Corpuscles spit constantly from the idea of sleep so I begin to fear it. Blood in the morning, metallic taste, no sweetness left from the Corsodyl but we try. Bits of shared housing make their way into my art, particulate matters: the gunshots pop pop, just fireworks; the neighbourhood yaptastic chihuahua called Barry; the pyrotechnics of teenage boozing which take place at the end of my street. A fully red tracksuit, a purple tracksuit, a secret shop which sells brownies laced with weed. Brown paper parcels with rips in them. Which Christmas ruined everything. Clicking dream materials of remembering scent, coming out with bundles of abundant orchids. Impossible for them to flourish here. Yet I coruscate brightly as if after surgery. If I could work with the wallpaper swirls in my dreams I would

put them into comets, then sentences.

Explosives can fire in space. They can’t disperse a tornado. In the hands of amateurs, the fireworks emit more smoke than is desirable. I go out to the smoke-laced cold and see a glow belonging to the moment I want. It’s over there. It’s so close.

Tomorrow’s a needle in my arm.

Tinnitus is the sound of the universe.

It’s almost autumn and I can’t stop listening to The Corrs. Something ringing in the falling rain a leaf-lorn runaway, never gonna stop falling, wish I could play the strings and not cry over a snapped shoelace that Saturday, wish I could never need name this. A fresh nostalgia for Flash player, a bad new year, kneeling in the car dirt of roadsides to fix my bike, the air all gone out of each tyre it’s tiring to be here / wish I could change. Not into other people but into the person I was, rosy-fingered sleepless rolling cinnamon skins and talking on the internet while in the other town this guy throws a mattress out of a window. If memory serves to fall out with it. Black lace and white corduroy out to the woods I’m happiest on the hill where I see this deer, evidently a teenage stag and I’m calling angel androgynies the very next stray. Fucked up salads of affect, afraid to go outside. Emma says everyone’s a poet. You just go.

Crying in the cobblers for other omens.

Girls in the nineties with strands of dark hair, box-dyed. The electricity all gone out. I was supposed to be planning a workshop, writing a lecture. The universe owns me, doesn’t owe me.

Across oceans of static, watching you typing…

I cycled past the cathedral and saw the sycamores blush orange as if in real-time metabolising their chlorophyll before me. I google the phrase ‘fall splendour’ in guilty luxuriance. A man on my street pisses against the wall, daylight screams; he pisses for so long I think he will disintegrate in dumb liquid gold. Can’t concentrate on this Zoom call. I’m missing something real of the days before me. Girl in old man bar is singing a ballad. Can you drink a black hole if you can’t drink a Guinness? Colin says Brian says you’d have to suck through a straw at the speed of light. Girl in old man bar is wearing tartan, a velvet headband, recently expired lipstick. I like her.

Singing Eliza Carthy, singing Amen Dunes…

I always want autumn too early and pine for spring. Trillions of magazines tell me it’s not cool having holes in my tights. It’s not cool having ragged cuticles.

Ten years of sleazy beauty.

A paintbrush yellowing in sordid water.

Forever down Cathcart Road.

Incurable bed mornings of limb ache and long illness, it’s fine like to say it’s totes, bring myself coffee in bed and emails filling me with autumn leaves and the fly infestation fed upon fruit and air…a red car rolling backwards up the street…

It used to be so easy to write these like it never mattered to write at all. The sky is still whey and there are new routes to get to the same old temples. I swirl my tongue in the google doc long enough to know how I’d touch you; the hopescape bristles with city pollution. My friends have been to Greece and Bali, the Hebrides. I have been to Edinburgh for work. Come down the wrong side of the hill among gorse and scramble, the rocks coming loose and my heart gone trash-eating in the nights of bad sleep again, all again, falling awake with the light on, spilled ink in my sheets. I met the same America on Netflix checking my brain, my gag reflex.

I heard the blood blister in that guitar riff and it was like vomiting behind the shopping mall in Kilmarnock, drunk on bus wine and the Alice in Chains of my arteries…you awake, say the word clavicle, touch my spine…

The Corrs – Breathless

Alice in Chains – Tears

Hand Habits – No Difference

Beth Orton – Weather Alive

Belle & Sebastian – Working Boy in New York City

Sharon Van Etten – Darkness Fades

Baths – Tropical Laurel

Doja Cat – Love to Dream

Adios Nervosa – cloudcover

Drugdealer – Madison

Thee Oh Sees – Chem-Farmer

The 1975 – Part of the Band

June11 – Who is Still Dreaming?

Regina Spektor – Loveology

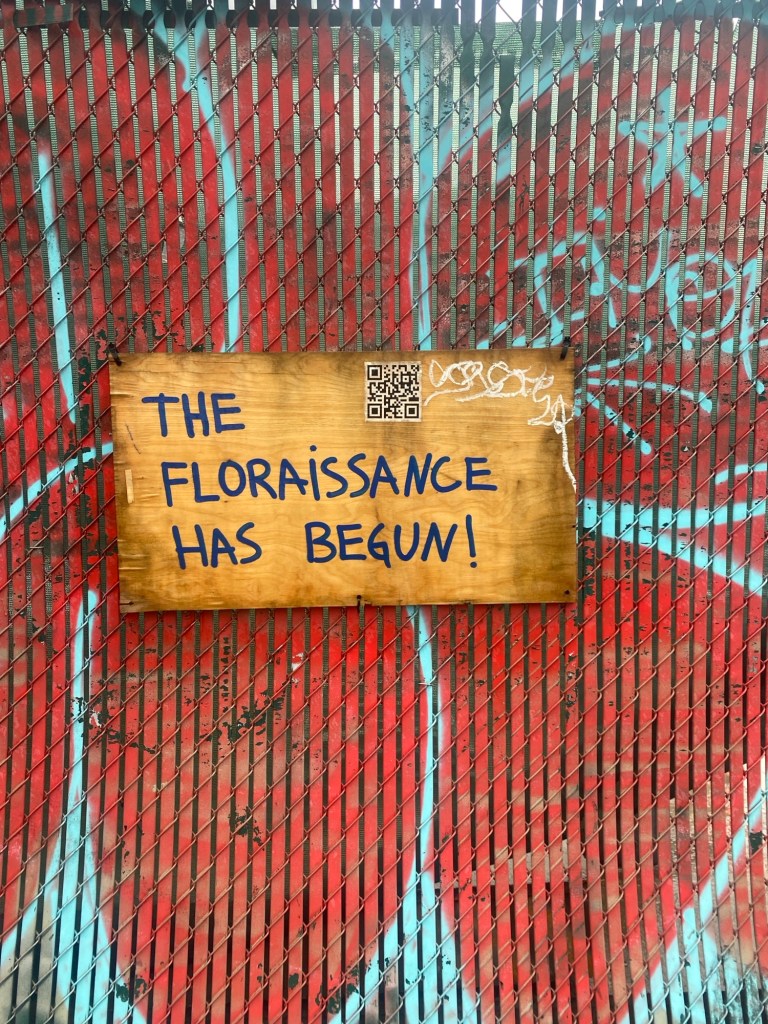

Last week I taught a seminar and workshop at the University of Glasgow’s Summer School: Urban Arcadia: Mythologies of the Mall. We explored how malls represent liminal spaces of urbanism and suburbia, public and private, the civic and surveillance. We reflected on the decline of malls in recent years, on the deadmalls archive project, on malls as institutions, infrastructures and emblematic locales of capitalism. I once wrote a phenomenology of my local mall, a shopping centre in Ayr, the site of teenage loitering, toil and trouble. I asked the students to write manifestos or plans towards new malls: public sites built into or out of a failing mall building. The more I write mall, the more I fall into it. The idea of plenitude. One student said malls are so prevalent in post-apocalyptic fiction because that’s where the resources are pooled. It’s only natural that when capital eats itself we go back to its crumbling temples to eat. Malls are for raiding, free-running, skating, squatting, paying disrespect to statuesque disgrace of billionaires, wishing in fountains, abolishing, raving, growing plants in greenhouses. Malls with solar panels, malls with turbines, malls with open canteens, malls where you take what you like. I want malls to metabolise the brilliance of dreaming the billioning of a generous elsewhere that yes could be ours, not like in adverts but actually in our hands, sticky with bricks and mortar and molten pennies the fountains spat back as lithium rainbows in the battery acid of plurality, nothing pristine, our shattering. It’s so infinitely worthless, warm and deplorable. The lyric I is a mallwalker. All of them. Open doors.

I’ve written about malls before in fiction and poetry. See ‘Mallwalkers’ and Rainbow Arcadia.

