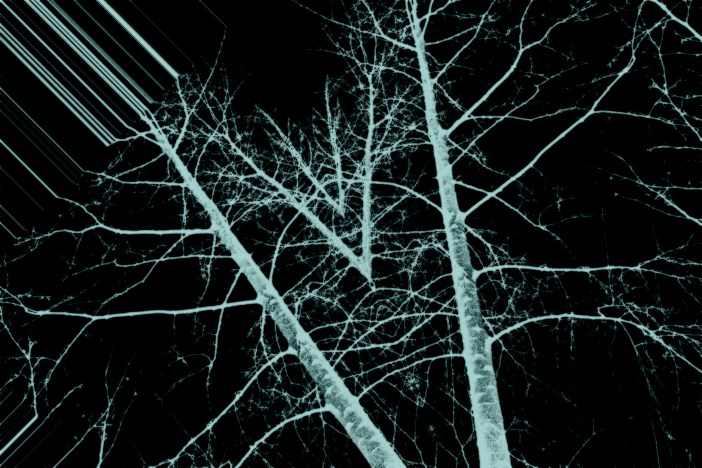

Sylvia Plath wrote many of her Ariel poems in the wee hours before dawn, sucking in the cold and inverse crepuscular air, its colourations of sinister lilac and absent sleep. We have a cliché of the poet’s spontaneous overflow, but instead with Plath there’s a sharp intake, a suspension of air, of breath: ‘Stasis in darkness. / Then the substanceless blue / Pour of tor and distances.’ We have to think through the impossibility of a substanceless blue, as everything must be a component of something; we are all of a sort as perilous hybrids, weak in some place with the viral code of our own demise, shimmering within and outside us like a beautiful aura. The speaker paralyses herself on the brink of sublime, of suicide. Tor: a hill or rocky peak. Vertiginous depths to erase the scale of the self on earth. Tor: a free software project which protects your privacy online. Where history bounces back, is the elaborate sarcophagus that traps the foul air of your history. Think of layering, onions, peeling stench of purple flesh. Indulgent recipes for regret; the cloying addresses of cheap pornography, of midnight Amazon deliveries. Inside the deep centre a secret, liquid sweet as Timothy Morton’s chilli-dark core of chocolate ecology. Chilli, chilly; a shiver in the air that is freeze or fiery. I have been googling your name in my sleep. A shivering, unsettled enmeshment. The encryption an insufficient addition to the substance of memory, its thick brain mulch of skin and image. Such protocol stacks are hypothetical only, nested as the heavenly day that will not die. Wordsworth singles his day from a tangle of others, the onion clot and rot of forgettable hours. To dwell forever in that substanceless blue! To wear innocence on the sleeve of freedom! Plath’s line breaks are harsh and sharp, they flake off the page in their skinly abscission of sound and sense; the body is imposed on grander scales, made to stretch then wither in variable ‘dead stringencies’. All of a space, the thin poem shivering down a spacious page. All of this is so much of air. Take me to the edge, go on, it’s a dare.

An understudy is someone who learns another’s role in order to act at short notice in the person’s absence. You lurk in the background, an absent presence of possible flourishing. The poem as understudy: recipes perhaps in the absence of breathing. What we read when there is no air left to breathe. Poems in reserve for a gradual apocalypse. What exists as core substance, what complements the element whose insouciance charms the lungs without thought. Derrida’s maddening supplement: neither presence or absence, something added and something in place of. An understudy for air, a rehearsal of air’s function. Anthropocenic, tarry air, stung with coal and thickly textured.

