Category: ecology

Meadow portal

Visions & Feed preorder

£10.99

Coming December 2022 with HVTN Press

Visions & Feed is a collection that spans over two years of work brought together under the mirror phase of an anthropocene lyric filtered through crises of femininity, disordered eating, dysmorphia, labour and loss.

Sledmere asks: what does it mean to be a body in one of many dying worlds, what forms of work are done to endure it, what desires and pleasures are still possible and which are breaking down? Adopting playful and associative registers of ascent, while exploring devotion, metabolism, magic, domesticity and the ambience of dream forms, this is an intimate poetics of song and hormone, isolation and longing, fashion and pop, colour and vision in the saturated live feed of post-internet lyric. Amidst the reverb of climate melancholia and oestrogen blues, the speakers of Visions & Feed morph between depth and surface, film and music, myth and play to weather the days. Between epistolary, elegiac, confessional, ekphrastic, prose-poetic, processual, discursive and long-form cascades, the book offers iterative, experimental and fractal modes for exploring ecological entanglement within daily life.

♡

This is my second full-length collection, following 2021’s The Luna Erratum. Many of these poems were written during lockdown or in the stretch of long afternoons at the tail end of big critical work that had occupied me for several years. I was immersed in dream and the idea of symbolic disclosure in poetry, lyrical shatterings and seeing oneself forever through glass, never clearly. Through a glass redly, purply, wrong. It begins with an epigraph from Maggie O’Sullivan’s Palace of Reptiles (2003): ‘A glazier walks through the earth calling the ruins strapped / on his back an angel’. How can poetry fit ruins into any transcendent firmament when the shards are still stuck in its back? I was admiring the glazier from afar wanting him to fix me. Suzanna Slack writes in The Shedding (2022) of ‘trying to have angel surgery’. In this book, my speaker seems to want a stomach replaced by clouds and to rain forever, why is that? I was born in a lightning storm with a lilac tongue and ate the suns like smarties. Fine. Very mild, even warm. To become glint in general felicity. Giving a zoo charm. Zooming.

Infinity States: The Palace of Humming Trees

A few weekends ago marked a whole year since my exhibition with Jack O’Flynn, The Palace of Humming Trees, curated by Katie O’Grady. It was the height of summer, electrified by lightning storms and rain showers which sent the city streets flooding my ankle boots. I sat in the exhibition watching the auras of animals, drifting in and out of presence, doodling, planning short fiction I’d never write. The rain came down through the ceiling, just a little, and caught in a bucket. I texted in streams.

Something of the exhibition magicked itself into existence. We were all ’93 babies. Making things happen felt so easy. There were synchronicities and invincibilities. When Katie and I hung out at Phillies, we won the quiz. Jack and I wove this hyperplane of fantasy from the gestures of clay and line, whittling and glitter cast wide across floorboard and spiderweb. It was a strange time, the summer of 2021. I was also partially in the numb haze of grief. There was a delta wave but not like the deep sleep of the sea. People brought champagne and flowers to the opening. I wore a long white dress and wished the days were as long as they used to be. The Earth spins too fast.

Partly I wanted to write in the choral voice of many creatures speaking to one another. The process felt like a lyric surrender to this collective, their hyperintelligence of humming and stammer that spoke through pores, chitin, liquid. I don’t know where they learned all this. There was a sun virus in the emails we sent the summer before it. Time freckled on my arms. I could draw out the muscle ache from cycling more. It was possible then.

Anyway, about this experience of writing. A porous voice. Here’s an artist’s talk from a recent conference.

First delivered at Hear them speak: Voice in literature, culture, and the arts

10th June 2022

Who might be the ‘they’ in K Allado-McDowell’s statement? Taken from Pharmako-AI, published in 2021 and the first book to be co-authored with the neural network GPT-3, a system trained on extensive web data (from Google Books to Wikipedia), the quote suggests voice, presence and identity are questions of patterning, replication, weaving, plurality. Recurrent in Allado-McDowell’s book is the figure of the spider and its web, in a kind of constant movement like thought itself.

I was travelling north on a train when I began writing The Palace of Humming Trees, a book-length exhibition poem which forges energy fields of dreamy relation between many species of animal, mineral and element. Late spring and the fields I could forget about, texting myself more poem. The motion of the train according inverse to the downward scroll of the document. All the while seeing spiders in the corner of my vision, emitting great clots of silk. Commissioned by curator Katie O’Grady and made in collaboration with the artist Jack O’Flynn (both from Cork, Ireland), the exhibition was to offer something of a ‘hyperspace’ to its viewers: somewhere in which voices coalesced, formed new modalities of being and relation, new webs. In a Tank Magazine interview with K Allado-McDowell, Nora N. Khan notes that hyperspace ‘is an abstract space in which we perceive patterns of information and then shape them in language in order to communicate’. Having a big, serial and open field poem adjacent to visual work premised on bold, ecstatic colour and texture was to perform multiplicities of voice within an otherwise abstracted work. Inspired by Timothy Morton’s ideas of ‘dark ecology’, adrienne maree brown’s ‘pleasure activism’ and Ursula Le Guin’s ‘carrier bag theory of fiction’, I wanted to think about that communication as a form of attunement through which we gather, desire and coexist as ecological beings.

In The Palace of Humming Trees, the lyric voice is taken as that trembling spider silk assembling worlds. Spider silk is a protein fibre which embodies the inside of the spider woven on the outside for shelter, cocoon, courtship or the trapping of prey. It’s five times stronger than steel and is now being synthesised to make everything from body armour to surgical thread and parachutes. I began imagining the twangling of droplets on silk strands as the visualisation of a deep vibration, perhaps the wood wide web – something humming in and between trees. The world of the exhibition was inspired by the Irish folktale, The Hostel of the Rowan Trees, also known as Fairy Palace of the Quicken Trees. In the story, trees of scarlet fruit provide refuge, but the fruit itself (the quicken berries) are highly desirable to the point of despair. The rowan was brought from the land of promise, and its berries offer rejuvenation. With these symbolic undertones of danger and desire in mind, we wanted to explore a mythic ‘palace’ which merged the digitality of hyperspace with the organic textures of woodland and the chromatic intensity of dream, fantasy and ethical relation.

