I was turning all the lights off, trying to mute history. There were several moments in which it felt like things were changing, possibly blossoming for the better. The aftermath stung and went backwards again. There was a song about the M62 I followed briefly, thinking about motorways more generally and something expansive and grey, crossing the Pennines eventually. For a week, I wrote down descriptions of the sky. Mostly they read: the sky today is grey. I then started noting the patterns in Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals, which often begin with vignettes of the morning:

3rd February. A fine morning, the windows open at breakfast.

6th March. A pleasant morning, the sea white and bright.

26th May. A very fine morning.

31st May. A sweet mild rainy morning.

2nd June. A cold dry windy morning.

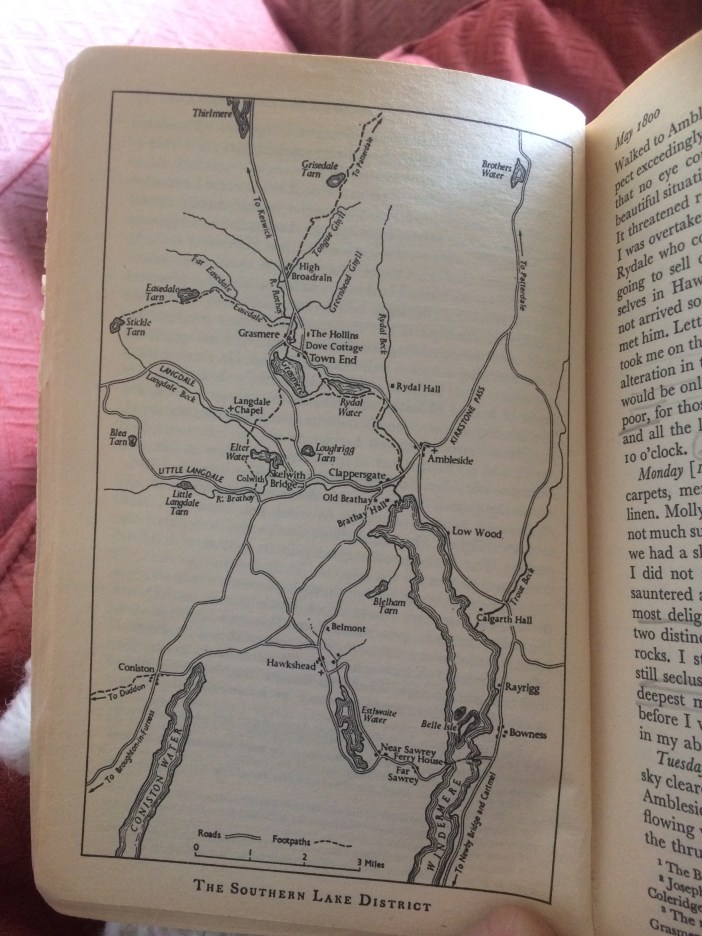

Mostly, she summarises the day. There is much letter-writing, Coleridge dining, William writing. Walking, cooking, taking guests. There is a rhythm and comfort to her entries, the circling of Ambleside, the sauntering in sun and air. Days condensed and hours expanded, cute little details in pastoral glimpses: ‘Pleasant to see the labourer on Sunday jump with the friskiness of a cow upon a sunny day’. She sees into the life of things. She inspires me to mark the simple, joyous moments of daily existence. Like walking home along Sauchiehall Street (the nice part towards Finnieston), close of midnight, seeing a couple in each other’s arms, sobbing, the man with a bunch of flowers held behind his back. They were not by any means striking flowers, probably bought cheap and last minute. I wonder what sort of gesture they were supposed to convey. At what point in the night did he decide to buy them; did he attain them from those wandering women who pray upon drunks with their floral wares? Did he cut himself, ever so slightly as he paid for those unlovely thorns? Is love always a form of apology for self? The self when it expands beyond too much of itself, hotly craving?

17th March. I do not remember this day.