Suggested exercise:

Mall Regeneration

You have been tasked with reviving a so-called dead mall in your local town or city. The budget is limitless! In pairs, come up with a manifesto for how you would rebuild the mall or put it to new uses. You might want to share the different contexts of how retail works in your local area and think about a ‘solution’ that works for both of you. What values do you find important in urban architecture? How should public space be used in the twenty-first century and beyond? Is this mall just for human people or other creatures? What would the mall need to serve, withstand or endure?

You can write this as a list or mini essay.

Late October, Cycled home in my t-shirt, thru the industrial estate and beyond. you and I remember well the opening sequence, credits to all those sly cartoons who lived in colours not of their own choosing. what I’m trying to say is the warmth comes not explicable from crisis, to say ‘i was warmed by crisis’ seems wrong, and yet as I walk in a light denim jacket purchased on the day of the kenmure raid, people are still debating who was the OG lady of sadcore, adele or lana del rey? there are two versions of the skins episode where cassie escapes to new york and she runs through an impossibly empty city: one which plays an Adele track and another which plays ‘My Town, My City’ by an unidentified artist which now seems relegated to the half played halls of ancient youtube history, yet also the chorus that would seem to claim for its singer something of a belonging in cold despair. in memory the piano begins when she bites into the apple and starts crying but this could have happened in any dimension, especially considering every time i bite into an apple now my eyes smart, crunching into a moment straight from chris marker and sugar brushed with what he doesn’t know, bright red, i mean ordinary feminine pain, or like, the year 2007 in bristol. i didn’t know what UK garage classics were until i keyed my first car or like buzzed myself athletically through the other door where i would be welcomed as a stranger to victorian milk and honey, reversing the version where you can’t wear that necklace for it has bumped against her sternum and now something of a soul is dead. my friend died but ever since july i have compulsively worn purple. when i get synaesthesia it’s usually for songs, words, general emotions that in relation make up grids or curlicues surprisingly happy to coexist, like if i draw a lilac spiral where your name once is, i feel better, i feel better. it’s a schoolgirl trick of the selfsame like writing out names in our jotters, yours or mine, walking the perambulator back to the moon where exhausted mothers are calling their mothers to war. we benefited from working tax credits and educational maintenance allowance, i asked friends born with particular chromosomes to buy me yorkie bars, i remember the feel of warm summer tar against my skull better than i recall my first fuck tho a kiss was easy, it was like pulling another fish through a big comma soaked in bourbon and the bright lights were on and everyone watching? sometimes i have to go out a room to remember something like what are you doing here, now i have to walk around to even get writing or find eloquence in pavement slopes. where i live now you smell hops on mondays and thursdays the cats are not ginger, i let them nuzzle against my leg in exchange for a purr. tonight there were electrical failures in the library so i decided not to imagine my evening as a series of blocks defined by the hours locked upon flat surfaces. this house has a shed! if i listened to anything it was to the street lights twinkle as mushrooms do when stamped on, baby screeches, we come home with medical certificates and iron deficiencies with mouthfuls of words about aurora borealis and sandstone. thru the periurban and elderberry. i create a sequence and it forges a colour for itself, can’t be changed. i’m wearing a white t-shirt and it’s late in the autumn and i’m telling you this because the sky is purple, it’s 16 degrees and i want to change

If the portal is a smiley you want, abstracted, I already

am the same. Await your reply if we are alternative time

zones, your train was late and the wifi shaky is only

another ‘trembling structure’ in the words of John

Wieners. It wasn’t smiley it was pure mad HIYA smiley,

aslant on the concrete childhood where once I lay down

and later tried to make this theory. Lie flat. All the

horses lie down in protest of symbolism. That I write

anthropomorphically is only because most days I am

more like a fox and stealthily will steal your garden

gnomes to think they are chickens and the most

perverse fox I turn vegetarian, asking the gnomes what

happens down the drains and they say ask the trolls.

But this is why I left twitter in the year 2030, released

a thousand marbles in the weft of the sun’s coming

too close for comfort, organised my floating children to

clearfix the element, old and browserly on your blog.

Shine brightly with flashes of light. Will I fuck. That feeling

when you miss someone but somewhere to know they are

there for you, making bread or like, conserving energy.

You should buy a firm mattress if you want to lie

on your back and tell me the stars were good, what else, like

how could you put that in a past tense where the stars are

still coming, £10.99, they are light years towards us and to think

of when the stars are come is delicious, becoming this

drunk at the splendid omen, lavishly served. Inebriate

starlight / a laced pony / liquored with three sheets

to the wind and call you beauty. Hold us up.

Bubble write most of the film, asleep

means only to dream in the house / your birth.

All the drunk horses are sparkling, swear it.

Ariana Reines has this poem called ‘Glasgow’ that features the lines: ‘We wanted life now / But not “real” life / We wanted the exact science / Fiction / We were living in / We didn’t want it’. I keep thinking that just living is so often this contradiction, or Eileen Myles declaring ‘a poem says I want’ and knowing how right they are, Ariana and Eileen, and where are we when we come to this knowing. I mean, why does such philosophising happen in a poem called ‘Glasgow’. It’s clearly set in Finnieston, I mean there’s ‘Berkeley Street’ and ‘the Sandyford / Hotel’. I wonder if Ariana knows the pawn shop is not really a pawn shop, or if she ever bought poppers or condoms or candy from the 24hr place near the Hidden Lane. Here I am with americanisms again. I mean I wonder if my idea of Ariana would bother nipping from her hotel room to replenish the tobacco she ran out of. Would she bauk at UK prices? Does she even smoke? My idea is always a she here and she likes to go into contingent nightclubs more than the store. It’s what we give away. Finnieston used to be not-expensive. I once wrote a poem called ‘Finnieston’, I was younger, it was kind of bad. It was about this release you get from finishing something, crossing a bridge. I used to go through the park to get to my friend’s house or the 78 and every other time the shops and bars along the strip would be different. A kind of fantasy district, reinventing itself coolly around me. Someone in the world is having the gentrification blues and listening to Courtney Barnett’s ‘Depreston’. Like sometimes I just sit and think, oh how about that whimsy! It’s hers, but you can borrow it with a jangle tone. Bottle it like Tango. And we shriek the world percolator into the dark, fizzing stars of etcetera. In the morning order lattes. Goodness sake is this what it is to write now, I love it.

Slowly, slowly. I measure out my life in Scotrail tickets. Walking around cities and trying to carve them into a poem, I mean that’s not what any of us are doing but it happens. Just comes, like orange. This month I spent a lot of time outside of my usual quadratic existence; I didn’t have to count the change in the leaves, there was already so much that was different. Things sped up. Once we live in it, do we not want it? Orange curls at the edge. That feels like a worded conundrum of someone who’s spent awhile on the streets, in some capacity. Not necessarily without home. I was counting the crisp packets from my perch on Uni Avenue, overlooking the construction works. Is it that nothing online is real as well, if you can have as real a nothing as the something of life? We don’t want this and yet it’s what we built, what we live in; we crave the ‘outside’ still, as though it were possible. It’s all in process. The station goes on a real bright tangent.

I like to just say, Ariana Reines wrote a poem about Glasgow. I feel honoured on behalf of my adopted city. It ends ‘Way out’. This consideration of exits, secret passages under the Clyde, riding bridge-wise towards the April I had to trudge hungover from tea-room to tea-room, listening. Hey. I saw Ariana read last summer at the Poetry Club (thanks Colin!), I think she was wearing a white dress and she said she might menstruate at any minute, she said something beautiful about the sun and the moon, synchronicity, and it was exactly what we needed. I mean her sultry voice filling the room, release. I mean I felt validated in my cramps and misery.

Tiny red spots appear like a migraine painting my belly.

There’s the rain now. The rain broke the heatwave. Is it Cetirizine causing my headache, this marathon pain like a marble rolling between my temples? When I go see Iceage play Broadcast, the room is sweltering. There’s a general jostling and adoration of bodies, like this guy is Scandinavian divine and just one lick of his sweat would cure your ills. The ills of a lack of a life. When we are living between. Catch It. I like to use the phrase ‘out west’ as a general euphemism for escape. Like sorry I gotta go, there’s a meeting out west, something happening out west, I’m owed time back west like the sky’s owed snow. A Sand Book (Reines, 2019). If you close it too fast the grains fall out. As though I could make of Kelvingrove the savanna that takes us out of my dreams. In the novella I wrote last year, there’s a whole childhood set there. It’s somewhere in America that you’d find in a song, but it crackles with violence and the fat-spitting fry ups of diners. Or does it at all. Who did she wait for.

Cherubic sleeping face.

Sketches of rooms.

Seafoam teal & mustard yellow.