At the heart of our project was a notion of infinity. Hyperspace suggests that our ecological sense of world, surrounds, habitat, umwelt is always being reassembled. I wondered if infinity could somehow be voiced in a way that wasn’t just postmodern recursion or echo. What does it mean to be open to a state of infinity? To let many worlds pass through you all at once, making diamond-like instants and gossamer patterns of prosody?

Infinity became our figure for ambience. As spider silk is densely structured, and the neural net densely layered, so the notion of ambience captures, in Brian Eno’s words ‘many levels of listening attention’. To walk through the door of The Palace of Humming Trees was to enter a portal of multiplicity. You could take any route you liked around the room, moving between sculptures of hyperfoxes and sparklehorses, lichenous forms, ceramic butterflies of psychedelic hue and illustrated groves where trees shimmered green, orange, purple and blue. You could also scan a QR code and choose to listen to a recording of the poem, voiced by Jack, Katie and I and accompanied by Dalian Rynne’s sonic dreamscapes. To hear something ‘humming’ is to sense its presence, even if you can’t wholly understand it; humming implies electromagnetic vibration, birds and bees, a weather event or tectonic movement. We weren’t interested in translating the more-than-human voice so much as bringing it into the forcefield of lyric poetry, and through that expansive patterning achieve ‘infinity states’ of reassembled meaning, of felt experience that could not be crystallised into singularities of being. Visitors took pictures, sketched Jack’s sculptures, ran their fingers through the luminous plaster dust, placed to highlight the debris or excess of our clay animals. Something always in the process of creation or decay, incomplete. Corporeal, yet infinite.

One of the many voicings of this project was Letters from a Sun Virus, a correspondence between Jack and I that occurred over the first Covid lockdown, documented at the back of the exhibition book. While the email exchange had distinct senders and receivers, the you and I, over time in collaborating and sharing work between the visual and textual, our voices were beginning to mingle. Sometimes this co-voicing was painterly; other times musical, inflected with the characteristic intonation and energy of our respective speech patterns, moods, expressions. An entry from April 2020 reads: ‘…the wateriness of the poem. I had completely forgotten about all that blur. It’s like all the brush of the ocean and one which seems the idea to spill that way. Almost like a pressure, lines that go on and hair turning into the sea, each one of kinetic energy then finds all these points’. To assemble the correspondence for publication, I plugged it through text remixers, copying, pasting and rearranging phrases to enhance that sense of two voices repatterning one another. A ceaseless quest for points; for elements acting upon objects, emotions. Denise Riley has written of ‘inner speech’ as a strange oxymoron, where one hears voice at the moment of issuing voice inside us – a kind of running commentary that hums without actually humming. The letters suggest a kind of inner voice infected by the anticipated response of the other, rendering intimacies of collaboration which form a sticky substance, sentences and mobius formations holding time’s play and repeat – ‘Unending loop of my dream resins / not to complete the palace infinity of these trees’. Imagining the many of them speaking.

In Texts for Nothing, Samuel Beckett writes:

Whose voice, no one’s, there is no one, there’s a voice without a mouth, and somewhere a kind of hearing, something compelled to hear, and somewhere a hand, it calls that a hand, it wants to make a hand, or if not a hand something somewhere that can leave a trace, of what is made, of what is said, you can’t do with less, no, that’s romancing, more romancing, there is nothing but a voice murmuring a trace.

To ask whose voice in The Palace of Humming Trees is to hear sound bouncing as light, romancing, refracting in what Katie, the curator, calls a many-panelled ‘vivarium of humming thought’. To say ‘there is no one’ is to declare at once absence and the impossibility of presence as a singularity, there is no ONE. What if voice was infectious, modular, sporous, erotically charged, in common? Early in the project, I had this conversation with Jack where he told me that sometimes in the process of sculpture, he’ll try turning something upside down, or inside out, to revitalise the work. Make it strange or more-than. To sculpt by hand is to ‘leave a trace, of what is made’, and to write is to leave a trace ‘of what is said’. I wondered if the inner speech of the lyric ‘I’ could be turned inside out, to be exposed to the grain, the noise, the weather. A voice that touches is and is being touched, traced, smudged. I imagine this book as a glasshouse, somewhere between inside and outside, shelter and exposure; a chamber music of alchemical voicings, always repatterning, transforming each other. Sound and light. A place of invitation, ritual attention, metamorphosis. Many selves stuck to the web of a visual, expansive language.

Upcoming Workshops: Feb 2022

Experimenting with Weather

A workshop with me and Tawnya Selene Renelle

(Online and free)

Thursday February 17th

6-8:00pm (GMT) via Zoom

Join us for this free workshop. Maria Sledmere will be our guest as she gets you ready for her new course Writing the Everyday which will begin on February 24th.

We will be deep diving into all the ways we can experiment with weather and thinking about the ways that weather can shape both the content and structure of our writing. We will be thinking about the influence of weather and how something simple might be woven into experimental writing.

Suited to all genres, skill levels, and artists of any medium.

Register here.

