Analysis/Review: Roddy Hart’s 17th Annual Gordon Lecture and the Contemporary American Lyric

What a treat to listen to a lecture sprinkled with songs and stories, especially among the beautiful acoustics of Glasgow University’s chapel. After a rather spectacular introduction from Professor Simon Newman, singer-songwriter Roddy Hart gave the 17th Annual Gordon Lecture, organised by university’s Andrew Hook Centre for American Studies. Having collaborated with Kris Kristofferson, released an EP of Dylan covers and found success in the States with a stint on Craig Ferguson’s Late Late Show—not to mention running his own radio show for BBC Scotland and hosting Celtic Connections, the BBC Quay Sessions and the Roaming Roots Revue—Hart was well qualified to talk on this subject from a musician’s point of view.

Hart’s talk was a tribute to the great American lyric; to what makes it, in Hart’s words, particularly alluring, otherworldly and cool, especially to those who grew up outside of the United States. Admitting that he lacks an academic education in the history of American culture and music (actually, Hart has a law degree gleaned from within these very walls), Hart made up for this by sheer enthusiasm, celebrating the musical merits of songs from Woody Guthrie to Father John Misty and covering such topics as the journey motif, humour, darkness, nostalgia, politics and death. The talk took the form of a powerpoint, with Roddy speaking, singing snippets of songs and then commenting on their significance in a lucid, passionate way that kept everyone hooked for an hour and a half.

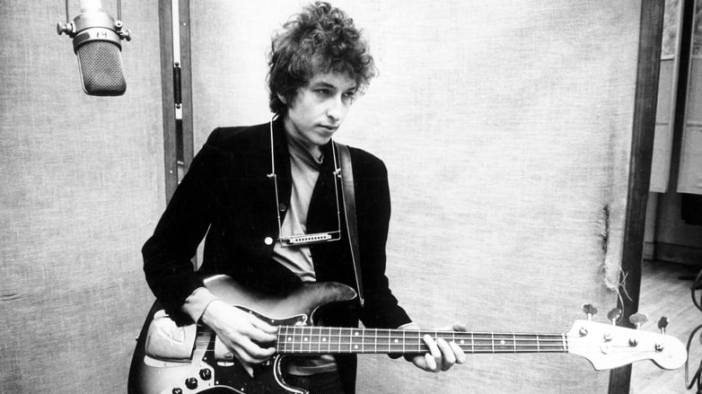

Hart began with the assertion that lyrics are not poetry, or indeed literature of any kind. Lyrics, he claimed, involve respect for structure, rhyme, metre and field (all definitions you could apply to poetry…), a certain knack for a hook, a streak of ingenuity and originality. Like poetry, a great lyric can reshape how we view the world we live in, send ripples through the fabric of reality and inspire us to take action, critically reflect or wallow in grief. The distinction Hart draws between poetry and the lyric prompted a desire to find out what exactly his thoughts are on Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. My own thoughts on this issue have never rested on a single position, and I don’t really know enough about the prize’s history to comment on Dylan’s suitability. However, there have always been strong connections between lyricists and poets, from the likes of Langston Hughes writing jazz poems during the Harlem Renaissance to Kate Tempest releasing rap albums as well as a novel and poetry collections published by the likes of Picador and Bloomsbury, no less. Hell, what about Leonard Cohen? At the end of the day, all writing is a performance of sorts, regardless of how it’s delivered. I could talk about Roland Barthes here, mention ‘The Death of the Author’, how the reader ‘performs’ the text like a score of music etc etc, but I won’t digress. Basically: sometimes a poem seems built for performance; other times it rests more easily on the page, where the eye follows an intriguing visual form or dance of letters arranged on white space. While poetry can be a two-way street, I’m not sure how well Dylan’s verse works on the page. Admittedly, most of his songs tell interesting stories, but that deceptive simplicity often needs the nuance and expression of Dylan’s voice to draw out the subtler levels of irony, humour, derision or sorrow from straightforward-seeming lyrics. Just my two cents on the matter, though I still like to wallow in ambiguity when it comes to these distinctions.

