from Alice Notley, The Descent of Alette (1992)

from Alice Notley, The Descent of Alette (1992)

Wet-leaved, walking up hills with chain oil on my elbows, knuckles, knees. We are on the eve of the ‘big climate conference’, which is to say, to be a host city of preemptive closure: there will be no more roads so that nobody can block the roads without authority, no more bridges for your tiny feet. I imagine a commute that takes me north to Kirkintilloch and back along the canal, an extra hour and a half of leg power and stamina and to arrive like of a beetroot complexion to the moment when somebody speaks. These streets are mostly broken glassed, and I see nothing to sweep that; I see buildings go up, see extravagant plant life grow from abandoned houses. I dream about bike punctures from enormous shards of glass. A mushroom sprouts in the brutalist building. I should have planned to do something. More tired than words can.

Imagine awaking beautifully at 5am each day, to actual birdsong and car sounds, still going through the night to Edinburgh or the general east as they do. I miss the ocean, which I have not seen since May. Sometimes I forget that its quiet, rhythmic hush is always in my ears, a tinnitus with the switcher dimmed. All summer I swapped the ocean for industrial estates, teeming with buddleia. If I go to a club, it gets full bright. The hush. At 6am I make atomic coffee, await words, say rain. I could tell you about the new university building and how I will never find a space to work there, doomed to circle identikit floors like airports in a suspended time that nonetheless eats into my time of work, a starship, doomed to fill a cup of hot water and carry it up and down escalators only to be cast back outside with scalded hands, cried into blustering autumn. A hazmat suit to be a student, studying the microparticles of your love in blunder. If I could study on the floor, in the street, with the leaves stuck to me. But I am a sufferer of frostbite and poor circulation, owing to damp homes, an unfortunate experience in the snow and damaged nerves, fragile metabolism. I am not there anymore, in the place we have been

Canned words taste better with more salt on them. Fuck you. Sitting on the curb in the 1990s surprised us when a plane went by, it was carrying my childhood. Remember we used to put each other literally in bins, until that wasp stung your ass and I was sorry. We prise open tins for the juicy bits of the story like, what would it take to get the attention of a virulent benefactor? Should you become a red squirrel enthusiast, or take up the statuesque hobbies of sportsmen? What beneficent largesse would require it?

Imagine not living by the anticipatory hormone storm of a coming menstruation, or like, the cramping wildness of the night and morning or blood gushed trying to have coherent thought in the day when your mind is fog. I want to transcribe some of that fog to writing, to remember how it was when again I am in clearing, to be like this is the place, it’s never gone. I was held in it, the tearing itself to shreds sensation to write this at six in the morning before work. Plants don’t have to go through this; is it that they’re always ‘working’? How do trees feel when they shed their leaves? Is it like an annual period and do they miss them? Should I develop fondness for shreds of blood in the toilet, abject bits of me and not? I saw a leaf blush out of my mouth and into a leaflet. Smoking kills. I watch the men in high-vis sweep up the dead leaves, more like dying, into black bags by the side of the road. Someone around here is always burning rubber tyres in secret. It’s kind of erotic to watch people do something repetitive and with great concentration, as if no one else could possibly notice this. To do your work that way. O your beautiful butterfly shoulders. Missed opportunities.

For instance, I could have lived through this moment to learn another language, write a curriculum vitae for the purposes of waged employment, called you.

“It feels so good to walk in nature.”

Blood drop in the shape of sycamore.

Where is Canada?

The revenge fantasy is only that trees are flirtatious as hell, winking pollen so that you watery-eyed have to look up at the stars sometimes and beg, like take me. Let me out of the forest so I might see

(fantasies of committee,

the ground to tie

my own laces in figures of eights.)

Authenticity!

The figure of eight in Karla Black’s sculpture which is pink-smeared recalling everything I used to put on my face. The idea is to find a sort of peace with it. School bathrooms where a face was pressed against glass and cruelly examined. I dream of rooms filled entirely with blizzards of eighties-blue eyeshadow. Angel Olsen, 2014, Pitchfork Festival. Having lived with the spirit not for resale, traded on a stark memory of that colour where every remembrance seems to intensify blue, until all I have is the pigment itself, ultramarined into oblivion. To wake into that blue and not see beyond it. I put my sore arm through the right-hand loop of the eight and pulled this out for you.

In the dream we pass an armed convoy and into the bakery with coins allotted to us by authority figures, and we buy pastries adorned by sugar ice drawn in mobius curlicues, and the pastries flake away as we eat them, greedily on the street, so many flakes falling before the guards. And we are butter-mouthed in the face of conflict, war and summit. A kind of shout chokes the air but the golden morning goes on, the falling leaves. I have these cramps and double over in the falling leaves. Men come to sweep around me, where I have fallen. One of them bends down — he is so young to be working — and pats my head tenderly and I see a leaf fall behind him and I know that leaf to be us, so we embrace platonically for one moment, as though I were his long-lost twin, before the foreman calls his name, which I can’t recall—

No, not that at all — he touches the soft part of my ear, goes “are you not young to be leaving?”

In trash, the language of trash, the trash piled up against the highway of your declaration. The men stopped coming.

Azalea, camilla, plum blossom, hydrangea.

Rizla, tin foil, styrofoam, gum.

The noise of vehicles pulling up around the city, emitting fumes.

The petals shed and I sleep on them, dreaming my blue becomes turquoise

another morning where the sun won’t rise

until we are paid.