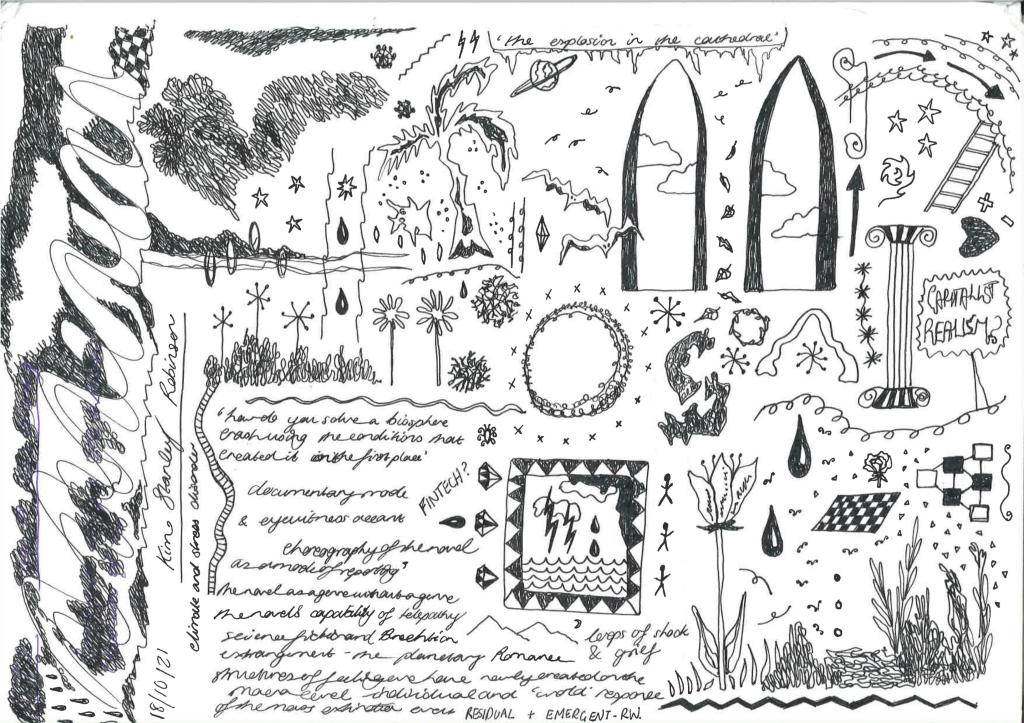

Ecopoetics and Postcapitalist Desire

As part of Glasgow Goes Green Festival (QMU, University of Glasgow)

(in-person, 5pm on 23rd February)

In his 2012 essay, ‘Post-Capitalist Desire’ Mark Fisher recalls protestors at the Occupy London Stock Exchange critiqued in the press for having iPhones and buying Starbucks coffee. In many mainstream framings of environmental activism, to be ecological is to be solemnly ‘pure’ and somehow entirely free of the taint of consumerism’s impulse. How do questions of energy, desire and expression come into artistic and activist responses to the climate crisis? Can we complicate the binary of ascetism and pleasure when it comes to ecology? This workshop asks: what does it mean to be ecological in and beyond capitalist society? Looking at various works of contemporary poetry, we will locate ecological thought within complex expressions of excess, hedonism and despair; works which intersect ecology with queer joy and critiques of racialised capital; works which negotiate ecological politics and ethics within everyday life and its games of recognition.

After a short introduction to ecopoetics, we’ll read some poems (distributed as pdf handouts), explore writing activities and have discussion.

Open to anyone interested in reading and writing poetry.

Location: this workshop will take place in Committee Room 1 of the QMU. Enter through the front door of the building and take the stairs or the lift ahead to the third floor. A member of staff will be present to direct you to the workshop.

Please bring your own preferred writing materials.

Register here.

Cowboy Gardening

It was supposed to snow in the night and the not snowing was sore as a missed period. I awoke with two crescent-shaped moons in the palm of my hand and thought of a sacrifice unwittingly given in dreamland. Said Jesus. Peridot phlegm and the scratchy sensation, knowing that speech too could be cool, historical, safe. Could not see beyond pellucid rivulets, Omicron my windows, my streaming January. January

streams from every well-known orifice of the world. Its colour is shamelessly stone. I seem to be allergic to inexplicable moments and so keep to the edge of the polyphony of yellow. I am cared for. The Great Barrier Reef dissolves in my dreams the substrate of yellow. It goes far. Pieces of the GBR are washed ashore in Ayr, Singapore, Los Angeles, Greenland. I go to these places by holding a polished boiled candy in my mouth, like the women in Céline and Julie Go Boating. My ankles licked by truest shores / but January didn’t fucking happen.

❤

Put together the orange-purple rose, your possible outcomes are red or gold (if you are lucky). Two reds together, with the golden watering can, could result in the rare blue rose. A novel rose. Black velvet roses grow in the old woman’s garden because she has infinite time to tend them. I’m not saying she’s immortal, like the Turritopsis dohrnii jellyfish; only that she doesn’t exist in our time. It’s rude to assume so. I’m not saying the lines of her face are asemic writing — nobody did that to her, or scarred her. She’s not scared. She just lives and dies all the time. She waters the roses.

Sometimes I imagine her in fisherman’s clothes, in meshy nightclub outfits of neon flavours, in extravagant ballgowns, blue boilersuits. Sometimes I’ve seen her before. The only way I can see her is to climb a few steps on the ladder by the village store, its red paint flaking, and I hang my body upside down the other side, risking exposure. I never eat before doing this. She doesn’t see me; she doesn’t see her roses either, not the blooms. In the village, people walk around with handfuls of rose seeds sometimes strung in little hemp bags. These are the currency of care. I have tended the young with haircuts and watched the flourishing of teenage roses. They say I am an old lady in the garb or garbage of former actresses. I hear them sing to me their stories. “Remember

she shot the guy who brought the astrograss”.

What they don’t remember, whippersnappers, is the incorrigible realism of that turf. Fuck it,

I have done nothing wrong. I perform for them my cowboy gardening. Broadcast the surplus value of our mutual twilight. Halloween roses for everyone. Every night I wake up from someone else’s childbirth and the world is so sore, the wound in the sky the snow wants to fall through. They bandaged it with realism. I need to go far. Do you remember the last time you awoke and felt like a person?

❤

The roses grow up in the gaps of the cattlegrid, knowing they will be trodden on. Again and again. We can’t stop them from doing this and they do it so often we have to account for a portion of Waste. Kissing you is itself a trellis. But we are propped and grown sideways with the vines strung betwixt our ribs. We are babies.

I like the tired way the roses intonate colour. The economics of the roses. Their euphemistic fetish. I tried to avow my commitment to rosehood the day I saw your calves all torn, and saw about women getting their labias reduced, and the red, blood roses sold on the internet, and rest. I lay this on your grave, the world.

My love, as a redness in our rosette

That’s newly worn in June

O my love, like the melt

That’s sweetly played in turbines

So fairway artery thou, my bonnie lasso

Defiled in love as I

Will love thee still, my decade

Tinged as the seas are garlanded dry

Tinged all the seas as thee, my decanter

At the romantic menagerie of sunset

I will luminary still, a debutante

Of the lighthouse sarcophagi

And plough thee well, my only lathe!

And plough thee well, awhile!

And I will come again, my love

Though it were ten thousand millennium.

My love’s rose-coloured highlighter really hurt the extra-textual, and thus booked trains to bed. I had an identity. I knew what you had done to the text. Austerity of the meadow to blame for ongoing culling of kin. You are abandonable as you have always been. Saplings for pronouns.

I feel wild and sad.