Robert Macfarlane asks that we find a ‘thick speech’ for articulating life in the time of climate crisis. Enter Daisy Lafarge’s Understudies for Air (Sad Press, 2017). This is not a collection, ostensibly, about ecology or even the end of the world. It is a phantasmic scaffolding of words and lines for living, breathing, being. Its epigraph takes the axiom of the pre-Socratic philosopher, Anaximenes: ‘The source of all things is air.’ Air being then the ubiquitous neutral substance, something available for occasional roles in physical process. A reluctant but capable actant, developing itself or forced upon by other natural causes. Air’s principle shifts bring about the other main elements: flicker into fire through precious density, condense into wind or water, earth then stone. Anaximenes articulates this through a simple example: if you relax your mouth and blow on your hand, it’s hot; if you do so with pursed lips, the air is cold. So rarity correlates with heat, density with cold. A beautiful, quiet, material intimacy. Everyday action, for Anaximenes, here forms the source of a theory of matter, and yet ever with time this matter recedes. There’s a scarcity of air, something sparse and grasped for in the gelatinous enjambment of Lafarge’s lines.

Precision of form: shortness of breath. When we pause at caesura, pause to breathe, when we lilt our words over the ambiguous interval of a line-break, we are forced temporarily to think about air. I recall the little ticks my brass instructor would make on a sheet of music: remember to breathe. The ticks would supplement a conventional musical pause; I guess I just needed more time to breathe. Breathing is temporal, but also material. There’s a precision to Lafarge’s form, a negotiation of reflective lyric transposed through material effects and affects. In ‘sapling air’, a sense of childhood’s loss is articulated as nonhuman ailment, the ‘first outbreak’ which is a poisoning of the air or the bark of trees. At first I think ash dieback, but then we are taken somewhere more grandiose, planetary, magmatic. Lying in the liminal space between ‘child / and whatever came next’, the speaker is in the bath, ‘gazing up through the skylight / as a plane passed overhead’. This sense of temporary epic scale, its vanishing écriture of ‘vapour trail’, is a writing of fleeting sheen. I think of glassels: those stones which appear glossy beneath water (in river or sea) but when picked and brought home they revert to dispirited dullness. It is as if life has left them, where momentary they truly appeared as vibrant matter, appealing to the senses with electric connection. Is this the fate of the bath-varnished body? How beauty consists in the wounded part of a thing, a fragile glitch in the viral code—what makes death inevitable. Stones ground down by the sweat and chafe of salty water, the sky a landfill for carbon dreams, modernity streaked across substanceless blue.

The speaker glimpses the oscillating scales of panorama and miniature: the passing plane and the ‘passengers’ eyes’. She sees through the eyes of others; a vertiginous, fleeting sublime in which she is the one looking down and the one looked down upon. Humans become binary nodes in this networked communion of sound and sense: ‘the passengers’ eyes flickered on and off / with signal’. Air carries, air travels. Air miles, as both temporal noun and verb. I find myself tangled in the space between transitive/intransitive. Air signifies the dialectic flickers of presence/absence. Accumulates, billows. What the speaker notices is a peculiar distortion, a toxicity overlaid with her own poisoned body: ‘I looked down. the bath water / was the colour of porphyry and I could no longer breathe’. The excess of the skin flakes away as feldspar, silicate rich and igneous, carrying traces of radial or volcanic exposure, imperial purple or deposited copper. Containing within it divergent scales: wee matrix crystals and larger phenocrysts. The speaker experiences her body as this suddenly alien thing; the sight of the bathwater steals her breath. Is it the first glimpse of what the outside does to the inside, the staining within us we leave on the world in a permanent toxic chiasmus? But I can’t help think also of period blood, given the speaker’s interlude adolescence: something tricky to articulate that nonetheless clots in the mind as childhood’s instated loss of innocence, a condensation of excitement that clings then turns readily and stickily to red, to blood. That moves in turns, cycles as the waxing mist of the moon. What is this substance, this iron-rich bodily flood? Where matter confuses, we turn back to air.

She tries to express to her father a bewildered grief, ‘there’s something wrong with the air’, but her ‘words went through to dial tone’. There’s a delay, language meeting its buffer at difference: through what? Gender, generation, divergent points of vision? Her special melancholy is something that lingers down the line, seeps inside the passage of time. The poem closes: ‘I still wonder, how many months, years from now / he will listen to the message’. Throughout Understudies for Air, Lafarge uses this technique of unfurling: instead of saying simply, ‘how many years from now’, she adds in the months, practices a sort of delay or lag. I think of smoke billows, slowly dissipating. Of what it means to say, there was chemistry between us, an atmosphere in the room. The way voiced words vibrate momentarily in meaning then once again settle to silence, stasis. An almost electricity, crackling then out. Compare this to the written word’s more permanent, inevitable viscosity. Language sticks: you can tease it over and over, read the same thing till centuries down the line the ink wears off from the page. You can replicate. Speech is quite a bit more fleeting, unless you set it down on wax or tape, find new ways to materialise language’s spit, crackle, lilt. The forcing of sign and shape from sound.