Hart gives the proviso that his talk is meant to be a working definition of the American lyric, not a comprehensive history. He does, however, mention a few characteristic features. The prominent one, of course, is name-checking: all the best American lyrics will draw on the wealth of states, street names, famous bars and hotels. In doing so, they draw on a tradition, they write themselves into a history of locations, urban legends and folk tales. Hart illustrated this by starting with Paul Simon’s ‘America’, pointing out how the song documents a search for America itself; this idea that America will always be this endless signifier, sliding along the great highway of desire that stretches across desert, country and city, drawing across generations. On the way, the lovers in Simon’s song make the best of their adventure, cooking up stories from the characters on the Greyhound, honing in on material details. It’s this sense of taking the listener on a journey that’s one of the American lyric’s greatest seductions. As Simon sings, “it took me four days to hitchhike from Saginaw” the chords soar and there’s that sense of being lifted to somewhere radically elsewhere, an open field, road, desert. The sweet spot between freedom and sorrow, of missing something deep and mysterious, the impossible pursuit.

Hart traces such material details in songs by Kris Kristofferson and Dylan, this sense of a ‘quintessential American aesthetic’ which he quite eloquently describes as a ‘Moby Dick-esque hunt across America’. The whale, ironically, is America itself. The road narrative is central to the American lyric. It’s a romanticised, extravagant sprawl into the dust of the past and glitter of the future, marked by place names which glow with familiar warmth and legendary spirit. Hart argues that this is something specific to the American lyric; that a Scottish equivalent wouldn’t quite have that same epic effect. He even sings a made-up local spin on ‘America’ to prove it; a journey between Edinburgh and Dunoon falls pretty flat in comparison. Of course there’s something special about the land of the free, in all its bright mythology and promise, but it’s not as if Scottish bands haven’t tried it. There’s that famous line from The Proclaimers’ ‘500 Miles’ which immortalises an array of parochial towns ravished by Thatcher, deindustrialisation and eighties recession: “Bathgate no more. Linwood no more. Methil no more. Irvine no more”. Of course there isn’t the same expansive magic, but there is something epic about lyrically connecting the local to broader political discontent. Still, you can’t really compare the Proclaimers to Simon & Garfunkel…or can you?

Back to America. Hart describes Dylan as the nation’s great scene-setter, effortlessly drawing a sense of the times from the wisping drift of personal narrative, of stories about people and their lives. Details shuffled together like cards and strung along a line of verse. While some singers make their politics clear in the didactic manner of protest, Dylan sets these more intimate tales against the backdrop of cities and an impressionistically vivid sense of history. Hart plays possibly my favourite Dylan song, ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ from the 1975 album, Blood on the Tracks, spending time going over the lyrics to point out the singer’s knack for detail, the narrative journey which documents a succession of relationships, places and jobs. That famous philosophy: you’ve got to keep on keeping on. There’s something more raw here than the cosy, apple-pie fuelled comforts of Kerouac’s road narratives, which always depend on money from back home. You can hear it in the howl of Dylan’s voice, which becomes more a sultry croon in Hart’s version. What does he mean by blue? There’s the blues, there’s the blue of the sky and the ocean—symbols of infinitude. It’s a signifier that shifts as easily as Dylan’s character, from fisherman to cook, as he crosses over the West, learning to see things “from a different point / of view”. Surely this is one the basis for democracy, the meritocratic ideal of fairness upon which the USA was founded: empathy? The ability to openly shift your perspective, to never stay too long in your own shoes. That existential restlessness, set against the backdrop of a shaky political atmosphere, the dustbowl sense of losing one’s bearings in a maelstrom of uncertainty, characterises many of Dylan’s songs and indeed many road narratives throughout literature and American lyric.

You can’t talk about the American lyric without mentioning politics and Hart documents the history of the protest song, from Woody Guthrie’s ‘This Land is Your Land’ to Tracy Chapman’s ‘Talking About a Revolution’: songs that pose an equality of belonging, that document the quiet desperation and struggle that takes place beneath the surface of everyday life. Rather than tangling himself in the barbed reality of contemporary politics, Hart opts to situate his chosen songs in the context of more general themes: the failings of the American dream, social inequality and the oppression of working people, all set against the turning tides of the economic landscape. It’s notable that most of these singers are men, singing about working men, often with reference to some vulnerable lost girl who needs saved. But then you have the likes of Anaïs Mitchell, writing visceral songs of longing and misplaced identity. ‘Young Man in America’ opens with this mythological, sort of monstrous story of birth: “My mother gave a mighty shout / Opened her legs and let me out / Hungry as a prairie dog”. Images of industrial decline, capitalist opulence and landscapes both mythical and pastoral are woven by a voice whose identity is a mercurial slide between human, animal and disembodied call. Skin is shed, belonging is only a shifting possibility. It’s a complex song, with native percussion, brass; moments of towering climax and soft withdrawal. The music mirrors the strange undulations of the American journey from cradle to grave, its dark pitfalls and glittering peaks, the cyclical narratives of the lost and forgotten; the “bright money” and the “shadow on the mountaintop”, the fame of the “young man in America”, a universal identity disseminated across a range of experiences. For this is the myth of the American Everyman, and Mitchell deconstructs it beautifully.