I feel pieces together stirring inside the world. Little bits of coral awake in

my throat, the shape of eight billion sun-spike proteins I was dumb

enough to swallow. It is not my fault but in my dreams

I get product emails like, Forget-me-not

a pair of jeans, high-waisted Levi’s

as if to wear at the end of the month

we keep saying sorry for delay, embroidered

our thighs with spiders

excuses to use lighters

without smoking

does it make us vectors

the warning of snow and ice still issued

from inside the snow globe of the rosehip

changes as it withers, glass shards

pissed from acid clouds in all colours:

black, blue, burgundy, cherry brandy, coral

cream, dark pink, green, lavender, light pink,

lilac, orange, peach, purple’s timeless red,

salmon, Hollywood white & yellow, rainbow

chosen for the significant other, a masculine flower

dipped in fortified light, I’m thankful

I look good lying down, the long unconditional stem

aka Lemonade, l-l-l-lemonade, l-l-l-lemonade…….

Particulate Matters

It was the morning I had decided to stop living as if dust wasn’t the primary community in which I sobbed and thrived, daily, towards dying. I spent Tuesday night in a frenzy trying to discern what particular dust or pollen (animal, vegetable, floral) had triggered my allergies anew, what baseline materiality had exploded in my small room its abysmal density. All recommended air filters had sold out online in the midst of other consumers’ presumably asthmatic dust panics; the highly desirable Vax filter seemed sold out across all channels, and I eyed up the pre-owneds of eBay with lust and suspicion, through a fug of beastly sneezes. A friend recommended the insufflation of water as a temporary remedy: ‘I drop some drops on my chopping board, get a straw and snort it up like a line of Colombian snow’, he texts me. I sneeze at the thought, but have to admit that the promise of clearing one’s nasal cavities with water is somewhat appealing. For isn’t water, like sneezing, a force in itself? Some kinds of sneeze come upon you as full-body seizures of will; so that to sneeze repeatedly you must surrender an hour or so, sometimes a full day, to the laconic state of being constantly taken over by this brute, unattractive rupture. ‘Sneezing’, writes Pascal, ‘takes up all the faculties of the soul’. My soul is in credit to the god dusts, who owe me good air. It’s why I am always writing poems (the word air meaning song/composition). But maybe I need good water, a wave of it.

In Syncope: The Philosophy of Rapture (1990), the philosopher Catherine Clément characterises sneezing as an instance of ‘syncope’: a kind of ‘“cerebral eclipse,” so similar to death that it is also called “apparent death”; it resembles its model so closely that there is a risk of never recovering from it’. My muscles ache; I eclipse myself with blood, cellular juices and water. What kind of spiritual exhaustion results from being cast into eclipse repeatedly? Quite simply, one becomes ghost: blocked, momentarily or otherwise, from the light of consciousness. One becomes lunar and attached to the dark bright burn, the trembling red of their inflammation. Those who suffer respiratory allergies might better glimpse what Eugene Thacker calls ‘a world-without-us’. I sneeze myself to extinction. It is the hyperbole of a felt oblivion. I do this on random days of the year, at random times; it is beyond my control. But can I derive pleasure from it, as one does the other varieties of syncope (orgasm, swoon or dance)?

Let me admit, I have always had a fetish for those moments on television and film where a character is administered, or self-administers, an intravenous dose of painkill so sweet as to enunciate this ecstasy simply by falling to a sweet slump, their eyes rolled back accordantly. The premise of silencing the body’s arousal so completely to blissful inertia (suspending the currency of insomnia, hyperactivity, anxiety and attention deficit) is delicious. The calmness of snowfall, as if to swallow the durée of its full soft melt. From quarantine, I fantasise about having adequate boiler pressure as to run a bath and practice the khoratic hold of hot water’s suspension. This is not what I text my landlord.

Recently, my partner spent several hours unpacking boxes from the attic of their parent’s house, in preparation for moving belongings to a new flat. The next day, I found myself suffused in the realm of allergy: unable to think clearly, or articulate more than three words without the domination of a sneeze. On such days, I am held on the tight leash of my own sensitivity: I tremble pathetically, my blood temperature rises; my nose glows reindeer and no amount of fresh air, hydration or sinus clearance will appease it. I am not ‘myself’. The body has enflamed itself upon contact with the ambient and barely visible. I feel an intimate, but non-consensual relation to the ghost trace, the dust trace, of all boxed things — finally been given the attention they so summoned or desired in dormancy. I mourn with objects the passage of time and neglect so betrayed on their surface; I never ask for this, but my body is summoned. Dust presses itself upon you, even as you produce it. I’m scared to touch things because of the dust. What is it but the atmospheric sloughing of something volatile, mortal — the grammatology of our darkest spoiler, telling the story of how bodies are not wholly our own, or forever.

Sneezing disrupts and spoils nice things; it is an allergic response to both luxury and decay. Cheap glitter, rose spores, Yves Saint Laurent. Sneeze sneeze. ‘When a student comes to class wearing perfume’, admits Dodie Bellamy, ‘my nose runs, my eyes tear, I start sneezing; there’s nowhere to move to and I don’t know what to do. When the sick rule the world perfume will be outlawed’. Often I have this reaction too. It prompts a fury in me: Why can’t I have nice things, as I used to? During my undergraduate finals, I developed phantosmia: a condition in which you smell odours that aren’t actually there (olfactory hallucination). Phantosmia is typically triggered by a head injury or upper respiratory infection, inflamed sinuses, temporal lobe seizures, brain tumours or Parkinson’s disease. Often I have tried to conjure some originary trauma which would explain my condition: did some cupboard door viciously slam my head at work (possibly), did I fall over drunk (hm), was I subject to some terrible chest infection or vehement hayfever (often)? Luckily, my phantosmia was a relatively benign and consistent scent: that of an ersatz, fruity perfume. It recalled the pink-tinted Poundland scents I selected as a twelve-year-old to vanquish the horror of body odour raised by the spectre of Physical Education, before graduating to the exotic spices of Charlie Red. I was visited by this scent during intervals of increasing frequency as I served customers at work, cooked or studied; I trained myself to ignore them by pinging a rubber band on my wrist, or plunging my nose into scented oils I kept on my person. Years later they returned at moments of stressful intensity; the same cryptic, sickly smell.

