Disclaimer: my middle name is Rose. This means nothing, as far as I’m aware. I have never received roses for Valentines (as far as I’m aware). What follows comprises an essay on what a rose is a song is a word is a rose(?), feat. the likes of Gertrude Stein, Idlewild, Oscar Wilde, Joyce, Yeats, the French Symbolists and Lana Del Rey…

🌹🌹🌹

Despite having two degrees in literary studies, a lot of my more convincing intellectual references were first encountered through music, not books. The Manic Street Preachers’ Holy Bible album introduced me to Foucault, Plath, Ballard, Nietzsche, Mailer and Pinter in one fell, aggressive swoop of a Richey Edwards lyric barked over the guttural shudder of Nicky Wire’s bass-lines. Gertrude Stein, the awkward goddess of modernism, first came to me via an Idlewild song—deep in some distant vestige of the noughties, when I still bought CDs. She’s mentioned in ‘Roseability’, the last single to be taken from the band’s 2000 breakthrough, 100 Broken Windows. It’s a typically angsty track, reflecting on the futility of being dissatisfied with the present and finding pathetic solace in the past: “stop looking through scrapbooks and photograph albums / because I know they won’t teach you what you don’t already know”. Say it and already you know, right? ‘Roseability’, like ‘Idlewild’, is a compound word, a mashing of nouns that seems to promise deep meaning as its very premise. But where is it pointing us? What of Stein and what of her roses?

Stein’s famous quote on roses, ‘Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose’, seems to do two things. Firstly, it indicates an essentialist perspective on semantics—circularity conveying the uselessness of further description. Secondly, it enacts a qualitative echo chamber by which the reader must question what constitutes this essence, this roseness which is the rose’s identity. The repetition suggests the elusiveness of this essence, deferring with dreamy assertion—the kind of beautiful aphorism you might coin on an acid trip, completely sure of your own new logic. There’s a sense, with every ‘rose’, of meaning’s possibility blooming. You want to wrap the sentence in a circle (as Stein did, selling the phrase on plates) and close a precious loop, devoid of full stops and fixed meanings. Is a rose a rose or the space between a rose and what a rose is? Swap Saussurian triangles for sweet hips and sepals, a new rose budding in the roots. Lose all fixity for the chance trellising of structure, turn attention to sunlight, rainfall, temperature and other environmental conditions. Acquire tautologies and promise of spring. A rose is a whorl, a loop; a delicate head so heady with beauty. Humans like roses share beds sometimes. Look too long into the corolla and maybe you’ll lose your mind.

Idlewild: the secluded meeting place in L. M. Montgomery’s 1908 novel, Anne of Green Gables

Idlewild: the original name of John F. Kennedy International Airport in NYC

Idlewild: to idle wildly; to wildly idle; to idly go wilding.

“You’ll always be, dissatisfied.” Perhaps the mere act of flicking through memories is a form of idle wilding. Making a wilderness of memory’s stasis. Depart only at airports; dwell between continental impressions of kisses.

100 Broken Windows marks a turn in Idlewild’s direction: from their 1990s brit-pop/punk roots to a more spacious, ambitious sound, influenced by the likes of The Smiths, The Wedding Present and R.E.M. When I first started listening to Idlewild, 12 or more years ago in those tender, pre-adolescent times, I sort of filed them as the Scottish version of Ash: they had that punk sensibility coloured by stadium choruses and a cheeky pop strain that balanced the anxious lamenting aspects. All sincerity, sure, but the lyrics were sharp enough to lift them from the sentimental pitfalls of subsequent contemporaries—the end of alt. history that was ‘Hey There Delilah’. Here we move into screaming emo or post-hardcore as inherent hauntology of the fuzzy rock club: the bourbon and sweat, the greasy hair, the frank, shuffling indifference of stoner punters. There were words that smouldered, sparked, then extinguished in the wind; but Idlewild had something different, a primitive attunement to human sorrow that cut through the gum-snapping cool of postmodern irony games, even as its affect blew up in a drumbeat or solo, the loquacious, Michael Stipe angst of Roddy Woomble’s voice. Think sonorous violins and a solid rock chorus, all the energy and wit being typically Scottish. Like the Manics before them, Idlewild did punk and guitar pop, did the stylised mosh and generic fusion, did the political and personal. The millennial malaise in their songs was very much of the times even as it seemed already tired of them:

It’s a better way to feel

When you’re not real, you’re postmodern (It’s not that one

dimensional, it’s not the only thought)

Cut out all feeling, except wait. There’s more. We don’t have to languish in the paralysing grunge of the nineties. The drama of strings would grace each melody electric and maybe you’ll find historic truth in this plugged-in homage to folk turned on its head. If postmodernism is a Mobius strip of self-referentiality, that recursive collapse of linear progress (figured as a Scalextric set in the video for Idlewild’s ‘These Wooden Ideas’), then how to find meaning again, to find sense at all? Stand in a doorway and find yourself blasted with void fill, flick grapes in a wastebasket, count up your demons for the old stoned longing. Shrivel like raisins. The turn of the century has already happened, but maybe if you surrender to the chorus you’ll feel less jaded. There’s a reassurance. The thing about choruses, after all, is that they repeat.