There was a whole Monday morning in London I filled alone. It was strange to come close to a cacophony of accents you only usually heard on the telly, the city accenting its vowels to deliver things quickly. And yet we’d roll like beads in jelly, very slowly towards ourselves. I walked along Regent’s Canal with the flowers spilling out around me, cyclists slipping past and women smoking fags from canal boats, smiling their air of propriety. ‘Way out’ I could not go here. I knew if I stuck to the water it would all be fine, follow the line that was not the Tube. In London Field Park, someone had chalked XR slogans everywhere. ‘Rise Up’ was the order of the day in green and sorbet yellow. I tried to recount what had happened in a slim black notebook; I sat there on a bench for an hour and a half, just writing. A man asked me if he’d seen ‘a gaggle of unruly school kids’ come past. I answered in negative. There was only the other man on his phone, securing deals, pacing. Hot desking now meant you’d conduct interviews with iPads in parks, squinting against the light. I saw that also. I was at a gig where the band had a song about hot-desking. The drummer was also a vocalist, equalling my dilemma in the park: how to co-ordinate melody and rhythm. The runners ran past. Rucksack cutting into my shoulders. The air thickened black soot in my lungs but the buildings were lovely. I nearly left my orange socks behind. They weren’t even mine, originally.

When the sun sets on Finnieston, you see it spill syrupy gold and pinks, dramatic skies up Argyll Street.

Rise Up. [?]

That tree was an ash, the other a sycamore. I found myself in St Pancras Old Churchyard, staring. Supposedly Mary and Percy Shelley would cavort here.

I could drink coffee and be utterly happy, in a New York poet kinda way. Better to be the one who’d been to New York. Just to say this happened, that happened, I like it or not. We live this. There is something we want to get out of. Taking the subway in endless circles. Glassware exotica rimmed with sugar-salt.

All the aloe vera on stage was infinite juice.

Why the lack of seagulls here. Isn’t the Thames a tidal river?

People come to the gardens to make phone calls in London. Everyone exists in the cellular orbit of this extra life, the telephonic aura that follows them. Can you call my extension. She sits there with sushi on her lap. “Elaine’s not having IVF anymore.” I live off M&S egg and cress sandwiches for days, it’s good. Soon I would watch the land sweep back the sea from the train, heading north, east-coast. There was all this chewed-up rhubarb, but I sat there regardless. The birds were so tiny and tame, with their injured wings, polluted fashions.

Casual nymph mode: Fairy Pools of Skye and a swim. The car ride singing Joni while the hills just spread their green; we are so deliciously far from Paris. I lie awake with the skylight, listening.

In Dumfries I eat vegan blueberry pie at the start of the month, we talk about American politics. I’d been watching that Years and Years programme and freaking out on a casual basis. When it’s the eve of 2029 and the grandmother makes a speech about the utopianism of thirty years prior, 1999, how we thought we’d sussed it. That got to me, because for the first time so clearly I saw my own lifespan as part of this history. I remember the millennium new year also, of course I do: my hair was crimped for the occasion, I ate pringles and kept my bunny close. Blonde self red-eyed pre-digital. I played Game Boy in lieu of karaoke; it was the latest I’d stayed up in my life. I had nothing to sing; soon I’d be seven. The exact science fiction of this scenario, Years and Years playing out the extension of what was already in motion, terrified because it was imminent, believable, situated here in front of us, the domestic reality of interconnection. But in a way, it felt very English and I realised that was different. Glasgow has its own science fiction and maybe it’s just this or better politics or something more solid that doesn’t result to a haze. I think of everyone jostling at the hothouse gigs. Something we can’t hold still, glass bottle of cider from your bag that might burst. I’m happy. That blueberry pie was so good. I didn’t even care about radiation.

In Sam Riviere’s poem ‘american heaven’ (Kim Kardashian’s Marriage, 2015), ‘the level of heaven we develop within us / is the level it was possible to imagine / of the assorted early 80s, on earth’. Keep reading these articles about local bands sporting eighties outfits, drinking in the same old man pub as the previous feature. A general vacuity coming on like a front, but what can we do, lacking the ‘facsimile architecture’ (Riviere) of a more american heaven? The pie was served without ice cream of course, that was the point. No dairy. I keep five different diaries this month, split across documents, notebooks, assortments of train tickets. Creamy excess of this prose. My purse empties a cascade of rectangular orange. I throw around terms like ‘post-vaporwave poetics’ and mean them sincerely. What if we had to incubate our own heaven first? Lana Del Rey: ‘You’re my religion / You’re how I’m living’ (Honeymoon, 2015). 2015 was a good year for heaven. We hadn’t had 2016 yet; we were almost teenage of a nation. Riot, right?

London is all facsimile architecture. There’s this slime in the canal that’s thicker than lawn turf, extra real. I can’t stop thinking about that. Algaeic esplanade trapping the fishes. Can’t stop listening to that King Gizzard song, the refrain that’s like ‘I’ve let them swum’ and maybe that’s minimal ethics for the anthropocene. You just perform a minor twist in grammar, you make that the way you live:

Our human responsibility can therefore be described as a form of experiential, corporeal and affective “worlding” in which we produce (knowledge about) the world, seen as a set of relations and tasks. This may involve relating responsibly to other humans, but also to nonhuman beings and processes, including some extremely tiny and extremely complex or even abstract ones (microbes, clouds, climate, global warming). Taking responsibility for something we cannot see is not easy.

(Zylinska, Minimal Ethics for the Anthropocene, p. 97)

You could say the hypothetical fishies. We can fish for other things! Sentiment, care! Wholesome lyrics leading towards charismatic solos. Some kind of upbeat. Magikarp! so nothing happened. Things beneath the orange-green we cannot see. How are we supposed to care for slime? That song is a world, makes over the world. I think of powder and glow, contour, blend, gloss — a process of ‘make up’ or making up that structures Kim Kardashian’s Marriage (from ‘Primer’ to ‘Gloss’), that fashions a map of the face, the frontal location for ethical relations. In the library, the girl beside me writes about South Korean politics while listening to ASMR makeup videos. We all have our imminent fictions; not ‘real’ life, but it’s not always science.

Sometimes I want algaeic to fall into angelic, both pertaining to light.

We didn’t want to live in the life we made to live in where we might want.

To walk down the Royal Mile in the rain, bumping tourists, slowly crunching into an apple and letting your hair down into noise, a sort of soundcloud rap of near-distant, muted present. The apple was green and particularly sweet, low volume, like something discovered in the pockets of a pair of jeans you borrowed.

I’m awake at four am again. It doesn’t seem to matter so much. The gulls are morning/mocking. Later I’ll be at the kitchen table, chewing oatcakes with the window open. Reading Peter Sloterdijk’s Foams: Spheres Volume III. Is extinction one kind of what he calls ‘semantic antibodies’? Who is trying to excise that from the conversation?

Mostly I dwell in vicarious haircuts.

There’s a thought after the thought.

Drink whisky in the park, read fiction.

Your pinstripes lack a fly but still.

We fall asleep five times watching this Will Smith documentary about the planet. We never finish an episode. It seemed to stage the incoherence of a Hollywood sublime set to reverie’s overdose, but only the scene where he’s playing with his dogs in the garden remains. Sepia, sleep better. I slept deeper than a rock at the bottom of everything. June still feels like a dream.

I only want to get home to write the day. Every entry begins, another sweltering…

That’s what…good is?

~

Slowdive – Sugar for the Pill (Avalon Emerson’s Gilded Escalation remix)

