Separation is something that passes through your body. It happens on scales that feel biological, because at once so intimate and distant, clear and mysterious. The vertigo sensation when you see a diagram of the heart, or someone’s face fading in the moving window of a train. When I learn the words for things I can’t articulate. When someone says Brexit or mentions faraway disasters, or power lines being laid deep under the sea. Scientific processes that I can’t reach. Separation, transmission, event repeating. A curiosity towards ominous energies. I’m not just talking about the endless, five o’clock stories, beamed through radio waves. Brexit is as Brexit does. Most analogue hour. How many of us woke up that Friday morning, after the fact, with stomach aches? The undigest of all our country, rent broad and familiar on all the news.

~

As history seems to be compressing, rapidly, in a chaotic present which seeks to smooth with legislative violence the rich diversity of our past, stories of migration and change become vital.

With vague direction, I walk over the motorway bridge twice to get back to Glasgow city centre. The trees in Kinning Park are singed with vermillion; it’s early October. I ascend the footbridge, just slightly hungover. The sight of the traffic fills me motion again, after a night of luxurious slosh and dark of stasis. Screen light and honeydew shoegaze. Cars are barely there, but they go places. They leave a carbon trail behind. Watching from the sun-drenched bridge, I carry my stories and see them swept up in lines I can’t manage. Later, I try to write. I am looking for a flow, a sense of circuitry. The sentences whir.

Then I step into the exhibition. There is the clarity of photography, more like a series of windows. Windows I see inside windows. The glass steams up in certain types of feeling, translated as light.

~

The themes of the recent Lightwaves exhibition at Street Level Photoworks, featuring the work of Mat Hay, Josée Pedneault, Bertrand Carrière, and Melanie Letoré, are moving histories: those of heritage, migration and the storytelling inherent within. I have a special familiarity with Letoré’s work and practice, having served as her hospitality comrade back in 2016 and since then having worked with her on a personal project: a weekly Google doc record of our lives and thoughts, sprawled in text, image (art & photographs), questions, lists, poetry, fiction and essays. The name of our project remains tendentiously secret, a bright hard candy. Keeping a ledger with someone who I tend only to encounter IRL on chance occasion (gliding bikewise down the motorway, drinking OJ in basement bars) feels a bit like an odyssey. An orbit of thought. Each week we find out more about each other’s pasts, our present fears and desires, our personalities. It’s a bit like trading journals at weekly sleepovers, except there’s the sense that each post on our shared document is less a private thought and more like something that needed airing, that needed figuring out in the shared forms of writing and visual expression. Writing as performative output, the act alone a delectation. I love the sense of sisterhood that comes with this kind of sharing, like when I was wee and my cousin and I would read each other’s palms and tarot, tell our futures.

I proposed the project to Melanie after many months of following her blog, Rectangledays, whose premise is the daily post of a fresh photograph. The blog goes back several years and serves as a sort of photo diary, a luminous archive of many little windows into moments in time. Some I recognise from the days we worked together at the restaurant: pictures of a decimated wedding cake, a lonesome chair in a stairwell, a bunch of crutches propped against the fence, another colleague’s bloodied toe, wadded with cotton. I love these photos as a testament to the physicality of hospitality, the importance of objects and tools (knives often feature) to our work, the endurance required: poor Shelby with the bloodied toe, acquired on a wild night out, would’ve hobbled along serving tables with her injury, no complaints, shift after shift.

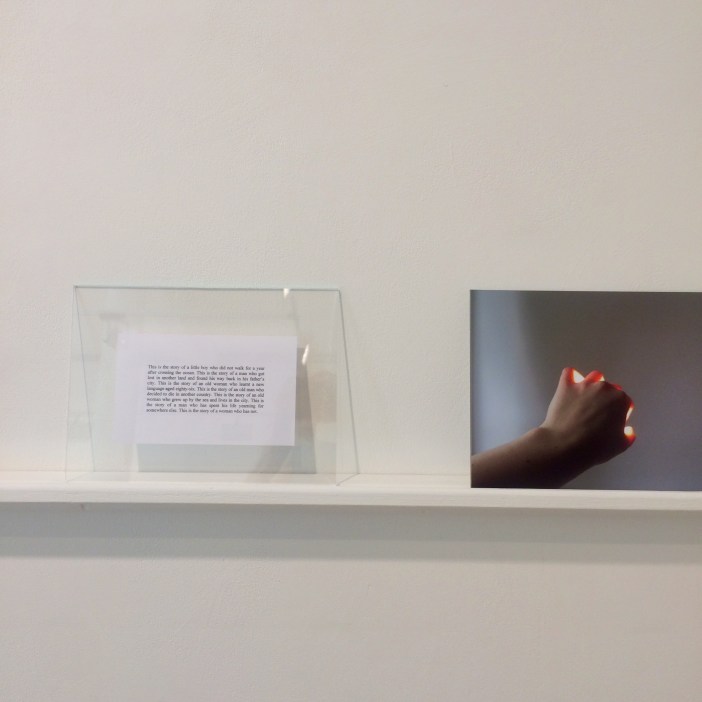

It’s a total treat to see Melanie’s work in an exhibition context. Stories that maybe she’s written about in our ledger come to life in the distillation of pictures in a bright clean room. Privacy rents a very public space. The other photographers in the exhibition have their work blown up, pressed across the white, whereas Melanie’s are much smaller, identical in size, sitting parallel on a wall. The pictures are thick, giving the impression of little books, the three-dimensional aspect implying that the story is more complicated than the image allows. The image contains itself, and then the negative space of all these stories, quietly sporing. Much of her work is about shining a light on the intricacies of identity: Melanie’s grandparents migrated from North America to Europe in the 1950s, and she herself has moved from childhood Switzerland and found a home in Glasgow, as an adult. Her work feels like a dialogue with the everyday world around her, and maybe the people back home, the family who live their own lives many miles away. Photography as postcards without text on the back. Or maybe photography captioned with invisible ink, ink that only some people can see; others parsing their own specificity from the image. That’s the beauty of Melanie’s work: it’s tender and personal, but there’s a humanist impulse in there somewhere too, rent with a complexity that asks us to think about where people come from, how they live, where they touch the lives of others. Feelings, adventures, intimacies, routines, leisure and food.