On the subject of female songwriters, I was very pleased that Gillian Welch and Lucinda Williams got a mention in Hart’s talk. The self-destructive sentiment of Welch’s ‘Wrecking Ball’ reminds us that the experience of being ground down by the relentless demands of a marketised society isn’t confined to men alone. Welch’s ‘Everything is Free’, not mentioned in the talk though highly relevant, makes this clear. It’s a song about artists will go on making their art even if they won’t get paid, and the tale of how capitalism discovered this and cashed in on its fact: “Someone hit the big score, they figured it out / That we’re gonna do it anyway, even if it doesn’t pay”. Like Dylan, Welch finds herself winding up on the road, working in bars, working hard and regretting being enslaved to, well, The Man. ‘Everything is Free’ is a message of both despondency and hope, crafting this sense of the beauty of song itself as protest and freedom even as the structure closes in: “Every day I wake up, hummin’ a song / But I don’t need to run around, I just stay at home”.

Hart mentions how the American lyric provides an escape to those who find themselves trapped in the smallness of their lives. You might live in a nondescript town slap-bang in the middle of Scotland, where the musical climate favours chart music blasted from bus-stop ringtones, but then aged fourteen you discover Dylan or Springsteen and suddenly America opens up its vast, sparkly vista, from East Coast to West. This seems to be Hart’s trajectory, as his career—from the first tour with Kristofferson to his continued promotion of transatlantic connections—closely follows an American strain of songwriting. My mum used to listen to Welch’s Time (The Revelator) album over and over again on long car journeys, so the lyrics to all those road songs are burned in my brain like tracks in vinyl, superimposed with endless visions of the M8 stretching out before me… It was only a couple of years ago that I found out Time (The Revelator) was released in 2001; I’d always assumed this stuff was ancient, the seventies at least. Maybe because Welch just has this knack for writing timeless songs; songs about heartbreak, loneliness and restless desire that reach back into the comforts of the past even as the journey itself is long and hollow, the destination vague as the blurred sign on the front of a train.

I guess this raises a broader question which Hart’s talk touched upon: the politics and poetics of nostalgia. There weren’t opportunities for questions afterwards, but if there were I might have asked Hart whether nostalgia is a necessary condition for American self-reinvention. It’s a pretty relevant question right now, with much of Trump’s whole appeal based on the nostalgic vision of a vaguely industrial golden age of capitalism—a vision which is obviously the smokescreen for whatever chaotic ideologies are at work beneath the surface. The American lyric can set up this romanticised vision, only to break it apart; reveal its seedy underbelly, its failings, the disastrous gap between identified goals and actual means of attainment. Yet throughout the cynicism, there’s always that restless desire to continue, to keep on keeping on. Hart compares it to the green light in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), a novel significantly indebted to music (jazz, of course). The final line of that novel captures that past/present lyrical impulse so well: ‘so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past’.