As it does with choruses, algorithms and perennial blooms, repetition happens a lot in Tender Buttons, Stein’s infamously cluttered collection of prose poetics. With repetition and modulation, a queering of standard grammar, everyday objects become less the tools which underpin human existence, and instead things in themselves—the wasteful artefacts in excess of definition. Paratactical, concatenating assemblages which entangle like vines or else accumulate. Grapes on the carpet, styrofoam littering the floor, a word or two oozing through the backdoor…Am I far too close to the things I mistrust? Maybe there is always a stammering, a stilted stilling. I buy roses for the restaurant in which I work and the very act drags me into heteronormative time: the time of expensive dates, birthdays, weddings, funerals, candlelit dinners. What preference for the deep, luxurious, elusive bloom? Must lovers cut their tongues on thorns? I wonder, do those erect stems contribute their strange teleology…to what, to what…are roses always in excess of themselves—showering petals, shedding, being ever so much just roses?

“I stopped and waited for progress”. Back in the day (2005), the NME rated Idlewild ‘a stolid group of trad guitar manglers’, whose new single ‘Roseability’ served ‘both as a rabbit-punch to the head of agnostics and a celebratory three-and-a-half minutes of safe, predictable, wholly generic, utterly brilliant rock ‘n’ roll.’ It makes me dewy-eyed to remember the magazine’s honest, scathing days. That insouciant, throwaway cool. Music criticism was pretty brutal when I grew up, and you basically had to tick every indie rock’n’roll formula (hello Alex Turner: snake-hips, haircut etc) to get consistently decent reviews. Or you could nail the attention on some eccentricity (The Horrors), or perhaps mediocre throwback to rock’n’roll times gone by (need I name every white boy indie suspect circa 2007). ‘Roseability’ is how it feels to be in your twenties, surrounded by people looking backwards; not quite in anger, but in nostalgia. It’s been a long time since I’ve considered something new as ‘utterly brilliant rock ’n’ roll’ in the transcendent sort of way Idlewild pull off—hardcore guitars, thrashing drums, literary references and all. Sweetness and thorns. Uneasy noise secretion. Tip your hat at tradition and then blast through the chorus, scatter your petals to cover the seams. What words in ‘Sacred Emily’ follow the roses? ‘Loveliness extreme’. I miss the NME, I miss being young enough to get lost this easily.

To veer into Idlewild itself, let’s wallow in passages from Anne of Green Gables:

You know that little piece of land across the brook that runs up between our farm and Mr. Barry’s. It belongs to Mr. William Bell, and right in the corner there is a little ring of white birch trees–the most romantic spot, Marilla. Diana and I have our playhouse there. We call it Idlewild. Isn’t that a poetical name? I assure you it took me some time to think it out. I stayed awake nearly a whole night before I invented it. Then, just as I was dropping off to sleep, it came like an inspiration. Diana was enraptured when she heard it. We have got our house fixed up elegantly. You must come and see it, Marilla–won’t you? We have great big stones, all covered with moss, for seats, and boards from tree to tree for shelves. And we have all our dishes on them. Of course, they’re all broken but it’s the easiest thing in the world to imagine that they are whole.

That endearing, childish hyperbole, the absolute thrill of invention. The special grove in a ring of white birch trees, heart of the circle, the rose’s secret pistil. Place of germination. Fragments congeal as expansive imaginings, disappointment evaporates in hope.

“Gertrude Stein said that’s enough”. I’m not quite sure how Roddy Woomble, Idlewild’s lead singer, intended the Stein namedrop, but I take it as a reference to her poems’ weird loops of recursion. In the video for ‘Roseability’, Stein’s portraits are hung up all over the room; her face is even on the front of the kick drum, looking all knowing and stately. The video’s aesthetic has the feel of a 90s television set, all pop art circles whose colour has faded, sharp swivelling camera angles and hair swishes. The pop iconography of teenagers flooding the room with their plastic bracelets, braided hair and awkward moshing. It would be totally American if not painfully, most Britishly sincere—I mean just look at how the guitarist crushes into his own instrument, how Woomble wipes sweat off his face, paces around with the mic so close it could feel his breath. Loveliness extreme. When this was released, I wasn’t even a teenager. When I finally see him live, it’s in a church hall in Maryhill 2k17 and it’s utterly beautiful: how generous the set-list, how gracious a frontman with his small-talk and nods to the band, his thank yous. Watching the kids in the ‘Roseability’ video recreates that weird oscillation between feeling old and seeing in their faces the bizarreness of MTV ennui: the ghost of what I would temporarily become at thirteen, fourteen; cladding myself in discount Tammy girl, then Topshop, dying my hair pink and donning studded collars. With the hormones, you lose that ecstatic childhood imaginary hope; desire is amorphous and endlessly droning. You close your eyes and it seems the world has already ended. Sometimes it comes back, sometimes not. Maybe roseability simply means innocence.