~

Painted Shrines, Woods – Gone

Au Revoir Simone – Stay Golden

Uffie – Cool

Margo Guryan – Something’s Wrong with the Morning

Green-House – Soft Meadow

Frankie Cosmos – Slide

Arthur Russell – A Little Lost

Grizzly Bear – Deep Sea Diver

Tricky – Makes Me Wanna Die

The Raveonettes – I Wanna Be Adored

Beach Fossils – Sleep Apnea

Lykke Li – I Never Learn

Cate Le Bon – Running Away

Vagabon, Courtney Barnett – Reason to Believe

Angel Olsen – Some things cosmic

Jason Molina – I’ll Be Here in the Morning

Cat Power – I Found A Reason

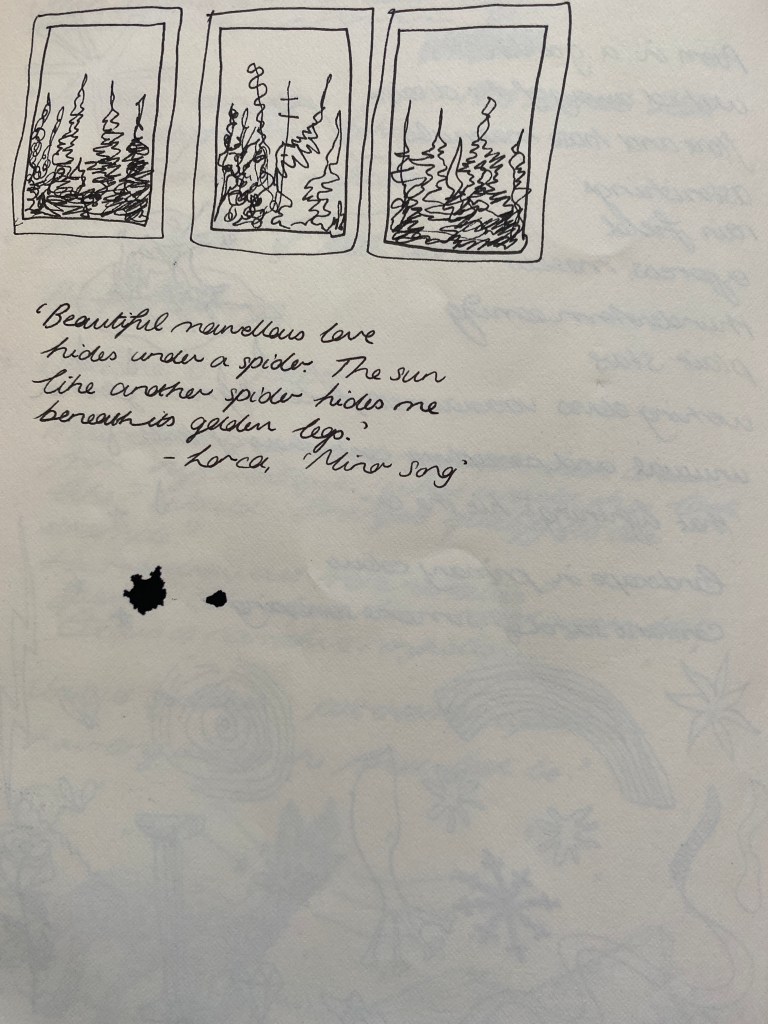

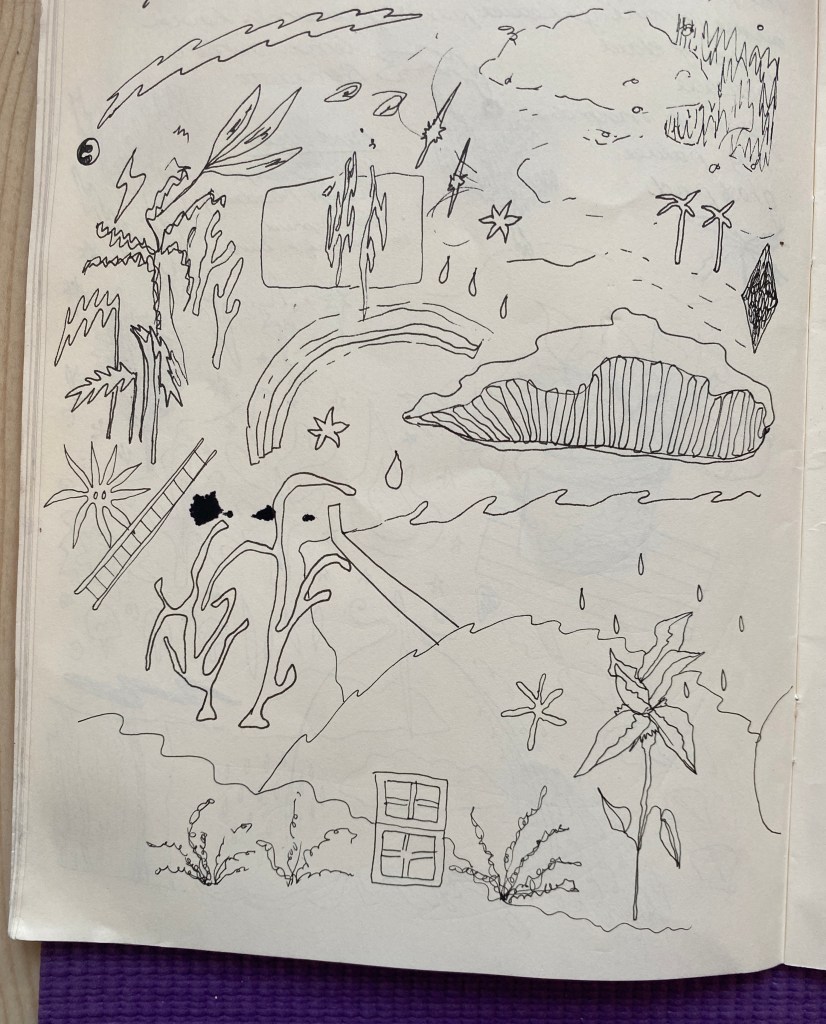

Some pages from a notebook kept while invigilating The Palace of Humming Trees (French Street Studios, 2021) during a thunderstorm in August.

Excited to announce a collaborative exhibition with artist Jack O’Flynn and curator Katie O’Grady, happening until 8th August at French Street Studios in Glasgow.

~

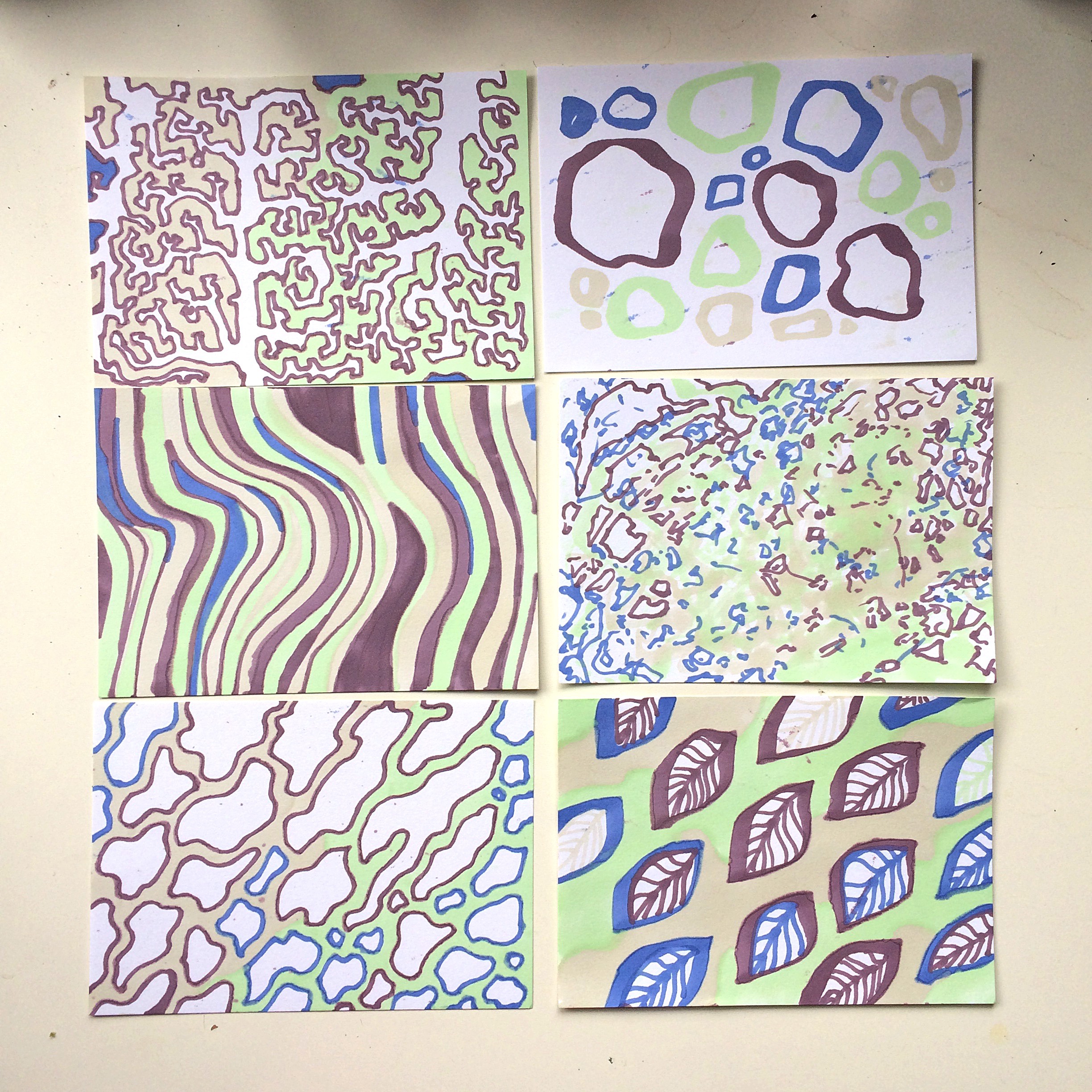

The Palace of Humming Trees is a collaborative project between artist Jack O’Flynn, writer Maria Sledmere and curator Katie O’Grady which took place from April to August 2021. This collaboration will be showcased in an exhibition at French Street Studios, Glasgow, featuring new works from O’Flynn and Sledmere which travel through poetry, sculptural entities and dreams of impossible possibilities.