It seems irrelevant to say, today is Easter Sunday. Jackdaws torment me in the expensive fruit of a wakeful morning. I imagine pomegranate seeds falling from a pale blue sky. These days unfold with wincing clarity, like the hypnotic drag of a Sharon Olds poem: ‘I could see you today as a small, impromptu / god of the partial’. There are things we are maybe not supposed to remember. As if survival were a constant act of lossy compression. Like a contract between two people, pinkie promise, except one of you has broken it. Has let out the glitches. Your dreams and daily reveries are full of the content you’re not meant to remember. You are clasping this thing as if it might live again, and indeed it might really. It is not easy to simply file away memory. Its particular phraseology of physical pain comes floating to the surface regardless. There are techniques of displacement. Letting yourself shimmer in the wind. It was one more step to be gone again. So every song I went to put on, clicking the laptop, he was like, stop, it’s too sad. When they ask what’s wrong and you’re smiling instead, worrying the edge of your lips into muscles you don’t recognise at all. The room was a singular bottle of beer and a breeziness to other people’s sweetness. They wear lots of glitter and laugh as we did once. They are singing. I feel like the oldest in a test of forever. But anyway this is all only temporary. Things break down but they do not go away.

30th March. Walked I know not where.

I watch a film about plastic in the ocean. They haul fish after fish, bird after bird, prise exorbitant quantities of bottle caps, ring pulls, microbeads and indiscernible fragments from stomachs and lungs. It is quite the display. Hopelessly choking. Seems obscene to describe that deep blue as ever pure again. There are patches of plastic in all its particles swirling. It makes not an island exactly, more like a moment in species collision. Whales absorb plastic in the blubber of their skins, digesting slowly the poisons that kill them. I wrote a story about a whale fall once. The protagonist trains in swimming, in underwater breathing, in order to enter other worlds: ‘This place is a deep black cacophony; you hear the noises, some noises, not all the noises, and you feel the pressure ripple pulling under you’. There have been bouts of sleeplessness this month that feel like dwelling inside a depleting carcass. If every thought dragged with subaquatic tempo. Blacking out at one’s desk into sleep. Forgetting in the glare of screen flickers. I meet people for coffee and feel briefly chirpy, stirring. There are pieces of colour, uncertain information, clinging to the shuddering form of my body. Do not brush my hands, for fear of the cold. I am so blue and when he squeezes my fingers my insides feel purple. The woman at the counter remarked on the cold of my hands. I am falling for the bluest shade of violet. How anyway in such situations I become the silent type as I never do elsewhere. So ever to cherish a bruise as violet or blue. I polish vast quantities of glassware, lingering over the rub and sheen. One song or another as 4.30am aesthetic.

Emily Berry: ‘All that year I visited a man in a room / I polished my feelings’.

The questions we ask ourselves at work form a sort of psychoanalysis, punctuated by kitchen bells and the demands of customers. What superpower would you have? The ability to live without fear of money. We laugh at ourselves as pathetic millennials. I have nothing to prove but my denial of snow, power-walking up Princes Street on the first bright day of the year. The sky is blue and the cold flushes red in my cheeks. But I am not a siren, by any means; I wish mostly for invisibility. The anthem for coming home the long way is ‘Coming in From The Cold’ by the Delgados, feeling the empathy in lost dreams and the slow descent into drunkenness that arrives as a beautiful warning. Like how he deliberately smashed his drink on the floor in the basement out of sheer frustration with everything. The ice was everywhere. As though saying it’s complicated was an explanation for that very same everything. The difficulty of cash machines. Emily Berry again: ‘I wanted to love the world’. In past tense we can lend shape to our feelings. Will I know in a week or more the perfect metaphor for this dread, this echo chamber of grey that longs to be called again? I punch in four numbers.

I covet my exhaustion in slow refrain. There are people whose presence is an instant comfort. There are people you’d like to kiss in the rain; there are people you’d kiss in the rain but never again. What of the gesture of that bouquet? Surprise or apology? The sky is catching the mood of our feelings. Is this a melancholic tone of regret, or maybe an assured and powerful one? I twist round the memory of a mood ring; its colours don’t fit. I photograph the rings beneath my eyes, finishing an eleven hour shift. She shoves rose-petal tea biscuits under my nose but I smell nothing. I watch the chefs at work, caressing their bundles of pastry and sorrow/sorrel and rocket. I climb many stairs and assemble the necessary detritus of another funeral. Sadness requires a great deal of caffeine.

I eat mushrooms on toast with Eileen Myles. I long for the lichens on the trees of Loch Lomond. I sleep for three hours in Glasgow airport, on and off, cricking my neck and drifting in and out of vicarious heartbreak. Lydia Davis is often perfect:

But now I hated this landscape. I needed to see thing that were ugly and sad. Anything beautiful seemed to be a thing I could not belong to. I wanted to the edges of everything to darken, turn brown, I wanted spots to appear on every surface, or a sort of thin film, so that it would be harder to see, the colours not as bright or distinct. […] I hated every place I had been with him.

(The End of the Story)

Must we coat the world in our feelings? What of the viscosity that catches and spreads on everything? There is an obscenity to beauty in the midst of defeat. Year after year, I find myself dragged into summertime sadness. There is so much hope in the months of June and May, soon to dwindle as July runs spent on its sticky rain. The lushness of a city in bloom, all fern and lime, is an excess beyond what dwells inside, the charred-out landscapes of endless numbness—or ever better, missing someone. We covet the world’s disease as externalisation of our hidden pain. Let things fragment and fall away; let there be a sign of change in motion. How hard it is to be happy around depleted friends; how hard it is to be sad among joyous friends. They pop ecstasy and go home for no reason. It is self-administered serotonin that mostly buoys up the souls of the lonely. There were songs from the mid-noughties that now sound like somebody shouting down a coal mine. I want to offer them a smile and a cup of coffee. It’s all I have, the wholesome concatenation of smooth flat-whites.

There is a song by Bright Eyes, ‘If Winter Ends’: ‘But I fell for the promise of a life with a purpose / But I know that that’s impossible now / And so I drink to stay warm / And to kill selected memories’. Winter’s demise in conditional form. Alcohol convinces us of a temporary rush into the future that blooms and is good, is better than before. The drinkers I know have muffled recollections, blotted out mostly by false nostalgia. We covet a swirling version of life in the present, its generous screen flickers, its spirals of affect. We pair off in the wrong. There are days when nothing will warm me up—not the dust-covered space heater, not the hot water bottle, not the star jumps that scratch heart-rates out of the hour. Was it the same sensation, hanging on for his vowels on a hazy afternoon, four o’clock stolen from whatever it was I was supposed to be doing?

Summer, however, is forever. It is supposed to be best. The clocks skip forward.

I learn to riso-print. To work with the uncertain blot and stealth of brighter inks. What results is a marvel in teal and burgundy, splashed with cyan. See it as past with glitters of future.

In a cramped, fourth floor hotel room in Amsterdam, I lay on my bed, leg-aching, listening to ‘Shades of Blue’. Yo La Tengo get it, the vaporous sprawl of the days upon days, days replacing days: ‘Painting my room to reflect my mood’. It is a kind of overlay, the new versions of blue which are deeper maybe than they ever were before. Which lend alter-visions to original blues, the ones you thought were bad before. I see my first IRL Yves Klein in the Stedalijk museum. Words elude this particular blue. It is deep and extravagant and more oceanic than the ocean would dream of. I have no idea what materials or dreams created this blue. Lazuli, sapphires, the pigmented stain of a rare amphibian? It is the steady, infinite eye of the Pacific. It is sorrow itself, the wound of the world. The Earth bleeds blue, not red. It is this kind of blue, a supranatural blue. After the first crisp cold of a new blue day, the rest of the week is brumous and mild. My feet get wet in a cemetery. I learn that Paradise Valley is an affluent town in Arizona, and not in fact merely a Grouper album. I drink mint tea all week to detox, then stay up all night when I get home. The gin sodas sparkle within me for days, but I’m feeling guilty.

The canals are parallel, the streets are winding. There are neon and fishnetted girls in windows, drolly sipping mysterious drinks. Their eyes are heavily lined. Nobody is looking. The air is warm and spicy at night. The tourists admire displays of various erotic paraphernalia; I take pictures of the lights splashed gold on the water. They say if you get to know the place, you can really settle into a meandering layout. A guy at work supplants my name for ‘Marijuana’. I wonder if ever I’ll be someone’s Mary Jane, and what that means in the long run. Feels like a Green Day song. Marijuana, they’ll say, Marijuana I miss you. There are pockets of Finnieston that waft forever between early summer and fullness of June; evenings hung by the scent of a stoned hour poised on forever. I stay sober. I think of the river, the people and dreams it steals. The world crystallises with ridges of cold, so I must sleep beneath sheets in my click&collect coat. Blue-fingered, shivering.