Which leads to the question: what about genre? Is the American lyric necessarily the domain of indie folk rockers? What about commercial music and pop? Can a pop artist deconstruct the American dream and earn a play in the lyrical family tree if they make money off their record and earn fame from MTV? Hart engages with Father John Misty as an example of how the American lyric can use humour to deconstruct the nation’s ideologies of progress and meritocracy, at the same time as retaining a post-postmodern self-awareness of identity politics, a meta-awareness of his own dabbling in ironic coolness. His very name evokes a sort of New Age gospel figure, a preacher for the times, whose stage is the television set or Twitter feed instead of the old-fashioned soapbox. Hart describes songs such as ‘I’m Writing a Novel’ and ‘Bored in the USA’ (obviously a riff on Springsteen’s classic) as depicting the ‘American dream for the millennials’. I’ve written about Misty extensively already on this blog (specifically, on his metamodernist tendencies), so I won’t go into detail here, but suffice to say I agree that FJM represents something special about contemporary cultural critique. It’s that blend of irony and sincerity, an exaggerated interrogation of the romanticism and the Gen X postmodernism of yore; the oscillation between raw subjective experience, political critique and the cool facade of self-deprecating wit. A constant juggling of ‘candour and self-mockery’, as Dorian Lynskey puts it. FJM notoriously got into a tiff during an interview with Radio 6 Music veterans, Radcliffe and Maconie. Aside from all the awkward sarcasm, what strikes me about this interview is the mentioning of kitsch merchandise objects: oven-gloves, jeggings. Hart explores a bit of kitsch lyric in the likes of Randy Newman, but I think FJM blends especially well that jaded sense of millennial despondence alongside tracks that can feel like rollicking simple narratives or epics of history on a 13-minute scale that gives Springsteen’s marathon tunes a run for their money. He pushes his stuff to the edge of the cheesy and cringe-worthy, exposing how all conviction has that shadow side of kitsch, even the most authentic lyrics—kitsch is somehow the cheap taste of someone else’s experience, the trick is to make it meaningful, and not just another imitation, a plastic model of the Empire State Building.

But Misty isn’t the only singer-songwriter deconstructing the American dream, exploring how both its poetic promise and jingoistic glory play out on a personal level. What about Ryan Adams, whose songs have that alt-country appeal of the restless bard? ‘New York, New York’, from his 2001 album Gold, opens with a Dylanesque lyric about shuffling “through the city on the 4th of July”, brandishing a “firecracker” that’ll break “like a rocket who was makin’ its way / To the cities of Mexico”. The clean rhymes and ballad-like lilt of guitar are also very Dylanesque. But at some point I’ve got to stop making comparisons to Dylan, because ultimately this is reductive; it’s cheap and lazy music journalism. I do think, however, the ease with which we make these comparisons reveals something interesting about our generic assumptions. Guy has a guitar, sings melancholy songs about America and his place within it, a smart knack for a lyrical twist, occasionally picks up a harmonica? Instant Dylan; their careers overshadowed by a giant. (Note: I guess a similar thing happens with very talented female folk singers—the likes of Laura Marling—being compared to Joni Mitchell). But even Dylan doesn’t monopolise the American lyric. He might have a Nobel Prize, but this doesn’t crown him King of the Lyric Alone (or maybe it does?); we’ve got to tease out what exactly we mean by this term and how relevant it is in the fragmentary scene of contemporary music. Think with Dylan, but beyond Dylan.

Conor Oberst, formerly of the band Bright Eyes, is an artist who’s been branded with Dylan comparisons throughout his career (an extensive career at that; the precocious Nebraskan recorded his first album, Water, aged just 13). Sasha Frere-Jones in the New Yorker condenses many of my own feelings on the Oberst/Dylan comparisons: ‘Dylan is armour-plated, even when singing about love; Oberst is permanently open to pain, wonder, and confusion.’ Oberst is in many ways a liminal figure: cutting it out on the folk and country circuit (Emmylou Harris and Gillian Welch appear on previous records) while hanging and collaborating with indie rock bands (The Felice Brothers, First Aid Kit, Dawes), flirting with punk (The Desaparecidos) and fitting with some comfort within the elastic nineties/noughties stratosphere of emo. Frere-Jones describes Oberst as a ‘poet-prince’, again opening debate on that binary between poetry and lyric that Hart sets up but that nonetheless remains slippery and problematic. Where Dylan espouse the solid wisdom of a sage or wandering bard, Oberst has a reticent, warbling quality that rises to epiphany but admits failure and the graceless fall into existential aporia. He wails like Dylan wails, but many of his songs have a fragility and surrealism that doesn’t quite match up with Dylan’s more assured narrative balladry. So in that sense, he’s a lyric poet in the more subdued, Keatsian manner, exploring the self in all its fragmentary, perplexing existence.