More recently, phantosmia, under the umbrella of a general ‘parosmia’ (abnormality in the sense of smell) is associated with Covid-19. Not long ago I realised I hadn’t been smelling properly for months, despite not testing positive until very recently. Had I, like many others, a ghost Covid that went undetected by symptom or test? Drifting around, deprived of olfactory sense, I felt solidarity with the masses of others in this flattened condition. I eat, but when was the last time I truly enjoyed food? My body doesn’t register hunger like other people’s; unless it is a ritualised mealtime summoned in company, I eat when I get a headache. Pacing around the flat, I plunge my nose again into jars of cinnamon, kimchi, mint tea bags, bulbs of garlic. Certain things cut through the fug: coffee, bleach, shit. I remember a friend, who was born without a sense of smell, telling me long ago that the absence of that sense made her a particularly spicy cook. Often she wouldn’t notice the over-firing of a chilli until her nose started running. What does scent protect us from? What does it proffer? Surely it is the unsung, primal gateway to corporeal desire itself: the gross and indescribable comfort of a lover’s sweaty t-shirt, the waft of woodsmoke from a nearby village, the coruscation of caramelised onion to whet your appetite. Scent is preliminary in the channel of want. Without it, I feel cast adrift into anhedonia. I begin chasing scent. Still, I sneeze.

Dust gathers. Is it yours or mine? Can we really, truly, smell our dust? How does dust manifest as material trace or evidence? In Sophie Collins’ poem ‘Bunny’, taken from the collection Who Is Mary Sue? (2018), the speaker interrogates an unknown woman on the subject of dust:

Where did the dust come from

and how much of it do you have?

When and where did you first notice

the dust? Why didn’t you act sooner?

Why don’t you show me a sample.

Why don’t you have a sample?

Why don’t you take some responsibility?

For yourself, the dust?

It would be perhaps an act of bad naturalisation to read the dust allegorically, or metonymically, as a figure for all kinds of evidence we are expected to produce as survivors of violence and harm. This evidence is to be quantified (‘how much’, ‘a sample’) and accounted for temporally in terms of cause, effect and responsible agency (‘first notice’, ‘act sooner’). The insistent repetition of dust produces a dust cloud: semantic saturation leaves us unable to discern the true ‘meaning’ of the dust. That anaphora of passive aggression, ‘Why don’t you’, coupled with the where, when and why of narrative, insists on a logical explanation for the dust that is apparently not possible. For anyone summoned to account for their trauma, the dust might be a sort of materialised psychic supplement: the particulate matters of cause and effect, unequally distributed and called for. It seems as though the speaker’s aggression, by negation wants to produce the dust while ardently disavowing the premise of its existence. The poem asks: is it possible to have authority over one’s experience when others require this authority to take the form of an account, a story, with appropriate physical corroboration? The more I read the poem, the more ‘dust’ becomes Covid. But it could be many things; dust always is.

‘Bunny’ also reveals the process by which testimony is absorbed into a kind of white noise, a dust storm repugnant to those called upon to listen. As Sara Ahmed puts it in Complaint! (2021), ‘To be heard as complaining is not to be heard. To hear someone as complaining is an effective way of dismissing someone’. Collins’ poem performs the long, grim thread of being told to ‘forget’, bundling us into a claustrophobia whose essence, the speaker implores, is ‘your own / sense of guilt’. Does this not violently imply (from the speaker’s perspective): as producers of dust, we take responsibility, wholly, for what happens to our bodies? I take each question of the poem as a sneeze: it is the only answer I have. I feel compelled to listen.

As she is asked, ‘Why don’t you take some responsibility? / For yourself, the dust?’, the addressee of the poem becomes conflated with the dust itself. I often think of this quote from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963), where erstwhile sweetheart Buddy Willard announces to budding poet Esther Greenwood, ‘a poem is […] A piece of dust’. Poems can be swept away; they are miniscule in the masculine programme of reality. They are stubborn, perhaps, but easily ignored by the strong and healthyy. In ‘Bunny’, the addressee’s own words are nothing but dust, ‘these words, Bunny’: the name ‘Bunny’ hailing something beyond the colloquial term, dust bunny — a ball of dust, fibre and fluff. The invocation of the name a kind of violent summons: you, the very named essence of you, are nothing but words and dust; there is no proof. The more I say the word ‘bunny’ aloud, the more I become aware of a warm and tender presence; this entity who has lived so long in the house of language — under the stairs, on the mantel’s sentence. Bunny, bunny, bunny. Clots in syntax. Dust can be obliquely revealed to all who notice; it coats the surface of everything. It is in the glow of wor(l)dly arrangement, the iterative and disavowed: a kind of ‘paralanguage’ Collins writes of in her nonfiction book small white monkeys (2017):

similar to ours but that is not ours […] when a writer manages — nearly, briefly — to access this paralanguage, we get a glimpse of what could be expressed if we were able to access this other, more frank (but likely bleak, likely barbaric) reality.

Running parallel to, or beneath ‘Bunny’, is the addressee’s reply, or lack of: the dust of her permeable silence, or inability to speak. It catches as a dust bunny in the throat. So how do we speak or listen, when faced with the aporetic knots of a hidden, ‘barbaric’ reality that is glimpsed in various forms of testimony and written expression? ‘Citation too can be hearing’, writes Ahmed. The title of Collins’ poem cites implicitly Selima Hill’s collection Bunny (2001), which she writes of extensively in small white monkeys as a book ‘I am in love with’. This citation opens ‘Bunny’ through a portal to the household of trauma that is Bunny: documenting, as Hill’s back cover describes, ‘the haunted house of adolescence’ where ‘Appearances are always deceptive’ and the speaker is harassed by a ‘predatory lodger’. Attention (and reading between texts) offers us openings, exits, corridors of empathy, solidarity and recognition. Its running in the duration of a poem or conversation might very well relate to the ‘paralanguage’ of which Collins speaks, in the oikos of trauma, grief and counsel. If poems are dust, then to know them — to write them, read them aloud and listen — is to disturb the order of things, one secret speck at a time. But the sight of each speck belies the plume of many.

The morning I tested positive for Covid on a lateral flow, having assumed my respiratory problems were accountable to generalised allergies, I decided to blitz my one-bedroom flat of dust. In the hot panic of realising my cells were now fighting a virus, I vacuumed my carpet and brushed orange cloths over bookshelves. I was really getting into it. Then my hoover began making a petulant, rasping noise. I turned off the power and flipped it upside down. To my horror, in the maw of the hoover’s rotating brush, I saw what can only be described as dust anacondas: huge strings of dense grey matter attached to endless, chunky threads of hair. Urgently donning a face mask, I began teasing these nasty snakes out with a pencil, as clumps of dust emitted from the teeth of the hoover and gathered on my carpet, thickly. All this time I was crying hysterically at the fact of my having Covid less than two weeks before my PhD thesis was due, the hot viral feeling in my head, and of having to deal with the dust of my own flesh prison: the embarrassment, shame and fail of it all, presented illustriously before me.