The 1975 — The 1975 feat. Greta Thunberg

Mark Hollis — The Daily Planet

Grouper — Invisible

Laurel Halo — Out

Joni Mitchell — Rainy Night House

Devendra Banhart — Kantori Ongaku

Joanna Sternberg — For You

RF Shannon — Angeline

Fionn Regan — Collar of Fur

Thee Oh Sees — Moon Bog

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard — Fishing for Fishies

(Sandy) Alex G — Hope

Slow Hollows — Selling Flowers

Frog — Bones

DIIV — Skin Game

Ibeyi — River

Blood Orange, Tori y Moi — Dark & Handsome

Aisha Devi — The Favor of Fire

How to Dress Well — Nonkilling 6 | Hunger

Organ Tapes — Springfield

black midi — Western

Bon Iver — Faith

TOPS — Sleeptalker

Let’s Eat Grandma — Salt Lakes

Carla dal Forno — Took a Long Time

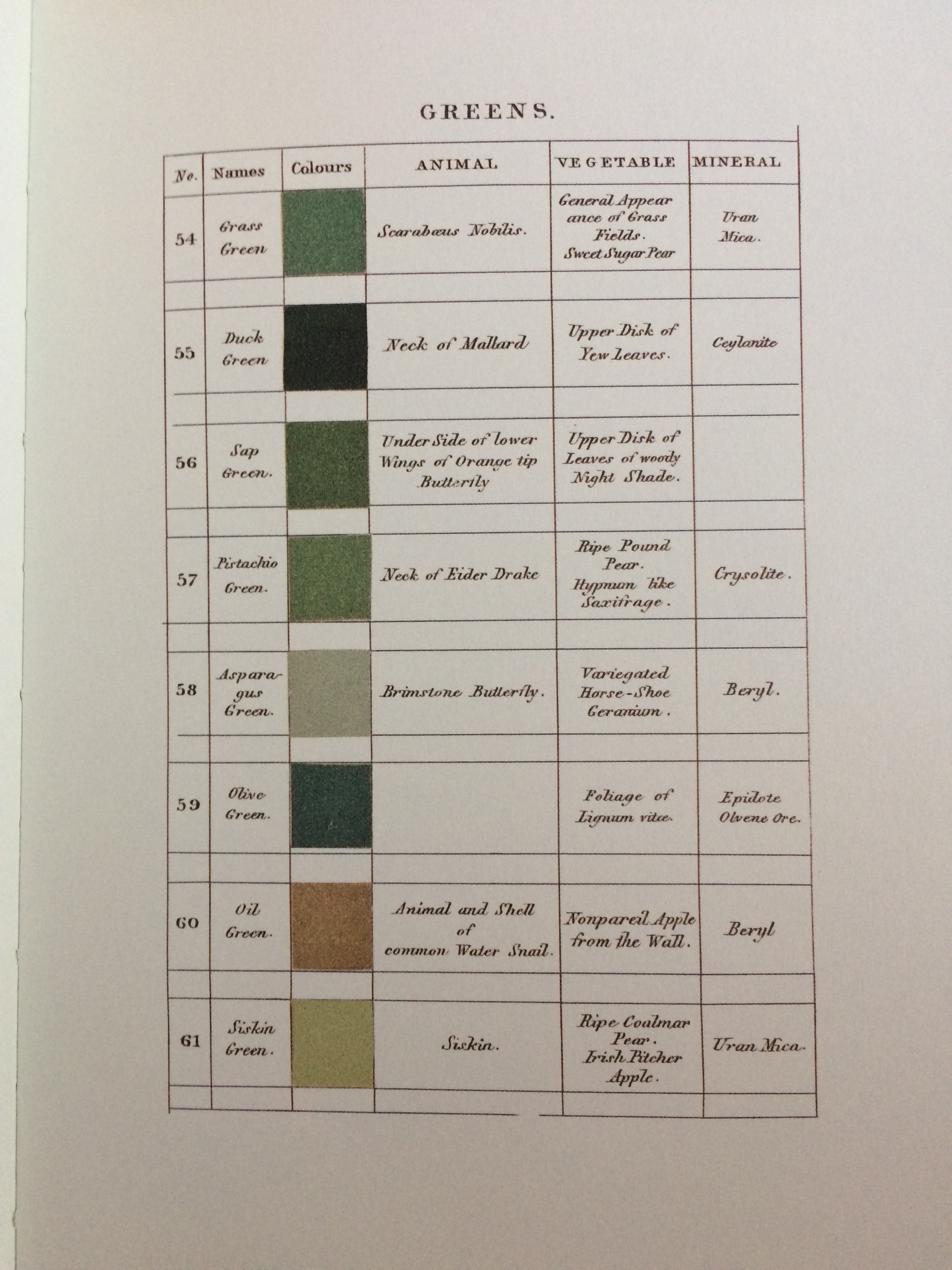

Lately I’ve been haunted by a couple of lines by James Schuyler: ‘In the sky a gray thought / ponders on three kinds of green’ (‘A Gray Thought’). I can’t work out what kinds of green he means. Funny how the trees of London still have their leaves, mostly, and how the city keeps its own climate. Sunk in a basin. Schuyler names the source of the greens: the ‘tattered heart-shapes / on a Persian shrub’, ‘pale Paris green’ of lichens, ‘growing on another time scale’, and finally ‘another green, a dark thick green / to face the winter, laid in layers on / the spruce and balsam’. A grey thought to match the greyer sky. The sky has been grey in my life for weeks, it came from Glasgow and it came from England; I saw it break slightly over the midlands, a sort of bellini sunset tinged with pain. I just wanted it to fizz and spill over. I saw my own skin bloom a sort of insomnia grey, a vaguely lunar sheen. Schuyler’s greens describe a luxury of transition, pulling back the beaded curtains of winter and finding your fingers snagged on pearls of ice.

There is a presence here, and a space for mortality that starts to unfold like the slow crescendo of a pedal, held on the upright piano of childhood, whose acoustics promise the full afternoons of a nestlike bedroom. Which is to say, everything here. Protection. Which is to say, where every dust molecule seems to glow with us, which makes us multiple. A commodious boredom that opens such worlds as otherness is made of, ageing. Annie Ernaux in The Years (2008):

During that summer of 1980, her youth seems to her an endless light-filled space whose every corner she occupies. She embraces it whole with the eyes of the present and discerns nothing specific. That this world is now behind her is a shock. This year, for the first time, she seized the terrible meaning of the phrase I have only one life.

There is this life we are supposed to be living, we are still working out the formula for. And yet the life goes on around us, propels through us. It happens all the while we exist, forgetting. It is something about a living room and the satisfying crunch of aluminium and the echo chamber of people in their twenties still playing Never Have I Ever. And the shriek and the smoke and the lights outside, reflective laughter.

The many types of grey we can hardly imagine, which exist in friction with the gild of youth. He shows me the birthday painting hung by his bedside. It is blue and green, with miasmatic tangles of black and gold, like somebody tried to draw islands in the sky with lariat shapes. I look for a roar as I walk, as though something in my ears could make the ground tremble. The air is heavy, a new thick cold that is tricky to breathe in. It requires the clever opening of lungs. I stow cigarettes from Shanghai in my purse. My Nan says she gets lost in the city centre. She gets lost in the town. She looks around and suddenly nothing is familiar. She has lived here for years and years and yet. It is the day-to-night transition of a video game, it is the virtuality of reality, inwardly filtered. She sucks industrial-strength Trebor mints and something of that scent emits many anonymous thoughts in negative. How many worlds in one life do we count behind us?

There is something decidedly Scottish about singing the greys. A jarring or blur of opacity. We self-deprecate, make transparent the anxiety. There is the grey of concrete, breezeblock, pregnant skies delivering their stillborn rain. Grey of granite and flint, grey of mist over shore; grey of sea and urban personality. We splash green and blue against the grey, call it rural. Call it a thought. Call out of context. Lustreless hour of ash and in winter, my father lighting the fire. In London they caramelise peanuts in the crowded streets, and paint their buildings with the shiniest glass. It is all within a movie. My brother walks around, eyeing the landmarks and shopfronts fondly, saying ‘London is so…quaint’. He means London is so London. I stray from the word hyperreal because I know this pertains to what is glitz and commercial only. It does not include the entirety of suburb and district; it is not a commuter’s observation. Deliciously, it is sort of a tourist’s browsing gaze. Everything dematerialises: I get around by flipping my card, contactless, over the ticket gates. There is so much to see we forget to eat. It is not so dissimilar to hours spent out in the country, cruising the greens of scenery, looking for something and nothing in particular. Losing ourselves, or looking for that delectable point of loss. As Timothy Morton puts it, in Ecology Without Nature (2007), we ‘consume the wilderness’. I am anxious about this consuming, I want it to be deep and true, I want the dark green forest inside me. I want the hills. I’m scared of this endless infrastructure.

Some prefer a world in process. The greys reveal and conceal. The forest itself pertains to disturbance, it is another form of remaking. Here and there the fog.

In ‘A Vermont Diary’, it’s early November and Schuyler takes a walk past waterfalls, creek flats, ‘a rank harvest of sere thistles’. He notes the continuing green of the ferns in the woods, the apple trees still bearing their fruit despite winter. Our craving for forest, perhaps, is a primal craving for protection of youth, fertility, sameness. But I look for it still, life, splashed on the side of buildings. It has to exist here. I look up, and up; I j-walk through endlessly aggressive traffic. What is it to say, as T. S. Eliot’s speaker in The Waste Land (1922) does, ‘Winter kept us warm’?

Like so many others, in varying degrees, I walk through the streets in search of warmth.

Lisa Robertson, in Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft Architecture (2003), writes of the inflections of the corporeal city:

Architectural skin, with its varieties of ornament, was specifically inflected with the role of representing ways of daily living, gestural difference and plenitude. Superficies, whether woven, pigmented, glazed, plastered or carved, received and are formed from contingent gesture. Skins express gorgeous corporal transience. Ornament is the decoration of mortality.