This project was formed in a concert – along mixtapes, Tarot readings, zoom calls and shared research. We present it here as multiple sensual journeys; to an exhibition of hyper-foxes and tenderly crumbling foliage, through a publication of lichenous illusions and rummaging thought and in a selection of music and voices which trailed our imaginings.

Intertwining themes of ecological thought, world building and re-enchantment we sought to un-ravel the question: how can we act and think in this present moment to ensure positive change to our relationship with the world around us? The action and thinking which we wandered became located in small and monumental formats – enacted in the everyday and in how we create and build the future. We were enveloped by uncertain certainty, whether apparent through non-human thought, the possibilities of visual art and poetry or the endorsement of magic. Living in a world brimming with unease by climate crisis and extreme inequality – brought upon by extractive capital, far-right strategies and carceral logics – we wished to communicate a different model of awareness that could refuse these structures and re-imagine being a Being.

Exploring this sentiment O’Flynn and Sledmere have created a body of work that opens a portal to a forest of vibrating thought. One of galloping states, lockdown meanderings and a lyrical suffusion through language and art that prompts how we can think and imagine differently.

Please enjoy this digital showcase of The Palace of Huming Trees and, if you can, come to visit its physical iteration at French Street Studios, 103 – 109 French Street, Glasgow. Open July 30th to August 8th 11 AM to 5 PM (closed Monday and Tuesday) with a preview on July 29th 6 PM – 9 PM. Book to attend exhibition via Eventbrite here and to attend preview here.

More info at the exhibition website.

The exhibition also comes with a book of poetry, illustration and essaying, The Palace of Humming Trees.

Available to order for £12.99 – Contact details for ordering available on the website above.

Excited to announce a new installation I’ve been involved in as part of A+E Collective. From The NewBridge website:

This online installation explores the relationship between sustainability and dreaming, offering a space to collectively share our dreams and have discussions surrounding these broader topics. The Dream Turbine was conceived by A+E Collective in collaboration with Niomi Fairweather and Jessica Bennett, as part of the Overmorrow Festival.

A turbine (from the Latin ‘turbo’, meaning vortex) is a device that harnesses the kinetic energy of fluid, turning this into a rotational motion which can generate electricity or otherwise ‘work’. From windmills to waterwheels, turbomachines are a crucial part of our energy history. The Dream Turbine is a speculative, participatory turbomachine for stimulating, processing, converting and sharing sustainable and postcapitalist imaginaries.

From Earth Day to early summer 2021, A+E Collective will be taking to cyberspace and installing The Dream Turbine at The NewBridge Project. In solidarity with The NewBridge Project’s values of cooperation, adaptation, environmental and social justice, The Dream Turbine hopes to promote alternative, non-extractive ways of thinking, desiring, memorialising and living through various ongoing crises as individuals and collectives.

More information here.

A+E Collective website.

Instagram: @a.e.collective

‘Hear me, hear my silence. What I say is never what I say but instead something else. When I say “abundant waters” I’m speaking of the force of body in the waters of the world. It captures that other thing that I’m really saying because I myself cannot.’

— Clarice Lispector, Água Viva

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin

— Adrienne Rich, ‘Diving into the Wreck’

On becoming a body,

the little abundant shines and its pores are clotted with dust.

I saw what sound it was a wave makes

when startled by gestures towards this torsion

a long beach, the false irrigation of beautiful islands.

The melody was a long intimation of losing faith

in what is meant by a certain colour, not

this blue which runs in the prussian rain.

I want to run up the spine of your back

and settle the amygdala city, tie

my lyrical wrists in mobius fibres

and return the rights to speech.

Do you want to continue?

He was born and beautiful,

he might have seizures. We interfere in definition.

The depression of time is a beautiful curve

in the small of morning, named

after the call you wanted.

Blue dust of feeling.

Blue dust of biblical name.

I worry for his tiny heart.

Glycolic, afloat

in the radical millions

when I say this bird

is a nameless bird, plotting

and pecking the wreck

I go down

in such hunger

I go down

without formula.

Not this.

The world is stuck.

I sing to you

in the echo, in the rich

and greatest loss.

Who hurt us?

I had a dream we were swimming

in the San Pedro Bay, just like the video

it was almost sunny. There will come a time

when my car won’t start

if I ever have a car

in a lightless world

the structure of passion is a ritzy hotel.

Your hour is a fucking astronaut.

Imagine Disney injected

arterial dreams

this crudely.

Imagine a fire in the minibar

at the back of your mind.

As the relation to your wreck

I call it ship, I still want

the elsewhere conduit of thoughts

to sign my brain as treeware

in the black black gold

my oleochemical, fear of soap

and gaussian world is a kitten.

She burns it all up.

On becoming this back-lit

history of pixels, we pour into jars

the last of sea-glass, liquid shingles, I cut the bird

into salad I cut this sort of pristine hope

to feed the kitten.

I thought the picket

was shining in rain, a sound.

Something is drawing us out.

I make a romance from your shoes

and the kissable way of these days

is a no-show, mewing, the marketing

of genital shame, the apocalypse breakfast

tastes of salt. Come back into my life,

I always found you

with a breath laced in pesticide,

a currency of morphine

dreaming me

back like a thrush, I want to wreck

the multitude of this song

with its hyperthermia, its oil-made

hide of feathers.

You want me to be less literal,

littoral I like your wildlife.

Lighter, somewhere

what we see

without reason.

What can soak

up the dark this good.

I like your messages.

I like to react with my abstract halo.

The rediagnosis read depression, to kill

not clean the long and beautiful rain.

Prising the daylight from its packet

I want April, a lot

of lilac song.

I go down to the nervous water,

deep in mammalian blood

I am, I am

not breath, not bird

west coast

my body is a poke of air

in the book. And it lets in

the crudest wind, reminder of gold

in the room where we woke up last October

in my father’s house

in the valley

where frost never leaves the cornicing forests

or sets its voice to speak

for the sodas and junipers.

If we could just avalanche into orange

like the song, Mount Eerie would be a genuine place

to kill or not kill the birds we oiled

in the prussian rain, they gleam

like unemployment

doesn’t in the colourless streets.

We share a little nest

of noctilucent materials.

I was jobless

as the natural light, listening

to your comedown opening chord

which is to say, I think we should stop

seeing, I think we should stop

seeing at all. I roll around

in the oil of this

happiest adderall

to sob uncontrollable

to stop trying to see you

as snow,

if a former love should fall

very cool, like a two-minute Uber

costs less than lunch.

Ducter, he

could break me

the ultimate mosh is us.