But he’s also very much an American lyricist. In his ‘mature’ career, Oberst hasn’t shied away from more directly tackling political themes alongside more personal songs. 2005’s ‘When the President Talks to God’ rips to shreds George W. Bush’s policies. Comprising a series of questions addressed to an audience, it more closely follows the form of a traditional protest song, laced with bitter satire: “When the president talks to God / Do they drink near beer and go play golf / While they pick which countries to invade / Which Muslim souls still can be saved?”. This is definitely a song to be performed, on a wide open stage or indeed to the even wider audience accessing broadcasts of The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, where he performed the song in 2005. Then there’s the angry, crunchy southern kick of ‘Roosevelt Room’, off Oberst’s solo record, Outer South (2009). Oberst’s later work isn’t as playfully weird and surreal as his early bedroom stuff, sure, but increasingly he masters the power of allusion that characterises American lyric, in Hart’s sense of the term: “Go ask Hunter Thompson / Go ask Hemingway’s ghost”. He’s addressing someone to be critiqued, wrenching them off their political pedestal: “Hope you haven’t got too lazy / I know you like your apple pie / Cause the working poor you’ve been pissing on / Are doing double shifts tonight”. There’s that apple pie again, symbol of steadfast Americana, fuel of the nation, the well-lighted place of a diner—a place of domesticity, stability and, let’s face it, commercial comfort. Oberst cynically dismisses the well-nourished white middle class politician, recalling a generalised story of poverty from material details: “And I’d like to write my congressman / But I can’t afford a stamp”.

Then there’s the frontier motif, the sense of America as a place of deep mystery as well as self-created landscape. Experiments with Eastern and Navajo cultures. Bright Eyes’ 2007 album, Cassadaga, with its album art requiring a spectral decoder to be fully appreciated, its envisioning of the singer as mystic or medium, channelling psychic forces through song. Cassadaga is very much a journey. The opening track, ‘Clairaudients (Kill or Be Killed)’ involves an extended spoken word sample of some kind of very American mystic who begins by setting us in the ‘centre of energy’, Cassadaga’s ‘wonderful grounds that have vortexes’, moving us through astral projections of a ‘new era and life’ that is changing, a message of hope, doubling back on the uncanny sense that ‘Cassadaga might be just a premonition of a place you’re going to visit’. Cassadaga is a real place, a spiritualist camp set somewhere between Daytona and Orlando, known as the ‘Psychic Capital of the World’. By naming his album Cassadaga, Oberst isn’t just name-dropping in typical hipster fashion, honouring local identity nor casting back nostalgically to a familiar place; he’s attempting to channel the energy of this location, interrogate its spirit, draw out its various psychic possibilities for the present. He sings of attempts to detoxify his life, of former affairs, of lost soul singers and the pursuit of a sense of belonging.

‘Lime Tree’ is one of the most beautiful songs Oberst has written. It’s a composite tracing of impressions drawn from various experiences, both personal or secondhand. While much of Cassadaga follows an upbeat, distinctly country sound in the manner of 2005’s I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, ‘Lime Tree’ closes the record with a dreamy, wistful serenity that recalls the likes of ‘Lua’, ‘Something Vague’ and ‘Easy/Lucky/Free’. Accompanied by angelic female vocals, ‘Lime Tree’ is ethereal, the guitar strumming minimal though following a certain continuous loop. Pale and lush strings contribute to the sense of being pulled downstream, giving yourself up to the languorous current. Ostensibly, it’s a song about abortion, about a struggling relationship: “Since the operation I heard you’re breathing just for one / Now everything’s imaginary, especially what you love”. But as in all good poetry, the beauty of the lyrics on ‘Lime Tree’ is their movement from specific experience to a vaguely spiritual voyage that gestures towards ending but instead finds the open plains of abyss, always suspended in paradox and ambiguity, the fault-lines between life/death, hope/despair, dream/reality: “So pleased with a daydream that now living is no good / I took off my shoes and walked into the woods / I felt lost and found with every step I took”. Home is a tidal wave, a churning wind, a shifting sand, a fragment.