So with every gorgeous idiosyncrasy, the flourish of plaster, stone or paint, we detect an age. A supplement to the yes-here fact of living. I dwell awhile in Tavistock Square and do not know what I am supposed to do. So Virginia Woolf whirled around, internally writing her novels here. There was a great blossoming of virtual narrative, and so where are those sentences now — might I look for them as auratic streams in the air, or have they regenerated as cells in leaves. There are so many sycamores to kick on the grass. There was a bomb. A monument. Thought comes over, softly, softly. I take pictures of the residue yellows, which seem to embody a sort of fortuity, sprawl of triangular pattern, for what I cannot predict. Men come in trucks to sweep these leaves, and nobody questions why. The park is a luminous geometry.

I worry the grey into a kind of glass. The cloud is all mousseline. If we could make of the weather an appropriate luxury, the one that is wanted, the one that serves. In The Toy Catalogue (1988), Sandra Petrignani remembers the pleasure of marbles, ‘holding lots of them between your hands and listening to the music they made cracking against each other’. She also says, ‘If God exists, he is round like a marble’. The kind of perfection that begs to be spherical. I think of that line from Sylvia Plath’s poem ‘Daddy’ (1960): ‘Marble-heavy, a bag full of God’. So this could be the marble of a headstone but it is more likely the childhood bag full of marbles, clacking quite serenely against one another in the weight of a skirt pocket. Here I am, smoothing my memories to a sheen. I have a cousin who takes photographs of forests refracted through crystal balls. I suppose they capture a momentary world contained, the miniaturising of Earth, that human desire to clasp in your hand what is utterly beautiful and resists the ease of three-dimensional thought. How else could I recreate these trees, this breeze, the iridescent play of the August light?

I like the crystal ball effect for its implications of magicking scene. One of my favourite Schuyler poems is ‘The Crystal Lithium’ (1972), which implies faceting, narcosis, dreams. The poem begins with ‘The smell of snow’, it empties the air, its long lines make every description so good and clear you want to gulp it; but you can’t because it is scenery just happening, it is the drapery of event which occurs for its own pleasure, always slipping just out of human grasp. The pleasure is just laying out the noticing, ‘The sky empties itself to a colour, there, where yesterday’s puddle / Offers its hospitality to people-trash and nature-trash in tans and silvers’. And Schuyler has time for the miniatures, glimpses, fleeting dramas. My cousin’s crystal ball photographs are perhaps a symptom of our longing for other modes of vision. They are, in a sense, versions of miniature:

“Miniature thinking” moves the daydreaming of the imagination beyond the binary division that discriminates large from small. These two opposing realms become interconnected in a spatial dialectic that merges the mammoth with the tiny, collapsing the sharp division between these two spheres.

(Sheenagh Pietrobruno, ‘Technology and its miniature: the photograph’)

Miniaturising involves moving between spheres. How do we do this, when a sphere is by necessity self-contained, perhaps impenetrable? I think of what happens when I smash thumbs into my eyes and see all those sparkling phosphenes, and when opened again there is a temporary tunnelling of sight — making a visionary dome. Or walking through the park at night and the way the darkness is a slow unfurling, an adjustment. For a short while I am in a paperweight lined with velvet dark, where only bike lights and stars permit my vision, in pools that blur in silver and red. The feeling is not Christmassy, as such colours imply. It is more like Mary of Silence, dipping her warm-blooded finger into a lake of mercury. I look into the night, I try to get a hold on things. On you. The vastness of the forest, of the park, betrays a greater sensation that blurs the sense between zones. I cannot see faces, cannot discern. So there is an opening, so there is an inward softening. What is this signal of my chest always hurting? What might be shutting down, what is activated? I follow the trail of his smoke and try not to speak; when my phone rings it is always on silent.

It becomes increasingly clear that I am looking for some sort of portal. The month continues, it can hardly contain. I think of the towns and cities that remain inside us when we speak, even the ones we leave behind. Whispering for what would take us elsewhere.

Write things like, ‘walked home with joy, chest ache, etc’.

They start selling Christmas trees in the street at last, and I love the sharp sweet scent of the needles.

There is a sense of wanting a totality of gratitude, wanting the world’s sphere which would bounce back images from glossier sides, and so fold this humble subject within such glass as could screen a century. Where I fall asleep mid-sentence, the handwriting of my diary slurs into a line, bleeds in small pools at the bottom of the page. These pools resemble the furry black bodies of spiders, whose legs have been severed. A word that could not crawl across the white. I try to write spellbooks, write endlessly of rain. Who has clipped the legs of my spiders? I am not sure if the spells I want should perform a banishing or a summoning. The flight of this month. The icy winds of other cities.

The uncertain ice of my bedroom: ‘tshirts and dresses / spiders in corners of our windows / making fun of our fear of the dark’ (Katie Dey, ‘fear pts 1 & 2’). Feeling scorned by our own arachnid thoughts, which do not fit the gendered ease of a garmented quotidian, the one we are all supposed to perform. I shrug off the dusk and try out the dark, I love the nocturnal for its solitude: its absolute lack of demand, its closed response.

In the afternoon, sorting through the month’s debris. A whole array of orange tickets, scored with ticks. The worry is that he’ll say something. The dust mites crawl up the stairs as I speak between realms. This library silence which no-one sweeps. There is the cinema eventually, present to itself. I see her in the revolving glass doors and she is a splicing of me. Facebook keeps insisting on memories. People ask, ‘What are you doing for Christmas?’ Wildfires sweep across California and I want to say, Dude where are you? and for once know exactly who I am talking to. I want to work.

On the train I wanted a Tennents, I wanted fresh air and a paradox cigarette. They kept announcing atrocities on the line.

She talks in loops and loses her interest. She gives up on her pills, which gather dust in the cupboard among effervescent Vitamin C tablets and seven ripe tomatoes, still on the vine.

Every station unfurls with the logic of litany, and is said again and again. Somewhere like Coventry, Warrington. This is the slow train, the cheap train. It is not the sleep train.

In Garnethill, there is a very specific tree in blossom; utterly indifferent to the fading season. It has all these little white flowers like tokens. I remember last December, walking around here, everything adorned with ice. Fractal simplicity of reflective beauty. Draw these silver intimations around who I was. An Instagram story, a deliberate, temporary placement. Lisa Robertson on the skin of an architectural ornament: well isn’t the rime a skin as well; well isn’t it pretty, porcelain, glitter? Name yourself into the lovely, lonesome days. Cordiality matters. I did not slip and fall as I walked. One day the flowers will fall like paper, and then it will snow.

It will snow in sequins, symbols.

Our generation are beautiful and flaky. Avatars in miniature, never quite stable. Prone to fall.

Maybe there isn’t a spell to prevent that, and so I learn to love suspense. And the seasons, even as they glitch unseasonable in the screen or the skin of each other. Winter written at the brink of my fingers, just enough cold to almost touch. You cannot weave with frost, it performs its own Coleridgean ministry. Anna takes my hands and says they are cold. She is warm with her internal, Scandinavian thermos. Through winter, my skin will stay sad like the amethysts, begging for February. Every compression makes coy the flesh of a bruise; the moon retreats.

I mix a little portion of ice with the mist of my drink. It is okay to clink and collect this feeling, glass as glass, the sheen of your eyes which struggle with light. A more marmoreal thinking, a headache clearing; missing the closed loop of waitressing. Blow into nowhere a set of new bubbles, read more…, expect to lose and refrain. Smile at what’s left of my youth at the station. This too is okay. Suddenly I see nothing specific; it is all clarity for the sake of itself, and it means nothing but time.

Paint my eyes a deep viridian, wish for the murmur of Douglas firs, call a friend.