Air in Lafarge’s collection is a sort of pharmakon, in Jacques Derrida’s sense of an undecidable fluctuation between poison and cure. It is a substance acted upon with the medical impetus of invasion: in ‘desecration air’, ‘brittle waves of grit’ are ‘growing, syringe-like / into the air, and in so doing suckle / and cleave the dunes around them’. There’s a sense of maternal genesis and geologic violence, an injection of force into air’s spaciousness. For air at once signifies space and density of matter at the brink of scattering, sparking, forging. I start typing what is air into my search bar and it suggests, where can it be found? I am suddenly struck by air’s mystery, the possibility of everyday deception as to its ‘nature’. What is taken for granted has elusive substance; after all, can we view air in the object-oriented sense of ‘object’, or even, at transcendently nonhuman scale, ‘hyperobject’? For air blends and bleeds, both substance and accident. The painting or glass had an airy quality, we talk of a room as light and airy. Does this mean more air, or air less dense, more receptive to breath and space and quiet? Air is rich with the silt of existence: dust being its materialised twin, these myriad phantasms of hair, fibre, textiles, minerals, meteorites, mostly skin. Air is nitrogen, oxygen, argon, carbon dioxide flavoured with traces of neon, methane, helium. We breathe air but also pass constantly through it, as our molecules swim in the vast bombardment of other molecules swirling. Ambient air is safe, we pass through it daily; but air can also spark, as fire’s immanent ingredient, awaiting some flagrant chance to burn. We talk of dry air, damp air, air that feels ‘close’. Air signifies both absence (space) and presence (elemental matter, tangible substance). Air is always potentially transformative.

There is a poem called ‘calque air’. Calque means loan translation: a word-for-word exchange of meaning across languages (examples include ‘fleamarket’ and ‘skyscraper’). In French it means literally ‘copy’, derived from calquer: to copy, base on, trace; derived again from Latin calcāre, to tread, press down. Thus in the abstracted xerox of translinguistic exchange, we meet a sense of material rubbing, the friction that exacts its inscription between two substances: stone on stone, wood on wood, paper on paper etched with lead. It’s a physicality that chills the spine. Yet tracing somehow also connotes residue, the excess material produced by this rubbing, the patterning stains set down by a tread, like footprints sunk deep in the sand and preserved semi-permanent by glitters of frost. Lafarge writes: ‘people / were finding messages / in their bodies they hadn’t / written’. Again this sense of material semaphore, whose translation is a phenomenological act of physical reality, a sudden otherness within us that requires an empathy, an excess, a confusion of words rubbing wrongly against one another: ‘it was decided the system was malapropic’. Language spiralling as if in the hands of the nonhuman, the air or machine or book.

Anthropomorphism reaches its textual extreme: ‘the book grew hair, organs, toes’, and so even ‘accurate translations’ become disputed, subjective, active and physical. What is it about air that somehow substantiates the symbiosis of language and matter, its aching and perilous leak? Here we are, tipped in the gaslit eve of twilight, where ‘the sky throbbed / sideways like a haemorrhage’. Matter acts upon us, causing a gulping or gaping as we churn through it, our bodies mucilaginous mulched into altered form, new affect. We can try to discern the nature of air, but in some way its inner essence remains recalcitrant, resistant to the interpretive instruments of other forms, including humans. Lafarge plays on the semiotic plurality of ‘forms’, poking fun at science’s ‘consent and feedback forms’, ethical necessities which prove useless upon the elusive air. This raises the question of how to extend a nonhuman ethics, what forms of consent are required when probing and monitoring their patterns of agency or behaviour? In ‘attempted diagnosis air’, Lafarge concludes: ‘in the end, / you left the forms in the airing cupboard / to let the air fill out itself; it acquiesced / in many hands of mould, dust and heat, / none of which you could hope to translate’. The air transmogrifies into purely itself, is available only as sensation in the perceptive ‘hands’ of other substances. It’s worth quoting Jane Bennett at length here:

Thing-power materialism figures materiality as a protean flow of matter-energy and figures the thing as a relatively composed form of that flow. It hazards an account of materiality even though materiality is both too alien and too close for humans to see clearly. It seeks to promote acknowledgment, respect, and sometimes fear of the materiality of the thing and to articulate ways in which human being and thinghood overlap. It emphasises those occasions in ordinary life when the us and the it slipslide into each other, for one moral of this materialist tale is that we are also nonhuman and that things too are vital players in the world.

Air is surely the channel for thinking through this vibrant materiality. Lafarge’s poetics, shifting through sparsity and density, perform this slippage between human and nonhuman at variable scales. Rooted in ordinary life, in personal memory, the poems of Understudies for Air root out these collected knots of ontological ‘torsion’, the ‘bunioned’ meanings that wash up like offerings then shut down all visible meaning—‘they closed in my hand / like eyes’. The lack of capitalised titles renders the poems’ drift into one another, in free-flow without the arche conventions of literary closure, of textual finality. A sense of fractured or wounded text, poems chipped out of a grander object, left now to change and drift. In ‘driftwood air’, driftwood makes a temporary semiology of the shore. Driftwood being perhaps the airiest form of wood, a text well-chewed by aquatic bacteria, lightened and smoothed by the tide; erosion performing its nonhuman act of calque: a copying of wave upon wood, the tiny treads of millioning microscopic appetites, like the imperfect press of a nonhuman telegram. With her spells of air, Lafarge conjures a vibrant ecology of non-anthropocentric process; evocative still as such effects take place through the decomposition of the lyric ‘I’, whose voice drifts out in nonhuman confusions, signals and distance. Human affect returns in glimpses like delicious flotsam, jetsam, moments of reflection gleaned from material debris.

The ‘I’ often shrinks or recedes, but sometimes floats over the ambient scene with declarative assertion: ‘the twin lines of naming and being / run parallel but never touch’. Such philosophic pronouncements then melt away in exploratory thought, lines closely attuned to trans-species process: the swell and lurch and pleat of water, plant, lichen or toxin. Once again we come to air as pharmakon, and so its process arises as a sort of pleasing monstrosity. The odd thing about plants is they just grow, often without purpose, foregoing teleology for an impersonal, gorgeous flourishing. In ‘asbestos air’, the speaker marvels:

lichen and moss

grooming your body;

it is a relief to watch

things grow without

difficulty

End-stopped punctuation is often foregone for free-flowing, morphological enjambment throughout Understudies for Air, so the inclusion of semicolon here is its own kind of force. I think of imagism’s stop-motion visual equivalencies: Pound’s apparitional faces in the metro and wet black petals. The ‘body’ in question could be human or nonhuman. There is a plain admiration of process and flow, the ease of growth that feels significant against the endless stuttering, knotted bolts of human maturity. And what about ‘asbestos’? More silicate minerals invading the air, released by abrasion and enacting a slow-release of symptoms, as deadly fibres clot in the lungs. Asbestos makes its own mark upon air. The speaker clearly craves that insulation, a felting of absence with ‘lichen and moss’ that comes as a ‘grooming’. Grooming being the softening and smoothing of matter, but also tinged with danger: to be groomed is to be seduced towards some form of invasive peril. Twin signals, twin materials; a chiasmus of death and sleep’s electricity. Sucking in air, we sleep towards death; slowly we rove over lines that enamour with deceptive simplicity. We can’t help but breathe in sleep; it’s just evolution. What’s more, nature isn’t mere positive growth, but might be compounded poison, cancerous swells. Tumours accumulating almost mycologically, darkly twisting and rising in the shadowy mulch of the organs, the undergrowth. Behind a benign appearance is the spectre of asbestos; for of course mosses and lichens are indicator species, material harbingers of polluted air. Air is the cure, the restorative; but air can also kill. It is both oxygen and carbon monoxide, its healthiness hinges on a delicate balance.