America’s great confessional poet, Sylvia Plath, also explored mysticism, and her writing is rich with strange imagery, not to mention all those Tarot allusions in Ariel. In The Bell Jar (1963), the fig tree is the novel’s dark and mysterious heart, this vivid image that sprawls its symbolism through the text, a figure for existential paralysis: ‘I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story […] I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose’. We might think of the connection between the term ‘roots’ and ‘roots rock’, its rhizomatic sprawl of influence never quite settling on a home even as a sense of home and locality is supposedly the music’s grounding purpose. Roots, of course, are always growing. The lime tree is an image plucked from a dream, but its significance is less clear in Oberst’s song than the fig tree in Plath’s narrative. Perhaps more than most contemporary songwriters working within a lyric tradition, Oberst is content to write from a position of uncertainty, in gaps and pieces of affect and narrative. The sound of his voice suspended over those gentle strings and strums is enough to make tremors in your chest, as if the slow vortex of another world were opening its mouth like the parting of the sea in someone else’s biblical or drug-enhanced dream: “I can’t sleep next to a stranger when I’m coming down.” The way of the lyric; so often the way of the lonely. Even as ‘Lime Tree’ might be a love song, it opens itself towards ending, loss, death: “don’t be so amazing or I’ll miss you too much”; there can never be plenitude in the journey: “everything gets smaller now the further that I go”. Bittersweet doesn’t quite cut it. It’s too subtle for that, a softly shimmering lullaby goodbye to the world, a retreat and a return, just like Nick Carraway’s vision of beating on but back into the past. The passage of an everyday spiritual pilgrim, the way we all are in life, our faces fading in the ink-blot of photographs. We turn back to look at ourselves through others, through words, just as Dylan notes how the girl in the “topless bar” “studied the lines on my face”.

A voyage through nostalgia, a quest for identity, belonging, an escape from something and a return, a desiring pursuit without end, a lust for life and ease into death; a twist of humour, a narrative of hope, aspiration and the failures that draw us back into the dustbowl. The American lyric is all of these things and more; its boundaries perhaps are pliable as the nylon strings on somebody’s battered acoustic guitar. Maybe it all culminates in madness and absurdity. For every One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, you’ve got The Felice Brothers’ ‘Jack at the Asylum’, a rollicking satire on the madness of contemporary American life which trades in richly surreal and absurd imagery to render the accelerated pace of this madness, crossing history in the blink of a screen flicker: “And I’ve seen your pastures of green / The crack whores, the wars on the silver screen”. Pastoral America is always already contaminated by an originary violence. Maybe the best American lyric depicts such realisations through personal stories, the relationships and encounters set against and embedded within wider structural phenomena, the recessions and closures and urbanisations. The Felice Brothers remind us, however, that all of this is secondhand, aspirational narratives passed down to us through screen culture, advertising: “You give me dreams to dream / Popcorn memories and love”. Once again, there’s that fluctuation between an earnest love of country to an embittered sense of its very elusiveness, the distant static shimmer of success whose failed pursuit we watch ourselves experience through the mediating comforts of daily life—the popcorn pharmakon poisons and cures for (post)modern existence, as calorific as they are nutritionally empty.

But once again, genre. String off a handful of names from Hart’s Americana playlist and you’ll be pressed to find anything that falls outside the folk-rock camp, even as its boundaries remain pretty permeable. Yet what of hiphop? Isn’t hiphop, in a sense, the great alternative American folk lyric? Rap is it’s own kind of poetry, after all. You might think of someone like Kendrick Lamar as an American lyric writer, working from a different generic background from Hart’s examples, but nonetheless telling the story of contemporary USA from the streets to the level of the visionary, just like Dylan did. Lamar even has a track called ‘Good Morning America’: “we dusted off pulled the bullet out our heads / Left a permanent scar, for the whole world to recognise / California, economics, pay your taxes bitch”. Once again, that originary violence, the scar of identity. Lamar works back from the wounding.