A certain nourishment. I feel privileged to have access to some of the thoughts behind these images. Reading Melanie’s writing, I find myself adrift on all these planes of migration. The title of her exhibition, No You Without, comes from Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost. When told of the Wintu in north-central California, who use the cardinal directions rather than the words left and right to capture their bodies, Solnit writes, ‘I was enraptured by this description of a language and behind it a cultural imagination in which the self only exists in reference to the rest of the world, no you without mountains, without sun, without sky’. With this perspective, we realise our own contingency in the context of a relatively stable world. Recently, I’ve been wondering about where the ‘you’ is situated in my own poetry, who exactly it is I’m addressing. Who is the ‘you’ in a photograph, what kinds of hailing occur when we look at a portrait, or perhaps a landscape. Where are we situated and within whose vision. There’s a piece in No You Without where a woman, I think in fact Melanie herself, has awkwardly levitated her body by propping it between two counters or surfaces. I’m struck with the fact of the body suspended so precisely this way, making a new morphology of her being. Like when you are a child and find ingenious ways to get across a room without touching the lava-strewn floor, or like lying upside down for too long and seeing how precarious your sense of space is. When you are forced to appreciate gravity, pressure, connections. The objects that make us by dint of negation.

In Melanie’s images, I seek fresh orientations. These are subjects which reflect process rather than point; they are a document in the quest for self in a sea of myriad reflections, a very real sea which threatens with its sweep. I see red ribs of meat, black curls through black curtains, a strand of hair overlooking an island, the pinching of elbow flesh, a rainbow, the gnarled remainders of landscape’s heap, two boys rolling around on the beach. Each image demands its own sense of scene, of identity in place. I have a sense of capturing, that one slight second that splits and releases: the clouds come in, the flesh smooths back, the rainbow ceases to be.

While the images do not document explicit ‘narrative’ as such, it’s clear there’s an intimacy threading between them. I wonder if we are encouraged to pick up the images and study them, the way you might lift family photos off the mantelpiece, stealing a look at the back for captions. In the exhibition notes, it’s suggested that the migration of Melanie’s grandparents to Europe, and all their associated trauma, comprises ‘another layer to her search for identity’. What we lose or leave behind. What we carry with us. A memory of blue, of sky, of something that represents the not-knowing, but nevertheless the feeling. That which comes, regardless of narrative or language. I planted a thought. Photography bears the visual seeds.

I’m reminded of a passage in Sophie Collins’ book small white monkeys, one that Melanie and I have discussed often:

Patterns of shame can of course be inherited, be broken, halted, but mostly they are carried on through, like mottos, or emotional heraldry.

Maybe we carry something of what our parents and grandparents taught us, or experienced. The learned behaviours, observational ticks of outburst or repression. Frequencies and cycles of confession or pain, the arguments which pixelate our childhood memories with varying degrees of trauma. A traumatic tartan, stitched to the furniture of our daily lives; a ravelled print of practices and patterns of thought and feeling.

We find ourselves reenacting the affects of others, those we are close to. Mostly, we don’t mean to. There are just these things we remember, ticking away in our brain and blood.

Such memory persists like a stick of brighton rock with the motto carried through, except you can break off the stick at any point, you can shatter the neat black letters. The rock of the shards tastes sweet and mint, is cleansing.

But it sticks to your teeth. Shame sticks also.

You can cut yourself on your own quick memory.

When I learn the words for things I can’t articulate. Surely ‘emotional heraldry’ captures this miasma of maybe incalculable feelings I might attribute to family experience? A coat of arms to bear, whose pattern is fading before me, or intensifying within me. Heraldry, inheritance. Jewishness on my mother’s side, ethnicity unrecognised, religious cycles and traumatic pasts; a kind of implicit migrancy that is only tangible in visiting. Stories my nan tells about ancestors whose names are like keys to dust-filled chests, mildewed letters, somewhere deep and distant. But then livable: a trip to Amsterdam, family graves and suddenly the pulses of history might glow in my veins. That heat is a shame. Peeling yourself from the easy determinism of ‘family’ and then finding family wherever you read. Recently I was struck hard by this essay by Daisy Lafarge on maternal approaches to poetics, or looking to whatever texts provide a sort of mothering supplement, rich with emotional truths. The wrestle with essentialism, with forms of belonging. I am someone’s daughter when I read a poem or look at a photograph. Sometimes I am otherwise lost. I am that altogether vulnerable.

I guess I’m an immigrant too of sorts. Moving from England to Scotland at a very young age, being acutely aware of my Englishness and thus playground shame because of the markers of accent, and yet proud at the difference, to be different. Melanie’s photos teach me to sympathise with other kinds of present, and presence. They are fleeting and insouciant, playful in one sense, but otherwise make me want to stockpile and archive with a kind of serious fever. I want to know everything about the people in these images, scour their diaries and ask them their names. But I also want to leave them alone, up on the shelf where their lives can be quiet and still, and yet somehow heard, in the seeing. Maybe an image is a kind of speech; it allows us to separate, and to parse our connections. To halt in the flow of feeling, to carry a place or a person; to illumine.

~

Lightwaves is on until 25th November at Street Level Photoworks, Glasgow.