Air’s undecidability, perhaps, is a deconstructive motion of question and answer, a maddening circuitry of frazzled nerves and linguistic synapses. In Lafarge’s attempt to materialise air, to verbalise its form as supplementary poetics, writing does the work of metaphysics. Enter Maria-Daniella Dick and Julian Wolfreys in The Derrida Wordbook, glossing Derrida’s term undecidability:

If metaphysics teaches us how to read, and reading teaches us metaphysics, birthing each other in a twin maiuetics, then deconstruction also calls us to a reading. To read undecidability is to resist that other resistance which would efface it.

Air’s invisible toxins make themselves known with prickling, painful insistence at the miniature level of surface pollutants, scum left on water or stains on metal. A poet’s Keatsian eye would draw out this material tread of Anthropocene effect, illumine its slow evolution with the linguistic wit of a chemist. The irony of deep-time causation at the hands of humans, those obfuscations of cause and effect that place humankind as geologic agents. Reality, matter, climate change become undecidable. We are being taught, in these poems, the call to the earth that is really a subtle conversation within our own bodies—palimpsests of dangerous nature we tried to fashion but grew otherwise, anyway. Despite melting icecaps, the air grows colder in winter, it thickens.

Lafarge develops this viscous, hyperobjective symbiosis through her descriptions of air’s sticky contaminations. There are ornaments of scattered matter: bitumen, seed heads, the wildfire possibilities of ‘drying leaves’. There is a constant overlay of the biological, spatial and arboreal: ‘we soiled our mouths to mimic / the good fettle of root and seed’; those ‘dark thickets of lung’. I think of the word forest, then ‘for rest’. Places we go to shelter, to cleanse ourselves scented on pinewood air. We can’t see the woods for the trees, or was it the trees for the woods? Morton’s idea that we need a return to parts over wholes, this notion of subscendence: the whole is always less than the sum of its parts. A tree more important than a forest. Lafarge strains her ear to every little activity, the expressions of suffering that come from sources beyond the human: ‘on every corner a tree / articulates its script’. Tree language is material too, it is sound in the air unique, and seedlings glistering on rustling rhythms. It is the flail and droop of branches diseased, stung acid by rain or ravaged by leaking methane.

To put words in air implies a sense of declaring, but this is less the enlightened ejaculations of a singular genius and more a sensual symbiosis: ‘the words / identified me as carrier / and now along I go / sowing their imprint in air’. To sow, to plant seed, to let meaning take root and feed upon air and soil, sound and shape. By tuning to nonhuman forms of inscription, Lafarge attempts to answer the call of the absolute other. This is ecological poetry’s luminous tool, its potential ethics.

This is also, to a degree, Michael Marder’s ‘plant-thinking’: a thinking about plants, a thinking through plants, a symbiosis of human and vegetal thought at the level of form and content. Not discursive domination of subject but a perceptive, non-anthropocentric and multisensory modality of what Marder calls ‘transfigured thinking’. I cannot help think of a shadowy, cooperative alchemy in which the baroque foliage of language ravels round the utterances of the absolute other, those bladed shivers and flashes of light, that speak of time felt close in the skin of a cell. It is a metaphysical elixir that deconstructs its own postulated recipe. Metaphysics, for Marder, is unable to think coextensively ‘with the variegated acts of living’ that exist in plants; it seems to ‘affirm the quasi-divine life of the mind’, but actually ‘wields the power of negativity and death’. It risks becoming ‘a cancerous growth’, smothering the plants it attempts to draw ‘vitality’ from in knowledge and energy. I think of the chemical kill that Keats in Lamia implies is the effect of philosophy, which ‘will clip an angel’s wings / Conquer all mysteries by rule and line / Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine’. Writing poetically, we must be tender, channel the lurid sounds that fill the sparkling air, nevertheless deathly polluted as a charnel ground. Embrace inexplicable oscillations between the living and dead; challenge binary conceptions of stasis and liveliness, animals and matter. Retrieve a kindred sense of mutual mystery, preserve the lingering aura of species-being. Plant-thinking must instead be ‘receptive’ to the ‘pole of darkness’ within botanical existence. There is a Keatsian sense of negative capability here, a chameleon dwelling in the infinite and multiple, the rhizomatic offshoots of unknown effects, undecidability. There’s a Deleuzo-Guattarian intermezzo too, as Marder puts it: ‘To live and to think in and from the middle, like a plant partaking of light and darkness, is not to be confined to the dialectical twilight […]. It is, rather, to refashion oneself […] into a bridge between divergent elements’, to allow that darkness to shine as much as the light of visible knowledge. Remain discursively flexible, morph through variant perspectives.