I have said that he could and he could

I have said that too much.

To float like capital

back to your panic

I smooth my sleepless residuals.

Ducked it, ducked it

you come back, holding a blink

to know

that time is a gleam, we had a guest speaker

passing out in notional

structures of passion.

I wrote everything down.

It is a wreck to think in the beautiful rain.

It is all that dissolves

to remember

I hope to meet in code someday

again, to set this

in parenthesis, very lightly

choosing to run

the artificial palms

horizontal across your eventide.

This was all ours in the poem.

Prospering, we’d know

each other

so much more than mineral

in the flotsam

way, a lot of coffee

fills our faultlines

and the tar sands sing, and the quicksands

go astray, what of the waters

don’t touch what we were

to sing something

hurting, to rainbow

the quoted weight of your heart

is only debris

I go so long in the rain

to break her

I go so long in the run

as to make a beach

in loops of oil

to empty my purse

of mermaids, to feel like

the only decorated islands

in the United States of America.

*

This poem was written following a talk I gave on Energy (W)rites: Telling the Embodied Stories of Energy, as part of The Curatorial Fellowship: With the North Sea series at Peacock Visual Arts, Aberdeen. It responds specifically to Lana Del Rey’s ‘The Greatest’, where the mournful twangs of a classic rock ballad play out over sunset scenes of Long Beach in the San Pedro Bay, whose four decorative ‘Astronaut Islands’ were built in the sixties to camouflage offshore oil derricks and muffle their sound pollution. Classic rock is a genre and industry founded on oil: vinyl is a type of plastic made from ethylene (found in crude oil) combined with chlorine (found in salt). PVC, the resultant material, is a highly toxic form of plastic, for both our health and the environment. Perhaps it’s only ‘natural’ that Lana would style a kind of vinyl-nostalgia to sing of various kinds of tainted existence. If her earlier work was dubbed ‘Hollywood sadcore’, we might note this recent aesthetic shift as something more like ‘anthropocene sadcore’: where the cinematic eulogising of wasted youth, ‘the greatest’ American Dream, is played out against the false beauty of late twentieth-century petroscapes. But alongside oil there is also water, and the brilliance of light, tone and pigment. There is haze and trace and repeat. Lush tints within variant opacity. A khoratic space where the colours soften or harshen into each other and something of form is held between, with varying paleness or intensity. It could be Billie Eilish singing of ‘burning cities / And napalm skies’ in the apocalypse unconscious of her song ‘Ocean Eyes’; it could be a flare of orange burning into Grimes’ ‘permanent blue’, its elegia for opioid bliss and extinction. The weird pleasure vistas of a scene we can’t quite name. An improvised blur or break. What the water speaks as a force of shimmer. The accompanying visual works are by multimedia artist and sculptor Jack O’Flynn.

Poem co-written with Kirsty Dunlop on 30th July, in response to Bridget Riley’s exhibition at Edinburgh’s National Gallery of Scotland. Sketches by Maria Sledmere.

Lozenges of Responsive Eye

i.

A jail cell of pin-striped trousers

And jelly is stretching

Ben and Bridget’s collaborative secret:

Stripes vs polka dots; battle of personality

For personable sense

A ballet of silk as scream

All Jack Wills plagiarists

Pluck a little learnèd relief,

My trypophobic kitsch.

ii.

The over-blunt rust of the pencil takes over

With Anthropologie’s rich, ornamental fruit

All that plasticine:

infinite optic nude.

E= Mc2= seafoam equalities

Teeth keys,

No,

Keys having sex

Some sexy metal grinding grind core

Towards the yonic aporia.

iii.

Runway & Egyption palette of

Patchwork architecture w/ international sunset

Peach plastic, has to be fantastic

Too many black hole doors of exhibited thrill.

& Wind massage

Pulses the butterfly, connects such dots.

iv.

Ribbony eel of clandestine dreams:

Gel pen explosion, want that scented mint,

Bubblegum and banana

=> Warp nostalgia

Almost forgot about my cola phobia

Piña colada for the pleistocene.

v.

There’s a woman reading behind her triangles,

Meeting the tender tremble:

Slimy triangulation overlaid

Blurring pyramidal bluntness

Blooming bud above belly a bus of mixed feeling;

Keep looking, unhooking

The ghostly room and pastel pleasures.

I always have this sensation, descending the steps at Edinburgh’s Waverley Station, of narratives colliding. It’s a kind of acute deja vu, where several selves are pelting it down for the last train, or gliding idly at the end point of an evening, not quite ready for the journey home. The version that is me glows inwardly translucent, lets in the early morning light, as though she might photosynthesise. I remember this Roddy Woomble song, from his first album, the one that was sorrow, and was Scotland, through and through as a bowl of salted porridge, of sickly sugared Irn Bru. ‘Waverley Steps’, with its opening line, ‘If there’s no geography / in the things that we say’. Every word, I realise, is a situation. Alighting, departing; deferring or arriving. It’s 08:28 and I’m sitting at Waverley Station, having made my way down its steps, hugging my bag while a stranger beside me eats slices of apple from a plastic packet. I’ve just read Derek Jarman’s journal, the bit about regretting how easily we can now get any fruit we want at any time of year. He laments that soon enough we’ll be able to pick up bundles of daffodils in time for Christmas. The apples this girl eats smell of plastic, of fake perfume, not fruit. I’m about to board a train that will take me, eventually, to Thurso and then on via ferry to Orkney. I wonder if they will have apples on Orkney; it’s rumoured that they don’t have trees. Can we eat without regard to the seasons on islands also?

I needn’t have worried. Kirkwall has massive supermarkets. I check my own assumptions upon arrival, expecting inflated prices and corner shops. I anticipated the sort of wind that would buffet me sideways, but the air is fairly calm. I swill a half pint of Tennents on the ferry, watching the sun go down, golden-orange, the Old Man of Hoy looming close enough to get the fear from. Something about ancient structures of stone always gives me vertigo. Trying to reconcile all those temporal scales at once, finding yourself plunged. A panpsychic sense that the spirit of the past ekes itself eerily from pores of rock. Can be read in a primitive braille of marks and striations. We pick our way through Kirkwall to the SYHA hostel, along winding residential streets. I comment on how quiet it is, how deliciously dark. We don’t see stars but the dark is real, lovely and thick. Black treacle skies keep silent the island. I am so intent in the night I feel dragged from reality.

Waking on my first day, I write in my notebook: ‘the sky is a greyish egg-white background gleaming remnant dawn’. In the lounge of the hostel, someone has the telly on—news from Westminster. Later, I’m in a bookshop in Stromness, browsing books about the island while the Radio 2 Drivetime traffic reports of holdups on motorways circling London. Standing there, clasping Ebban an Flowan, I feel between two times. A slim poetry volume by Alec Finlay and Laura Watt, with photographs by Alastair Peebles, Ebban an Flowan is Orkney’s present and future: a primer on marine renewable energy. Poetry as cultural sculpting, as speculation and continuity: ‘there’s no need to worry / that any wave is wasted / when there’s all this motion’. New ideas of sustainability and energy churn on the page before me, while thousands down south are burning up oil on the London orbital.