‘Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself’ (Woolf). But customers rarely do. It’s up to me to ornament a room, to flourish a mood, to mark some milestone in another life that’s not mine, whose linearity’s not mine.

My mother bought rose-coloured roses for my eighteenth birthday, blush pink. Red when I turned twenty-one. I stopped acting sweet and rosy, dyed my hair red too. Fell through the whorls, the plush abyss.

‘Roseability’: the ability to be of roses, for roses to exist? Sensibility is, according to my laptop’s built-in dictionary, ‘the quality of being able to appreciate and respond to complex emotional or aesthetic influences; sensitivity’. Does roseability denote a similar sensitivity? When we think of roses we think often of Englishness: that angelic Laura Marling figure, a garlanded Bronte heroin, Paul Weller’s ‘English Rose’. We think tenderness, pastoral, a certain enclosure (marriage, gardens?) and guaranteed loveliness. She who coils golden hair round her porcelain finger, who knows how to talk to sheepdogs, who paints watercolours of the dawn. We think Shakespeare—‘a rose by any name would smell as sweet’. But we also think north of the border, a little bit of the visceral made kitsch: Robert Burns’ ‘my love is like a red, red rose’, whose unfortunate fate is to garnish every dishtowel bought on your granny’s last visit to Alloway (Roddy Woomble, perhaps not incidentally, is also an Ayrshire lad). The faint rose scent in a golden cologne, mingled with tobacco; the glistering sweetness of a youthful, drugstore perfume. Roses are roses, but roses are so many things, are poised on the lips of also…

The rose is a complex flower, a perennial whose species number over 100. Roses are typically ornamental, grown by those who know what cultivation means and spend their Septembers clipping away the thorny remains. An old man round the corner from my flat is out in all weathers among soil and stem: grafting, trimming, tilling for his roses. Perhaps he loves them more than his children. In summer, walking home on warm evenings you can smell them in the pale ambrosial air, a delicate bounty. If properly cared for, roses can live a long time, perhaps over and over, perhaps forever…what exactly does perennial mean?

The appropriately named Bloom, in James Joyce’s Ulysses, stands on Cumberland Street and opens a letter from Martha Clifford—a woman who responded to his newspaper ad requesting a typist. The Dublin postal system facilitates a sort of illicit exchange between them. Half-rhyme, consonance: petal/letter. The delicate thrill of letterly infidelity. She wants to know ‘what kind of perfume does your wife use’; the animal possession of scent. She attaches to her letter a flower, slightly crushed:

He tore the flower gravely from its pinhold smelt its almost no smell and placed it in his heart pocket. […] walking slowly forward he read the letter again, murmuring here and there a word. Angry tulips with you darling manflower punish your cactus if you don’t please poor forgetmenot how I long violets to dear roses when we soon anemone meet all naughty nightstalk wife Martha’s perfume. […] Fingering still the letter in his pocket he drew the pin out of it. […] Out of her clothes somewhere: pinned together. Queer the number of pins they always have. No roses without thorns.

So many compound words, clustering in the mouth like so many attaché petals peeled off from a dress. He plucks them away, fingers the soft excitement of words: ‘naughty nightstalk wife’ with the luridly alliterative twist of fantasy. Libido vs. loss of life. What slips away with the pin? What does the pin pin together? Folds and creases, sleepless. Spike of cactus, nasty, phallic. Prick. Tulip. Coiled anemone: wild flower or tentacular sea creature? Connotations of slip. In her slip. Slippery. Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams, waxing lyrical about female genitalia:

I thought of what seemed to me a venturesome explanation of the hidden meaning of the apparently quite asexual word violets by an unconscious relation to the French viol. But to my surprise the dreamer’s association was the English word violate. The accidental phonetic similarity of the two words violet and violate is utilised by the dream to express in ‘the language of flowers’ the idea of the violence of defloration (another word which makes use of flowersymbolism), and perhaps also to give expression to a masochistic tendency on the part of the girl. — An excellent example of the word bridges across which run the paths to the unconscious.

