miss most. Something about these emails helps me think like a child again. The place where the floor just fell away, exposing that sloshing, hot springs water. And we say one thing, we feel creaturely, we made a wish to capture. It was Ash’s wish to be a trainer forever. Someone says I look like an anime character, the high-waisted jeans thing, luminous t-shirt. Read old notes and the only good line I wrote last year: ‘a breath rent asunder by mystic cat Pokemon’. So much still to recapture.

I think about Carrie & Lowell I think about William’s Last Words I think about A Silkworm of One’s Own. There is a funeral, an offer for coffee, a small admission, a kiss on the cheek.

Excruciation at personal mannerism, listening back to the interview.

We sat by the fire and talked awhile.

We sat by the fire with wine.

We sat by the fire and it rained outside.

She didn’t even buy me flowers, she didn’t even think twice.

My mother swears so much better these days.

An expansive hamper arrives in the post.

When you leave, and the air hits your face.

The city is emptying. True nocturnalism is listening to Jason Molina in grim mist of rain, on your way to Maryhill Tesco at 2am. The workers sit smoking in the carpark, scrolling on phones. It was funny to leave with bagfuls of vegetables, ache in my chest, ironically playing ‘Perfect Day’. When he said we looked stunning and suddenly it was Christmas again.

The air just smelled of fish and chips. Comfort of a town I used to call home.

I awoke to my alarm clock, which wasn’t a pop song and it wasn’t that loud. We walk along the river, catching the fog. It was so nice to see you! Victorian bridges house numberless ghosts, and we pass between. I leave my green scarf in a bar and rush to retrieve it the following morning. It is never loud enough, warm enough. I write this essay about lines and Derrida and the work of crying. Nobody drinks Sangria round here.

Sauchiehall hellscape.

If I live to your age and in what situation.

Listen to the Morvern Callar soundtrack on Christmas Day, paint my toenails blood red like a call. We trade solstice poems online. Full moon energy of weekends, and how we sat in Category Is on Saturday reading from Midwinter Day, this quiet ritual of voice and warmth. Homemade treats and spiced orange tea. Passing the book around. Catching myself on the science vocabulary, lush words of reaction, wishing I could roll my r’s like him. You should just write, just write everything.

It is so nice to see you all. Candid photograph, conversation.

One hand

Loves the other

So much on me

Try to write to make myself hungry. I learn this word petrichor, which feels like a word I already knew — I can taste it. Softest, resonant earth elsewhere. Takes shape in your message. Remember teenage wanders, unruly longing, misdirection. Sweetness.

I walk north, west, home. I walk through the rain and my brain is sparkling. The year does not simply ‘close’. It is a recurring dream. The city just shimmers as temporary portrait, and I add the blue to accentuate insomnia — a little violet around the eyes, significance of the Clyde as a river. How to write about those I miss? What a year it’s been, we say each year. Christmas, so we’ll stop, surely. The way the BBC lights looked, pregnant in fog in the picture. The river drags through us, the ones it swallowed. Everything just streaming and streaming, the way winter goes.

~

The 1975 — It’s Not Living (If It’s Not With You)

Let’s Eat Grandma — Falling Into Me

Perko — Rounded

Sharon Van Etten — Jupiter 4

Deerhunter — Element

Stereolab — Blue Milk

Björk — Heirloom

Oneohtrix Point Never — Last Known Image Of A Song (Ryuichi Sakamoto rework)

aYia — Ruins

Mogwai — Mogwai Fear Satan

Swans — Oxygen

Peter Broderick — Carried

Kathryn Joseph — Cold

Conor Oberst — The Rockaways

Frightened Rabbit — It’s Christmas So We’ll Stop

Sufjan Stevens — Lonely Man of Winter

Angel Olsen — If It’s Alive, It Will

Damien Jurado — Over Rainbows and Rainier

Penguin Cafe Orchestra – Thorn Tree Wind

William Tyler — Call Me When I’m Breathing Again

Phoebe Bridgers — Friday I’m In Love (the Cure cover)

The Delgados — Coming In From The Cold

The Verve — Virtual World

Spiritualized — Cop Shoot Cop

Observations of Sky

[Exercise in which I recorded the sky over nine days upon waking.]

10/3. The sky today is a grey recalling opals. Something of a swallowing grey, an inversion of light. An all-consuming, elderly grey. It feels smooth enough to resist osmosis and yet it manages to yearn its way into you, needling the soul. A grey that knows mortality, even as it gapes its ceaseless ugliness. A grey you’d pearl into a necklace, then hate it.

11/3. The sky today is the slightly off-white of old furs, you know the kind that’ve been festering in vintage shops a little too long. Demographic time-bomb. Once clean bleached, now a bit lossy on the gleam front. You couldn’t picture Kate Moss starrily circling a red carpet in this kind of white. It’s sorta depressing; an off-white mother’s day. Facelift.

12/3. The sky today is white again, but the kinda white with a glow behind it, promising future glimpsing blue. Maybe that’s an audiovisual effect of birdsong, deceiving me as to the premise of spring. The sky is a white that goes on forever. You have to lift yourself up mountains to see where it breaks into greys and golds, watercolour perimeter slowly blurred.

13/3. The sky today is spread with the aquarellist promise of blue. It is still early, before 10am and there is hope for sunlight later in the day. It is a true March morning, the kind I remember from beautiful hangover walks two years ago, savouring the fact of my company and an energy I’m sure I didn’t deserve. Spiralling & dashing like a girl again, not needing a drop of anything. The clouds are faint but everywhere, leaving the blue slightly mottled beneath and I think of canopy shyness–left faintness of yesterday’s rain which I missed anyway, being inside all day. Imprinted silhouette pretty. It is hopefully a blue for opening daffodils.

14/3. The sky today is grey again. This is the unmistakably fatty grey that speaks of climatic sickness. It is grey going backwards, clustering soot upon styrofoam. Some elements clicked together to make a nasty residue, spread like paté or peat across where clouds might be; but no gaps in between, no alterations of colour. It is all the same grey. It is all of a thickness, bubbling. I wonder who clutches the knife to prise it.

15/3. The sky today is grey again, but imbued with a stony blue within it. Tricky to explain, a certain weight. Completely opaque. Maybe algaeic. Can hardly imagine it ever breaking again, breaking to blue. I find myself longing for that Frightened Rabbit b-side, and the line, Well the city was born bright blue today. Clacking my feet upon fresh pavements; the westerly smell of warm tar, marijuana. Maybe I’ll wake up soon to that topsy-turvy, luminous feeling. It is like somebody took wax and ripped off the beams of sun, so all that’s left is the gluey residue, sweat-stained and delirious between earthly dimensions.