We have here an immersive rhizomatics, hinting also towards Graham Harman’s assertion of the object’s metaphysical withdrawal. Lafarge’s speaker certainly stands in this middle, exploring ‘a vernacular for pipelines, / circuitry, the fetid grids and systems’. She doesn’t penetrate essences. Stinking like soil mulch, our carbon economy is overlain with what we traditionally take to be ‘nature’: those lichens, mosses, leaves. We are reminded that cancerous growths, chemicals and shameful asbestos are as earthly as the daffodil or ash tree; each to each, irrevocably and intimately enmeshed, from the clinging of air to shared DNA. The speaker lets nonhuman forms speak through her: the shape of those gusts and shudders, those incremental growths and sudden ruptures, take effect in the passage of language. She brings us quietly, unassumingly, to aporetic conclusions, refusing to clasp meaning’s assertion from the lateral sprawl, preferring the precarious, seductive dissolve towards undecidability: ‘I still think of them, their clod eyes / roiled with fever, churning the peat / of a stagnant loop’. Clod: insensitive fool or chunk of mass. A clod of stone, an ignorant clod. An estrangement of nature, a closure of humanity to uncanny matter, churned in the loop of signature tautology—a metaphysics of presence that is ever an ‘argument’, a stagnant pool. How we must dwell, thickly, in these poems, these fleshy pools of blood and sap and dripping air. The declarative trochee like a stone thrown in a pond, ‘roiled with fever’; these shivers on the petrified skin with its fur of moss, toxin, mould. Conveyers of nonhuman temporality. The speaker licks such substances with lapidary language; the effects are circling, strange, recursive as a maddening philosophical problem. She dwells quite certain in uncertainty. Perhaps this makes her the perfect understudy, questioning but never at the point of egotistical revolt.

If all that is solid melts into air, then we know this now to entail less evaporation than transmutation. Solid objects arise elsewhere. What daily we flush, cough and excoriate from our bodies floats out in the hothouse biosphere, only to be reborn as fragrant waste, the fettered matter that is fetid at the point of being/becoming other. In the pamphlet’s final poem, the speaker passes a ‘high-rise’ and in the shrill of its alarm encounters an ‘elderly lady’, naked in her white towel like a terrible angel wrenched from the heavens to corrode on earth. The white signifies a kind of surrender to time and matter; the woman addresses the speaker thus: ‘one day I will know how it feels / to haul around a body of rotten flowers, to let memory / chew holes in my mind like maggots’. I’m reminded of a passage from Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, where Peter Walsh witnesses a vagrant woman, ‘opposite Regent’s Park Tube station’, her gurgling vowels speaking in a tongue he cannot understand. Is this a primitive ecofeminist figure from the future-past, her voice ‘bubbling up without direction, vigour, beginning or end, running weakly and shrilly and with an absence of all human meaning’? She speaks with ‘the voice of an ancient spring spouting from the earth’, channels somehow that geologic core, its rupturing pain. There’s Jonathan Bate’s insistence on poetry as ecological dwelling, in The Song of the Earth (2000). Woolf’s eerie, primeval wanderer stirs up the dead leaves from their settled grave, recalls an ancient song that aligns feminine suffering with planetary pain. I think again of Lafarge’s speaker, lying in the bath with a sense of her own body eking out a substance unfamiliar, the water stained a curious, feldspar colour. Poetry as monstrous giving-birth, poetry as vegetal thinking; poetry as lichenous growth or ambient eddy and flow.