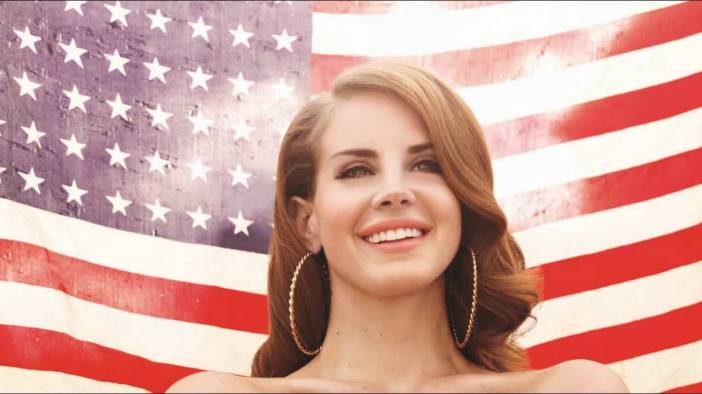

Dear roses dear romance; violets are pale taste of childhood’s sweet naivety. Violets are blue and so are you. Things you can take away. Lines of flight, tangled stems and botanical echoes. Semantics. Lingering taste. The burgeoning rhizomes of the greedy unconscious. Lana Del Rey: “there are roses in between my thighs / and a fire that surrounds you”. The Metro calls it a ‘shocking new track’, but I’ve never heard anything so languid and dreamy and in love. Hungry. Sugar is sweet and…

Angela Carter’s roses bite, don’t you? In ‘The Lady of the House of Love’, the self-starving somnambulist—the ‘beautiful queen of the vampires’—is a figure for desire’s recursive, self-destructive appetite. Manifest as addiction, or withdrawal; the flesh-shedding lust of anorexia, its resistance to growth and fuel. ‘She herself is a cave full of echoes, she is a system of repetitions, she is a closed circuit’. Her dialogue billows round and round into absence. Like Stein’s rose, she is bound to the noun and the grammar of herself—the flickering inward structures of mind, matter. The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. Clustering rootlets, trapped yearnings for impossible perfection. No rose can be the perfect rose; except perhaps Stein’s rose: the virtual rose at the end of the looping rainbow. Loopy, lupin, lupine, luminal. Devouring, emanating, alluring. The virtual rose, perfect by its very impossibility, like Mallarmé’s Book. So many leaves and words. The stain of ink and rain, imprinted teeth. Carter again: ‘I leave you as a souvenir the dark, fanged rose I plucked from between my thighs, like a flower laid on a grave’. Those intoxicating roses, like Carter’s baroque, coruscating prose, cascade across the page, the white snow, the grave. La petit mort. In every petal the promise of a word, a breath.

Roseability. Faith in the unknowingness that is adulthood’s full blooming. Desire’s maturity bound in nostalgia, that noxious plague of your twenties; the ‘sense sublime’ of Wordsworth, five years later, experiencing ‘something far more deeply interfused’. Like the rose’s corolla, time rolls both round and onwards. It’s nauseating, an almost vortex. You’re always chasing that inward spirit, the thing that burns regardless: “They won’t teach you / what you don’t already know”—don’t Idlewild know it?

“There is no roseability.” Enduring, complicated, hungry and sweet, it’s no surprise that roses are symbols for romantic love. Oh hallowed, protected cliché. Expensive hotels strew red roses on white bedsheets, a look that is oddly funereal. Share the ephemeral with melting chocolates. Reminiscent of menses, the blot of a clot in time. He got shot. She bled freely. Blood is like iron, a sharp metallic taste. What do roses taste of? What kinds of symbolic immersion might get at the essence? A bathtub of roses, a bedspread, a bouquet exploding for wedding celebration. Petals of confetti; a blossoming, artificial effect. White roses can be purity, lightness and marriage; or maybe undying love in death, restoration of innocence. I love you as the snowfall that closes Joyce’s ‘The Dead’. Sitting on the languid banks of a river in June, desecrating a rose with your sorrow: one petal, he likes me, two petals, he likes me not. Enough petals to fill a river, all the world’s worth of unrequited love. Red upon red upon blue. Flowing, felt in the blood. But no river is ever twice the same, no rose identical, no inflorescence—despite the algorithmic genius of plants—symmetrical. The beauty of roses comprises their subtly unique detail. ‘Lesser’ flowers, mere ornaments to weeds, clutter up close in mutual similarity. Maybe’s Gatsby’s Daisy could be anybody—she just had to be sweet and blonde, smelling of the damp rich old world, ersatz fresh, ready to decorate. The colourful shirts were mere petals for the true dark rose of his longing. Did Gatsby have blue eyes? I can’t remember.

I did a hard-drive search for the phrase ‘blue rose’ and found an old flash fiction piece I wrote years ago, called ‘Watercolours’. An extract:

The garden fills with new light; conscious light, collecting a clarity not quite recognised. The roses have left their earthly bodies, and the worms burrow up through the untilled soil. The roses’ spirits lift the leaves from the trees and scatter them like sloughing flakes of a giant’s skin. A sigh escapes the sultry violets, the ones he captured once by mixing blue and red. The red poppy is a pretty thing, but she is unborn yet. A mulch of memory overturns as day decides to end.