Carl Sagan’s ‘Pale Blue Dot’ has been lingering on my mind: ‘Consider that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us’. I keep writing out line after line, just for the sake of avoiding full stops. I’m not yet ready for that singular compression, even as it strikes in its simple beauty.

There was the massive, narcotic blue of the sky from the airplane. A blue you can cling to. A blue you descend through.

Lana Del Rey: ‘Blue is the colour of the planet from the view above’.

Pop singers these days are attuned to new scales. That Bright Eyes song opens with a whole lot of static and children shouting, rasping. It is like watching some black-and-white film in a museum, shudders of war or monsters in every low boom and flicker. There are ways we strum ourselves out of the mourning. It’s okay to be enraged and frustrated. Oh Conor, how I love you: ‘and I scream for the sunlight or car to take me anywhere’. So when things fall apart, fray at the edges, I’m thinking of myself as a place, a location elsewhere, ‘just take me there’, and the ridge of my spine is a highway that ends where the best palm glows afire by its imaginary desert. The curve of my neck and uncertain horizon, something of all this skimming around by the brink of etcetera. What else do I have to say but, ‘it’s gonna be alright’, not even realising when I am quoting something. It is hot here, adrift on this sofa, then cold again.

The walks grow ever more indulgent, Mark Kozalek humming in my ear. I think of all his familiars. I think of my younger self thinking of all his familiars. Is it cats or is it women. How many supplements do we make of lust?

The day afterwards, it’s best to drink again. Grapefruit is cleansing. You can order whole pitchers but I choose not to. A certain suffusion of gossip and horror, ice cubes crunched between teeth to ease up the gaps where I’m meant to speak. I see Hookworms play the Art School and they were incredible: they were a rush they were eons of dizzy vigour and sweetness, the music you want to surrender to. I stop giving customers straws with their orders. It snowed again. I wasn’t drinking; I was wearing green for Paddy’s Day. I was so tired my eyes felt bruised. I keep dreaming of islands, motorbikes, exes; broken tills and discos. The flavour of these dreams in surf noir; like even in the city it’s as if a tidal pull is directing everything. I don’t mind being sucked away into nothing; I don’t mind feeling the impulse of a pale blue dot. At least in my sleep. A good collapse. The order of pain is reducing.

29th June. It is an uncertain day, sunshine showers and wind.

This week I will find a hill for my vision. New forms of erasure. I see myself boarding a train.

~

Yo La Tengo – Shades of Blue

Bright Eyes – If Winter Ends

Iceage – Pain Killer

Tessela – Sorbet

Bjork, Arca, Lanark Artefax – Arisen My Senses (Lanark Artefax remix)

CZARFACE, MF DOOM – Nautical Depth

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard – Barefoot Desert

Grouper – I’m Clean Now

Sean Nicholas Savage – So It Appears

Snail Mail – Pristine

Little Comets – M62

Manchester Orchestra, Julien Baker – Bad Things to Such Good People

Hop Along – How Simple

Frankie Cosmos – Apathy

Sharon Van Etten – I Wish I Knew

Amen Dunes – Believe

Cornelius, Beach Fossils – The Spell of a Vanishing Loveliness

Sun Kil Moon – God Bless Ohio

Good Morning – Warned You

Lucy Dacus – Addictions

The Delgados – Coming in From the Cold

Belle & Sebastian – We Were Beautiful

Mark Kozalek – Leo and Luna

Pavement – Range Life

Firestations – Blue Marble

The World is a Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid to Die – Heartbeat in the Brain

Manic Street Preachers – Dylan & Caitlin

Bob Dylan – Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues

Crosby, Stills & Nash – Hopelessly Hoping

Courtney Marie Andrews – Long Road Back to You

Grateful Dead – Box of Rain