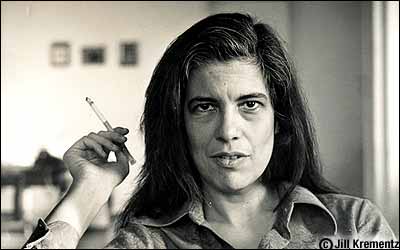

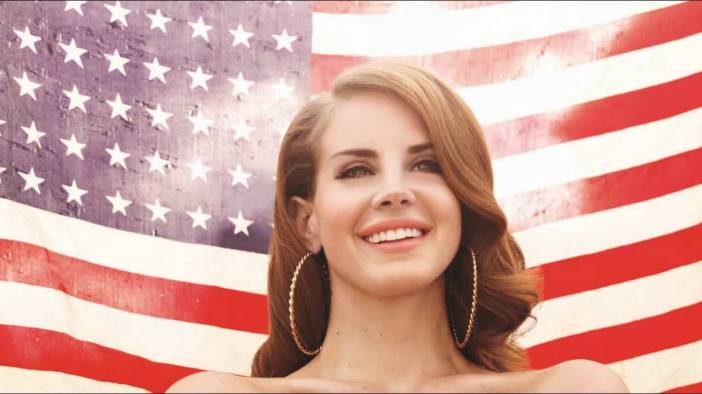

My knowledge of hiphop is far too limited to discuss it in any detail, but thinking it through the idea of American lyric prompted me onto the figure of Lana Del Rey, who often uses hiphop production techniques, from trap beats to muted, stadium echoes. I hate to bang on about oor Lana again (see articles here & here), but irresistibly she’s a shining example of a mercurial musician, drawn to the sweet dark chocolate centre of American melancholy. LDR performs a kaleidoscopic array of identities, just as Dylan often wore a mask that veiled itself in the confessional sincerity of the beaten-down worker, drinker, lover, escaping to the Mid-West alone. Yet while America’s great bard more or less got away with it, Lana has been constantly lambasted for her artifice and supposed inauthenticity. Which begs the question: what do we even mean by authenticity? Is only the white male—your Princes, Bowies and Eminems—allowed to strut in the performative identity parade? Both LDR and Lady Gaga have been lambasted for their supposed fakeness. There are obviously complex questions of racial, class and gender identity which I don’t have time to cover here. Sometimes, a musician is lauded for their alter ego (and doesn’t alter ego itself imply a certain surrender to the patriarchal ideology of masculinity?)—take Beyoncé’s hugely successful Sasha Fierce—and other times, it takes the invisible tide of the internet to swell in support for those critiqued by other forms of media.

My friend Louise is always comparing LDR’s work to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novelistic visions of 1920s America, and while this might seem a bit extravagant, there’s something to be said for the way Lana seamlessly evokes the spirit of the jazz age, the consumer paradise of the 1950s and the hipsterdom of millennial Brooklyn in the through the poetry of song. Is this just retroculture, in the sense of recycled kitsch and the twenty-first century urge towards nostalgia explored in Simon Reynolds’ excellent Retromania (2011)? Is there something pathological in Lana’s obsession with the past, a symptom of a broken psyche or worse, a broken generation? Perhaps. But there is something transformative and subversive about LDR’s retrovision, even as it may be critiqued for indulging in vintage gender roles as much as vintage styles (framing yourself as a sort of white-trash ‘gangster Nancy Sinatra’ is always gonna invite a certain feminist controversy, let’s face it).

One of Hart’s recent examples of the American lyric came from The National (even the band name evokes questions of what it means to be American), with their song ‘Sorrow’ from 2010’s dark and trembling High Violet. I’m interested in how this song apostrophises sorrow in the manner of a great Romantic lyric. We might think of Keats’ ‘Ode to Melancholy’ or Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets, the eighteenth-century cult of sensibility remade for jaded and alienated millennials. Sorrow once again invokes that Platonic idea of the pharmakon as both poison and cure. We can wallow passively in sorrow, as The National sing: “I live in a city sorrow built / It’s in my honey, it’s in my milk”: it’s a trapped landscape, a petrified terrain in which the self can only slip deeper into isolation; but it’s also milk and honey, a kind of temporary nourishment to a darker psychic scar. As Smith so eloquently puts it in the final lines of 1785’s ‘Sonnet Xxxii: To Melancholy’: O Melancholy!–such thy magic power, / That to the soul these dreams are often sweet, / And soothe the pensive visionary mind!’. Sorrow provides a toxic tonic for the soul, a lubricant for paralysis that eventually leads us back towards the existential road. Life goes on.