Isn’t it strange, the seduction of fairy tale ecomimesis? Nature’s ekphrasis surrendering effortlessly to the same saccharine motifs; the kitsch aesthetic containing within its insistence a certain artifice, then the theatrical mists of deliberate illusion. I think of watercolours and I think of everything blurring. Colours decay in the rain, or do they saturate? And again, the roses and violets, whores and madonnas? What of the feminising of botany’s blushing ornaments, ‘captured’ by a (male) artistic vision? But time is ever more flowing, desire afloat, liquid and trembling as rain. What would it mean to anthropomorphise roses, to imbue them with certain abilities? Roseability. These would be the most precious roses, the memorialising and future-making symbols. The blue ones.

I also found a piece from 2013 titled ‘Blue Roses’ It’s about a botanical garden famous for its sky-coloured flowers. The narrator’s lover, Richard, laments the death of his mother and talks about what it would be like to be a carnivore plant. The narrator says: ‘“Those long, slow deaths would suck out your soul.”’ Was I reading Carter at the time? Nature (always capitalise to denaturalise) in this story is narcissistic, strange, devouring: stars are ‘aware of themselves’, the twilight forms deliberate ‘geometric patterns’, the rain ‘spilled out in oozing puddles that clogged the scum of the pavement’. Security patrol the blue roses in the glasshouses. It isn’t entirely clear what they mean in the story. Symbols for what? Eliding natural selection, these monstrous flowers blur into nothing but blueness—the exotic quantity, intangible mystery, possible infinitude. Despite the wholesomeness of the tale, I couldn’t help but think of the weird erotic undertones of its spooky botany. Blue rose, blue movie.

So yes, the very phrase ‘blue rose’ denotes something exceptional in Nature (in Twin Peaks, a ‘blue rose’ case is one which involves supernatural elements). In Tennessee Williams’ play, The Glass Menagerie, Laura (a character based on Williams’ mentally ill sister, the aptly named Rose) is nicknamed ‘Blue Roses’ on account of her fragility, her spiritual affinity with that which transcends the ordinary (and a childhoood attack of pleurosis). Laura dwells in a surreal version of reality; her very nickname harks back to André Breton’s ‘First Surrealist Manifesto’: ‘Cet été les roses sont bleues’ (this summer the roses are blue). Things have reversed and in their delirium remain quite beautiful. Roses, blue or not, are associated with a certain precious wavering between worlds both spiritual and physical; worlds crossed only by rare occurrences of romance, imagination, memory. He loves me, he loves me not…Laura is obsessed with a little glass unicorn, symbol of mythology, virginity. Preservations of the body for another world, or from another world? I go into the woods and find fairy rings made from small white flowers (I think of the inverse fable of extreme depression, the harp-sparkling Manics’ track, ‘Small Black Flowers That Grow in the Sky’). While there is a lovely joy to the common daisy or meadow flower—an ethereal quality that recalls our initiating buttercup crushes—the deep lust of Romance must be associated with the scarlet plumage of the rose. Love is calculated on decadence, exception.

Is a rose as shatterable as glass, as a heart?

I used to live in a house called ‘Daisybank’, but my friends always teased because there were roses painted onto the window, not daisies. What weird reverse supplement? The fat white dog daisies would spring up on the front lawn in summer, but they were always overlooked by those glassy roses. There’s a certain authority, majesty even, to the rose. You associate it with tragedy and great beauty: Lana Del Rey with her lips stuffed full with a rose, playing the calamitous heroine. Snow-White and Rose-Red. Shakespeare’s ‘a rose by any name would smell as sweet’ is taken from Romeo and Juliet, in which Juliet convinces Romeo that it matters not that his name, Montague, is her family’s rival house. A rose is a rose; regardless of name it will always come up smelling of roses. Having graduated from Daisybank, I now find myself living on Montague Street…

‘Who dreamed that beauty passes like a dream?’ This is W. B. Yeats, probably writing to a woman he loved, Maud Gonne. He seems to set up beauty as life’s eternal opposite; where human existence is fleeting, beauty remains archetypal, enduring. Think of Keats’ ‘beauty is truth, truth beauty’. There’s a universality, a mythological underpinning to this beauty. In Yeats’ poem, the loved one embodies wistful figures of glory: Helen of Troy and Usna of ancient Irish history. Surely she slips between the shadows of comparison? Whether Yeats scorns the idea that beauty ‘passes like a dream’, or whether he ultimately reveals its truth, is unclear.