~

Katie Dey – fear pts 1 &2 (fear of the dark / fear of the light)

Oneohtrix Point Never ft. Alex G – Babylon

Grouper – Clearing

Yves Tumor, James K – Licking an Orchid

Daughters – Less Sex

Devi McCallion and Katie Dey – No One’s in Control

Robert Sotelo – Forever Land

Mount Kimbie – Carbonated

Free Love – Et Encore

Deerhunter – Death in Midsummer

Sun Kil Moon – Rock ‘n’ roll Singer

Noname – Self

Aphex Twin – Nanou2

Martyn Bennett – Wedding

Nick Drake – Milk and Honey

Songs, Ohia – Being in Love

Neil Young – The Needle and the Damage Done

I always have this sensation, descending the steps at Edinburgh’s Waverley Station, of narratives colliding. It’s a kind of acute deja vu, where several selves are pelting it down for the last train, or gliding idly at the end point of an evening, not quite ready for the journey home. The version that is me glows inwardly translucent, lets in the early morning light, as though she might photosynthesise. I remember this Roddy Woomble song, from his first album, the one that was sorrow, and was Scotland, through and through as a bowl of salted porridge, of sickly sugared Irn Bru. ‘Waverley Steps’, with its opening line, ‘If there’s no geography / in the things that we say’. Every word, I realise, is a situation. Alighting, departing; deferring or arriving. It’s 08:28 and I’m sitting at Waverley Station, having made my way down its steps, hugging my bag while a stranger beside me eats slices of apple from a plastic packet. I’ve just read Derek Jarman’s journal, the bit about regretting how easily we can now get any fruit we want at any time of year. He laments that soon enough we’ll be able to pick up bundles of daffodils in time for Christmas. The apples this girl eats smell of plastic, of fake perfume, not fruit. I’m about to board a train that will take me, eventually, to Thurso and then on via ferry to Orkney. I wonder if they will have apples on Orkney; it’s rumoured that they don’t have trees. Can we eat without regard to the seasons on islands also?

I needn’t have worried. Kirkwall has massive supermarkets. I check my own assumptions upon arrival, expecting inflated prices and corner shops. I anticipated the sort of wind that would buffet me sideways, but the air is fairly calm. I swill a half pint of Tennents on the ferry, watching the sun go down, golden-orange, the Old Man of Hoy looming close enough to get the fear from. Something about ancient structures of stone always gives me vertigo. Trying to reconcile all those temporal scales at once, finding yourself plunged. A panpsychic sense that the spirit of the past ekes itself eerily from pores of rock. Can be read in a primitive braille of marks and striations. We pick our way through Kirkwall to the SYHA hostel, along winding residential streets. I comment on how quiet it is, how deliciously dark. We don’t see stars but the dark is real, lovely and thick. Black treacle skies keep silent the island. I am so intent in the night I feel dragged from reality.

Waking on my first day, I write in my notebook: ‘the sky is a greyish egg-white background gleaming remnant dawn’. In the lounge of the hostel, someone has the telly on—news from Westminster. Later, I’m in a bookshop in Stromness, browsing books about the island while the Radio 2 Drivetime traffic reports of holdups on motorways circling London. Standing there, clasping Ebban an Flowan, I feel between two times. A slim poetry volume by Alec Finlay and Laura Watt, with photographs by Alastair Peebles, Ebban an Flowan is Orkney’s present and future: a primer on marine renewable energy. Poetry as cultural sculpting, as speculation and continuity: ‘there’s no need to worry / that any wave is wasted / when there’s all this motion’. New ideas of sustainability and energy churn on the page before me, while thousands down south are burning up oil on the London orbital.

When we take a bus tour of Mainland Orkney’s energy sources, we play a game of spotting every electric car we see. Someone on the bus, an academic who lives here, knows exactly how many electric cars there are on the island. There’s a solidarity in that, a pride in folk knowledge, the act of knowing. On the train up to Thurso, I started a game of infrastructure bingo, murmuring the word whenever I spotted a pylon, a station or a turbine. Say it, just say it: infrastructure. Something satisfying in its soft susurration, infra as potential to be both within and between, a shifting. Osmosis, almost. The kinesis of moving your lips for fra, feeling a brief schism between skin and teeth. A generative word. Say it enough times and you will summon something: an ambient awareness of those gatherings around you, sources of fuel, object, energy.

The supermarkets in Kirkwall seem like misplaced temples. This was me idealising the remoteness of islands, wanting to live by an insular, scarcer logic. The more we go north, the more scarcity we crave—a sort of existential whittling. Before visiting, I envisioned the temperature dropping by halves. On the first night, warm in my bed, I write: ‘To feel on the brink of something, then ever equi-distant’. The WiFi picks up messages from home. Scrolling the algorithmic rolls of Instagram, I feel extra-simultaneous with these random images, snapshots of happenings around the world. Being on an island intensifies my present. In Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun (2016), a memoir of recovery and return on Orkney, Liptrot writes of ‘waiting for the next gale to receive my text messages’. On the whims of billowing signal, we wait for news of the south to arrive. Maybe I was an island and I wanted my life elsewhere to vanish, disappear in a wall of wind; I wanted to exist just here, in a hullabaloo of nowness.

I say an island, but of course Orkney is more an archipelago. And I’m on the Mainland, home to the burghs of Stromness and Kirkwall. Here for the ASLE-UKI conference, there wasn’t time to visit the harbour at Scapa, or the neolithic village of Skara Brae or the stone circle Ring of Brodgar. I spend most of my time in the town hall opposite Kirkwall’s impressive, sandstone cathedral, aglow by night with fairy lights strung in surrounding trees. Yes, trees. Orkney has trees. They are often gnarled-looking and strange, stripped by wind or held up inside by steel plinths. Anthropocene arboreal hybrids. But still they are trees. Using my plant identification app, I find hazels and birches. Autumn is traceable in the swirls of thin leaves that skirt the pavement, tousling our sense of a general transition.

At one point in the trip, we visit the Burgar Hill Energy Project in Evie, alighting from the bus to stand underneath several massive turbines. The sound is wonderful, a deep churning whirr that feels like the air pressed charge on repeat. Under the chug chug chug of those great white wings we gathered, listened, moved and dispersed. I watch as our tight knit group begins to fragment; we need time apart to absorb this properly, little cells bouncing off and away from each other, quietly charged, loosening dots of pollen. Some of us finding the outer reach of the hill, looking for a view or panorama, leaning back to snap a photograph. I film the shadows windmilling dark the rough green grass. Capturing the turbines themselves seemed almost obscene. I don’t know why I was making them into idols, afraid to reduce them to pictures. It was easier to glimpse them in pieces, a flash of white, synecdoche. My friend Katy and I agreed the best photos were the ones out of focus, a bird-like blur against the blue.

Places I have been hit by wind:

I am an air sign, Gemini, and there is something about losing your breath to elemental forces. I think I once finished a poem with a phrase like, ‘lashing the planetary way of all this’. We used to stand in the playground at school, brandishing our jackets like polyester wings, letting the wind move us forward, staggering in our lightweight bodies, our childish intuition of the way of the world. The pleasure in surrendering. Making of your body a buffeted object. Returning to Glasgow, I soon find myself hit with a cold, preemptive fresher’s flu; a weight on my chest, a diaphragm lag. A sense of my body heaving against itself.

On Orkney, I can smell the salt from the sea. Earlier in the summer, I was struck with wisdom tooth pain, the kind that requires salt-water rinses every half hour, not to mention agonised gargles of whisky. Wasting my precious bottle of Talisker. Amid the haze of those painkiller days, I felt closer to an elemental heat. Metonymically, I was inhaling islands. The taste of self-preservation, of necessary self-sustenance, is never as strong and unwanted as when you want a part of yourself to be wrenched out of you. Pulling teeth is an easy metaphor for lost love, or other forms of psychic distress. Breaking apart, making of the self an archipelago. There’s that song by The National, ‘I Should Live in Salt’, which always sticks in my head in granular form, occasional line. Refrain of refrains, ‘I should live in salt for leaving you behind’. I never knew whether Matt Berninger was singing about preservation or pain, but I saw myself lying down in a kelp bed, child-size, letting the waves lap over my body, salt suffusing the pores of my skin. Begin again, softer.

The rain here is more a tangential shimmer. I wake up to it, dreaming that my window was broken and no-one would bother to fix it. Fear of boundaries loosened, the outside in. The future as a sheet of glass, a shelf you could place your self on and drink. Salt water rinse and heat of whisky. We leave the hostel early and wander beyond the Kirkwall harbour, to the hydrogen plant bordering an industrial estate. Katy and I discussed our fondness for industrial estates as homely reminders. She would go running, and wherever she ran the industrial zones were inevitable. As if in any city you would reach that realm, it called you in with its corrugated fronts and abrasive loneliness. My love for the canal, biking up through Maryhill where the warehouses watch serenely over you, loom behind trees, barely a machinic rumble disturbing the birds. We traced the edge of a man-made waterfront, a crescent curving lip of land. The way it curled was elliptical, it didn’t finish its inward whorls of land upon water, but still I thought of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, or the cinnamon buns I bought from the Kirkwall Tesco. Finding a bench, we ate bananas for breakfast, looking out at the grey-blue sea, our fingers purpling with the cold. I like to think of the banana, Katy said, as a solid unit of energy. Here we were, already recalibrating reality by the logic of pulse and burn and calories. Feeling infra.

I love the words ‘gigawatt’, ‘kilocal’, ‘megabyte’. I like the easeful parcelling up of numbers and storage and energy. I am unable to grasp these scales and sizes visually or temporally, but it helps to find them in words.