When we take a bus tour of Mainland Orkney’s energy sources, we play a game of spotting every electric car we see. Someone on the bus, an academic who lives here, knows exactly how many electric cars there are on the island. There’s a solidarity in that, a pride in folk knowledge, the act of knowing. On the train up to Thurso, I started a game of infrastructure bingo, murmuring the word whenever I spotted a pylon, a station or a turbine. Say it, just say it: infrastructure. Something satisfying in its soft susurration, infra as potential to be both within and between, a shifting. Osmosis, almost. The kinesis of moving your lips for fra, feeling a brief schism between skin and teeth. A generative word. Say it enough times and you will summon something: an ambient awareness of those gatherings around you, sources of fuel, object, energy.

The supermarkets in Kirkwall seem like misplaced temples. This was me idealising the remoteness of islands, wanting to live by an insular, scarcer logic. The more we go north, the more scarcity we crave—a sort of existential whittling. Before visiting, I envisioned the temperature dropping by halves. On the first night, warm in my bed, I write: ‘To feel on the brink of something, then ever equi-distant’. The WiFi picks up messages from home. Scrolling the algorithmic rolls of Instagram, I feel extra-simultaneous with these random images, snapshots of happenings around the world. Being on an island intensifies my present. In Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun (2016), a memoir of recovery and return on Orkney, Liptrot writes of ‘waiting for the next gale to receive my text messages’. On the whims of billowing signal, we wait for news of the south to arrive. Maybe I was an island and I wanted my life elsewhere to vanish, disappear in a wall of wind; I wanted to exist just here, in a hullabaloo of nowness.

I say an island, but of course Orkney is more an archipelago. And I’m on the Mainland, home to the burghs of Stromness and Kirkwall. Here for the ASLE-UKI conference, there wasn’t time to visit the harbour at Scapa, or the neolithic village of Skara Brae or the stone circle Ring of Brodgar. I spend most of my time in the town hall opposite Kirkwall’s impressive, sandstone cathedral, aglow by night with fairy lights strung in surrounding trees. Yes, trees. Orkney has trees. They are often gnarled-looking and strange, stripped by wind or held up inside by steel plinths. Anthropocene arboreal hybrids. But still they are trees. Using my plant identification app, I find hazels and birches. Autumn is traceable in the swirls of thin leaves that skirt the pavement, tousling our sense of a general transition.

At one point in the trip, we visit the Burgar Hill Energy Project in Evie, alighting from the bus to stand underneath several massive turbines. The sound is wonderful, a deep churning whirr that feels like the air pressed charge on repeat. Under the chug chug chug of those great white wings we gathered, listened, moved and dispersed. I watch as our tight knit group begins to fragment; we need time apart to absorb this properly, little cells bouncing off and away from each other, quietly charged, loosening dots of pollen. Some of us finding the outer reach of the hill, looking for a view or panorama, leaning back to snap a photograph. I film the shadows windmilling dark the rough green grass. Capturing the turbines themselves seemed almost obscene. I don’t know why I was making them into idols, afraid to reduce them to pictures. It was easier to glimpse them in pieces, a flash of white, synecdoche. My friend Katy and I agreed the best photos were the ones out of focus, a bird-like blur against the blue.

Places I have been hit by wind:

I am an air sign, Gemini, and there is something about losing your breath to elemental forces. I think I once finished a poem with a phrase like, ‘lashing the planetary way of all this’. We used to stand in the playground at school, brandishing our jackets like polyester wings, letting the wind move us forward, staggering in our lightweight bodies, our childish intuition of the way of the world. The pleasure in surrendering. Making of your body a buffeted object. Returning to Glasgow, I soon find myself hit with a cold, preemptive fresher’s flu; a weight on my chest, a diaphragm lag. A sense of my body heaving against itself.

On Orkney, I can smell the salt from the sea. Earlier in the summer, I was struck with wisdom tooth pain, the kind that requires salt-water rinses every half hour, not to mention agonised gargles of whisky. Wasting my precious bottle of Talisker. Amid the haze of those painkiller days, I felt closer to an elemental heat. Metonymically, I was inhaling islands. The taste of self-preservation, of necessary self-sustenance, is never as strong and unwanted as when you want a part of yourself to be wrenched out of you. Pulling teeth is an easy metaphor for lost love, or other forms of psychic distress. Breaking apart, making of the self an archipelago. There’s that song by The National, ‘I Should Live in Salt’, which always sticks in my head in granular form, occasional line. Refrain of refrains, ‘I should live in salt for leaving you behind’. I never knew whether Matt Berninger was singing about preservation or pain, but I saw myself lying down in a kelp bed, child-size, letting the waves lap over my body, salt suffusing the pores of my skin. Begin again, softer.

The rain here is more a tangential shimmer. I wake up to it, dreaming that my window was broken and no-one would bother to fix it. Fear of boundaries loosened, the outside in. The future as a sheet of glass, a shelf you could place your self on and drink. Salt water rinse and heat of whisky. We leave the hostel early and wander beyond the Kirkwall harbour, to the hydrogen plant bordering an industrial estate. Katy and I discussed our fondness for industrial estates as homely reminders. She would go running, and wherever she ran the industrial zones were inevitable. As if in any city you would reach that realm, it called you in with its corrugated fronts and abrasive loneliness. My love for the canal, biking up through Maryhill where the warehouses watch serenely over you, loom behind trees, barely a machinic rumble disturbing the birds. We traced the edge of a man-made waterfront, a crescent curving lip of land. The way it curled was elliptical, it didn’t finish its inward whorls of land upon water, but still I thought of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, or the cinnamon buns I bought from the Kirkwall Tesco. Finding a bench, we ate bananas for breakfast, looking out at the grey-blue sea, our fingers purpling with the cold. I like to think of the banana, Katy said, as a solid unit of energy. Here we were, already recalibrating reality by the logic of pulse and burn and calories. Feeling infra.

I love the words ‘gigawatt’, ‘kilocal’, ‘megabyte’. I like the easeful parcelling up of numbers and storage and energy. I am unable to grasp these scales and sizes visually or temporally, but it helps to find them in words.

We learn about differences between national and local grids, how wind is surveyed, how wave power gets extracted from the littoral zone. My mind oscillates between a sonar attentiveness and deep exhaustion, the restfulness gleaned from island air and waking with sunrise. I slip in and out of sleep on the bus as it swerves round corners. I am pleasantly jostled with knowledge and time, the precious duration of being here. Here. Here, exactly. This intuition vanishes when I try to write it. A note: ‘I know what the gaps between trees must feel like’. Listening to experienced academics, scientists and creatives talk about planes, axes, loops and striations, ages of ages, I find myself in the auratic realm of save as…, dwelling in the constant recording of motion, depth and time. Taking pictures, scribbling words, drawing maps and lines and symbols. We talk of Orkney as a model for the world. Everything has its overlay, the way we parse our experience with apps and books and wireless signals. Someone takes a phone call, posts a tweet. I scroll through the conference hashtag with the hostel WiFi, tracing the day through these crumbs of perspective, memories silently losing their fizz in the night.

I grew up by the sea, in Maybole, Ayrshire (with its ‘blue moors’, as W. S. Graham puts it), but a lot of my thalassic time was spent virtually. I loved video games like The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, where the narrative happened between islands, where much of the gameplay involved conducting voyages across the sea. The interstitial thrill of a journey. There were whirlpools, tornados, monsters rising from the deep. On Maidens Harbour, I could hardly reach that volcanic plug of sparkling granite, the Ailsa Craig, or swim out to Arran; virtually, however, I could traverse whatever limits the game had designed. The freedom in that, of exploring a world already set and scaled. Movement produced within constraint. In real life, mostly our bodies and minds constrain. What excites me now is what I took for granted then: the salt spray stinging my lips, the wind in my hair, the glint of shells bleached clean by the sea; a beautiful cascade of cliches that make us.