For Immanuel Kant (see, Critique of Judgement), the experience of beauty hinges on a paradox: since it seems that beauty is a property of the object—indeed, emanates from it—you’d think beauty itself was universal. Everyone should fall in love with that painting, that colour, that song. But not everyone does find the same things beautiful. It feels like a betrayal of reality when I play Radiohead’s ‘True Love Waits’ (where roses are swapped for “lollipops and crisps”) to a friend and their reaction is a casual ‘meh’ and a shrug, while all sorts of biochemical reactions of wonder and euphoria are swirling around inside me. Beauty, for Kant, is largely nonconceptual: that is, there’s an unspeakable quality to it, a thing you can’t put your finger on. In Realist Magic, Timothy Morton describes it as beauty’s ‘je ne sais quoi’. Being unable to pin down what it is that makes a thing beautiful is part of its beauty. You take a rose. You could describe its petals, its inward swirling whorls, its scarlet colour, the slenderness of its stem; but in doing so, you lose the rose itself. As ever in synecdochically applauding a woman you lose the woman. The love object. The love? Recall Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 116’? ‘Love is not love’; it’s what it is and it isn’t, and what’s left over as forever. 4Eva/4Real. Personally, I prefer Cate Le Bon’s take: “Love is not love / When it’s a coat hanger / A borrowed line or passenger”. But isn’t everything stolen and temporary, in transit? How do you claw back the rose when the rose, maybe, is just this epic symbol for love? What moves in the static eternity?

I used to draw roses all the time; I’d always start in the centre, finding my way outwards with liquid ink. You see I had no conception of the rose’s shape, I was just following the shaky trajectories of layering lines. Important not to excise too sharply the arrangement of beauty, to impart onto nonhuman forms a reified taste. Eroticism preserved by ellipsis, meditation contained in the mysterious code of the senses. What was it Wordsworth said so long ago, in his famous tract against book knowledge: ‘Sweet is the lore which Nature brings; / Our meddling intellect / Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:— / We murder to dissect’. Wordsworth would prefer you to go out and encounter the objects themselves rather than try to ‘dissect’ them through rapturous, scrutinising poesy. Being one of the great Romantic poets, distracted by words even when in Nature, Wordsworth is of course a filthy, (forgivable) hypocrite—up to his knees in Kant’s paradoxical beauty as much as the rest of us.

Making words of roses involves cutting their heads off, losing the essence, letting the adjectival rose oil leak into language’s dripping pores. Binding the immortal to time. That seepage is ink, is tense’s durational flow, is poetry’s cruelty. This is perhaps what Mallarmé means when he says: ‘Je dis un fleur, et le fleur est parti’—‘I say a flower, and the flower is cut/split/gone’ (translation: Tom McCarthy). To break the object of beauty down in writing is to incur a violence; as McCarthy glosses, ‘Things must disappear as things in order to appear symbolically’. What is perhaps most seductive is the remaining qualities, the deconstructionist’s milk and honey, the semiotic residue that clings between things. Spiderwebs, woven by first light, acquire a serene and gossamer gleam; but what is most seductive perhaps is the spaces between the lines, the way up close the lacing makes new frames for the real, the scenery behind and through.

Then we have Derrida’s ‘maddening’ supplement. For all roses refer to other roses, to every iteration of the word ‘rose’ throughout literary history. What a rose means can only lie in the space between these occurrences, and even then the meaning is temporary, contextual—there is no outside text, no place in which to hurl your roses to semantic abyss. We might hope for Love as some manifestation of the Lacanial Real, a pre-symbolic realm of pure emotion; but love too (as Roland Barthes reminds us) is discourse, perennial and yet bound to the fluctuations within language. ‘Rose’ is a noun, but it is also qualia: the subjective quality of something that cannot be objectively measured. Her cheeks were rosy, the rose-coloured sand (of the dream sequence in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film, Red Desert), a rosiness to the air that spoke of July. By scaling tone, we might get a general sense of what ‘rose’ is (a quality defined by difference rather than identity), but we’d never get to see rose through someone else’s experience. What is ‘rose’ to one poet might be ‘pale and bloody’ to another. Rimbaud writes, ‘The star has wept rose-colour in the heart of your ears’. Abstraction meets the concrete which itself is a spill through synecdoche. What music seeps, weeping, into the beloved’s ‘ears’? ‘Rose-colour’ becomes that synaesthetic property, the oozing, effulgent thing that cannot be pinned. For colour, like music, is perceptively subjective. What prompts a sudden spasm of imagining in you might send me to sleep; could we call both actions reactions to beauty?