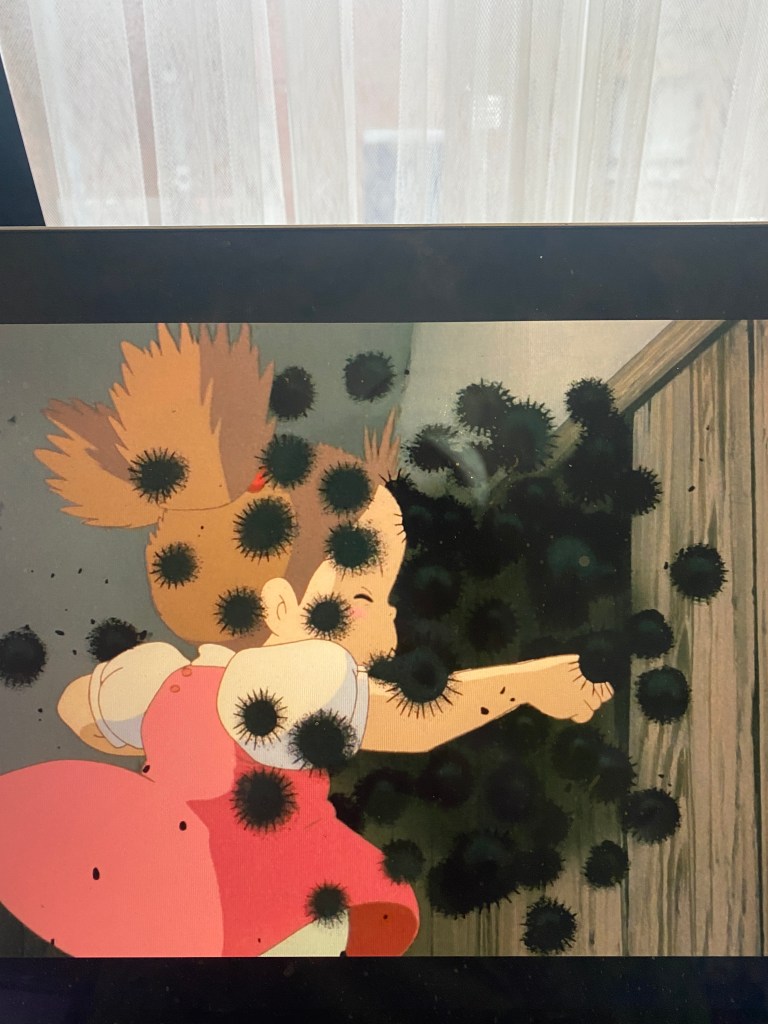

If only I could have purified my air! Forced to confront my body’s invasion (this time coronavirus, not just dust), I try to settle into the ‘load’. I make lists of the smells I miss, research perfumes online (aerosols glimpsed from the safe distance of text). I sneeze a lot, cry a lot, wheeze a lot; and then my sinuses go blank. Is this breathing? I imagine the cells of my body glowing new colours from the Omicron beasties. I re-watch one of my favourite Studio Ghibli movies, My Neighbour Totoro (1988), which features anthropomorphic dust bunnies known as susutarawi, or ‘soot sprites’ (which also appear in Spirited Away (2001)). The girls of Totoro, Noriko and Mei, initially encounter these adorable demon haecceities as ‘dust bunnies’, but later they are explained as ‘soot spreaders’ (as per Netflix’s Japanese-to-English translation). When the younger girl, Mei, gingerly prods her finger into a crack in the wall of the old house she has just moved into, a flurry of the creatures releases itself to the air. She catches one in her hands, and presents it proudly to Granny, a kind elderly neighbour who reassures her the soot sprites will leave if they find agreeable the new inhabitants of their house. When she opens her palms, the sprite is gone, leaving just a smudge.

An absent-presence in My Neighbour Totoro is Noriko and Mei’s mother, Yasuko, who is in hospital, recovering from an unexplained ‘illness in the chest’. Mei’s confrontation with the animated dust mites, or soot sprites, acts out the wound of her mother’s absence. With curiosity and panic, she and her sister delight in the particulate matters of the household, of more-than-human hospitality. What is abject about history then, or even the family, its hauntings, is evoked trans-corporeally through the trace materials of a powdery darkness, dark ecology (see Timothy Morton’s 2016 book of this name) that is spooky but sweet. (S)mothering in the multiple. My sense of smell now is consumed entirely by a kind of offbeat metallic ash; I’m nostalgic for cheap perfume. I’m not sure if this essay is a confession or who is speaking; it seems increasingly that I speak from a cloud of unknowing coronaviruses. And so where do I end or begin, hyperbolically, preparing my pen or straw? The ouroboros of my dust anacondas reminding me that I too was only here, alive and in this flat, by tenancy and to return from my current quarantine having prodded the household spirits for company, with nothing for show for it these days, except these, dust, my words.

2021 in review

From this year in-between brushing my teeth:

BOOKS AND PAMPHLETS

Miss Anthropocene (Mermaid Motel)

a selection of short lyric, ‘ethereal nu metal’ poems responding to the Elon Musk/Grimes complex.

Sonnets for Hooch – with Mau Baiocco and Kyle Lovell (Fathomsun Press)

An ongoing pamphlet series of sonnets attuned to the weirding seasons: what started as an internet joke about alcopops and longing as a keystone for exploring adolescent malaise, nostalgia and resilience thru civic space and Friendship. Current editions available are Lemon Bloom Season and Summertime Social. Two more instalments are forthcoming in association with Rat Press and Mermaid Motel.

Polychromatics (Legitimate Snack)

A pamphlet-length poem about colour, cetaceans and cosmic twilight, inspired by Walter Benjamin and a sculptural and textile works by the artist Anna Winberg.

Soft Friction – with Kirsty Dunlop (Mermaid Motel)

Soft Friction is an intimate gathering of dreams from 2018, written during a summer of ‘existential soup’, fainting at gigs, pulling all-nighters and panic surrealism. Extracted from a longer diary, these fragments wear the sensuality and sass of an active dream life shared between two people getting high on each others’ brains.