16/3. The sky today is a discharge grey, clotting so gross into its own thickness. It has not broken for days beyond sprinklings of rain. It is a turgid and bodily grey, waiting to burst. It is a hundred mixed-up medical metaphors. I listen to the pale road roar and the twinkles of sparrows. Mostly the sky is just grey though. I watch a video of people kissing inside cellophane.

17/3. The sky today is much more blue. I dream I bought cornflower underwear. Oh, this blue. Powdery and fragile, but blue nonetheless; you can see it made out against white patches of cloud that are not quite summer white, cotton white, but white of a sort. It is such a relief for this briefness of blue. Blue you might achieve something in, except I am so tired I succumb to rested eyes, closed lids, the watery exhaustion that leaks between lashes like a great whale expelling its plankton, mistaken plastic.

18/3. The sky today is heavy as a belly about to give. It presses down, sags with white. I hope somebody administers a drip to silently remove its snow. Through the back entrance, back to heaven. I cannot handle any more snow. Never mind silent spring, what of invisible spring. All the frost and snow crushed out the crocuses. Will I even see a single row of good daffodils this year? I fear I won’t. I am reading Dorothy’s journals for practice, or some sort of vernal supplement. Of course more skiffles start drifting, but it wasn’t supposed to snow after 1am and now it’s 11:11, the witching minute, and I can’t help but wish for a flourishing kinship. The sky will resolve its millioning creases into further whiteout loneliness, so I make do down here, terraforming my future.

Short story I wrote this morning in dedication to January, something about blues and time, memory, the struggle to piece yourself together…

*

It is a nightmare to wallow in all this time. She professes inwardly, however, a sense of relief at the expense it affords, all the things she might do or watch or read. I might pick up a book at random, take it to a café and just blitz it, you know? She uses the lighthearted, daytime tv voice in her head—semi-ironically. When she bumps into someone she knows, her eyes swim with gratitude. This is something she must stop.

It is January and no-one is doing anything really, just working. She is working too, except she gets minimal shifts. So really she is treading water.

It would be better, perhaps, to change the scenery. The man at work that paints the stage sets for the plays, he recently had a baby. That baby will grow up, she thinks, surrounded by boards of painted landscapes: haunted houses, verdant meadows, pastoral castles, seashores and fairytale forests. There will always be another reality, overlaid with this. She recalls being very small and trying to wrap herself into a book, almost physically. She would read in the shadowing confines of the wardrobe doors, read dramatic fantasy stories with grownup imagery and worlds the size of universes. In each book she nurtured a personal metamorphosis; maybe the worlds mattered less than the characters. There was this longing she didn’t understand, like nausea. The boys in these books always had eyes described as gemstones, like He looked at her with his hard and sapphire eyes. As a result, she finds herself mostly drawn to men for the colour of their irises. She especially likes the rarity of green, but two-tone eyes are nice as well. She knows a couple of people with heterochromia, and this is a word she relishes, its gorgeous vowels and subtle moans. The O sound.

It is stupid to describe people with eyes like gemstones. It is so obvious. More often, perhaps, they are like television sets, endlessly flickering, reflecting. Melanin, melanin. She turns it over, listening for it like the jingle of her many secrets.

There is just this expanse of time. She walks through the park again, where everything is bare and swept back and any remnant of leaf is like weetabix mushed in dark chocolate, fudge. There is nothing to kick away, nothing to admire. It is all such luxurious waste. This is the bench they sat in, kissing under her black umbrella, the day before things fell apart. That was two years ago now, so she hardly remembers the thaw in her chest when it happened, the way it spilled out like rain. This is the bench where she sat with her pal, six years ago now, and her pal was eating a panini from Gregg’s and it wasn’t vegetarian because she wasn’t, then, and they were watching the belligerent squirrels and it was all so wholesome. Then.

Climbing the hill raises heart rate. When she reaches the top there is such a release.

She wishes she was the type of girl to have a favourite café. Like, Oh this is where I go to relax or study. She sees these girls everywhere, shiny-haired and always smiling with MacBooks and frappuccinos in university brochures. They are so glossy, these girls, they are like anemones. They stick. Boys love them, clubs love them, gym memberships love them. They will glow and smother at will, with their gelatinous, rosy lips. As for her, she is more like a stickleback: swept in and out by mysterious tides, inhaling small quantities of plankton and other fragments of life. When this thought occurs to her, she googles the species: spinachia spinachia; sea stickleback. In Latin, it sounds like some Italian dish, but ah, the brutality of Wikipedia: ‘It is of no interest as a commercial fish.’

The shape of her career dissolves as in ink; she laughs at it, frequently, in bars with friends. Faces the details later, in sleep, where they rise to the surface, inexorably.

She picks up her pace, trying to escape the park where the children are being released from school and are swirling in gregarious shoals around her, screaming at the swings. I am not a commercial fish, she recites, over and over, twisting a smile. Sometimes it is good to get mixed up in these currents, wishing she was small enough to join in, or at least perfect the evolutionary acts of disguise and disappearance. Children communing their wisdom, every howl a perfect hour. For an hour is so much to children. An hour is so much to her; but not right now.

The alarm clock makes her scales ache daily. There is no reason to keep it on, but then again no reason to turn it off. The singular guarantee of diurnal rhythm. Her body is always late, so each time the blood is a dark surprise. She sees it spreading through the week, flowering outwards, like an idle fantasy of slitting one’s wrists in the bath. It is in my nature. Once, high at a party, she studied the arabesques of wallpaper, thought of the blood and tried to describe it when no-one was listening.

Daily she scratches at the elastic canvas of her skin, wishing sometimes she could shrug the whole thing off. She pictures the underneath as this diaphanous mass of sadness. You could only catch it in a blink, like a plastic bag snagged in a tree. A soul without skin gets caught on things.

The days are like videotapes. She takes the same one off the shelf and rewinds it daily. Out of the same, the red blue green, she will eventually find the perfect day, the perfect tape. The girl unwound inside of it. For now, all the good things are just pieces and snatches and moments, like broken-up Snapchat stories she can’t get back. Every replay betrays the truth of the memory. The boy that used to send pictures from abroad, shots of skies and doorways, what did they mean?

Late afternoon, and still nothing. She knew people that walked dogs in their spare time, cash in hand. People that did internet surveys for easy PayPal transfers. People that chanced a few on low-level gambling, even though they weren’t remotely into sports. She recalls a singular night at the casino, five in the morning, gingerly sipping pints of Tennents while he put coin after coin on the slots. It was Christmas and the tips were good; they came in fat bags of new pounds with the edges you could bump twelve times with your thumb in rotation. Metallic tastes, a key of Mandy. Pop songs and the sound of the rush itself, the beginning which kept on beginning. She supposes that’s what love is, for a while.