‘It’s hard to stay mad when there’s so much beauty in the world’. So goes the line in American Beauty, Sam Mendes’ 1999 suburban modern classic—a film about midlife crisis, inappropriate lust, neurotic materialism and the nuclear family under late capitalism. Where Ricky, the visionary, weed-smoking teenager, sees a sort of sublimity in waste, videoing a plastic bag’s leaf-like billows in the wind, Lester falls for his daughter’s cheerleader friend, Angela. The particular Gen X fatigue over cultural trash and consumer excess is recycled as a pared-back appreciation for symbolic indications of the world’s decay—little quotidian details which offer momentary redemption as beauty in tragedy. The old Kantian adage of beauty’s je ne sais quoi. Lester’s misplaced infatuation for Angela is represented by motifs of lurid red roses, flowering outwards like bloody snowstorms of feminine intensity. The chase falls cold when they kiss IRL, and he realises she is just an insecure teenage girl. Tell me I’m beautiful. Interpreting the film is as tricky as trying to clasp onto any one of those whirling petals, to kiss a single tear on an eyelash, a dew-drop clung to the flesh of a rose. Joni Mitchell, in ‘Roses Blue’: “I think of tears, I think of rain on shingles / I think of rain, I think of roses blue”. A lyricist’s ability to make pearls of emotion. Superhydrophonic. Is this another symbol, listless, transient, glistening?

The Symbolists were mostly French poets of the fin-de-siècle, the likes of Rimbaud and Baudelaire (whose flowers were assuredly evil), who probably drank quantities of absinthe and wrote symbols that emblematised reality itself, rather than merely inward feeling. All that absinthe had to come out somewhere, idly wilding in the streets of Paris (pronounce it the French way). Where abstraction reigns often in the world of emotion, meaning accumulates through the repetition, modulation and pattering of these symbols. While Mallarmé’s poetry indulged in dreams and visions, it’s a certain patterning of associative power that provides the stitching behind his fashion for aleatory. The poetics of chance may still have a structure of sorts, something you can trace like the veiny trellises within a leaf. W. B. Yeats, the Irish Symbolist, loved a good rose: just see ‘The Rose of the World’ and ‘The Rose of Battle’. In his essay, ‘The Symbolism of Poetry’, Yeats makes frequent comparisons between symbols and music, describing the ‘musical relation’ of sound, colour and form as constitutive of symbol.

At a workshop I’ve been running with homeless people, a girl who shares her name with Stein’s favourite flower reads out a piece she’s written in ten minutes flat. It’s a typically tragic tale of abuse, of a family torn apart by pain, drugs, death and violence—written from the perspective of a ten-year-old girl, perhaps her daughter. She reads it with a stilted west coast accent that picks up its confidence and lilt as the sentences run on. Somehow in those sad and wilting lines, strewn with the accidental detritus of truth, there’s hope. It blooms so unexpectedly in all the despair. A ten-year-old girl sees the world very clearly and pure. I can only paraphrase, of course. I’m sad that I don’t get to see my mother, but she says that it’s okay because if I look at the moon I know that she’s looking at it too. This part struck me harder than any other—it seemed an echo from elsewhere. The whole piece became suddenly a buildup to that single, simple, irresistible image. When Yeats presents Burns’ ‘perfectly symbolical’ song of the moon and time, he misquotes him. Translation falters to glitch, like with lossy compression. The moon as a symbol, as something to be shared, a white chocolate button broken in two. Except you can’t split the moon. You can only imagine what the other person is seeing. I wonder what they were looking up to.

Where metaphors ‘are not profound enough to be moving’, symbols move in both senses of the word: they act through motion, the accumulative or associative arrangement of sound and meaning (as opposed to metaphor, which acquires meaning through more static, straightforward comparison), and they prompt affect in the reader. Such affect is not just the temporary indulgence of an artwork’s emotional value, but can indeed alter how the world is discursively understood. The rosy words thrown upon some poetic zephyr recalibrate reality as we know it. As Yeats puts it:

Because an emotion does not exist, or does not become perceptible and active among us, till it has found its expression, in colour or in sound or in form, or in all of these, and because no two modulations or arrangements of these evoke the same emotion, poets and painters and musicians, and in a less degree because their effects are momentary, day and night and cloud and shadow, are continually making and unmaking mankind.

The construction of feeling through symbols, then, institutes the substance and gaps that structure how we relate to ourselves, others and nonhuman objects. A very delicate, precise, imagist poem like William Carlos Williams’ ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’ has effectively changed how we relate to both the colour red and wheelbarrows more generally (never mind the ‘white / chickens’). Symbols can charge our perception with fresh emotional channels. Music relates a bit differently, of course, but only because it literalises Yeats’ musical relation metaphor—there’s a more physical intensity, maybe. Like a river (you can never dip your finger twice in the same river), a piece of music cannot be played the exact same way again—a truism owing to the arbitrary dynamics of individual players, environments, acoustics or subtle interruptions of duration. A breath or a sneeze, a chance sigh in the background, a trumpeter who can never quite pace her crescendo. You experience the opera differently from me, even though we watch the same one (I have never been to the opera). My hearing is slightly muted, along with my interest in self-congratulatory coloratura; while you have perfect pitch, ears that ring with pleasure as the high notes hit. Though the same in one sense, comprising a shared duration, our encounters are completely different. Music’s durational function is made explicit with the likes of John Cage’s music concrète, composed of sounds rather than notes and thus retaining elements of chance within a certain duration. The process becomes more about selection, sampling and curation, rather than composition according to tones, melody, chords.