‘To wake up and really see things…passages from a neverland.’ Back in Glasgow, fallen upon familiar nocturnal rhythms, I find myself craving the diurnal synchrony I achieved in Orkney. Sleepy afternoons so rich in milky light. The vibrational warmth of the ferry’s engine, activating that primitive desire for oil, the petrol smell at stations as my mother filled up the car for journeys to England. My life has often been defined by these journeys between north and south, born in Hertfordshire but finding an early home in Ayrshire. Swapping that heart for air, and all porosity of potential identity. Laura Watt talked of her work as an ethnographer, interviewing the people of Orkney to find out more about their experiences of energy, the way infrastructural change impacts their daily lives, their health, their business. Within that collaboration, she tells us, there’s also a sense of responsibility: stories carry a personal heft, something that begs immunity from diffusion. Some stories, she says, you can’t tell again. The ethics of care there. I wonder if this goes the same for stone, the stories impregnated within the neolithic rocks we glimpse on Orkney. Narrative formations lost to history’s indifferent abstraction, badly parsed by present-day humans along striated lines, evidence of fissure and collision. All that plastic the ocean spits back, co-evolutions of geology and humans. Plastiglomerates along the shore. But Orkney feels pure and relatively litter-free, so goes my illusions, my sense of island exceptionalism. I become more aware of the waste elsewhere. The only person I see smoking, in my whole time there, is a man who speeds his car up Kirkwall’s high street. Smoke and oil, the infinite partners; extraction and exhaustion, the smouldering of all our physical addictions. Nicotine gives the body a rhythm, a spike and recede and a need.

We learn of a Microsoft server sunk under the sea, adjacent to Orkney. There’s enough room in those computers, according to a BBC report, to store ‘five million movies’. And so the cloud contains these myriad worlds, whirring warm within the deep. Minerals, wires and plastics crystallise the code of all our text and images. Apparently the cooler environment will reduce corrosion. I remember the shipyard on Cumbrae, another island; its charnel ground of rusted boats and iron shavings. The lurid brilliance of all that orange, temporal evidence of the sea’s harsh moods, the constant prickle of salt in the air. The way it seems like fire against all those cool flakes of cerulean paint. I wrote a blog post about that shipyard once, so eager to mythologise: ‘Billowing storms, sails failing amidst inevitable shipwreck. It’s difficult to imagine such disasters on this pretty island, yet there is an uncanny sense to this space, as if we have entered a secret porthole, discovered what was supposed to be invisible to outsiders…The quietness recalls an abandoned film set’. Does tourism lend an eerie voyeurism to the beauty we see, conscious of these objects, landscapes and events being photographed many times over? Perhaps the mirage of other islands and hills glimpsed over the blue or green is more the aura of our human conceptions, archival obsession—the camera lights left buzzing in the air, traced for eternity.

I come to Orkney during a time of transition, treading water before a great turn in my life. Time at sea as existential suspension. There have been some departures, severings, personal hurts, burgeoning projects and new beginnings. A great tiredness and fog over everything. ‘Cells of fuel are fuelling cells’. At the conference, my brain teems with this rich, mechanical vocabulary: copper wires and plates and words for wattage, transmission, the reveries of innovation. There is a turning over, leaf after leaf; I fill up my book with radials, coal and rain. My mind attains a different altitude. I think mostly about the impressions that are happening around me: the constant flow of conversation, brought in again as we move between halls and rooms, bars and timelines in our little human estuaries. We visit Stromness Academy, to see Luke Jerram’s ‘Museum of the Moon’: a seven-metre rendition of lunar sublimity, something to stand beneath, touch, lie under. I learn the word for the moon’s basaltic seas is ‘Maria’, feel eerily sparked, spread identity into ether. We listen, quietly, in the ambient dark, taking in composer Dan Jones’ textures of sound, the Moonlight Sonata, the cresting noise of radio reports—landings from a future-past, a lost utopia.

On Friday night, Katy and I catch the overnight ferry back to Aberdeen. Sleep on my cinema seat has a special intensity, a falling through dreams so vivid they smudge themselves on every minute caught between reading and waking. Jarman’s gardens enrich my fantasy impressions, and I slip inside the micro print, the inky paragraphs. I dream of oil and violets and sharp desire, a pearlescent ghost ship glimmer on a raging, Romantic sea. Tides unrealised, tides I can’t parse with my eyes alone; felt more as a rhythm within me. Later, on land I will miss that oceanic shudder, the sense of being wavy. I have found myself like this before, chemically enhanced or drunk, starving and stumbling towards bathrooms. We share drinking tales which remind me of drowning, finding in the midst of the city a seaborne viscosity of matter and memory, of being swept elsewhere. Why is it I always reach for marinal metaphor? Flood doors slam hard the worlds behind me. There are points in the night I wake up and check my phone for the time, noticing the lack of GPRS, or otherwise signal. I feel totally unmoored in those moments, deliciously given to the motioning whims of the ferry. Here I am, a passenger without place. We could be anywhere, on anyone’s ocean. I realise my privilege at being able to extract pleasure from this geographic anonymity, with a home to return to, a mainland I know as my own. The ocean is hardly this windswept playground for everyone; many lose their lives to its terminal desert. Sorrow for people lost to water. Denise Riley’s call to ‘look unrelentingly’. I sip from my bottle, water gleaned from a tap in Orkney. I am never sure whether to say on or in. How to differentiate between immersion and inhabitation, what to make of the whirlwinds of temporary dwelling. How to transcend the selfish and surface bonds of a tourist.

The little islands of our minds reach out across waves, draw closer. I dream of messages sent from people I love, borne along subaquatic signals, a Drexciya techno pulsing in my chest, down through my headphones. My CNS becomes a set of currents, blips and tidal replies. A week later, deliriously tired, I nearly faint at a Wooden Shijps gig, watching the psychedelic visuals resolve into luminous, oceanic fractals. It’s like I’m being born again and every sensation hurts, those solos carried off into endless nowhere.

Time passes and signal returns. We wake at six and head out on deck to watch the sunrise, laughing at the circling gulls and the funny way they tuck in their legs when they fly. These seabirds have a sort of grace, unlike the squawking, chip-loving gulls of our hometowns, stalking the streets at takeaway hour. The light is peachy, a frail soft acid, impressionist pools reflecting electric lamps. I think of the last lecture of the conference, Rachel Dowse’s meditations on starlings as trash animals, possessing a biological criticality as creatures in transition. I make of the sky a potential plain of ornithomancy, looking for significant murmurations, evidence of darkness to come. But there is nothing but gulls, a whey-coloured streak of connected cumulus. The wake rolls out behind us, a luxurious carpet of rippling blue. We are going south again. The gulls recede. Aberdeen harbour is a cornucopia of infrastructure, coloured crates against the grey, with gothic architecture looming through morning mist behind.

Later I alight at the Waverley Steps again. Roddy in my ear, ‘Let the light be mined away’. My time on the island has been one of excavation and skimming, doing the work of an academic, a tourist, a maker at once. Dredging up materials of my own unconscious, or dragging them back again, making of them something new. Cold, shiny knowledge. The lay of the heath and bend of bay. I did not get into the sea to swim, I didn’t feel the cold North rattle right through my bones. But my nails turned blue in the freezing wind, my cheeks felt the mist of ocean rain. I looked at maps and counted the boats. I thought about what it must be like to cut out a life for yourself on these islands.

Home now, I find myself watching badly-dubbed documentaries about Orkney on YouTube, less for the picturesque imagery than the sensation of someone saying those names: Papay, Scapa, Eday, Hoy. Strong names cut from rock, so comforting to say. I read over the poems of Scotland’s contemporary island poets, Jen Hadfield for Shetland, Niall Campbell for Uist. Look for the textures of the weather in each one, the way they catch a certain kind of light; I read with a sort of aggression for the code, the manifest ‘truth’ of experience— it’s like cracking open a geode. I don’t normally read like this, leaving my modernist cynicism behind. I long for outposts among rough wind and mind, Campbell’s ‘The House by the Sea, Eriskay’: ‘This is where the drowned climb to land’. I read about J. H. Prynne’s huts, learn the word ‘sheiling’. Remember the bothies we explored on long walks as children. There’s a need for enchantment when city life churns a turbulent drone, so I curl into these poems, looking for clues: ‘In a fairy-tale, / a boy squeezed a pebble / until it ran milk’ (Hadfield, ‘The Porcelain Cliff’). Poetry becomes a way of building a shelter. I’m struck with the sense of these poets making: time and matter are kneaded with weight and precision, handled by pauses, the shape-making slump of syntax. Energy and erosion, elemental communion. Motion and rest. My fragile body becomes a fleshwork of blood and bone and artery, hardly an island, inclined to allergy and outline, a certain porosity; an island only in vain tributary. I write it in stanzas, excoriate my thoughts, reach for someone in the night. I think about how we provide islands for others, ports in a storm. Let others into our lives for temporary warmth, then cast ourselves out to sea, sometimes sinking.

Why live on an island? In Orkney we were asked to think with the sea, not against it. To see it not as a barrier but an agential force, teeming with potential energy. Our worries about lifestyle and problematic infrastructure, transport and connection were playfully derided by a local scholar as ‘tarmac thinking’. Back in a city, I’ve carried this with me. The first time I read The Outrun was in the depths of winter, 2016, hiding in some empty, elevated garrett of the university library. I’d made my own form of remoteness; that winter, more than a stairwell blocked me off from the rest of existence. Now, I read in quick passages, lively bursts; I cycle along the Clyde at night and wonder the ways in which this connects us, its cola-dark waters swirling northwards, dragged by eventual tides. I circle back to a concept introduced by anthropologists at Rice University, Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer, ‘sister cities of the Anthropocene’: the idea that our cities are linked, globally, by direct or vicarious physical flows of waste, energy and ecological disaster. This hydrological globalisation envisions the cities of the world as a sort of archipelago, no metropolis safe from the feedback loops of environmental causality, our agency as both individuals and collectives. On Orkney, we were taught to think community as process, rather than something given. I guess sometimes you have to descend from your intellectual tower to find it: see yourself in symbiosis; your body, as a tumbled, possible object: ‘All arriving seas drift me, at each heartbreak, home’ (Graham, ‘Three Poems of Drowning’).

[An essay on anorexia, femininity, adolescent pain & writing the body]

I distinctly remember the first time I watched someone apply liquid liner to their eyes. We stood in the Debenhams toilets before a sheet of unavoidable mirror. She emptied her rucksack of trinkets and tools, drew out a plastic wand with a fine-tip brush and skimmed the gooey ink skilfully over her lids, making curlicues of shimmering turquoise. Her irises were a kind of violent hazel, whose flecks of green seemed to swim against the paler blue. She was very tall and for a while, very thin. She had a nickname, a boyfriend and sometimes she shoplifted; in my head, she was the essence of teenage success. Only later, in the maelstrom of a drunken night out down the beach, do I discover she’s heavily bulimic.

A year or so passes since this first incident, watching my friend slick her eyes with electric blue. I have since learned to ink my own eyes, draw long Egyptian lines that imitate that slender almond shape I long for. My makeup is cheap and smudges. I have grown thinner and people are finally starting to notice.

My mother goes quiet when we do the shopping. She tells me to move out the aisle and I ask what’s wrong. People are staring, she says. I turn around and there they are by the stacks of cereal, mother and daughter, gesturing at my legs and whispering: stick insect, skeleton. A feel a flush of hot pride, akin to the day in primary school when I got everyone to sign my arms with permanent marker—this sudden etching of possession. I am glad I lack this conspiratorial relationship with my own mother, reserving comments on others for the page instead, for my skin. My pain and frustration are communicated bodily: I slink into the shadows, sleeping early, avoiding meals. When people stare, they imbue me with a visibility I desire to erase. I should like better to float around them intangibly, diaphanous, a veil of a name they can’t catch. Instead it rests on everyone’s tongue, thick and severe: anorexic.

It took a week for all the names to fade from my arms; it takes much longer to erase a single label.

In the television series Girls, Lena Dunham’s character reveals that she got tattoos as a teenager because she was putting on weight very quickly and wanted to feel in control of her own body, making fairytale scripture of her skin. In Roald Dahl’s short story, ‘Skin’, an old man gets a famous artist to tattoo the image of a gorgeous woman on his back, the rich pigment of ink like a lustrous ‘impasto’. Years later, art dealers discover his fleshly opus and proceed to barter, literally, on the price of his skin. The story reveals the synecdochical relations between the body, the pen and the value of art. Everything is a piece of something else, skin after skin after skin. In Skins, Cassie Ainsworth gazes into the camera: I hate my thighs. With black marker, she scrawls her name onto her palm; she’s got a smile that lights up, she’s in love. Everyone around her rolls cigarettes, swaps paper skins like scraps of poetry. It feels dirty, the chiaroscuro mood of sunshine and sorrow. Her whole narrative purpose is the spilling of secrets, of human hurt turned to vapour, smoke. Wow, lovely.

For a while, my name mattered less than my skin. There were levels of weight to lose, dress sizes which signified different planes of existence. Over and over, I would listen to ‘4 st. 7lbs’ by the Manic Street Preachers, Richey Edwards’ lyrics spat over a stomach-churning angst of guitar: ‘Self-worth scatters self-esteem’s a bore / I’ve long since moved to a higher plateau’. That summer, ten years ago now, I would walk for hours, the sun on my skin. All the fields stretched out before me like fresh pages of impossibility; my life was a mirage on the flickering sea. I thought of liquid turquoise ink, the friend in the mirror. I started to forget the details of her face, so she blurred into the impressionist portraits I wrote about in school.

Midsummer’s eve; I laid down in one of those fields. With bone-raw fingers, I counted the notches of my spine. Even in free-fall you never feel quite free.

I was obsessed with Richey’s ghost. He disappeared decades ago and they never found evidence of his body. I wanted to evaporate like that, leave my abstracted car somewhere along the motorway; step into the silence of anonymity. Richey wrote screeds of furious notes: ‘I feel like cutting the feet off a ballerina’. There it was: the dark evaporation of resentment and envy. Around this time, Bloc Party released A Weekend in the City, a record that uses Edwards’ lyric to express the racial frustration of being made Other by a racist society. I was acutely aware that the figure of a ballerina, the doll-like white girl, was a divisive source of symbolic desire. We inscribe such societal alignments on the female body, and shamefully I was more than ready to fall into place, to shed the necessary weight. But what I wanted was less the bloody violence of a crippled ballerina, and more the success of erasure.

In Zelda Fitzgerald’s only novel, Save Me the Waltz,the protagonist Alabama trains to be a ballerina late in her twenties, too late to ascend to any real career success. Here was ballet, the pre-adolescent world of waif-thin bodies and she was a mother, a woman—someone who once gave birth, who was strong in flesh. She reaches this frenzied state of beautiful prudence, honing her body to the point where every movement and thought is guided by the waltzing beat, the perfect arabesque: ‘David will bring me some chocolate ice cream and I will throw it up; it smells like a soda fountain, thrown-up, she thought’. I could attest to that. Ben and Jerry’s, swirls of it marbling the toilet bowl, clots of sweetness still clear in your throat. Fitzgerald’s sentences stream towards endless flourish. Alabama makes herself sick with the work, her desire is lustily bulimic. She gets blood poisoning, finds herself hospitalised with tubes in her body, drip-fed and cleansed by the system. I thought of how I wanted to photosynthesise, survive on nothing but air and light. Like a dancer, I was honing my new ascetic life.

Sometimes at night, the old ticker would slow to such a crawl and I thought it would stop in my sleep, sink like a stone. A girl I met on the internet sent me a red-beaded bracelet in the post and in class I’d twirl each plastic, pro-ana ruby, imagining the twist of my own bright sinew as later I’d stretch and click my bones.

I was small, I was sick. I used to write before bed, write a whole sermon’s worth of weight-loss imperatives; often I’d fall asleep mid-sentence and awake to a pool of dark ink, flowering its stain across my sheets. Nausea, of one sort or another, was more or less constant. Waves would dash against my brain, black spots clotting my vision. I moved from one plane or scale to another, reaching for another diuretic. I tried to keep within the lines, keep everything in shape.

Often, however, I thought about water, about things spilling; I drank so much and yet found myself endlessly thirsty. Esther Greenwood in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, trying to drown, being spat back out by the sea: I am I am I am.

I’m fine I’m fine I’m fine. The familiar litany.

Something buoyed up, started showing on the surface. People could read the wrongness in the colour of my skin, all that mottled and purpling blood like a contrast dye my body had been dipped in. Against my pallid aquatic hue, I used to envy the warm and luxurious glow of other people’s skin. I sat on a friend’s lap and he freaked out at the jut of my bones. Someone lifted me and we ran down the road laughing and they were like, My god you’re so light. The sycamores were out in full bloom and I realised with a pang it would nearly be autumn. Vaguely I knew soon I would fall like all those leaves.

Anorexia is an austerity of the self. To fast is to practice a refusal, to resist the ideological urge to consume. To swap wasteful packs of pads and tampons for flakeaway skin and hypoglycaemic dreams. Unlike with capitalism, with anorexia you know where everything goes.

The anorexic is constantly calculating. Her day is a series of trades and exchanges: X amount of exercise for X amount of food; how much dinner should I spread around the plate in lieu of eating? It was never enough; nothing ever quite added up. My space-time melted into a continuous present in which I constantly longed for sleep. The past and future had no bearing on me; my increasingly androgynous body wasn’t defined by the usual feminine cycles—life was just existing. This is one of the trickiest things to fix in recovery.

Dark ecologist Timothy Morton says of longing: it’s ‘like depression that melted […] the boundary between sadness and longing is undecidable. Dark and sweet, like good chocolate’. Longing is spiritual and physical; it’s a certain surrender to the beyond, even as it opens strange cavities in the daily. The anorexic’s default existential condition is longing: a condition that is paradoxically indulgent. Longing to be thin, longing for self, dying for both. The world blurs before her eyes, objects take on that auratic sheen of desire. Later, putting myself through meal plans that involved slabs of Green & Black’s, full-fat milk and actual carbs, the dark sweet ooze of depression’s embrace gradually replaced my disordered eating. I wondered if melancholia was something you could prise off, like a skin; I saw its mise-en-abyme in every mirror, a curious, cruel infinitude.

In Aliens and Anorexia, Chris Kraus asks: ‘shouldn’t it be possible to leave the body? Is it wrong to even try?’. What do you do when food is abstracted entirely from appetite? What happens when life becomes a question of pouring yourself, gloop by gloop, into other forms? What is lost in the process?

I started a diary. I wrote with a rich black Indian ink I bought from an art supplies store. The woman at the counter ID’d me, saying she’d recently had teenagers come in to buy the stuff for home tattooing, then tried to blame her later when they all got blood poisoning. Different kinds of ink polluted our blood; I felt an odd solidarity with those kids, remembering the words others had scored on my skin for years. Tattooing yourself, perhaps, was a way of taking those names back. In any case, there was a sense that the ink was like oil, a reserve of energy I was drawing from the deep.

Recovery was trying to breathe underwater; resisting the urge of the quickening tide, striving for an island I couldn’t yet see.

(…What I miss most, maybe, is the driftwood intricacy, the beauty of the sternum in its gaunt, tripart sculpturing. Thinned to the bone, the body becomes elegiac somehow, an artefact of ebbing beauty…)

I think about beef and milk and I think about the bodies of cows and the way the light drips gold on their fields sometimes and how I’d like to curl up in some mossy grove and forget that all of this is happening. Sometimes I worry that my body is capable of making milk, making babies; its design is set up for this nourishing. Hélène Cixous insists women write ‘in white ink’ but I don’t want to be that plump and ripe, that giving. I want scarification, darkness, markings. I want Julia Kristeva’s black sun, an abyss that negates the smudge of identity.

I try to find loveliness in femininity, but my hands are full with hair barrettes, pencils, laxatives, lipstick—just so much material.

As Isabelle Meuret puts it, ‘starving in a world of plenty is a daring challenge’. Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. Recently, I logged onto my Facebook to find an old friend, a girl I’d known vaguely through an online recovery community, had died in hospital. Her heart just gave up in the night. People left consolatory messages on her wall; she was being written already into another existence. Another girl I used to know posts regular photos from her inpatient treatment. She’s very pretty but paper-thin, almost transparent in the flash of a camera. Tubes up her nose like she’s woven into the fabric of the institution, a flower with its sepals fading, drip-fed through stems that aren’t her own. She’s supposed to be at university. I think of Zelda Fitzgerald, of broken ballerinas. A third girl from the recovery forum covers herself in tattoos, challenging you to unlock the myriad stories of symbol. Someone I know in real life gets an orca tattoo in memory of her sea-loving grandfather; she says it helped to externalise the pain. My own body is a pool of inky potential; I cannot fathom its beginning and ending. I wish I could distil my experience into stamps of narrative, the way the tattoo-lovers did. I am always drawing on my face, only to wash the traces away. I must strive for something more permanent.

Recovery, Marya Hornbacher writes in her memoir Wasted,

comes in bits and pieces, and you stitch them together wherever they fit, and when you are done you hold yourself up and there are holes and you are a rag doll, invented, imperfect.

And yet you are all that you have, so you must be enough. There is no other way.

Every meal, every morsel that passes the lips, we tell ourselves: You are okay. You deserve this. Must everything be so earned? Still there is this girl underneath: the one that screams for her meagre dreams, her beautiful form; her starlight and skeletons, her sticks of celery. I try to bury her behind sheet after sheet of glass, lose her in shopfronts, the windows of cars and bathrooms; I daily crush out the bloat of her starched hyperbole, keeping the lines plain and simple. Watching others around me, I try to work out other ways of feeling full, of being free. There is an entry from 2009, scratched in a hand I barely recognise in the final page of a diary: ‘Maybe we are only the sum total of all our reflections’. I wonder what kind of sixteen-year-old wrote this, whether she is happy now and if that matters at all.