Nobody she knows is in the park, it is disappointing. Finnieston is where the sun goes down, so the streets are dusky and violet, save for the neon allure of sushi bars, chip shops. Everyone crowded inside so the glass grew steamy. She walks on the long road, chasing the vague direction of town, evading the afternoon. She is walking, pointedly, to acquire a sense of hunger. There are days when she is always hungry, days when the numbness swallows her appetite. Sometimes she can’t decide. She remembers a time when all people did was tell her to eat. That was a while ago—she deserved it then.

Now she sits at the window, night after night, cracking slabs of discount chocolate. This is something she must stop.

Feels good to say a cold one. He calls her at three in the morning but language is too raw at this point, so she keeps her phone on silent. The light in the window opposite is flashing on and off, like a signal. The world is always on the brink of breakdown, or disco.

It is a nightmare to just wallow, wallow, wallow. To turn the connections, to retrace each tread. Satellites above tracking her every location. Then a text message, the gaze of a stranger, vibrations. It is enough sometimes to just be acknowledged.

One day she will polish her gossamer scales, she will shimmer to the lights and dance in a prism of beautiful irises. Her great disappearance—captured on videotape, spinning away.

I’m walking home, stuck on a narrow pavement, hemmed in by parked cars. Two men are dawdling ahead of me, both of them huffing cigarettes. They’re dirty fags, definitely Marlboros, a stench that’ll take out your lungs like a morning bloom of toxic frost. I feel nauseous as the smoke blows back in my face and it’s a struggle to breathe; I’m striding fast to get ahead of them, not caring at this point whether it’s rude to push them aside. My heart-rate is up too much, the bodily reaction palpable.

I’m in a friend’s flat. It’s July and we’ve been awake all night and now it’s 4pm the following day, three of us watching videos, drinking rum with blackcurrant cordial in lieu of food. Somebody rolls every hour or so; two of us smoke out the window. It’s been raining for weeks but today the sky is blue and the daylight sparkling. A warm breeze comes through. I’m reminded of the night’s shimmery feeling, a glorious cocktail of chemicals and dropped sugar levels producing slow-release euphoria. The cigarettes are neatly rolled, thin and compact. They don’t take long to smoke, but the two of us—not being proper smokers—relish and linger the moment of supplementary respiration. They don’t taste of much at all, a very faint tobacco flavour that twirls down our throats, the thing we’ve been craving all night. We take turns to gaze at the street below, a couple of lush-leafed trees, passersby offering glimpses of the reality we’ve temporarily dropped out from. Everything has that vaguely pixellated feel of the virtual. Sideways glances at each other’s faces; at times like these you notice the colour of eyes, the shape of noses. We’re listening to dream pop, hip hop, lo-fi. We gossip to forget ourselves, spark grand discussions on topics ranging from astrology to engineering to ghosts. There’s a certain ambience we’ve made out of pure haze, a hilarity of mutual laughter meaning nothing in particular, resounding through abyssal chains of meaning. It’s one of the most blissful afternoons of my life. I go home, hours later, still tingling with nicotine. I lie on my sheets and let the scenes flicker by like beautiful lightning.

Like many people, my relationship to smoking is a little complicated. I’m a Gemini, my loathsome desire always cut into halves. I find myself disgusted by the dry sharp smell and residue taste, but somehow addicted to the presence of cigarettes in narrative, their signifying of time, their eking of transition between moments. It feels natural that such action should then manifest in real life: the disappearance outside after a talk or song or reading, buying yourself time to mull things over, return anew—snatch chance interactions with strangers. I know a friend who started smoking at university purely for the excuse to talk to girls outside nightclubs. I guess it worked well for him. The universal language of the tapped fag remaining a perpetual possibility, footsteps approaching the rosy garden of your smile and your smoke, your contemplative aura. Veils over nature. This is nothing but nothing; this is just the vapourisation of time and space. Smoke gets in your eyes and reality feels smoother. Less needs to be said; intrigue can be held. You add that plenitude of mystery in your walk, your dirty aroma of cyanide, carbon, tar and arsenic—an edge above the vaporous plumes of sweet-smelling e-cigs. With a fag in hand, there’s less impetus on you to talk. With a vape in hand, people want to know about your brand, juice, flavours.

A Smoker’s Playlist:

Mac DeMarco: Viceroy

The Doors: Soul Kitchen

Nick Drake: Been Smoking Too Long

Sharon Van Etten: A Crime

Simon & Garfunkel: America

Oasis: Cigarettes and Alcohol

Otis Redding: Cigarettes & Coffee

The White Stripes: Seven Nation Army

My Bloody Valentine: Cigarette In Your Bed

Tom Waits: Closing Time

Neil Young: Sugar Mountain

Smoking is an object-orientated approach to daily existence. A way of distilling the Bergsonian flow of time into its accumulative moments, paring apart the now from then in the spilling of ashes—slowing and building anticipation by the mere act of rolling. Appropriate that Bergson should use a rolling, snowballing metaphor for temporality. To roll a cigarette is to accumulate a fat tube of tobacco, to acquire something that smoulders, continues, then what? Flakes off as snow, delays. So you interrupt the flow, so you start again.

Denise Bonetti’s recent pamphlet, 20 Pack (2017), released via Sam Riviere’s If a Leaf Falls Press, explores the temporal and bodily effects of smoking. The title itself relates to a deck of cigarettes—twenty once being the glut of an addict’s indulgence, now the standard legal purchase—but of course you can’t help thinking of a deck of cards. Especially since the numbered poems are all out of order, starting with ‘20’, finishing at ‘1’; but by no means counting down in order in-between. I think of Pokemon cards, Tarot cards. We used to play at school and you’d always ask how many in your opponent’s deck, like “I’ve got a 20 deck, want a match?”. With Tarot, I don’t think we understood that only one person was supposed to have the cards in hand. We probably triggered some real bad luck, doing that. Bringing two realities, two predicted futures, into collision. Messing up the symbolic logic. I always flipped over the sun card, savouring the dry irony of Scottish weather and clinging to that vibrating possibility of future joy. We swapped velvet tablecloths for the scratchy asphalt of playgrounds. The older kids drifted on by the bike sheds, wielding cigarettes, watching us with scorn and suspicion.

Smoking has a lot of symbolic logic: ‘the faith in the liturgy the telling of a story / the pleasure of knowing what’s coming’. This is a whole poem from Bonetti’s collection: number ‘4’. A liturgy being a religious service but also a book. Cigarettes are made out of layered paper, scrolled possibility, something to become enslaved to. You just smoke your way through them, the way you might blaze through a novel, find yourself drifting on down a webpage. What thoughts roll round your mind in that moment, churning as soaked clothes in a launderette? You rinse them by the final intake, stubbing the line out and switching your mind like a refresh key. Take it off spin cycle and have a breather. Knowing what’s coming is that sweet anticipation, first cigarette of the morning, of the night or the shift. Remember what’s good for you. Physical relief disguised as imminent pleasure.