If anyone idled wildly, it was the notoriously languorous aesthete, Oscar Wilde. The decadence of roses is also associated with a certain concretisation of language, a making material of words, a honing of time and world. Consider the opening line of The Picture of Dorian Gray: ‘The studio was filled with the rich odour of roses’. The way assonance works, subtly wafting its chiming vowels through ‘filled’/‘rich’ and ‘odour’/‘roses’, creates that musical relation that Yeats so fetishised. Poetic techniques such as alliteration and assonance abound in Wilde’s novel, where prose becomes musical, lilting, exactly honed upon sensory detail, the vivid relation of objects. Roses that fill a studio, that pungently glow with lavish scent. There is a heady, ambient quality to much of Wilde’s descriptions, giving off the impression that we are perhaps perceiving how objects seem to one another, filtered through the opium vapours that so penetrated Dorian’s accelerating decadence: ‘In the slanting beams that streamed through the open doorway the dust danced and was golden. The heavy scent of the roses seemed to brood over everything.’ Objects are at once anthropomorphised and ornamental; that play between movement and stasis, however, cuts across binaries between human and nonhuman. The world of Dorian Gray is sprawling, random, a chase through meshes of entangled desire. A straightforward death drive is diverted by all sorts of sensory encounters, plastic morality, visionary beauty. And words? Words in Wilde are the petals that swell and unfurl into Yeatsian symbols:

Music had stirred him like that. Music had troubled him many times. But music was not articulate. It was not a new world, but rather another chaos, that it created in us. Words! Mere words! How terrible they were! How clear, and vivid, and cruel! One could not escape from them. And yet what a subtle magic there was in them! They seemed to be able to give a plastic form to formless things, and to have a music of their own as sweet as that of viol or of lute. Mere words! Was there anything so real as words?

Words have (re)active potential. Each one shivers with the weight of its every use, alive with subtle magic. Be careful what you write.

“Gertrude Stein said that’s enough (I know that that’s not enough now)”. Gertrude Stein said a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose. She said it first in ‘Sacred Emily’ (1913), and later wrote, in ‘Poetry and Grammar’:

When I said.

A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.

And then later made that into a ring I made poetry and what did I do I caressed completely caressed and addressed a noun.

What do we swap for tautologies? Love is tautological; love justifies itself. It means everything and nothing. There’s isn’t any escaping the reifying loop, the ring with its symbolism of marriage. That which encapsulates and closes. The hermeneutic circle. Stein makes us linger, ponder the grammar of each rose. Ring-a-ring-‘o-roses. What does it mean to ‘caress’ a noun? To render the erotic potential of language by gesture of touch, extend into physical… Idlewild: a word whose internal rhymes fold together, whose l sounds caress the roof of the mouth.

“Gertrude Stein said that’s enough.”

Lana Del Rey: “You always buy me roses like a creep.”

Also Lana Del Rey: “And then you buy me roses and it’s fine.”

There’s a surfeit of petals and sex, a gluttonous economy of symbols which Stein stamps out with the simple carousel of her musical roses. Sing it slowly. Tell me what you mean.

Luce Irigaray, from This Sex Which Is Not One:

Your body expresses yesterday in what it wants today. If you think: yesterday I was, tomorrow I shall be, you are thinking: I have died a little. Be what you are becoming, without clinging to what you might have been, what you might yet be. Never settle. Leave definitiveness to the undecided; we don’t need it.

Lana Del Rey, reading from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets:

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden.

I pass between worlds and names and symbols. Every lipstick stain is another iteration, each kiss the palimpsest of the first, and even photographs fade in the sun, faces dissolving like planes behind clouds. Of ‘cappuccino pink ranunculus’—not roses—Colin Herd writes: ‘They’re at their most ravishing and / ethereal the day before they expire’. I imagine a white corridor imprinted with all your flickering dreams. Between realms, the soft wilt allures more even than it does in bloom. Images become sentences: long thorny stems of sentences, stretching and snarling a confusion of brambles and briars. The more you write, the more you grow your beautiful garden. I tear my wrists and fingers, trying to get to it: ‘There is a forcible affect of language which courses like blood through its speakers. Language is impersonal; its working through and across us is indifferent to us, yet in the same blow it constitutes the fibre of the personal’ (Denise Riley). This garden I make is not really mine and daily it grows stranger. The roses offer their pretty heads, then droop in winter. I hear their beautiful words in arterial melodies, sprawling among shadow, platitude, the skeins of a letter letting loose through my pores.

Roseability: the quality of forever chasing roseability. File under qualia, noun/rock, the poetics of etcetera.