We learn about differences between national and local grids, how wind is surveyed, how wave power gets extracted from the littoral zone. My mind oscillates between a sonar attentiveness and deep exhaustion, the restfulness gleaned from island air and waking with sunrise. I slip in and out of sleep on the bus as it swerves round corners. I am pleasantly jostled with knowledge and time, the precious duration of being here. Here. Here, exactly. This intuition vanishes when I try to write it. A note: ‘I know what the gaps between trees must feel like’. Listening to experienced academics, scientists and creatives talk about planes, axes, loops and striations, ages of ages, I find myself in the auratic realm of save as…, dwelling in the constant recording of motion, depth and time. Taking pictures, scribbling words, drawing maps and lines and symbols. We talk of Orkney as a model for the world. Everything has its overlay, the way we parse our experience with apps and books and wireless signals. Someone takes a phone call, posts a tweet. I scroll through the conference hashtag with the hostel WiFi, tracing the day through these crumbs of perspective, memories silently losing their fizz in the night.

I grew up by the sea, in Maybole, Ayrshire (with its ‘blue moors’, as W. S. Graham puts it), but a lot of my thalassic time was spent virtually. I loved video games like The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, where the narrative happened between islands, where much of the gameplay involved conducting voyages across the sea. The interstitial thrill of a journey. There were whirlpools, tornados, monsters rising from the deep. On Maidens Harbour, I could hardly reach that volcanic plug of sparkling granite, the Ailsa Craig, or swim out to Arran; virtually, however, I could traverse whatever limits the game had designed. The freedom in that, of exploring a world already set and scaled. Movement produced within constraint. In real life, mostly our bodies and minds constrain. What excites me now is what I took for granted then: the salt spray stinging my lips, the wind in my hair, the glint of shells bleached clean by the sea; a beautiful cascade of cliches that make us.

‘To wake up and really see things…passages from a neverland.’ Back in Glasgow, fallen upon familiar nocturnal rhythms, I find myself craving the diurnal synchrony I achieved in Orkney. Sleepy afternoons so rich in milky light. The vibrational warmth of the ferry’s engine, activating that primitive desire for oil, the petrol smell at stations as my mother filled up the car for journeys to England. My life has often been defined by these journeys between north and south, born in Hertfordshire but finding an early home in Ayrshire. Swapping that heart for air, and all porosity of potential identity. Laura Watt talked of her work as an ethnographer, interviewing the people of Orkney to find out more about their experiences of energy, the way infrastructural change impacts their daily lives, their health, their business. Within that collaboration, she tells us, there’s also a sense of responsibility: stories carry a personal heft, something that begs immunity from diffusion. Some stories, she says, you can’t tell again. The ethics of care there. I wonder if this goes the same for stone, the stories impregnated within the neolithic rocks we glimpse on Orkney. Narrative formations lost to history’s indifferent abstraction, badly parsed by present-day humans along striated lines, evidence of fissure and collision. All that plastic the ocean spits back, co-evolutions of geology and humans. Plastiglomerates along the shore. But Orkney feels pure and relatively litter-free, so goes my illusions, my sense of island exceptionalism. I become more aware of the waste elsewhere. The only person I see smoking, in my whole time there, is a man who speeds his car up Kirkwall’s high street. Smoke and oil, the infinite partners; extraction and exhaustion, the smouldering of all our physical addictions. Nicotine gives the body a rhythm, a spike and recede and a need.

We learn of a Microsoft server sunk under the sea, adjacent to Orkney. There’s enough room in those computers, according to a BBC report, to store ‘five million movies’. And so the cloud contains these myriad worlds, whirring warm within the deep. Minerals, wires and plastics crystallise the code of all our text and images. Apparently the cooler environment will reduce corrosion. I remember the shipyard on Cumbrae, another island; its charnel ground of rusted boats and iron shavings. The lurid brilliance of all that orange, temporal evidence of the sea’s harsh moods, the constant prickle of salt in the air. The way it seems like fire against all those cool flakes of cerulean paint. I wrote a blog post about that shipyard once, so eager to mythologise: ‘Billowing storms, sails failing amidst inevitable shipwreck. It’s difficult to imagine such disasters on this pretty island, yet there is an uncanny sense to this space, as if we have entered a secret porthole, discovered what was supposed to be invisible to outsiders…The quietness recalls an abandoned film set’. Does tourism lend an eerie voyeurism to the beauty we see, conscious of these objects, landscapes and events being photographed many times over? Perhaps the mirage of other islands and hills glimpsed over the blue or green is more the aura of our human conceptions, archival obsession—the camera lights left buzzing in the air, traced for eternity.

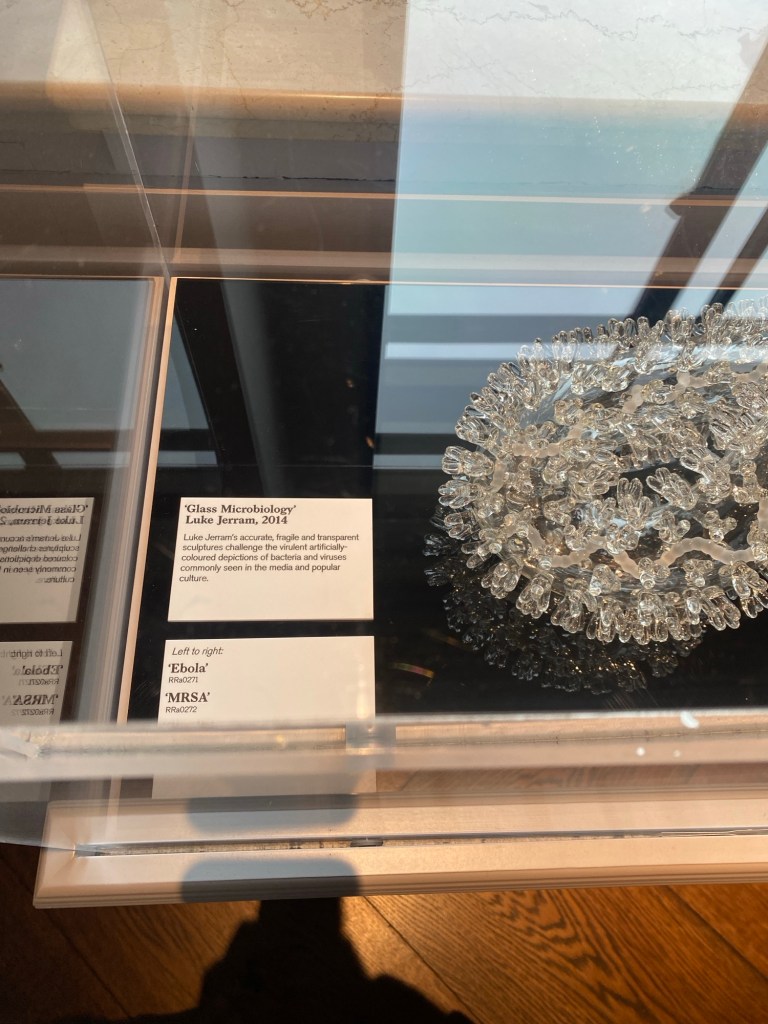

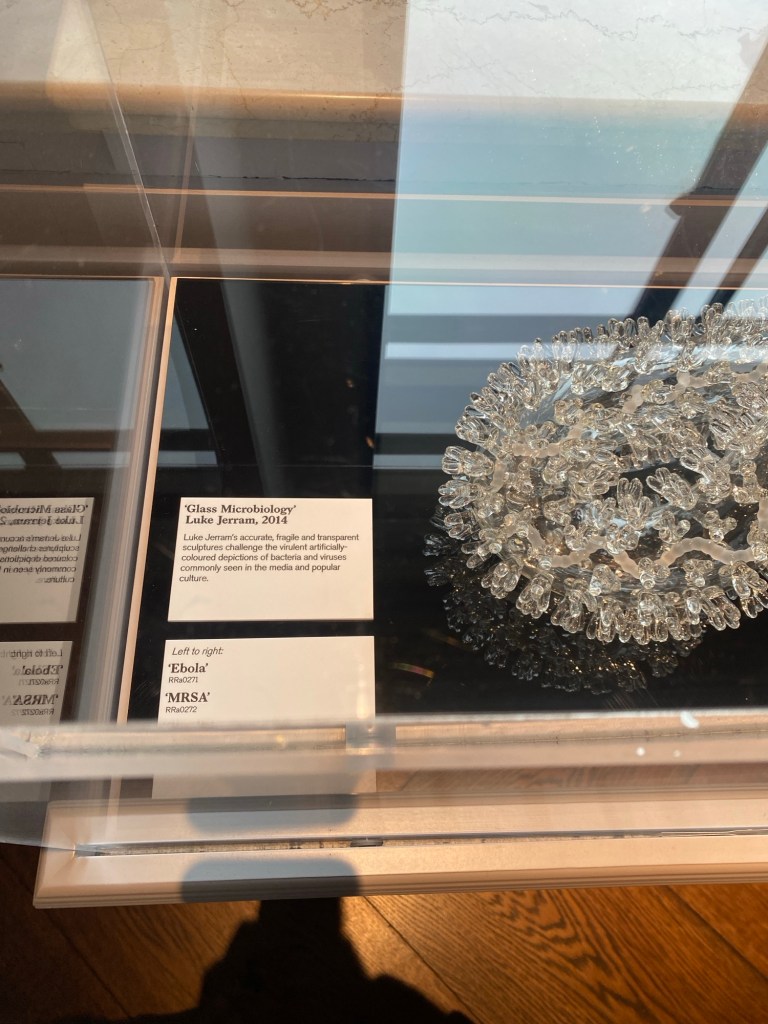

I come to Orkney during a time of transition, treading water before a great turn in my life. Time at sea as existential suspension. There have been some departures, severings, personal hurts, burgeoning projects and new beginnings. A great tiredness and fog over everything. ‘Cells of fuel are fuelling cells’. At the conference, my brain teems with this rich, mechanical vocabulary: copper wires and plates and words for wattage, transmission, the reveries of innovation. There is a turning over, leaf after leaf; I fill up my book with radials, coal and rain. My mind attains a different altitude. I think mostly about the impressions that are happening around me: the constant flow of conversation, brought in again as we move between halls and rooms, bars and timelines in our little human estuaries. We visit Stromness Academy, to see Luke Jerram’s ‘Museum of the Moon’: a seven-metre rendition of lunar sublimity, something to stand beneath, touch, lie under. I learn the word for the moon’s basaltic seas is ‘Maria’, feel eerily sparked, spread identity into ether. We listen, quietly, in the ambient dark, taking in composer Dan Jones’ textures of sound, the Moonlight Sonata, the cresting noise of radio reports—landings from a future-past, a lost utopia.

On Friday night, Katy and I catch the overnight ferry back to Aberdeen. Sleep on my cinema seat has a special intensity, a falling through dreams so vivid they smudge themselves on every minute caught between reading and waking. Jarman’s gardens enrich my fantasy impressions, and I slip inside the micro print, the inky paragraphs. I dream of oil and violets and sharp desire, a pearlescent ghost ship glimmer on a raging, Romantic sea. Tides unrealised, tides I can’t parse with my eyes alone; felt more as a rhythm within me. Later, on land I will miss that oceanic shudder, the sense of being wavy. I have found myself like this before, chemically enhanced or drunk, starving and stumbling towards bathrooms. We share drinking tales which remind me of drowning, finding in the midst of the city a seaborne viscosity of matter and memory, of being swept elsewhere. Why is it I always reach for marinal metaphor? Flood doors slam hard the worlds behind me. There are points in the night I wake up and check my phone for the time, noticing the lack of GPRS, or otherwise signal. I feel totally unmoored in those moments, deliciously given to the motioning whims of the ferry. Here I am, a passenger without place. We could be anywhere, on anyone’s ocean. I realise my privilege at being able to extract pleasure from this geographic anonymity, with a home to return to, a mainland I know as my own. The ocean is hardly this windswept playground for everyone; many lose their lives to its terminal desert. Sorrow for people lost to water. Denise Riley’s call to ‘look unrelentingly’. I sip from my bottle, water gleaned from a tap in Orkney. I am never sure whether to say on or in. How to differentiate between immersion and inhabitation, what to make of the whirlwinds of temporary dwelling. How to transcend the selfish and surface bonds of a tourist.

The little islands of our minds reach out across waves, draw closer. I dream of messages sent from people I love, borne along subaquatic signals, a Drexciya techno pulsing in my chest, down through my headphones. My CNS becomes a set of currents, blips and tidal replies. A week later, deliriously tired, I nearly faint at a Wooden Shijps gig, watching the psychedelic visuals resolve into luminous, oceanic fractals. It’s like I’m being born again and every sensation hurts, those solos carried off into endless nowhere.

Time passes and signal returns. We wake at six and head out on deck to watch the sunrise, laughing at the circling gulls and the funny way they tuck in their legs when they fly. These seabirds have a sort of grace, unlike the squawking, chip-loving gulls of our hometowns, stalking the streets at takeaway hour. The light is peachy, a frail soft acid, impressionist pools reflecting electric lamps. I think of the last lecture of the conference, Rachel Dowse’s meditations on starlings as trash animals, possessing a biological criticality as creatures in transition. I make of the sky a potential plain of ornithomancy, looking for significant murmurations, evidence of darkness to come. But there is nothing but gulls, a whey-coloured streak of connected cumulus. The wake rolls out behind us, a luxurious carpet of rippling blue. We are going south again. The gulls recede. Aberdeen harbour is a cornucopia of infrastructure, coloured crates against the grey, with gothic architecture looming through morning mist behind.

Later I alight at the Waverley Steps again. Roddy in my ear, ‘Let the light be mined away’. My time on the island has been one of excavation and skimming, doing the work of an academic, a tourist, a maker at once. Dredging up materials of my own unconscious, or dragging them back again, making of them something new. Cold, shiny knowledge. The lay of the heath and bend of bay. I did not get into the sea to swim, I didn’t feel the cold North rattle right through my bones. But my nails turned blue in the freezing wind, my cheeks felt the mist of ocean rain. I looked at maps and counted the boats. I thought about what it must be like to cut out a life for yourself on these islands.

Home now, I find myself watching badly-dubbed documentaries about Orkney on YouTube, less for the picturesque imagery than the sensation of someone saying those names: Papay, Scapa, Eday, Hoy. Strong names cut from rock, so comforting to say. I read over the poems of Scotland’s contemporary island poets, Jen Hadfield for Shetland, Niall Campbell for Uist. Look for the textures of the weather in each one, the way they catch a certain kind of light; I read with a sort of aggression for the code, the manifest ‘truth’ of experience— it’s like cracking open a geode. I don’t normally read like this, leaving my modernist cynicism behind. I long for outposts among rough wind and mind, Campbell’s ‘The House by the Sea, Eriskay’: ‘This is where the drowned climb to land’. I read about J. H. Prynne’s huts, learn the word ‘sheiling’. Remember the bothies we explored on long walks as children. There’s a need for enchantment when city life churns a turbulent drone, so I curl into these poems, looking for clues: ‘In a fairy-tale, / a boy squeezed a pebble / until it ran milk’ (Hadfield, ‘The Porcelain Cliff’). Poetry becomes a way of building a shelter. I’m struck with the sense of these poets making: time and matter are kneaded with weight and precision, handled by pauses, the shape-making slump of syntax. Energy and erosion, elemental communion. Motion and rest. My fragile body becomes a fleshwork of blood and bone and artery, hardly an island, inclined to allergy and outline, a certain porosity; an island only in vain tributary. I write it in stanzas, excoriate my thoughts, reach for someone in the night. I think about how we provide islands for others, ports in a storm. Let others into our lives for temporary warmth, then cast ourselves out to sea, sometimes sinking.

Why live on an island? In Orkney we were asked to think with the sea, not against it. To see it not as a barrier but an agential force, teeming with potential energy. Our worries about lifestyle and problematic infrastructure, transport and connection were playfully derided by a local scholar as ‘tarmac thinking’. Back in a city, I’ve carried this with me. The first time I read The Outrun was in the depths of winter, 2016, hiding in some empty, elevated garrett of the university library. I’d made my own form of remoteness; that winter, more than a stairwell blocked me off from the rest of existence. Now, I read in quick passages, lively bursts; I cycle along the Clyde at night and wonder the ways in which this connects us, its cola-dark waters swirling northwards, dragged by eventual tides. I circle back to a concept introduced by anthropologists at Rice University, Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer, ‘sister cities of the Anthropocene’: the idea that our cities are linked, globally, by direct or vicarious physical flows of waste, energy and ecological disaster. This hydrological globalisation envisions the cities of the world as a sort of archipelago, no metropolis safe from the feedback loops of environmental causality, our agency as both individuals and collectives. On Orkney, we were taught to think community as process, rather than something given. I guess sometimes you have to descend from your intellectual tower to find it: see yourself in symbiosis; your body, as a tumbled, possible object: ‘All arriving seas drift me, at each heartbreak, home’ (Graham, ‘Three Poems of Drowning’).