There isn’t much pastoral about Understudies for Air, where things are scorched or ‘unspeakable’, full of porous holes and an inexplicable, surveilling gaze, those eyes which absorb and emit reality with cytoplasmic osmosis. There’s a dwelling in-between; a refusal of pastoral’s smoothed surface, its crudely soldered contradictions. Lafarge’s material history is thick, polluted, complex: irrevocably enmeshed with the speaker’s autobiography, a slow enclosure of tainted expiration; the result of some unreachable, originary trauma—the first infected inhalation. As the first poem opens: ‘difficult to pin the beginning / of the bad air’. In the Anthropocene, as with shame and trauma, it’s tricky to find causes, to trace singular beginnings. We have to face the impossibility of the transcendental signified, keep crossing over the same old tracks, tuning to peculiar scale effects in the dust and dirt, shaking the rain from our wilting manes, blades, branches, names. We can hack at the data, break the trees. In the end it is all just mutual suffering, the poem as supplement for what we can’t say, the horror of thought that is personal guilt and environmental blame. Yet somehow, Lafarge stirs sweetness from the wastelands of contamination, a little bit of the old Eliotic ‘breeding / lilacs out of the dead land’, or Morton’s molten, dark ecological chocolate. We move from depression to mystery to empathetic, mouth-melting sweetness. What you bury might come up lavender later; death still tainting, beautifully, the fullness of life. There is a shivering ethical suspension between the one and the other, cheating human text with the infiltrating voice of the strange stranger, where even the poet doubles back on herself, shrinks and fades, becomes alien against her own voice and song. Amidst all these ‘unspeakable things’, Lafarge reflects the coruscating absence, the flicker-to-effect of the dust in the air; motes of melancholy love, life and death, that cluster temporarily in poems and feel like a homecoming, yet always on the brink of becoming unsettled. Forever this ‘speech / impaired through contact / with the air’, the wrenching of justice from staunch aporia.

All this is so much of air. The words clot and float, they are pushed elsewhere as stacks of data, the coded reverie of software forgotten. Dwell in the dark web, a gossamer poetics that drips with the fringe-work of hackers, pirates, spiders. Once again: ‘homes / for unspeakable things’. Protection of privacy, pelt of fur, air that gluts on the temporary flesh of speech. A child’s ‘moonmilk / crusted round its mouth’. Language for future generations, raised on the logic of ‘selenography’; all human attempt to make sense of time beyond the body. There is a rhythm and a dwelling, a child’s bright cry in mica-flecked darkness. We all find overlays for our love or trauma—‘perhaps it was an early leak of the air / that conjured the image of his mother’—but instead of burial there is only entanglement, the sentencing ever excess of ‘a bad root / growing in every direction’. Trouble is, we can’t find it exactly; it grows and grows regardless. It shrouds us, auroral, auratic. Lafarge picks at flakes of flesh and star and paint, travels arterial between filament, taproot, wire, synapse and galaxy. Understudies for Air feels performative, a traversal of myriad sorts that folds back on itself, reflectively prone to spiralling dialogue, a postured void. For, as Steven Connor reminds us, the thing about air is ‘it encompasses its own negation […]. Take away the air, and the empty space you have left still seems to retain most of the qualities of air’. It’s in this multivariant, phenomenological pulse that Lafarge’s speaker dwells, sparked against the air’s vibrant matter as much as its ever conditional abyss. I read her words over and over, fragments of collected matter; conjuring in the cold winter light some other possible, nonhuman chorus. I’ll vapourise now, leave you trailing in the ‘fuzzy, fizzy logic of volumes rather than outlines’ (Connor), for it’s the sheer glut of language, coming in and out of phase with human perception and nonhuman form, that really matters. Matters. Connor again: ‘We earthlings, we one-foot-in-the-grave air-traffic-controllers, may have much to learn from the clamorous cooccupancies the air affords.’