The Palace of Humming Trees (Sundays)

Edited and typeset by Katie O’Grady with visual identity by Paul Smith, this book-length poem features illustrations by Jack O’Flynn plus a curator’s word from Katie O’Grady and collaborative mixtapes. Set in the speculative locale of The Palace of Humming Trees, the poem is a jaunt through weird nature’s arc of glass, following the desire lines of hyperfoxes, sunburst melancholia and corona correspondence. Also available as a free pdf.

The Luna Erratum (Dostoyevsky Wannabe)

The Luna Erratum, Maria Sledmere’s debut poetry collection, roams between celestial and terrestrial realms where we find ourselves both the hunter and hunted, the wounded and wounding. Through elemental dream logics of colour, luminosity and lagging broadband, this is a post-internet poetics which swerves towards the ‘Other Side’: a vivid elsewhere of multispecies relation, of error and love, loss and nourishment.

ARTIST COLLABORATIONS

‘The Rosarium’ for Zoee’s album, Flaw Flower (Illegal Data)

A lyric sequence responding to the glistening pop garden of Zoee’s debut record Flaw Flower. Available as an A6 booklet as part of the limited edition album bundle.

The Palace of Humming Trees with Jack O’Flynn and Katie O’Grady (French Street Studios)

A collaborative project with artist Jack O’Flynn and curator Katie O’Grady which took place April to August 2021 and was showcased at French Street Studios in Glasgow. Featuring new works of poetry, sculpture, illustration and multisensory dreamscapes (from mixtapes to Tarot readings), we offered a ‘tenderly crumbling foliage’ of visual and sonic otherworlding.

The Dream Turbine with A+E Collective and The NewBridge Project

This online installation explores the relationship between sustainability and dreaming, offering a space to collectively share dreams and promote discussions surrounding these broader topics. The Dream Turbine was conceived by A+E Collective in collaboration with Niomi Fairweather and Jessica Bennett, as part of the Overmorrow Festival. I contributed to a preparatory DreamPak of resources and the curation of a Dream Vault and associated ‘Lost in the Dreamhouse’ workshop on Zoom.

Cauliflower Love Bike Episode 1: Play with A+E Collective

While play might be co-opted for capitalism, true play is that which exceeds instrumentalism and commodification. This episode reclaims play from its dialectical relation with work, exploring play as a practice and thought-mode that is capable of radical sensing, temporal sabotage, tenderness, sociality and a joyous excess that is also low-carbon. The podcast series was launched at COP26 in the Rachel Carson Centre’s pop-up exhibition at New Glasgow Society.

ACADEMIC ARTICLES

Article: ‘Hypercritique: A Sequence of Dreams for the Anthropocene’ in Coils of the Serpent Issue 8

An in-depth venturing through the possibilities of hypercritique, featuring readings of Billie Eilish, Sophia Al-Maria, Ariana Reines and more; plunging through dream, fire and the heartwood of anthropocene imaginaries.

“Just to distract you like the inside”: a correspondence wrapped up in Bernadette Mayer’s poetry, in post45, Bernadette Mayer cluster (with Colin Herd)

An epistolary collaboration which wraps and unwraps itself in and around the poetry of Bernadette Mayer, as part of a special cluster issue on Bernadette’s work.

‘I, Cloud: Staging Atmospheric Imaginaries in Anthropocene Lyric’, Moveable Type, Issue 13

Tracing the possibilities of ‘cloud writing’ in anthropocene lyric by way of Brian Eno, Mary Ruefle, Anna Gurton Wachter and more, asking what kinds of reading are possible or desirable in a medial world of thick atmospheres.

POEMS

- ‘It Isn’t the Mist’, part of special article ‘Why I Choose Poetry (What’s Nation Got to Do with It? What’s Gender Got to Do with It?): A Collective Poetry-Essay by 21 Poets Encountered in Scotland (2016–19)’, ed. by Jane Goldman, Contemporary Women’s Writing

- ‘Lower Your Cortex’, ‘Yesterday’, ‘Selected Ambien Worms’, ‘Aspartame Labour’, ‘Orchil’, ‘Olafur Eliasson’, in Litmus: the lichen issue

- ‘Am I to be nowhere, gently?’ in collaboration with Scott Morrison for SPAM Plaza

- ‘Ode to the Yamaha SPX90’, ‘Butterfly Pea Flowers, Light Years Away’ and ‘LA in November’ in THE MOON AND THE ECHO: responses to The Moon and The Melodies (1986) by Harold Budd and Cocteau Twins (Pilot Press, 2021)

- ‘Glitch Meridian’, ‘Small Deciduous Trees’ and three images in Tentacular issue 7

- ‘FOUR STRAWBERRIES ARE ALSO JEALOUS: A CASCADE’ in Virtual Oasis (Trickhouse Press)

- ‘Heaven’s Expense’, ‘Lark’ & ‘Nuptials’ in Hotel

- ‘from A Sun Journal‘ and ‘TEEN CANTEEN’ in Babel Tower Notice Board

- ‘Self Portrait at 27’ in MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture

- ‘But the Hard Glass’ + 3 images in ‘Blue and Green Project’

- ‘Lifestream’ in Scottish Poetry Library Poems of the Year 2020

- ‘When is the Best Time to Announce a Floral Pregnancy?’ in PROTOTYPE 3

- ‘Meadow Talk’, in MAGMA Anthropocene issue

- ‘Big Natural Course’, with fred spoliar, Babel Tower Notice Board

- Meadow Fractals for A Soft Landing

ESSAYS AND OTHER ERRATA

‘On Foam’ for Futch Press

Feature: Some Letters – a correspondence with Joe Luna

Review: Cloud Cover, by Greg Thomas

Feature: “It’s pretty utopian!” A conversation with Marie Buck, Mau Baiocco and Maria Sledmere pt.1, pt. 2

SPAM Cut: ‘I RESEARCH THE ORIGINS OF THE MODERN ROSE AND DISCOVER’ by Sarala Estruch

Feature: Some Notes on Muss Sill by Candace Hill

Feature: A conversation with Kinbrae and Clare Archibald ‘Tangents: letters on Etel Adnan’: a correspondence with Katy Lewis Hood in MAP Magazine (part 1) (part 2) (part 3)

‘‘Now now is everything’: Maria Sledmere on two maximalist poets of the Anthropocene’, Poetry London issue 99

‘Cloud Shifts’ BlueHouse Journal

Anam Creative Launch for MAP Magazine

DESIGN

Cover for Katy Lewis Hood’s Bugbear (Veer2)

Cover for fred spoliar’s With the Boys (SPAM Press)

Cover for SPAM Press Season 5 Pamphlet series

Playlist: October 2021

Wet-leaved, walking up hills with chain oil on my elbows, knuckles, knees. We are on the eve of the ‘big climate conference’, which is to say, to be a host city of preemptive closure: there will be no more roads so that nobody can block the roads without authority, no more bridges for your tiny feet. I imagine a commute that takes me north to Kirkintilloch and back along the canal, an extra hour and a half of leg power and stamina and to arrive like of a beetroot complexion to the moment when somebody speaks. These streets are mostly broken glassed, and I see nothing to sweep that; I see buildings go up, see extravagant plant life grow from abandoned houses. I dream about bike punctures from enormous shards of glass. A mushroom sprouts in the brutalist building. I should have planned to do something. More tired than words can.

Imagine awaking beautifully at 5am each day, to actual birdsong and car sounds, still going through the night to Edinburgh or the general east as they do. I miss the ocean, which I have not seen since May. Sometimes I forget that its quiet, rhythmic hush is always in my ears, a tinnitus with the switcher dimmed. All summer I swapped the ocean for industrial estates, teeming with buddleia. If I go to a club, it gets full bright. The hush. At 6am I make atomic coffee, await words, say rain. I could tell you about the new university building and how I will never find a space to work there, doomed to circle identikit floors like airports in a suspended time that nonetheless eats into my time of work, a starship, doomed to fill a cup of hot water and carry it up and down escalators only to be cast back outside with scalded hands, cried into blustering autumn. A hazmat suit to be a student, studying the microparticles of your love in blunder. If I could study on the floor, in the street, with the leaves stuck to me. But I am a sufferer of frostbite and poor circulation, owing to damp homes, an unfortunate experience in the snow and damaged nerves, fragile metabolism. I am not there anymore, in the place we have been

Canned words taste better with more salt on them. Fuck you. Sitting on the curb in the 1990s surprised us when a plane went by, it was carrying my childhood. Remember we used to put each other literally in bins, until that wasp stung your ass and I was sorry. We prise open tins for the juicy bits of the story like, what would it take to get the attention of a virulent benefactor? Should you become a red squirrel enthusiast, or take up the statuesque hobbies of sportsmen? What beneficent largesse would require it?

Imagine not living by the anticipatory hormone storm of a coming menstruation, or like, the cramping wildness of the night and morning or blood gushed trying to have coherent thought in the day when your mind is fog. I want to transcribe some of that fog to writing, to remember how it was when again I am in clearing, to be like this is the place, it’s never gone. I was held in it, the tearing itself to shreds sensation to write this at six in the morning before work. Plants don’t have to go through this; is it that they’re always ‘working’? How do trees feel when they shed their leaves? Is it like an annual period and do they miss them? Should I develop fondness for shreds of blood in the toilet, abject bits of me and not? I saw a leaf blush out of my mouth and into a leaflet. Smoking kills. I watch the men in high-vis sweep up the dead leaves, more like dying, into black bags by the side of the road. Someone around here is always burning rubber tyres in secret. It’s kind of erotic to watch people do something repetitive and with great concentration, as if no one else could possibly notice this. To do your work that way. O your beautiful butterfly shoulders. Missed opportunities.

For instance, I could have lived through this moment to learn another language, write a curriculum vitae for the purposes of waged employment, called you.

“It feels so good to walk in nature.”

Blood drop in the shape of sycamore.

Where is Canada?

The revenge fantasy is only that trees are flirtatious as hell, winking pollen so that you watery-eyed have to look up at the stars sometimes and beg, like take me. Let me out of the forest so I might see

(fantasies of committee,

the ground to tie

my own laces in figures of eights.)

Authenticity!

The figure of eight in Karla Black’s sculpture which is pink-smeared recalling everything I used to put on my face. The idea is to find a sort of peace with it. School bathrooms where a face was pressed against glass and cruelly examined. I dream of rooms filled entirely with blizzards of eighties-blue eyeshadow. Angel Olsen, 2014, Pitchfork Festival. Having lived with the spirit not for resale, traded on a stark memory of that colour where every remembrance seems to intensify blue, until all I have is the pigment itself, ultramarined into oblivion. To wake into that blue and not see beyond it. I put my sore arm through the right-hand loop of the eight and pulled this out for you.

In the dream we pass an armed convoy and into the bakery with coins allotted to us by authority figures, and we buy pastries adorned by sugar ice drawn in mobius curlicues, and the pastries flake away as we eat them, greedily on the street, so many flakes falling before the guards. And we are butter-mouthed in the face of conflict, war and summit. A kind of shout chokes the air but the golden morning goes on, the falling leaves. I have these cramps and double over in the falling leaves. Men come to sweep around me, where I have fallen. One of them bends down — he is so young to be working — and pats my head tenderly and I see a leaf fall behind him and I know that leaf to be us, so we embrace platonically for one moment, as though I were his long-lost twin, before the foreman calls his name, which I can’t recall—

No, not that at all — he touches the soft part of my ear, goes “are you not young to be leaving?”

In trash, the language of trash, the trash piled up against the highway of your declaration. The men stopped coming.

Azalea, camilla, plum blossom, hydrangea.

Rizla, tin foil, styrofoam, gum.

The noise of vehicles pulling up around the city, emitting fumes.

The petals shed and I sleep on them, dreaming my blue becomes turquoise

another morning where the sun won’t rise

until we are paid.

~

Painted Shrines, Woods – Gone

Au Revoir Simone – Stay Golden

Uffie – Cool

Margo Guryan – Something’s Wrong with the Morning

Green-House – Soft Meadow

Frankie Cosmos – Slide

Arthur Russell – A Little Lost

Grizzly Bear – Deep Sea Diver

Tricky – Makes Me Wanna Die

The Raveonettes – I Wanna Be Adored

Beach Fossils – Sleep Apnea

Lykke Li – I Never Learn

Cate Le Bon – Running Away

Vagabon, Courtney Barnett – Reason to Believe

Angel Olsen – Some things cosmic

Jason Molina – I’ll Be Here in the Morning

Cat Power – I Found A Reason