The poems of 20 Pack are quite wee poems, thin poems, poems with space inside them, milling and floating around the language. Punctuation is often erased to allow lingering where one pleases. These poems negotiate geometries of thought and situation, honing on imagistic visions which score upon memory: a seagull’s beak, swimming pool tiles, a gold leaf or ‘terrible sequin’, the sun and moon, ‘cyanic peas’. There’s the oscillations of desire, an almost mutual voyeurism that invites the reader within this intimacy, controlled as the cold celestials then warmed with a little wit. Each cigarette is tied to these ‘songs’, lamenting ‘the self- / replicating minutiae of days, / nights, encounters’; ‘An act of anachronism’. Every cigarette involves that mise-en-abyme of re-inhabiting each moment you once smoked in before, a concatenation of places and tastes starting to merge together with the first inhale. This is the seductive literariness of cigarettes. As Will Self characterises it, ‘it’s the way a smoking habit is constituted by innumerable such little incidents — or “scenes” — strung together along a lifeline, that makes the whole schmozzle so irresistible to the novelist’. Maybe also the poet. Easy to make necklacing narratives from the desire points instated by the gleam of a lit cig on a cool summer’s night. The worried observer or reader, clicking the beads together, watching with interest for events to slide into effect. The imminent possibility inherent within the duration of a smoke: what happens next? The loose stitches of a poem you pull apart for a better look, a glimpse of the future. Is all poetry a signal from tomorrow, that fragment of what comes next in the rolling tapestry of the present?

Simultaneous acts:

A tobacco impression between two movies,

Fingertips brushed in the exchange of a lighter,

Expendable tips,

The thick lisp of silver foil,

Dark cigar husk of Leonard Cohen’s voice,

Where we hid from the rain, making miniature glows.

In Ben Lerner’s 10:04 (2014), a novel set in New York, poised on the brink of various recent storms, streetlights provide a sort of talismanic portal into other dimensions. The text’s obsession with Back to the Future plays out the film’s time-travelling logic of multiple temporalities colliding, but it is light that figures this as fiction’s possibility. Embedded within 10:04 is a short story titled ‘The Golden Vanity’, in which the protagonist is struggling to write a novel, an echo of the narrative arc of Ben Lerner’s text. The protagonist pictures his protagonist standing at the same ‘gaslight’ beside which he stands in Ben’s (10:04’s narrator) fiction: ‘he imagined […] that the gaslight cut across worlds and not just years, that the author and the narrator, while they couldn’t face each other, could intuit each other’s presence by facing the same light’. The vicarious union of all these writerly characters, standing at the same gas lamp in different points of real and fictional time, enacts this sense of immanence contained in (re)iteration. The lamp embodies this externalised marker of being—resembling the narrative I that cuts across the novel’s page.

We might think of Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own, describing the appearance of a shadow, a ‘straight dark bar, a shadow shaped something like the letter “I”’. It’s difficult not to think of the extra implications here: a straight dark bar is surely more than just a crudely drawn line on a page? Maybe also a heteronormative public space in which strangers meet under gloomy mood-lights, exchanging phone numbers and slurring words? There’s the association between the male voice and the act of smoking. How many times have you seen a male writer smoking onscreen, or in a novel? Is smoking an act of masculine dominance or, as Bonetti seems to suggest, a more fluid ‘act of negotiation’? Woolf writes: ‘One began dodging this way and that to catch a glimpse of the landscape behind it [the “I”]’. Like the emanating smoke of a cigarette, the literary I dominates context and setting with its insistent perspective, its rationalised display of determined personality. How can we see the fading moors, the elaborate trees, behind the I’s lament? What is it that recedes beyond the smoky planes of our everyday rhizomes, stories trailing over one another with a certain lust for narrative, precision, suspension—self-perpetuating molecules of thought? In poem no. ‘8’, Bonetti relays a ‘text from max: “i can’t stop picturing my first fag break splitting into a chain of identical fag breaks, each reiteration carrying a fainter trace of the initial reason”’. The pleasure of focus dwindles like a tiny dying seed, until all that’s left is this black, Saturnal kernel, reflecting outwards the rings of former moments.

Things people have spoken to me about in smoking situations:

Family problems,

Sex and relationships,

Hunger,

Literature,

Politics,

Parties,

Mental illness,

Makeup,

The ethics of cheating,

Shared memories with deeper resonance beyond initial palpability.

Like some subtle, truth-telling elixir, cigarettes invite a space for confession. As Self argues, cigarettes are great for novelists. Not just because of their magic ability to garner stories from others, but because of their Proustian resonance. Gregor Hens, in his beautiful memoir essay Nicotine, describes the focus of smoking thus:

The chemical impulse initiates a phase of raised consciousness that makes way for a period of exhausted contentment. Immediately after the first drags an almost unshakable focus on what’s essential, on what’s cohesive and relatable sets in. I often have the impression that I can easily link together mental reactions to my environment that serendipitously arise from one and the same place in the cortical tissue during this phase. This results in associative and synaesthetic effects that help me to remember, along with the dreamlike logic that is the basis of my creativity.

The ebb and flow of a cigarette’s biochemical culmination prompts a certain rhythm of consciousness conducive to the rise and fall of creative impulse. Little flash-points of mental connection are made with each spark of a lighter; while joining the serotonin dots the nicotine rush soothes us into a mental state of dwelling, which allows those perceptions and expressions to take shape from the swirls of smoke. Consciousness lingers thirstily in the moment.

With an existentialist’s recalcitrant cool, Morvern Callar inhabits her eponymous novel by Alan Warner by describing the scenery around her, narrating her actions rather than inner feelings. Frequently she ‘use[s] the goldish lighter on a Silk Cut’—the phrase is repeated with little variation at least 30 times across the text. It’s a touchpoint of continuity in her turbulent world of suicide, secrets, solitude vs. claustrophobic community and most importantly the whirling raves of the 1990s in which you shed your identity. The rave scene itself ‘is just evolving on to the next thing like a disease that adapts’, as one of the ‘twitchy boys’ on her Spanish resort relates. Cigarettes are perhaps the little quotidian landmarks, the tasteful eccentricities that lend temporal solidity in a late-modern universe that warps and sprawls like some viral code, recalling the human ability to transmogrify base materials. Turn manufactured product to curls of paper, smouldering ash. Cruelly ironic, then, that they cause cancer—the terrible cells that twist, coagulate, balloon and elude.

Every cigarette recalls a former cigarette, the way you might look into the eyes of a lover and see the ghosts of all those who came before. That uncanny glimpse of deja vu that is human desire, the algorithmic infinitude of selfhood. Cue Laura Marling ‘Ghosts’ and sit weeping youthfully into your wine, or else think of it this way, as William Letford writes in his collection Dirt: ‘If you’re lucky you’ll find someone whose skin / is a canvas for the story of your life. / Write well. Take care of the heartbeat behind it’. You might never find a single soul whose skin provides the parchment for your ongoing sagas. Maybe you will. Maybe they smoke cigarettes and so you try to tell them to stop, thinking of their poor organs, struggling within that smoke-withered body. Maybe you’re single and lonely, writing as supplement for the love that’s trapped in your own ribcage like so much bright smoke waiting to be exhaled. There are many mouths you try out first. Poems to be extinguished in a crust of dust and lost extensions. Maybe you don’t think of it at all.

On average, romantic encounters triggered by a shared cigarette:

3/5

+ one arm wrestle,

a distant sunrise,

a song by Aphex Twin,

a bottle of gin,

a fag stubbed out drunk on the wrist.

We tend to think of cigarettes according to the logic of ‘first times’. Again that elusive search for origins, innocence. I remember doing a creative writing exercise long ago where we had to write, in pairs, each other’s first times. Others tackled drunkenness, kisses, flying, swimming. For whatever reason, the two of us (both nonsmokers) chose smoking. My partner recalled being at a festival, aged sixteen, being passed a rollup by her older sister. She remembered the smell of incense, coloured lights, the little choke in the crowd that signalled her broken smoker’s virginity. I slipped back into the dreary vistas of Ayr beachfront, sheltering from the sea wind with a couple of friends. This tall girl I looked up to in ways beyond the physical realm passed me what was probably a Lambert & Butler and I remembered being so pleased that I didn’t cough, but probably because I swallowed the smoke greedily and didn’t know how to inhale properly.

It took me a while to learn how to breathe altogether; when I was born I almost died. The first smoke feels like an initiation into identity and adulthood. It was like coming home from somewhere you never knew you were before. That little spark, a doorbell deep in the lungs. You purposefully harm yourself to establish a cause, a chain reaction. Realising the strange, acidic feeling flourishing in his stomach after smoking his first fag as a child, Hens suggests that ‘in this moment I perceived myself for the first time and that the inversion of perspective, this first stepping out from myself, shook me up and fascinated me at the same time’. It’s hard not to think of the bulimic’s first binge and purge, the instating of shame and pleasure whose release enacts this sweet dark part of the self, an identity at once secreted and secret. Feeling the little spluttering sparks or tingles within you, you realise there’s a thing in there to be nurtured or destroyed. As the bulimic’s purge renders gustatory consumption material, a thing beyond usual routine or forgotten habit of fuelling, the smoker daily encounters time in physical context, the actuality of habit, transition. From the perspective of his spliff-huffing protagonist in Leaving the Atocha Station (2011), Lerner puts it so eloquently:

the cigarette or spliff was an indispensable technology, a substitute for speech in social situations, a way to occupy the mouth and hands when alone, a deep breathing technique that rendered exhalation material, a way to measure and/or pass the time. […] The hardest part of quitting would be the loss of narrative function […] there would be no possible link between scenes, no way to circulate information or close distance […].

The cigarette is Jacques Derrida’s Rousseau-derived dangerous supplement, the elliptical essence of what is left absent but also implied. The three dots (…) or flakes of ash left on the skin from another’s cigarette. Are we adding to enrich or as extra—a thing from within or outside? Derrida describes the supplement as ‘maddening, because it is neither presence or absence’; ‘its place is assigned in the structure by the mark of an emptiness’. We find ourselves entangled; we smoke because we want to write, move, kiss, drink or eat but somehow in the moment can’t. Yet somehow those actions are imbued within the cigarette itself, the absent possibility making presence of that motion, the longest drag and the wistful exhale. Consciousness solidifies as embers and smoke: becomes thing; fully melds into the body even while remaining narratively somehow apart. The supplementary cigarette instates that split: even as smoking itself attempts a yielding, there is always a temporal logic of desirous cleaving. This is its process of transforming…the literal becomes figural—a frail, expendable ‘link between scenes’—the smoker dwindles in memory, stares into distance through a veil that is always there, then faintly dissipating…

The idea of melding with the body, melding bodies (O the erotics of skin-stuck ash), is compelling for smokers because there’s a sense that the cigarette becomes more than mere chemical extension. Like Derrida’s pharmakon, it’s both poison and cure: a release from the pain of nicotine deprivation, but also the poison that reinstates that dependence cycle within the blood. When smoking, you slip between worlds of the self, oscillate between freedom and need. All the old cigarette ads liked to tout smokers as self-ruling souls, lone wolves, Marlboro men who could conquer the world in the coolest solitude. The truth being really a crushing weakness: have you seen a smoker deprived of their vice? Tears and shivers abound, as if the body were really coming apart, the spirit melting. The cigarette becomes synecdochic mark for the smoker’s whole self. Think of Pulp’s ‘Anorexic Beauty’: ‘The girl / of my / nightmares / Brittle fingers / and thin cigarettes / so hard to tell apart’. Fingers and fags merge into one, when all that’s indulged is the un-substance of smoke.

I have certain friends who I could not imagine without their constant supply of paraphernalia; every interaction involves the punctuating rhythms of their trips outside, or desperate searches for lighters, filters, skins. I have seen them smoking far more times than I’ve seen them eating. The very nouns connote that sort of fleshly translucency; it’s a sense that these flakey tools really do mediate our experience of time, space and reality. There’s a horror in that, as well as a remarkable beauty. I have had many epiphanies, watching my friends smoke, the way they stylishly cross their knees or flip their hair out the way or cup their hands just so to protect that first and precious spark. There’s a sort of longing for that ease, that slinkiness; an ersatz naturalness of gesture which is itself a reiteration of every gesture that came before, the muscle memory of a million screenaging smokers always seeking that Marlon Brando original. The protagonist of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005), lusting after the way Robert De Niro so effortlessly sparks up a fag, as if each motion was the freshest, the purest expression. Authentic. The compulsive abyss of the Droste effect in advertising, mentioned by the young Sally Draper in mid-century advertising drama Mad Men: ‘When I think about forever I get upset. Like the Land O’Lakes butter has that Indian girl, sitting holding a box, and it has a picture of her on it, holding a box, with a picture of her holding a box. Have you ever noticed that?’. To smoke is to wallow in that loop-work of fractals, feeling each replicated gesture slip past in the artful skeins of the next.

10:04’s protagonist, Ben, observes his lover Alena smoking a post-coital cigarette: ‘“Oh come on,” I said, referring to her cumulative, impossible cool, and she snorted a little when she laughed, then coughed smoke, becoming real’. There’s an uncanny sense of removal in that: the notion that in playing character, channeling gesture, Alena becomes real. Observing her smoke, Ben is able to achieve a more sensitive awareness of his material surroundings, his attuning to nonhuman objects. He also feels as though the smoking transmits a particle effect that draws his and Alena’s being closer together, as if those tiny motes of poison were causing a mingling of auras, a certain transcendental longing nonetheless grounded in the physical: ‘We chatted for the length of her cigarette […] most of my consciousness still overwhelmed by her physical proximity, every atom belonging to her as well belonged to me, all senses fused into a general supersensitivity, crushed glass sparkling in the asphalt below’. The little chimes of assonance betray that sense of mutual infusion, which can only ever be fictive possibility, the poetic conjuring of words themselves. Later, after feeling the disappointment of Alena’s ‘detachment’ towards him, Ben sends her a fragmentary, contextless text: ‘“The little shower of embers”’. While he regrets sending it, it speaks of our human need to talk desire in material metaphor, often enacting the trailing effects of synecdoche. Here is my (s)ext.: my breasts, my cunt, my limbs. Extensions or reifications, lost signals or elliptical read receipts betraying aporia…We offer a glimpse then withdraw our being. What remains is that transitory passion he cannot let go of, while she so easily finds it extinguished in the sweep of her day.

For Ben, ‘the little shower of embers’ lingers. It’s difficult not to think of the street-lights again, the punctuating markers of spatial trajectory across the grid of the city, twinkling in millioning appearance on 10:04’s book cover. I’m reminded of the street-light ‘Star Posts’ in early Sonic the Hedgehog games (we used to call them lollipops—appropriately enough, another supplement for oral fixation) which you had to leap through to save your place, so that if you lost a life you’d revert back to that position in the level. They’d make a satisfying twanging sorta noise when you crossed them, and sometimes if you had enough rings the Star Posts could open a portal into the ‘Special Stage’. Even the virtual contains its checkpoints of place, the long thin symbols of presence not unlike those Silk Cuts, the I, the anorexic fingers. A sense of these moments that flicker, the length of the cigarette marked as physical duration and spatial decay. A Deleuzian fold or cleave in time. In the new Twin Peaks, Diane is an entity stretched across dimensions. No surprise that she smokes like a chimney, and every time someone tells her to stop she yells fuck you! The implication is a laceration, quite literal. There’s a violence to that delicious rip, the cellophane pulled off the packet. Then there’s episode 8, where the universal smoker’s code—Gotta light?—acquires the bone-splitting currency of horror in the crackling mouth of the Woodsman.

Associative moments lost in time:

She gave up drinking and started smoking on the long flat dirty beaches;

People who burned bright & were extinguished young;

A neighbour whose house smelt so badly of stale fags we used to play in the garden instead;

His fingers shivering like leaves;

The reciprocity of this loose tobacco;

Taste of aniseed skins from Amsterdam, watching the film version of Remainder;

Broody Knausgaard in The Paris Review, admitting his continual addictions;

Smoking on the steps of my old flat saying everything will be okay—but what?

To smoke is perhaps to enact a kind of haunting, owing to the ghostly flavour of the former self performing the same action over. A poststructuralist elliptical supplement or sincere act of nostalgia. Masculine desire for luminous females, or the complicated politics of vice versa. A strange deja vu which mingles identity’s presence with absence. The fictive act of smoke and mirrors. In Safe Mode (2017), Sam Riviere’s ambient novel, the recurring character James recalls a phantom encounter, shrouded in imagined memory:

One summer at a garden party I danced with a girl in a green dress. I remembered her from high school, and built afterwards in my mind a certain mythology around the events of the evening…I discovered the next day that she had died a few months earlier. It seems I had been dancing with her sister. Almost any encounter can alter its configuration through the addition of detail or, more traditionally, a death.

In Safe Mode, problems may be troubleshooted as the brain or hard-drive enters a twilight zone of reduced consciousness, minimised process. The addition of detail: supplemented ornaments of thought, the drapery of memory or retrospective chain of events. What shatters through desire is the gape of that absence. A similar thing happens in 10:04, as Ben recalls his younger self falling in love with a girl he erroneously took to be his friends’ daughter: ‘She became a present absence, the phantom I measured the actual against while taking bong hits with my roommate; I thought I saw her in passing cars, disappearing around corners, walking down a jetway at the airport’. Always at the corner of his vision, she becomes an elliptical presence, diminished to the dotdotdot of memory attempting to make the leap. I think of binary code, the stabbed insistence of typewriter keys. In actuality, nobody else remembers who she is. Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear. What essence lies beyond or within that phantom appearance? What real need is channelled in the flimsy aesthetics of a lit cigarette, a girl in a memorable dress? We fashion narratives to make reality…what is this deep mode of operation; in what state of mind may we dispel rogue software, the signifying virus of niggling, unwitting desires? What jade-coloured jealousy of movement spins like an inception pin, stirring its quiet tornado of dreamy amnesia? How do we pick up our lost selves without cigarettes, what Self calls the usual rebirth of the ‘fag-wielding phoenix’?.

The mysterious ennui of Francoise Sagan’s chain-smoking heroines will always haunt me. Don Draper in the inaugural episode of Mad Men, ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’, lingering over a Lucky Strike, will haunt me. Those moments of waiting for soulmates to finish cigarettes outside pubs will haunt me. Sitting by the sea on a picnic bench watching a friend smoke, talking of boys, will haunt me. The man who kept bugging us outside the 78 about ~The Truth~ will haunt me, even when I gave out a light to shut him up and tried to quote Keats—‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’—losing his features to the veil of smoke as I myself drowned in chiasmus. Every teenage menthol enjoyed in clandestine fashion, on long walks up the Maybole crossroads, will haunt me. My clumsy inability to roll will haunt me. The cigarettes of stolen time behind the gym block at school will haunt me. The erotic proximity of those curled-up flakes, the crystal possibility of an ashtray haunts me. Frank O’Hara’s cheeky smoker’s insouciance haunts me. The way you stroll into newsagents and sheepishly ask for the cheapest fags will haunt me. Those dioramas of gore on each new packet will haunt me. The foggy spirals of facts and platitudes, health warnings and reassurances haunt me. The way you light up to kill time will haunt me. The dirty, morning-after coat of the tongue still haunts me. My own slow longing for breath will haunt me, I’m sure, in some other dimension where I start smoking and finally find the special addiction. For now, I choke behind strangers, stowing old packs in neglected handbags, writing as supplement for the first delicious drunken fag. Without that fixed, poetic, smouldering duration—Bonetti’s ‘comma between phrases’—I’m meandering through sentences, essaying in mist, waiting as ever for the next scene to begin.

April, the sweetest candy of a pink-tinged sky blessing the late afternoon. Rebecca has sat in the garden for hours, watching the birds nibble from the feeder and splash around by the pond. This is her Grandpa’s garden, though he no longer enjoys it. They have him cooped upstairs on a dialysis machine, in a bedroom that smells of sweat and death. Rebecca is not allowed up there: the air, her mother says, is not fit for a young and blooming girl.

She misses her Grandpa. She remembers him mowing the lawn on Sunday afternoons, stooping with his bad back. She remembers him commending the shapes of his moon-faced daffodils. She remembers him singing Frank Sinatra in velvet baritone while pruning the roses.

The roses are now out of control. They cluster all over the flowerbeds along the path, dangling out with their swollen, sumptuous heads. They have grown so tall that they bend over, crippled with the excess weight, the stems stretching to breaking point. Grandpa would be so disappointed if he witnessed the state of his roses.

Sometimes, Rebecca liked to peel off a petal or two. It was hard to resist; once she took the first few, the others came off so easily and they just slid softly into her fingers. Vivid trails of pink and red petals are now strewn along the gravel path, where Rebecca has walked like a bridesmaid.

At the back of the garden is the apple orchard. In winter the trees are gnarled and bare silhouettes, and not a soul would dare enter the darkness between them. Now that spring has arrived they boast their pretty bows of white, flaky blossom. Every year, Grandpa used to send glossy photographs of the apple blossoms to Rebecca and her parents, who lived far away down in London and rarely made it up to visit. The sight of those lovely trees was always a dream to the young girl who yearned for the country.

“When can we go and see them for real?” Rebecca would sigh.

“Oh, sometime in summer. Maybe Christmas.” They were so often dismissive like this. They had waited too long to see him and now he was dying. Even Rebecca knew it.

She was growing quite bored now, in the garden with no-one to play with. She knew there would be supper soon: hot buttered crumpets with a dark smudge of Marmite melting inside them. Real Earl Grey (loose leaf) because that was the only tea Grandpa had in the cupboard. Rebecca thought it smelt a bit fusty, but you could read the tea leaves at the bottom of the cup afterwards. She thought she saw a bird in hers that morning.

Yes, she was quite bored. The hula hoop which she had brought up from London lay abandoned on the lawn. She had tossed away her tennis racket somewhere into a dense clump of shrubs, because it was no fun to play by yourself, hitting a ball against the shed wall. A bag of marbles had burst open on the patio, the little glass balls having long rolled away, to settle amongst their brethren of grass and gravel. Rebecca had no toys left and besides, she was so tired of them all.

Even the insects had bored her, with their slimy indifference to her existence, their urgent desire to escape her clasping girlish fingers. She couldn’t give a toss about snails and slugs, or even butterflies anymore.

It was in this moment of tedium that she spotted the boy through the hedge. She couldn’t believe she had never seen him before. It was a difficult thing not to be spotted, not to make a peep, but Rebecca crawled expertly into a gap and tried not to breathe as she watched him. He was lying on his front, kicking his long legs back and forth. From this angle, he looked about fourteen. His hair was sort of ginger but also sun-bleached, as if he had spent a long time outside in a streak of good weather that Rebecca must have missed. He looked like something the sun had offered as a blessing. She could see his freckles, the concentrated curl of his lips. He was drawing in a big sketchbook which was flipped open, so that sometimes the breeze rippled the pages. Rebecca felt her heart hum and flutter in the cage of her chest, like some swarm of insects had trapped itself deep within her. He was so beautiful.

She wanted to crawl right out of the hedge into the next-door garden, step into the other world where he existed. She wanted to talk to him, ask for his name. See what it was that he was drawing. She felt like the secrets of the world would unlock themselves once she had learned his name. The sapling of herself would unfurl and a bounty of happiness would overflow from her body like the golden leaves in autumn.

“Rebecca!” she froze. It was her mother calling. She had been searching all over the garden for her daughter and now here she was, discovered in the hawthorne with white blossoms caught in her hair and a strange smile on her lips. She saw there were tears in her mother’s eyes, clinging and spilling like rain from the knots of tree trunks. How could there be tears at a moment so pure, so lovely?

“It’s Gramps,” she gushed, “he’s, he’s gone!” And so her mother pulled her out of the hedge and clutched her in her arms, held her so tight Rebecca thought she would burst. It didn’t make sense: he’s gone, he’s gone. As her mother sobbed into her hair, she watched the apple blossoms being blown away by the gathering night wind. Next-door, the boy stretched out his long limbs, packed up his things and disappeared.

(This little story emerged out of a longer short story project combined with prompts from Glasgow Uni Creative Writing Society’s Flash Fiction February challenge (‘renewal’ & ‘orchard’)).

Afternoon passes the sky as an angel dying slowly on a bed of cloud.

I am awake as I am walking and wondering

where was winter until now?

***

A walk in the woods from Kirkmichael to Blairquhan

A walk to the monument at sunset

The village glittered with night-fallen frost

Christmas begins with a different ritual for everyone. For some people, it’s when the radio stations start playing familiar Christmas hits from the 80s. For others, it’s the first bite of a mince pie crumbling its buttery sticky sweetness in your fingers. For most supermarkets, it’s the day after Halloween, when the shelves are quickly stocked with tins of Roses and Quality Street and Celebrations and a Christmas tree is rather humbly erected in every store’s entrance. For me, it used to be when we started making cut-out paper snowflakes at school; when they would play Christmas songs on the old stereo system that crackled when anyone walked near it, as if it were possessed somehow. Or a trip to a pound shop to buy our dog an artfully tacky sparkly collar and/or chew toy and/or basket of treats. These days I’m involved in buying sparkly socks more than dog collars, but the sentiment is still there.

Some people are super keen for Christmas and have their trees up right from the first of December. In the library during exam period the festive jumpers are out in full swing, as are the seasonal lattes (Praline and Pumpkin Spice) retrieved from the Byres Road Starbucks. In our house, the tree usually doesn’t get put up until Christmas Eve; since our cousins from England would sometimes come up to us, we would wait for their arrival to decorate it, late in the evening, before leaving out a carrot, mince pie and brandy for Rudolph and Santa.

Traditions, however, change just like people. At school, Christmas came with the baggage of P.E. becoming training for social dancing throughout December. No Scottish child has been exempt from the painful awkwardness of having to choose a sweaty-palmed partner and learning to dance often incredibly complex steps (I’m looking at you, Strip the Willow) to the amusement of all their peers. And that’s if they’re lucky enough not to be left last and paired with a teacher. Of course, the older you get, the less embarrassment tends to dominate your entire consciousness, so dancing becomes more fun. You know, I would even go to a ceilidh of my own free will now, although back then I thought it was a form of torture cooked up to torment children out of enjoying their Christmas. It didn’t help that the school dance also involved the necessity of buying a compulsory sequined party dress (not a fun enterprise when you are a ten-year-old tomboy that hates shopping) and a dinner whose only option for vegetarians was salt and vinegar crisps (I swear I’m not really complaining). Still, the brutally hilarious fights over ‘he wiz dancin with ma girlfriend’ that you could witness outside afterwards while waiting to be picked up made the night somewhat worth it.

At secondary school, playing in the brass band forged new festive traditions. There were the rehearsal days for the Christmas concert, where you got to take a whole morning out of class, carrying your instrument down to the tinselled town hall and sit for hours munching snacks from the local Spar and watching everybody else perform. Then there were the primary school tours, where we would pile into a mini van and play in the surrounding school assemblies for the generous payment of a box of chocolates that were swiftly devoured before lunch. You felt so important, playing up there on a stage and being praised by your old teachers while all the little kids watched you with wide-eyed wonder and you remembered that you were in that crowd only a few years ago, hoping that someday you could be the big kid on stage with the shiny instrument adorned with tinsel.

When Glasgow’s shoppers’ wonderland, the aptly-named Silverburn, opened its doors, a new tradition was created. Picking me up after a hard day at college, Mum would drive me up to the shopping centre and we would do the last bits of our Christmas shopping. There’s a certain magic to the indoor consumer paradise, with all the lights and the giant snowglobe for kids to get pictures in and the seductive glow of expensive shop windows. Everything was warm and clean and once we’d done our shopping we’d go for a mince pie at Starbucks, where we could look out over all the people dressed in reindeer jumpers and laden with glossy shopping bags. These days, traditional Christmas has become more fashionable and you can go to see the Christmas markets in pretty much every British city. It all has a German and Scandinavian flavour which still feels a bit refreshing. We used to always go up to see the lights at George Square, a tradition that seems very sad and innocent now after yesterday’s heartbreaking incident, but nevertheless retains importance in my memory – and many people’s memories, I should imagine. There’s also the lovely, extravagant decor of traditional department stores which resonates the Christmas magic of the early twentieth century: I’m thinking Princes Mall and House of Fraser in Glasgow, then Jenners and Harvey Nichols in Edinburgh. I’m sure London too has much to offer, although sadly I only get to experience that through my half-hearted attempts to join my family in watching the terrible Christmas specials of Made in Chelsea.

It used to be that we’d go to Culzean to collect twigs and fir cones and sprigs of holly for decorating the house. We’d spray them with gold and dip them in glitter. Sometimes we still do that, as if living out the old ritual of making Christmas cards that Mum made us do every year when we were at primary school. I love crafting and firmly believe that it’s one of the most relaxing things you can do. A few years ago I went through a phase of making loads of candle holders out of glass jars which I painted with acrylics. At school there was always the last few days of term where people wandered about not doing much and hardly going to class. Teachers would wave us away with a ‘Merry Christmas’ instead of teaching us and we’d sit and watch Meet the Fockers on repeat (at least in primary school we had the enterprise to bring in board games) and wish we’d decided to skive. Often I retreated to the art department where we could make snowflakes and paint bottles and pretend we were little again.

At uni, the last classes are a bit more exciting. For one thing, mulled wine often factors in. Also, the fear (in first and second year at least) of Christmas exams. I used to hate how university decided to give us exams in December, with only a week to study for them. It was incredibly stressful, but in the long run I suppose it was a good thing because we didn’t have to study much over Christmas, as we did with the January prelims for Highers and Advanced Highers. Sometimes, the fear makes Christmas all the more sweeter. I remember in my first year at uni, I’d just gone with a friend to an impromptu gig at Brel on Ashton Lane. It was Rachel Sermanni and the singer from Admiral Fallow who were playing acoustic sets and it felt very wintry and magical. And when I left, to go back to my flat to cook chilli bean soup and study, it began to snow as I walked up Great George Street. It was one of those enchanting moments when you feel everything swell up and really seem to mean something. Like you’re in a movie. I was finally so happy to be in Glasgow and a student, even with three exams that week. It’s hard to not love your university and city when it looks like this:

After exams (and more recently, essay and dissertation hand-ins) comes all the comforting Christmas rituals that I love so well. Buying sparkly nail polish and the December edition of Vogue which weaves a fantasy of luxury office Christmas parties thats nowadays I have the (privilege?) of serving if not just imagining. Seeing fairy lights being put up in the restaurant where I work and all the Black Friday and Christmas bookings looming before us. Decorating the Christmas tree at home each year with new decorations got in our stockings. I missed out on decorating the Christmas tree at school, but came back from Belmont one day to see that we’d managed to procure one for the sixth year common room, and someone had decorated it artfully with ornaments worthy of any John Lewis special collection: a load of empty crisp packets.

Still, sometimes makeshift Christmasses can be fun, or at least interesting. My brother and friend Jack randomly phoning in and singing ‘Last Christmas’ live on BBC Asian Network radio. Stringing a half-hearted bit of tinsel and some Poundland fairy lights over my bookshelf. In first year at uni, we had a festive dinner party in halls, but seeing as I’ve always prioritised exams and studying over pretty much everything else, I ended up cooking my own vegetarian option which was incidentally the only thing I had in the fridge: a fried courgette. Even so, the party poopers (obviously I was included) were the ones who had to scrape all the meat scratchings and grease off the dirty pans like a band of Cinderellas until one in the morning while everyone else was having a good time at the QMU’s Cheesy Pop. Still, it was a lesson in the underside of hospitality…

Arguing about who will do the washing up is a regular feature of our household at Christmas, as it probably is pretty much everywhere. It’s not so bad when you do it together. That’s the festive spirit, anyway. Then on Boxing Day we tend to go for a nice long walk – one year it was along Ayr Beach and through Belleisle, another through Maidens and Culzean, in past years it will have been places in England. Christmas Day used to be an early dinner and then sitting in the hallway stuffing myself with Quality Street and playing the new Pokemon on my Game Boy Advance while everyone else watched the Queen’s Speech and boxsets of Only Fools and Horses. We still retain the tradition of eating bagels for breakfast (I wonder is this some kind of strange nod to our Jewish ancestry?), but nowadays it’s more a cheeky Amaretto or some Bucksfizz (maybe it should adapt and be Buckfast) and a lovely walk up to Maybole monument through the golf course and dinner at about eight when the crappy oven we have at home has finally decided to roast the parsnips. Both have their magic. The best part is still the waking up early to open my stocking. This year, I’ll be working Christmas Day, so I’ll have my Christmas on Boxing Day. But that’s okay, because Christmas is what you make it.