Lana Del Rey is fixated on sorrow. Blue, she admits, is her favourite colour, her favourite “tone of song”. Her songs are always hyper aware of the transient beauty of life, even as they lust after death. On the soundtrack song she did for Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby, she worries “Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?” ‘Video Games’ is a melancholy ballad for the contemporary relationship, a lush, brooding expression of love in the time of Call of Duty. Roddy Hart even did a cover of it. Her songs have titles like ‘The Blackest Day’, ‘Cruel World’, Sad Girl’, ‘West Coast’, ‘Old Money’, ‘American’, ‘Gods & Monsters’ and ‘Summertime Sadness’. All these titles evoke the Daisy Buchanan sad girl trope at the same time as gesturing towards the broader existential melancholy of America itself in the manner of Springsteen; with sometimes the detached urban cool of Lou Reed, other times the genuine, trembling passion of Billie Holiday. The video for ‘National Anthem’ restyles Lana as a Jackie O type married to a young, good-looking black president, with 1950s iconography spliced among pastel-hazed footage of the pair lolling around in love, sniffing roses, smiling, looking good as a Vanity Fair shoot. The video begins with her character singing Marilyn Monroe’s famous ‘Happy Birthday Mr President’ routine. She re-envisions JFK’s assassination, with a spoken word piece on top. She’s imagining alternative political futures even as she casts back to the past. There’s that lyric sense of wonder and ambiguity, of being lost in time.

It’s this layering of styles, scenes and cultural iconography that makes Lana’s work way more complex than most of what else fills the charts. Sure, it’s great that a positive message of bodily empowerment (Beyoncé feminism) is doing the rounds just now, but that shouldn’t mean that those who fall outside this category are anti-feminist or ignorant to gender identity politics. When all the R&B pop stars are prancing around proclaiming their sexual freedom, dominating men in various flavours of BDSM allusion, getting all the looks in the club or whatever, LDR is crying diamond dust tears into her Pepsi cola, draped naked in an American flag. Her videos, songs and artwork engage with cinematic discourse, high fashion photography and cultural history in a manner that’s intellectual interesting as much as it is affective and aesthetically satisfying. In a sense, she’s meaningfully evoking the past in order to say something timeless about the American dream and the objectified position of the ‘white trash’ woman under its mast of starry glory. In another sense, she’s indulging in a postmodern recycling of historical styles: constantly name-dropping, from James Dean to Springsteen, Lolita—perhaps the great American road novel not written by an American—and David Lynch’s lush, dark suburban epic, Blue Velvet. Despite the performance and ventriloquy of figures and archetypes from twentieth-century cultural history, she retains a sincere expression of melancholy, heartbreak and longing that’s personal but also strives towards rendering the more universal experiences of womanhood in certain communities. All the controversy surrounding Lana in relation to racial politics, class politics and sexual politics exists because her work is provocative, problematic and complex, like any good American lyric.

One reason that Roddy Hart was such a good choice to deliver this lecture is that he’s had experience writing new melodies for Robert Burns poems for Homecoming Scotland. Why is this relevant to the American lyric? So much of the lyric tradition, in all its forms, is based on that sense of romanticism, visionary wonder, self-exploration; the rendering of universal experience through personal narratives, the subjective telling of a story, the trade in imagery and sound and careful arrangement. Burns was a sort of rock star poet of his times, and not just because he was a bit of a cheeky philanderer. He toured around, worked as a labourer and farmer; he talked to many people, opened himself to influence. It’s this diversity that continues to mark the American lyric in the twenty-first century; the way that Father John Misty can sing a very ironic and playful song on late-show tv, about a man checking social media on his death bed, with the conviction of a crooning Leonard Cohen; accompanied by a gospel choir whose voice raises Misty’s ballad to a level of epic, overly extravagant grandeur that still somehow works, remains genuinely compelling beyond the initial sarcasm. The way Detroit’s angelic avant-indie hero, Sufjan Stevens, can ambitiously and patriotically plan to write an album for every state in America, then turn on the project, calling it “such a joke“. The way that Suzanne Vega, in ‘Tom’s Diner’, sings about a familiar American institution, the fabled diner—or Well-Lighted Place, as Hemingway put it—with the simple verse structure of an Imagist poem made narrative, sketching brief impressions of the myriad people she encounters in a public space. It feels cinematic, with deep eighties bass, bursts of brass and string-like synths, but also has that emergent sense of a postmodern folk, looking at the world from the bottom-up, catching everyday lives and stories in song. Even when irony remains the chief aesthetic order of the day, the lyric doesn’t have to be sucked into self-referential abyss. The best singer-songwriters continue to channel the American lineage through a romantic strain as much as a humorous one, inflecting songs with sorrow, joy and vitally that lust for something more—sometimes beyond life itself, sometimes just the restless possibilities of the road. Singing alone in the Glasgow Uni chapel on a Thursday evening, Roddy Hart rekindled some love for all that.

*

American Lyric playlist: